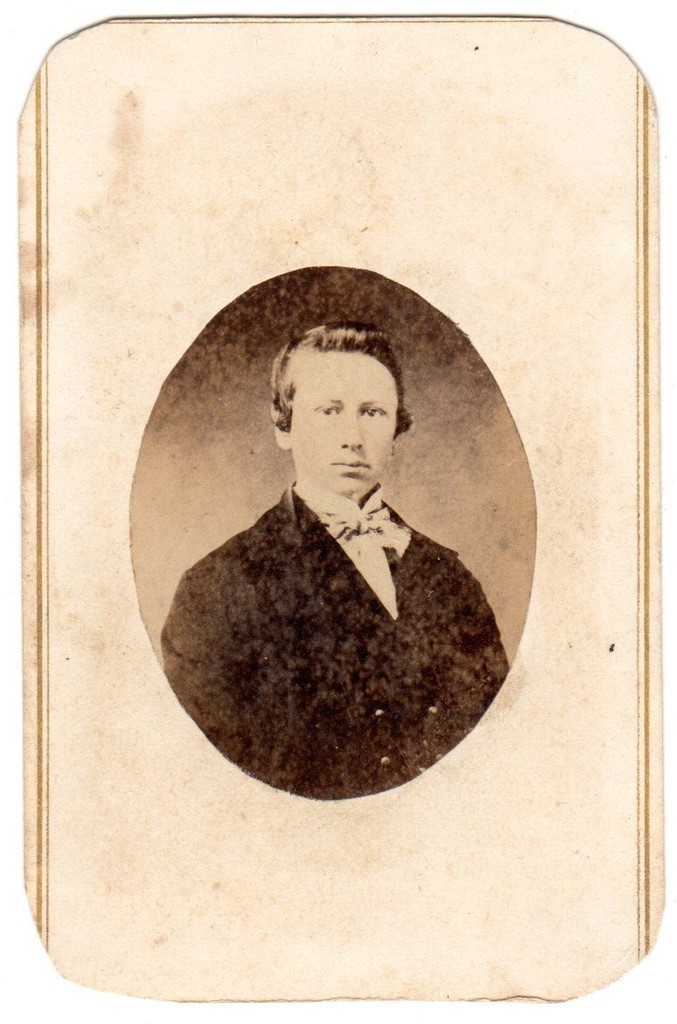

These letters were written by Emmett H. Waller (1843-Aft1890) who enlisted in late December 1863 at Burke, New York, to serve three years in Co. I, 14th New York Heavy Artillery. He was mustered into the company officially on 4 January 1864. At the time of his enlistment, he gave his birthplace as Pierrepont, St. Lawrence county, New York, his occupation as “mechanic,” and he was described as standing 5 feet 7 inches tall, with blue eyes and dark hair. A note in the muster roll abstracts claims that he was on detached duty from the regiment, serving as a clerk in the headquarters of the 1st Division, 9th Army Corps.

Emmett was the son of Asabel Waller (1799-1876) and Jerusha Dorothy (1804-1881) of St. Lawrence county, New York. Emmett’s father earned his living as a joiner and also served as the postmaster in East Pierrpont.

After he was discharged from the service in 1865, Emmett moved to Muskegon, Michigan, where he worked he opened a business under the name “Waller & Beerman” selling pianos, organs, and sewing machines. Emmett did not marry Lucy to whom he sent “a hundred kisses” to close the following letter. He did not marry until 1881 when he took Elizabeth (“Betsy”) Houghton as his wife.

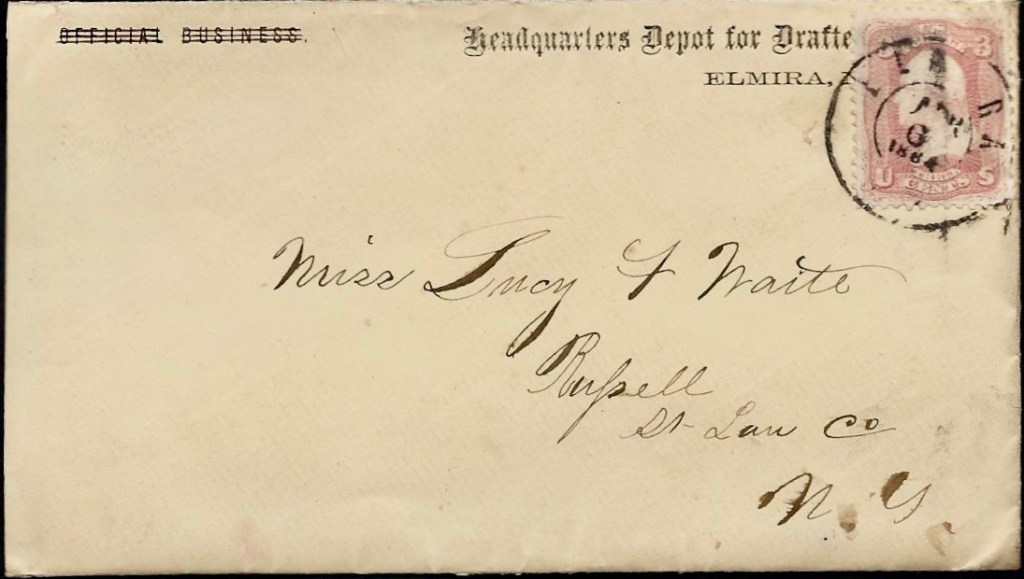

Letter 1

Emmett wrote this letter from Elmira, New York. It was sent on official stationery of the “Headquarters Depot for Drafted Men” which was operated almost as rigidly as the prison sited there for Confederate soldiers. By this late date in the war, drafted men had to be watched closely to make certain they did not desert as many of them were there involuntarily. Rigid rules were laid down to keep draftees in camp while they were being organized and drilled for assignment to Union regiments.

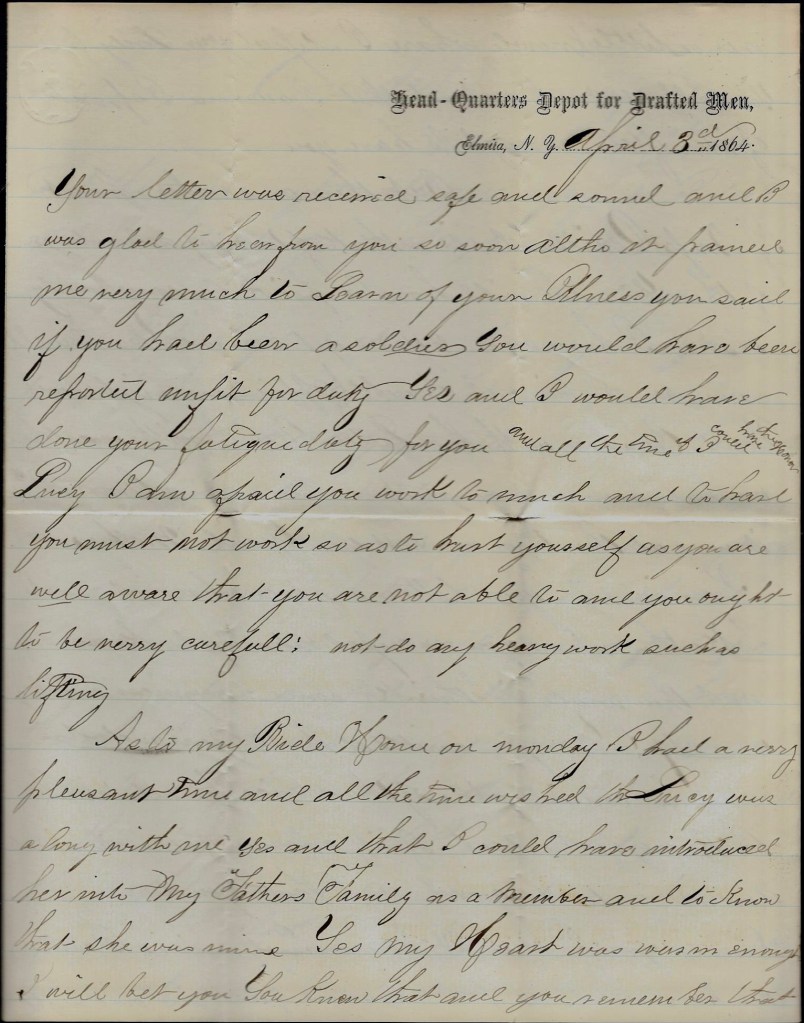

Headquarters Depot for Drafted Men

Elmira, New York

April 3rd 1864

Your letter was received safe and sound and I was glad to hear from you so soon although it pained me very much to learn of your illness. You said if you had been a soldier you would have been reported unfit for duty. Yes, and I would have done your fatigue duty for you and all the time if I could have the honor.

Livey, I am afraid you work too much and too hard. You must not work so as to hurt yourself as you are well aware that you are not able to and you ought to be very careful—not do any heavy work such as lifting.

As to my ride home on Monday, I had a very pleasant time and all the time wished that Lucy was along with me. Yes, and that I could have introduced her into my father’s family as a member and to know that she was mine. Yes, my heart was in enough [word missing], I will bet you. You know that and you remember that tree or little knoll where I kissed your lovely face. You will remember about that, I presume. I speak of it often enough to have you…

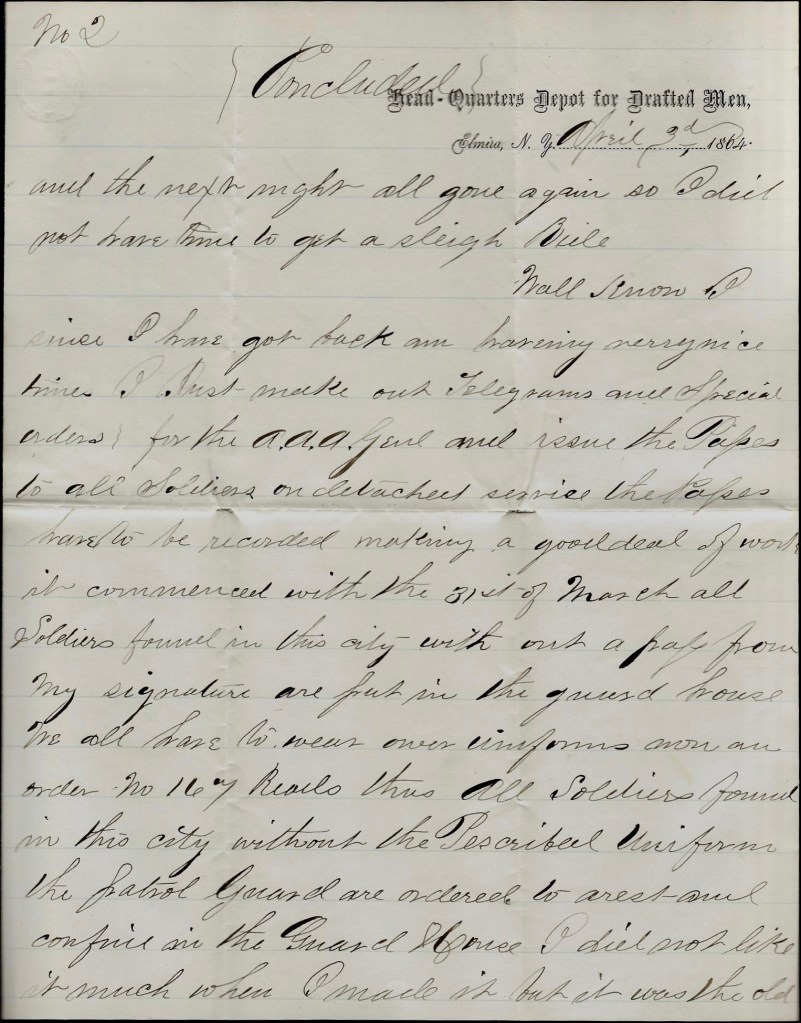

Since I was at home or since I came [here], we have had a foot of snow fall in one night and the next night all gone again so I did not have time to get a sleigh ride.

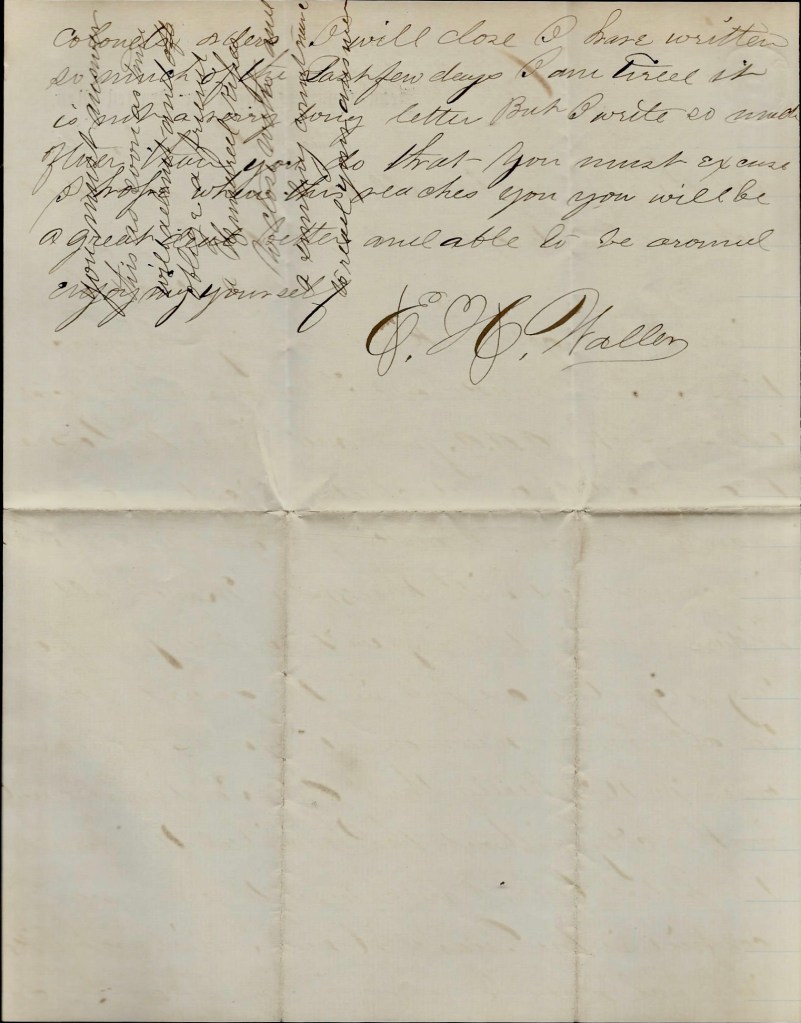

Since I have got back, am having very nice times. I just made out Telegrams and Special Orders for the A.A.A. General and issue the passes to all soldiers on detached service. The passes have to be recorded making a good deal of work. It commenced with the 31st of March, all soldiers found in this city without a pass from my signature are put in the guard house. We all have to wear our uniforms now. An order—No. 16—reads thus: “All soldiers found in the city without the prescribed uniform, the patrol guard are ordered to arrest and confine in the guard house.” I did not like it much when I made it but it was the old Colonel’s orders. I will close. I have written so much of the last few days, I am tired. It is not a very long letter but I write so much oftener than you do, that you must excuse. I hope when this reaches you, you will be a great deal better and able to be around enjoying yourself.

— E. H. Waller

You must answer this as soon as time will admit and oft oblige a friend. Hundred kisses to close with and a smiling countenance is read your answer.

Letter 2

In Camp Fort Haskell

January 28, 1865

Lucy,

I have written you so often of late and have received no answer. I well know the reason—or at least think this it, that you were offended at the photograph I sent you entitled “excuse my back, sir.” The reason I sent it was this. It was given me and I thought it a very comical picture and still not bawdy. I sent it with the idea that you would laugh at the novelty and think, yes, and know, that I meant no evil intent. You have often told me that I was gentlemanly in conversation, never used vulgar language, and God knows I never thought of wrong in your presence, nor any other, but that of true devotion. I have often thought, yes, and hourly, that had I not sent it, I would give hundreds of dollars and then the thought has entreat my mind can it be that she has only been waiting for me to do something for you to say farewell.

Oh! I fear for myself what my end will be here. I am in the land where the enemy’s missiles fly thick and fast, and since I came, I have not felt the least fear of. I do not care it seems whether I lay my bones here or not. Were I dead, my mind would be at rest and you would not be troubled with my declarations of love. You would feel at rest that you were freed from a troublesome trouble.

I have been on picket 24 hours and on fort guard 4 hours only since I joined this Regiment, but visit the picket line every night to trade with the Johnnies and visit. The Johnnies meet us half way and often come into our lines—called picket pits, we promising them that they may go back and we let them too. [But] sometimes our officers finding them in our pits, keep them. This is wrong when they had the promise to go back. There was a Lieutenant of theirs come over last night and stayed by his own request. They are deserting very fast. They reported last night that Charlestown was taken by our folks; also that we took Gen. Joe Johnston. I have not invested much stock in this yet; perhaps it is true. I will close now and go down and see the Johnnies and have a chat. Then on the morrow if nothing happens, I will finish this. It is now 10 o’clock eve. Goodbye.

Good morning, Lucy. I left you last eve to go down and see the Johnnie Rebs and met four of them at our picket pits. They had cartloads of tobacco and wanted hard tack bread meat coffee knives and almost everything but tobacco. They say they will starve in a short time. Their only hope now is that they be a settlement and cessation of hostilities. They have the story now that there is an armistice of 80 days. The most of them say they are only waiting for their pay which they expect to get on or before the 15th day of March. Then they can buy things with their money and desert to our lines. We have various rumors—first, that we are to be relieved and move to the left; others that we are going to New York; and others that we are to go to Baltimore. I think we shall stay here and fight just when there is any fighting to do.

I was over to see Alvah Beach’s grave the other day. It is only a few rods from here. Many of the 14th boys are buried around these works. It is but a few rods from here where our regiment made the charge on the 30th of July at the great explosion [see Battle of the Crater] and this very ground was fought over. There are dead you can see their bones laying between the picket posts on top of their knapsacks just as they fell. It is horrible—horrible! The boys tell me that there was some of them lay there for 3 and 4 days wounded and unable to walk or crawl that had to lay there and starve to death, they hearing them groan all the time, but darst not go after them. One boy had a brother in this place. He heard his groans for 3½ days [and] finally could not endure it longer. He got a long rope and threw it to him in the night and succeeded in getting him and saving his life. He had his thigh broken.

I am not well now. Yesterday I went to the doctor for medicine. I cannot speak a loud word on account of a severe cold on my lungs. The doctor excused me yesterday from all duty. Gave me 4 quinine powders to take one every three hours. I did take one every three hours and threw them in the fire today, I did not go near him and tomorrow he goes home on a furlough. Just as well. Doctors in the army are a nuisance.

I received a letter from home this week saying my Mother had gone to Ogdensburgh on a visit. My brother’s wife who lives there is very sick. Her old complaint consumption. I fear she will go this time to her long home. I will close for this time and wait an answer. — Emmett

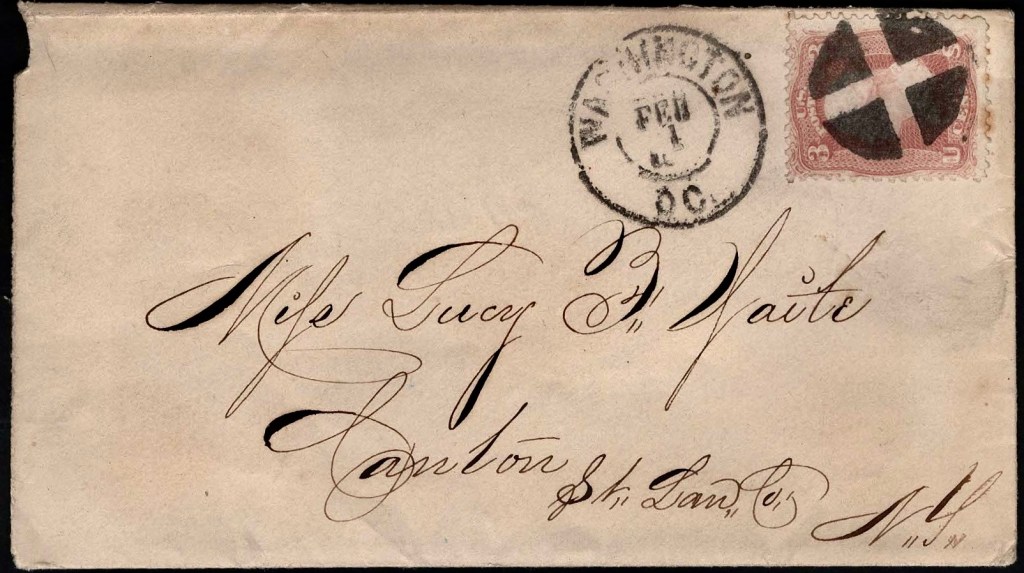

Co. I. 14th New York Heavy Artillery, Washington, D. C.