Return to “We Saved the Day”—the WWI Letters of William B. Moore, 6th Marine Regiment, 2nd Division, American Expeditionary Forces.

Letter 24

[Woëvre Sector, France]

May 1st, 1918

Dearest Mama,

Just a few lines tonight to let you know that I have returned from the school to my company. They are near the place where they were when I left to go to the school and very shortly I am going back into the front line again—not the same place as I was before however. I didn’t appreciate what a comparatively soft time I had at school until the last few days after my return. I have been working very hard and I hope to get a rest in the front line if the Boche will let me.

A lot happened to my battalion while I was away. One of the officers received the Croix de Guerre for killing about 43 Germans in a raid and my own platoon met with some gas which caused no deaths fortunately. I’m sorry I missed all the excitement but we’re apt to have more before we leave. Don’t let all the talk worry you for there are no heavy operations where I am and I’m not worrying myself so I hope you won’t.

Some letters from you and sister were here when I returned, dated the latter part of March…

May is upon us but still it rains and the sun hides his face. I have high hopes for better weather someday soon, and the sooner the better for everybody. I have yet to convince myself of the authenticity of the name “Sunny” France. I have not been able to get in touch with the paymaster to extend my allotment so after the sixth, there might be a lapse of a month but i fully intend to do it. I’m sorry I wrote you so optimistically about being sent home as an instructor. There doesn’t seem to be much chance at present but there’s no telling what might turn up…

Bushels of love and thoughts always. Your devoted son, — Billy

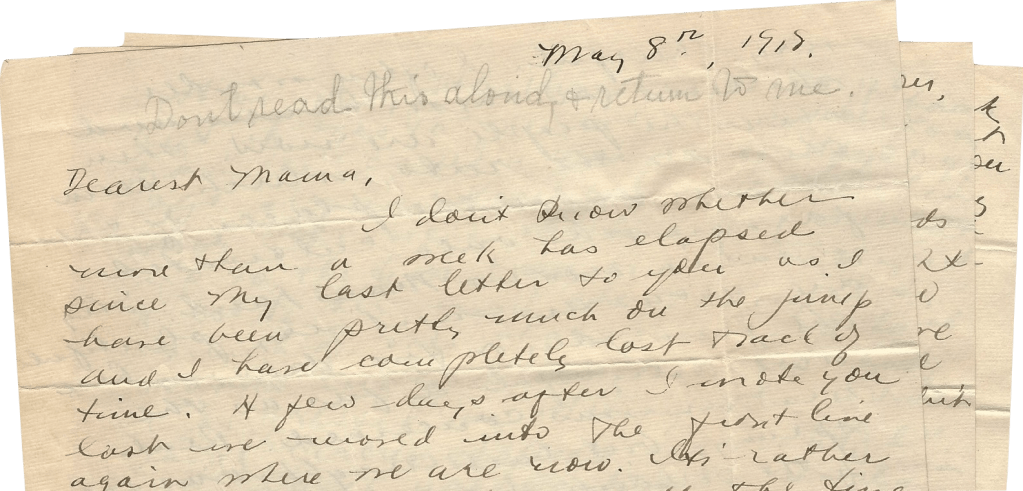

Letter 25

[Woëvre Sector, France]

May 8th, 1917

Dearest Mama,

I don’t know whether more than a week has elapsed since my last letter to you as I have been pretty much on the jump and I have completely lost track of time. A few days after I wrote you last we moved into the front line again where we are now. It’s rather quiet but I am busy all the time and one day is just the same as another. That expression “carry on” certainly applies perfectly to our existence here in this particular place—and since I have been here I have wondered more than ever how much more carrying on we’ll all have to do.

I am in a little town which has been completely demolished and it’s all so typical of the nature of the war and the ruined houses are all I see all day that the aspect isn’t very cheerful. I often wonder who lived in these houses and where the people are now. Then there are the rats which seem to have taken the place of the farmers who once cultivated what is no no man’s land. They are monsters and very plentiful. The first four or five days in here were delightful as far as the weather was concerned. Real spring. But last night was one of the wildest I have seen. A deadly calm punctuated by immense flashes of lightning and then the rain came with inky blackness. I sat in an observation post for four hours waiting for the flashes of lightning to illumine no man’s land so that I could see what was out there. Not even a German would have thought of stirring out on a night like that, but our vigil never ceases—just carrying on.

I must tell you something. Jean Hill is married, which may not be very startling news to you, but it was to me when a letter from her came a couple of days ago acquainting me with the fact. We were the best of friends up to the time I sailed; I thought a lot of her and she thought so much of me that we might have become engaged before I left had I pressed my willingness. I didn’t think circumstances warranted it, which judgment was more from the head than the heart because I was just about pretty sure I loved her. I wouldn’t have sprung it as a surprise on the family and the reason I never mentioned it to you was because I had no intention of becoming engaged before I left, However, after I got over here things changed a bit. It was the old adage of “absence makes the heart grow fonder,” I suppose, and I really felt that I couldn’t care for any other girl. I wrote and told her and we sort of mutually agreed that she should wait for me and the future would take care of itself.

As you know, she and her mother have been very good to me and I know her mother very strongly approved of me. When I got back, I was going to have you meet her and that’s all there was to it. That’s the way matters stood when I got her letter saying that she had married this other man after having spent much time in deciding, etc. Her letter was very clear and fair and I have nothing to regret. It was just the natural course of events and in some respects is probably just as well. There was never anything wrong with our friendship and we both feel that it still exists. The love part of it ended just as naturally as it came, only I was over here in France with no immediate prospects of returning and her husband, who is a Captain and was at Yaphank [New York] and was just about to sail, so without my going into details, I think you can see just how the whole thing was. It was so unexpected that it came as a blow at first but it has by no means upset my equilibrium and you are still my real sweetheart.

Now this is one letter which I don’t want passed around outside of 617. You all will have a good laugh, I know. I don’t mind that, for a good laugh in these times is worth money and I don’t mind if it is at my expense. However, all such fanciful thoughts are out of my head now, you may be sure. My mind is set on the task in front of me which is to do my share toward ending this war even though it should end me. That is for Him to decide and that satisfied me.

We might have our chance soon to fight with the British. There are rumors in the air and it seems certain that we are not to stay in here as long as contemplated at first. It is my earnest desire that we move and I’m hoping for it…

I am getting along fine so there’s no cause for anxiety. All my love and prayers for all. Devoted, — Billy

Letter 26

May 23rd, 1918

Dearest Mama,

It has been two weeks and over since I wrote you last—the longest interval between letters since I have been in France, I believe, but we have been moving and that accounts for it. Just before we start a movement, our regimental post office closes and remains closed until we strike our next destination and as this latest move was of two weeks duration, I couldn’t send a letter out even though I had time to write on one or two occasions.

In all, my regiment spent two months at the front. One I spent at the school of which I have written you and the other I spent right in the front line two weeks before going to school and two weeks after my return. Then we moved out and for two weeks we have been traveling. They have been full of interest and the sum total amounts to one of the greatest experiences I have had so far. I wish I could tell you every little detail and give you all my impressions but I shall have to omit some.

From the trenches my company moved back to a town somewhere well behind the lines. The French relieved us and I was left behind for 24 hours with them, according to trench etiquette to explain and answer any questions which might come up about that particular part of the line. This particular regiment had come up from the Somme and during my stay with them, the officers told me many very interesting things about the German drive and the fighting they had been in. My knowledge of French is gradually increasing and although at times I have difficulty in making myself understood, I can usually catch what they say. The officers that I met of the regiment that relieved us were very keen for the Americans and they certainly showed it by their hospitality and concentrated efforts to please me while I stayed with them.

One thing that struck me particularly was the fact that they like the Americans far greater than they do the British, not as soldiers necessarily as we really haven’t had the chance to show what we’re worth as yet, but rather as personalities. In fact, during the past two weeks of travel, I have learned that from the civil population, and they like the French soldiers, have given us the impression that in America lies their one great hope—and they are willing to do anything to show their appreciation.

When I was at liberty to leave the trenches, I proceeded over land by automobile to the town where my company was billeted. It was a beautiful spring day—everything was green and the fruit trees were in blossom. Coming as I did out of our little town of devastation in the front line, the country looked all the more beautiful. Everywhere the fields showed cultivation and I realized once again why the motto of the French army at Verdun was, “they shall not pass,” and what a privilege it was for us Americans to throw all our strength and resources to the aid of France and the common cause.

I reached my destination late in the afternoon, found my billet and washed the dust off me. The next day was my birthday and by way of increasing my thoughts of home, a letter from you reached me. Just as I was about to sit down and write, I got word that the company was to move again early the next morning so I had to turn and pack up again. I managed to celebrate the day by arranging a special dinner for our company officer’s mess which was quite a success.

We moved early the next morning and marched thirteen miles. It was a beautiful day and the scenery was magnificent but the sun beat down upon us with fury and the men in their heavy marching order suffered quite a bit but only a few were compelled to drop out. Our destination was a small town near a small-sized city. Here my company was billeted for three days and our job was to load trains which were taking American troops to other points. The country thereabouts was the scene of one portion of the Battle of the Marne and quite frequently we could see along the roads a wooden cross enclosed by a small fence with the simple marking, “X Soldats Allemand” (10 German soldiers). The town we were billeted in was occupied for a period of three months by German troops in September 1914.

From that town we took a twelve hour train ride through still more beautiful country. At one time we were in sight of Paris. The spires of Montmartre could be plainly seen and even the Eiffel Tower was visible in the distance. Everywhere we went the people cheered us and the memory of one old man in particular shall remain with me. Our train consisted of some 50 off cars and the officers coach was in front. We passed near an old farm house with an old man plowing nearby. As the train passed by, he stood up and taking his hat off, held it high above his head. I leaned out the window and watched him and he stood in that same position until the entire train had passed before he put his hat back on and resumed his work. Too old to fight, yet he was tilling the soil and still had enough of the soldier in him to render a salute to a train load of Americans as they passed.

We detrained about 9:30 that night and marched a couple of miles to a town where we were billeted. My room was in the Mayor’s house and needless to say after a long train ride and a hike, I lost no time in getting to sleep. The Mayor’s son, a man of about 30, was an artist. He had lost a leg early in the war and is now devoting himself to war paintings, some of which he showed me. They were remarkable. One of the ones he showed me was a painting of Ypres from Mount Kemmel before the Germans took it. He sends them to the National Museum in Paris and no doubt received a tidy sum for them.

The next morning we moved out at six o’clock and covered about ten miles when we halted for lunch. It was hot going and everybody was pretty much all in. After a much needed three hours rest we proceeded to a fair sized town whose name, singular enough, is identical with that of our corps where we were billeted for the night. Here I had a room in a very nice old house with a beautiful garden. The furniture was old and priceless and the house was literally filled with antiques. It was an education. The only inhabitants were a very old lady, her maid, a little French girl who looked like a doll, and a boy of 15—a Belgium refugee. The old lady treated me with motherly affection and when I blew in all hot and dusty. gave me an enormous bowl of milk—the first I had had in months. The three of them sat down with me and assured me that they were glad to see all the Americans as we had come to save France from the Germans.

Our dinner that night was arranged by our interpreter in advance and was one of the best I ever sat down to. The room in which our table was set looked out into a beautiful garden and along with the meal, I had the pleasure of seeing the sun set behind the hedges of rose bushes. The table was decorated with American, French, and Belgium flags and during the meal the little boy of the house came in and handed a card to my captain which read, “In the name of my father who was killed in the war, we welcome you to this house, and join together in hoping for a victorious peace and glory to France and America. The youngster saluted and said, “Vive la Amerique” which he had evidently practiced beforehand.

We hiked again yesterday about twelve miles in all, and reached this town about 3 p.m. where we are to stay in the time being. There is no other way to describe the hiking we have done than grueling. For the past two weeks the weather has been fine but too hot for comfort on long marches. The experience though has been wonderful and well worth while. It has been sort of a tour and has brought us to still another part of France. Not many Americans have ever been along this way so you can imagine the warmth with which these people have received us in their homes. M any a time within the last six months have I felt considerable satisfaction in knowing that I was with the first Americans to do this or that. Although you didn’t raise your boy to be a soldier, somehow or other he got here among the first.

Just how long we are to remain in this place, I can’t say. We shall resume training and drilling and then no doubt return to the front to take a more active part than we have heretofore. No doubt the Marines will take part in the fighting on the Somme. That seems to be where we’re headed for. Here again we will be among the first.

I am wearing my service chevron now, representing six months service in France. The regulations call for placing it on the sleeve so that many more can’t be gotten underneath it. That might be taken as an optimistic sign…

Well, Mrs. Moore, you’ll soon have to be addressing your son as Captain Moore as it’s only a matter of a month about before I’ll get my commission as such, my promotion having been assured by the increase in the Corps to 74,000. That will mean all sorts of changes and I can’t tell what will happen to me. Two more regiments of Marines are coming over soon and that will give us a division in France. I can hardly believe that I’m going to be a Captain but it’s evidently certain. Looking at it unsentimentally, it will mean $2400 a year for me with some back pay…

I am well and happy and I hope everybody at home is the same. When we came out of the trenches we decided we would live high for a while and whenever we stopped we got the best food money could buy and I have had some wonderful meals prepared as only the French can prepare them.

Even with all the hiking, I don’t think I have lost any weight but the most important thing is that my spirits are 100% perfect, for six months over here has taught me that health without morale is wasted.

Lots of love to all the family and bushels for your own self. Your devoted son, — Billy

Letter 27

May 30th 1918

Dearest Mama,

Today is Decoration Day and as it is a holiday for the A. E. F., I find myself able to write again after a busy week’s interval. I wrote you in my last letter of having traveled far and hard and having temporarily at least halted to rest up. Well, we move again tomorrow and I will say that our sojourn in this particular area has benefitted everybody. The weather has been superb and just to be able to get out into the open and exercise has made the men straighten up and get rid of the kinks acquired by living in dugouts and hiking day after day with heavy packs on.

Since we have been here, I have received several letters from you…Most of them reached me in three weeks time and less. The mail services seems to be improving greatly, both coming and going, and it’s to be hoped that the good work continues….You can’t imagine how delightfully surprised I was when I found those pictures of you all in with the handkerchiefs. My eyes just feasted on them and I have looked on them many a time since with mingled feelings of homesickness, pride, joy, and sorrow. To see you and Papa sitting on the steps of 617 brought me nearer home than I have been since October 30th last although there have been other times I have been entirely absent from France. Those pictures shall be with me at all times and will refresh me instead of too much of France’s water on these long hot marches.

As you can judge, we are not at the front now. This is our breathing spell, so to speak, before we go in again. We are headed for some part of the present battle but I don’t know just where and I’m sure when the Marines get there, they’ll give a good account of themselves. Your guess as to my previous whereabouts at the front was wrong. I was near Verdun and the Marines were the first Americans in that sector when we took over the trenches, My platoon went right into the front line and i figured it was just about the first platoon in. I was on the extreme flank of my division nearest Verdun. All of those little points being singularly mine, and i take pride in telling of them. When I was away at school. it was behind the lines that Bill Osborne and my platoon got gassed. They were subjected to very heavy bombardment of gas and high explosive shells and it was only through some keen foresight of Bill’s that a good many weren’t killed. As it was, some of them took off their masks too soon after the bombardment and suffered the effects of mustard gas. Bill got it only very slightly and none of the men was completely put out of commission although a few are not quite well yet. Soon after we left the front, Bill was transferred to an Army infantry regiment and I haven’t seen him since.

Well, I am no longer with the 97th Company. I mean that at present I am on detached duty that may or may not be permanent. I don’t know yet. I have been made Regimental Liaison Officer—“liaison” being the French word of communication. It means that when my division is at the front, I am attached to Brigade Headquarters to see that communications are constantly maintained with the regiment, that I live with the General and his staff, and that I am in a position to know pretty much of everything that goes on and that in case of action, either defensive or offensive, a whole lot depends on me. What will interest you mostly though is the fact that at the front, Brigade or Divisional Headquarters are not located in the front line, [but] somewhere behind, and that living with a general is a little pleasanter than living in a rat-infested dugout, or no dugout at all.

When I was first assigned to the job, it was with the understanding that I was to hold it only until another officer should return from school. That wasn’t so very satisfactory, but I decided I would make good as long as I had it and I just learned today that the job is permanently mine if I want it. Whether that’s the result of the work I have done already, I don’t know, but I am pretty sure I have accomplished a little more than they expected in the short time that I have had the job. The officer who has the same job in the 5th Marines is a Captain and I don’t think he was very pleased at first when he learned that in the 6th, it was handled by a 2nd Lieutenant. I haven’t yet decided whether I want to stay with it or not. I have been with the 97th Company all but three weeks of my ten months in the service and I hate to leave them…

I’m sorry I spoke so optimistically of my returning home but I warned you not to be disappointed. An instructor’s job is nice, no doubt, but don’t think, Mother dear, than any man is too good to fight. It’s his first duty and maybe that’s why they’re keeping all the Marines right here and sending more over besides.

Must close now and get this in before the post office closes. Will write again at our next stop. Bushels of love for all at home and more than that for yourself. Your devoted son, — Billy

P. S. June 5th. Just about two hours after I wrote this we got orders to move and I have carried this around since. I am sending this back by an officer who is returning to the States. The German drive became so serious that my division was rushed up to help stem the tide. We traveled for 48 hours without stop and went right into it and stopped the Boche as you have probably read in the papers. The Marines did it. We are now near Chateau Thierry. I am with Brigade Headquarters as I explained in the letter and in very little danger although I’m ashamed to admit it. We have stopped the advance and everywhere the French sound our praise. Gen. Pershing was here yesterday and couldn’t say enough for the Marines. Everything is very exciting with much [ ] activity and wounded prisoners being brought in. One had a French uniform on. The situation is very favorable and I shall write you more at the first opportunity. I am well and happy so don’t worry. — Billy

Letter 28

June 11th 1918

Dearest Mama,

I had planned to write to you yesterday but was prevented from doing so by being called out at 2:30 p.m. and I was out all day. Was do tired last night that I availed myself of an opportunity (which are scarce) to sleep, and so another day slipped by. I haven’t been able to write as much as I wanted to for as you know we have been in the thick of it and I’ve hardly had time to sleep or eat.

Received some mail today—the first in a couple of weeks. Your card written on my birthday [came with other mail]… I have been able to send out two letters to you within the last ten days, both by officers returning to the States… One letter was written back of the lines just before we moved up but I never had a chance to mail it. Things have been hopping so I shall start this from where I left off in my last letter.

For about ten days before the end of May, we were back of the lines and reorganizing. headed as we all knew toward the Somme battle front. The time was set to move but all of a sudden word came from somebody and ten hours before the scheduled time we were loaded in French trucks and hustled off in a different direction, back to the one which had originally been contemplated. We were on the trucks for twenty hours. It was the dirtiest, roughest ride I ever hope to take. We left the trucks, rested in a town for about ten hours, and then marched right up to meet the oncoming Germans. We took our positions the night of the 1st of June and since then the Marines have been fighting almost continuously.

We went right in to meet them at the farthest point of their advance—the closest point to Paris, just north of Château-Thierry. The French were retiring before the tremendous onslaught but the Marines held and when the Boche was stopped, pushed him back about two kilometers in the direction when he had come. That’s what we have done in the last ten days and I’m wondering just how much of it you have read in the papers. It has appeared in the papers over here so by now you have probably read all about it.

It has been magnificent and of course this past week and a half with its fighting, its scenes, and its sensations, I shall never for get. We paid dearly for our success, but every life, every wound has not been in vain. In the first place, we saved the day, That’s the only way to express it. Some day I hope to be able to tell you the condition of things when we first got here. The men who died here died for France and they went into the fight tired in the beginning from their long hard journey, but eagerly and willingly.

In the second place, there’s no doubt in anybody’s mind that we can lick the Boche. In fact, we have been doing it and the prisoners we have taken admit it. Whereas before the Boche has struck awe into the hearts of men, now the name only excites contempt. The Marines, anyway, have gained confidence by their successes and no doubt that confidence has spread to America. I have every reason to believe that there are now nearly a million of our troops in France and although they might not be quite as good as the Marines, I’m sure they can give the Boche a good licking.

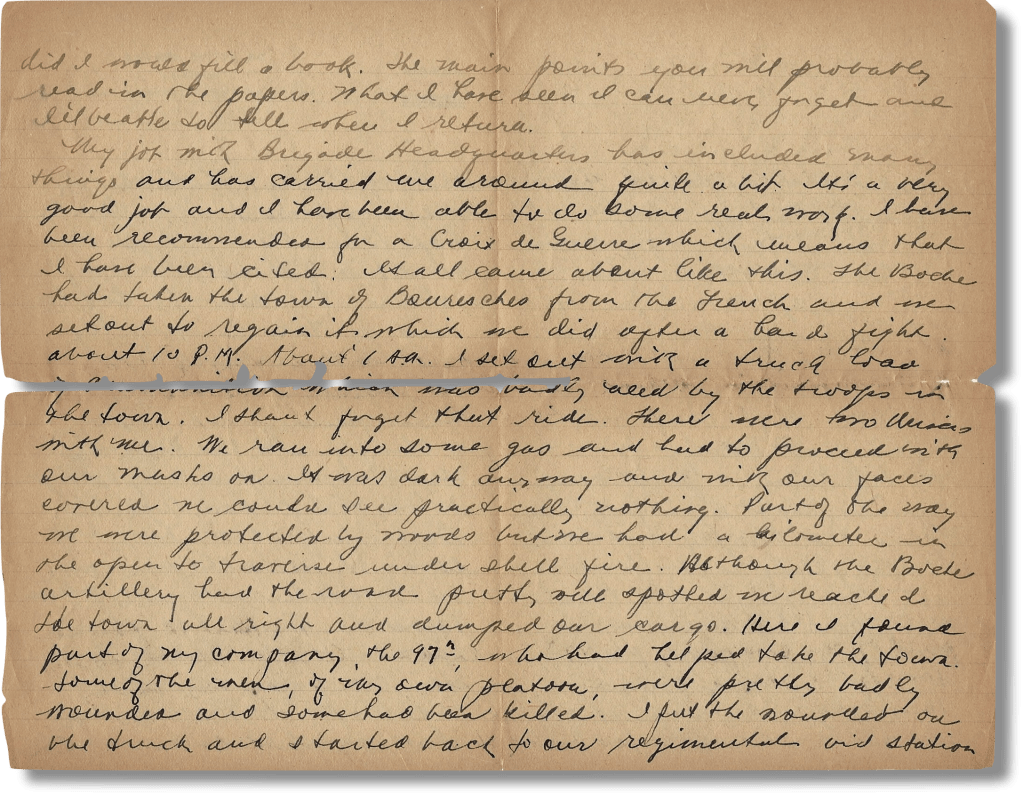

We have taken a good many prisoners—300 today, in fact. Most of them are hungry and some were as young as 18. Some said their officers told them there were no Americans in France and at first they thought we were British. I can’t go into details of the past few days for if I did, I would fill a book. The main points you will probably read in the papers. What I have seen I can never forget and I’ll be able to tell when I return.

My job with Brigade Headquarters has included many things and has carried me around quite a bit. It’s a very good job and I have been able to do some real work. I have been recommended for a Croix de Guerre which means that I have been cited, It all came about like this. The Boche had taken the town of Bouresches from the French and we set out to regain it which we did after a hard fight about 10 p.m. About 1 a.m. I set out with a truck load of ammunition which was badly needed by the troops in the town. I shant forget that ride. There were two drivers with me. We ran into some gas and had to proceed with our masks on. It was dark anyway and with our faces covered we could see practically nothing. Part of the way we were protected by woods but we had a kilometer in the open to traverse under shell fire. Although the Boche artillery had the road pretty well spotted, we reached the town all right and dumped our cargo. Here I found part of my company, the 97th, who had helped take the town. Some of the men of my own platoon were pretty badly wounded and some had been killed. I put the wounded on the truck and started back to our regimental aid station. At one point in the road we hit a shell hole and almost turned turtle but luck was with us and we reached the aid station without mishap. One young chap who had ben my orderly when I was with the company had died on the way in. The others for the most part were in pretty bad shape but their chances of recovery are good. I have the satisfaction of knowing that if it hadn’t been for that truck ride, they might never have received the medical attention which probably saved their lives.

I don’t know who it was that recommended me but I think it was our Brigadier General. I didn’t think so much of the ride at the time and had almost forgotten it when I saw an account of it in the Paris edition of the New York Herald. I don’t yet know how they got hold of it. They gave my name as Donald. [ ] Donald was a noted Princeton athlete, well-known throughout America, but evidently not well known to the writer.

General Pershing has visited Brigade Headquarters on a few occasions and expressed himself as proud of the Marines and he has right to be. Perhaps we will be relieved soon and given a rest and perhaps our long overdue furloughs. I will admit that I need a bath badly for I haven’t changed anything on my body in four weeks, nor have I had my clothes off in that time. I don’t seem to have any cooties though…

I am still healthy and happy and more than ever eager to kick the Boche. The silver lining to the present dark cloud is that the Americans are here and the more there are, the sooner the war will end. The Germans can’t get to Paris and in time we’ll start pushing them back from whence they came. I’ll be able to do better in my writing from now on, I think, as things have quieted down a bit. I know the times are fraught with anxiety for you but things will take their course and we must hope and pray for the best. Love to all the family and my best to you. Yours devoted son, — Billy