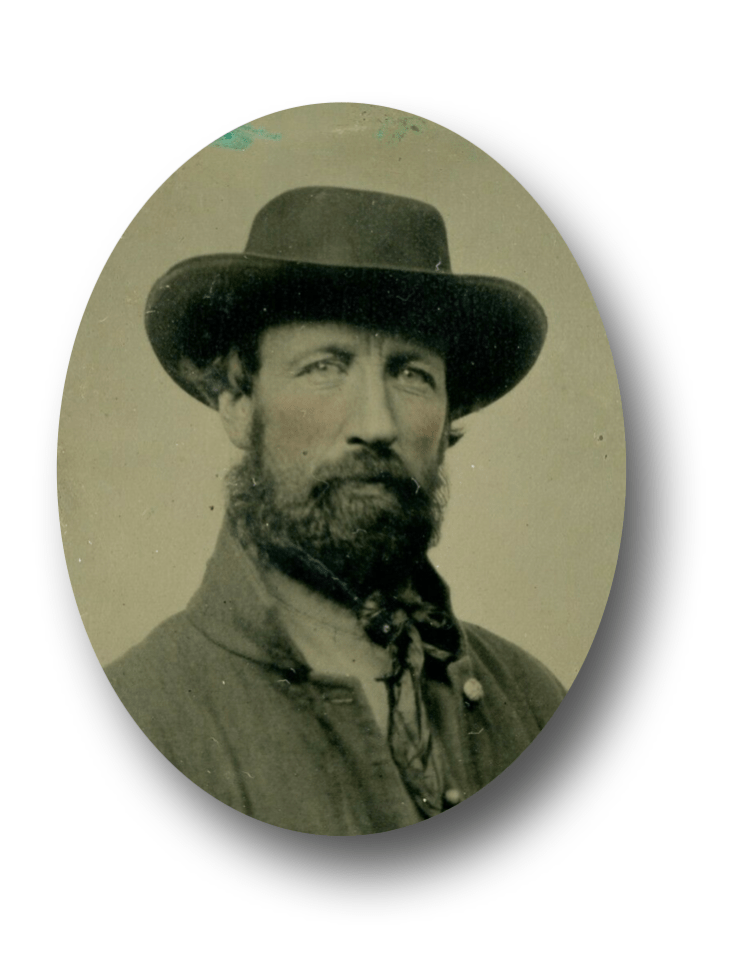

The following letter was written by Henry Hirst Bentley (1832-1895), the son of Hiram Bentley (1802-1896) and Hannah Swartwout (1803-1863) of Pine Plains, Dutchess couty, New York. Without any money, Henry left his parents home and went to New York City in 1852 when he was twenty years old, landing a job as a reporter for the New York Tribune. He subsequently helped to organize a company to promote the use of printing telegraph machines known as the New York City and Suburban Printing Telegraph Company. When that undertaking failed, he organized a system of depositories for telegraph messages and then established the Madison Square office known as Bentley’s Dispatch.

When his health failed, he took some time off to regain it and then settled in Philadelphia where he joined the staff of the Philadelphia Inquirer and was assigned duty as a war correspondent in 1861—a paper that would earn a well-deserved reputation for reporting military action in an objective manner (unlike other papers). Bentley joined a stable of correspondents that were seasoned and knowledgeable. A good team—so good that a correspondent from a rival newspaper complained to his boss that the “the Inquirer people knew more about the war than did most of the generals.” Henry may have been a bit more haughty than his colleagues, however, as they sometimes referred to him as “The Water Spout Man”—always bragging and babbling.

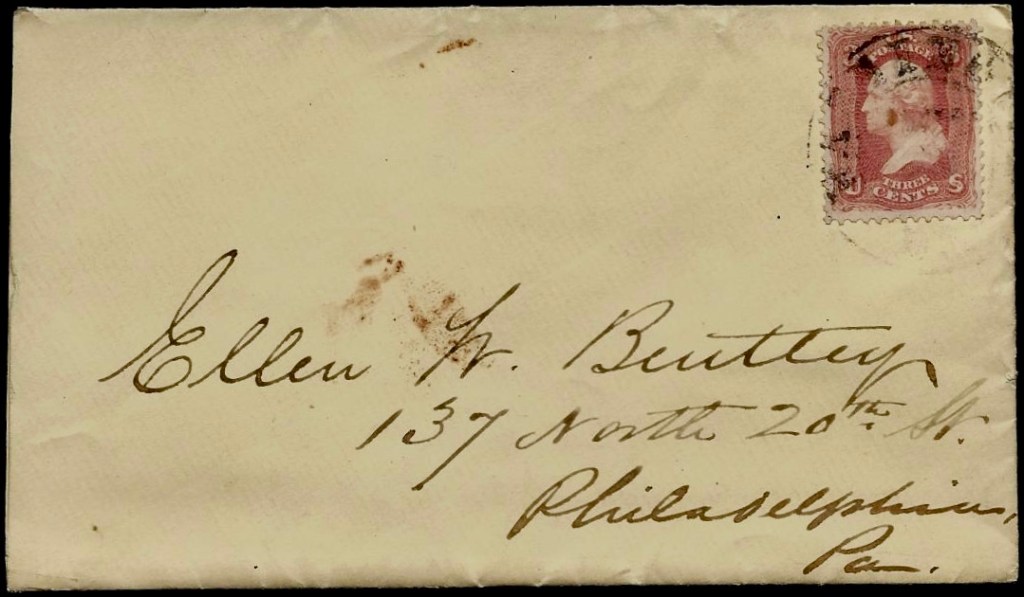

It was while working as a war correspondent that Henry wrote this letter to his wife, Ellen Widdifield (Penrose) Bentley (1833-1915)—the daughter of a Quaker family—with whom he married in 1860. The date of the letter is unknown. I have suggested 1861 while Henry was much of the time in Washington D. C. though he mentions something about the “Court Journal” which might suggest a later date. I found a reference to the Washington Star being considered Mr. Lincoln’s “court journal” but I don’t know if Henry changed to that newspaper during the war.

Henry’s name appears in the papers throughout the war. In the 19 February 1862 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer, it was alleged that he and Mr. Schell of Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, “entered Fort Huger [on Roanoke Island], after its abandonment by the Rebels, in advance of the army, and hauled down the Rebel flag.” In another issue of the same paper published on 15 April 1862, he was reported as having been taken prisoner at the Battle of Shiloh but subsequently escaped after having been robbed of everything but his “pantaloons and boots.” Legend has it that Bentley hadn’t really escaped so much as the Confederates let him go because “they had grown weary of listening to him talk.”

After the war, Henry organized the Philadelphia Local Telegraph Company and also became head of the Gold and Stock Reporting Telegraph Company and President of the Bell Telephone Company of Philadelphia. He was a close friend of Thomas A. Edison.

Transcription

Washington [D. C.]

21st, 8 p.m. [1861]

My Dear Baby,

Thy sweet little missive arrived this morning and I read it over several times before I could become satiated in the least degree.

There seems but little that is new and that is more suitable for newspaper reading than for a letter to a wife. I am still enjoying excellent health and spirits considering the clouds of dust that once more assail us. Mud or dust is peculiar to Washington’ there is no medium.

I presume thee saw my dispatch yesterday announcing that Mrs. Lincoln would pass through Philadelphia for the East. That was my first “Court” announcement, in advance. Some of them laugh at the Inquirer having suddenly become Court Journal. Well, it merely happened so, she having told me that she intended going to Cambridge 1 in a few days. I asked her to please let me know when she was going as it would be a favor. So the evening before she started, she sent word down to me with her compliments, stating that she would probably be gone 2 or 3 weeks, and that when she returned, they would be pleased to see me at the White House, whenever I chose to call. She told Friend Newton that there was “some difference between the Chevalier Wikoff 2 and Mr. Bentley,” and, that she was “very much pleased wiith Mr. Bentley’s manner.”

As to the depreciation of paper money, of course all bank notes are depreciated the same as Treasury Notes. Gold is the stand point, so for instance, gold is worth today about 130 cents on a dollar—that is, a gold dollar is worth 30 cents more than a one dollar paper note of the best kind. My sweet wife thinks she can see the way clear, therefore I am perfectly willing she shall do just what she proposed about the cloak and dress. I thought it best to call her attention to the matters that appeared before me at that time and now I leave it to you own good judgment.

Should I not come up 7th Day, I will send thee some more funds. My coming, baby knows, depends upon what word I get from her, as however much I might desire to see my sweet child, and hold communion with her in every ordinary social way, she knows her husband’s little failings and he could never bear the comments which his baby might be obliged to impose upon him. Dear me! When shall I have my little wife to fondle on and caress again? Hasten the day—or night.

It affords me some poor consolation that my darling baby dreams of me if she is not permitted to go beyond that. My sleep is sweet and I sink into it with sweet thoughts of my own dear one far away in her couch, snugly stowed away.

By the way, in the course of conversation the other day, Mrs. Lincoln in talking about various people with whom she was perpetually bothered, mentioned one Sweeney of Philadelphia—rather a beau looking gent. I didn’t enter into any particulars but it appears among many others who have axes to grind and wants to get on intimate terms must be the gent I have heard them mention as Beau Sweeney. I was asked if I knew him but I said I had heard of such a person but did not know him. He pesters the life out of them and she says she cannot give audience to everybody, however much she desires to please their constituents.

I am glad Willie gets along well with his recruiting. Give my love to all the family and tell them I am extremely well. I forgot to say before that the Dr. had a slight hemorrhage of the lung last night. He looks very bad. Rachel is quite smart. And now I will close by sending my wife’s untold love and hope I shall hear from her soon and satisfactorily. Thy husband, — Henry

1 Mrs. Mary Lincoln would have wanted to visit Cambridge because her son Robert was attending school there. Robert left for college in 1860, but during the next four-and-a-half years, he became his mother’s traveling companion. Mother and son both loved traveling, and whenever Robert had a break from college (at Harvard) he and Mary were usually on the road somewhere together. Robert met his mother during many of her trips to New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, where the two would not only spend hours together shopping in the most fashionable stores, but also entertaining with social, political, and military leaders. Mary also visited Robert at Cambridge when she could, at least once a year. Every summer mother and son spent one to two weeks traveling around New England on vacation: in August 1861 to Long Branch, N.J. for two weeks; in 1862 to New York City for one week; in 1863 to the White Mountains of New Hampshire for one week; and in 1864 from Boston to New York City to Manchester, Vermont for a total trip of about ten days. [See Lincoln Lore]

2 Chevalier Henry Wikoff (1813-1884) was a charlatan who managed who managed to flatter his way into Mrs. Lincoln’s inner circle. “In almost all things, he was disreputable if frequently charming,” He used his access to the White House to leak information anonymously to a New York newspaper. [See Mr. Lincoln’s White House]