The following letter was written by Benjamin Willson Briggs (1842-aft1920) to his older sister Rhoda Sophia Briggs (1840-1921). They were the only children of Asa Barnard Briggs (1785-1863) and Jane Winslow (1788-1870) of Pierrepont, St. Lawrence county, New York. Rhoda was yet unmarried in 1865 when this letter was written but married Howard William Burt in 1875. Benjamin married in 1867 to Jane S. Striver (1843-1919) in Springfield, Illinois.

From the content of the letter and from the envelope it appears that in 1865, Benjamin was working for the Assessors’s Office of the US Internal Revenue Service, 8th Illinois District. We know that he married Jane in Springfield in 1867 which leads us to conjecture that he may be the same “Benjamin W. Briggs” of Pekin indicted in 1876 on petty charges of conspiring to defraud the United States in matters related to tax collecting. Later in life he appears to have taken his family to Omaha, Nebraska, where he worked as a baggage agent.

In this letter, Benjamin describes the emotional impact on himself and the community of Bloomington, Illinois, upon receiving news of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. He also shares a remembrance of having been at a Ford’s Theatre performance the previous September when the news of the fall of Atlanta was announced, in stark contrast to the news of the assassination. He also, surprisingly, shares his wonderment that an assassination attempt had not been made previously during Lincoln’s daily sojourn to the cottage he kept at the Soldier’s Home. Finally he mentions briefly the arrest and near hanging of a resident in Bloomington who celebrated Lincoln’s death.

[Note: This previously unpublished letter was graciously made available for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared expressly by the Sic Parvis Magna, Gratias Lesu Collection.]

Transcription

Bloomington, [Illinois]

April 16, 1865

Dear Sister,

I have received two letters from you since I have written to you. I will now endeavor to answer them both at once but I am afraid that it will be but a poor attempt for I do not feel much like writing letters today. The excitement occasioned by the terrible news of yesterday has not yet entirely subsided and therefore it is difficult for me to keep my thoughts together long enough to get them upon paper. Abraham Lincoln is no more!

No longer ago than day before yesterday the people here were all elated at the glorious prospects before them. Recruiting to be stopped and the expenses reduced. Surely the end was drawing nigh. All were gay and joy gleamed from every countenance. All were congratulating each other that this cruel war was over. What a contrast was yesterday—a fearful gloom overshadowing every countenance while the doleful gun, the tolling bell, and the city draped in mourning told of the terrible bereavement which the Nation had been doomed to suffer. The greatest and noblest of men, the national Chief Magistrate, had been stretched upon a bloody bier by the hand of a skulking assassin. Citizens looked each other in the face in blank astonishment while deep in their eyes was a troubled look that bespoke of sorrow mingled with terrible vengeance.

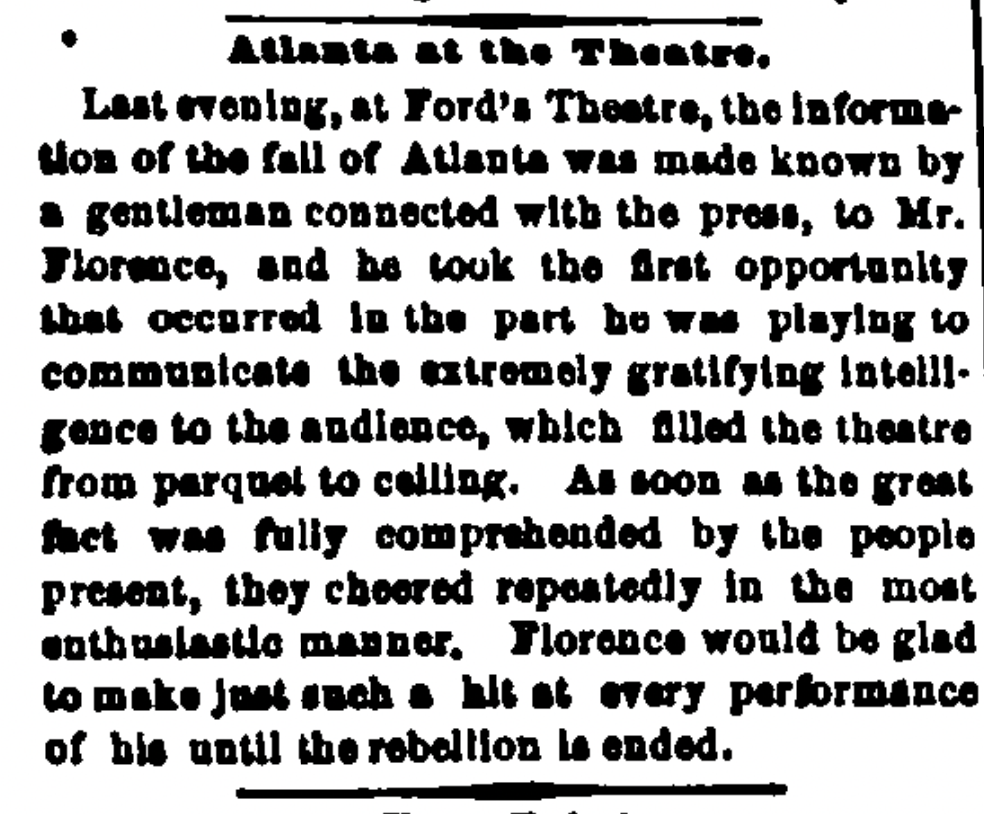

Last summer while I was at Washington I twice visited Ford Theatre. Once, while there, in the very midst of a play, the stage manager came forward and said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, official intelligence has just been received that Atlanta is ours. Gen. Sherman’s forces entered it at three o’clock this morning,” and he added with a triumphant air, “you can see what a man can do that gets up in the morning.” The applause was loud and long. Every loyal heart was full and every loyal mouth was open. The audience nearly all arose to their feet, hats and handkerchiefs were waved, and cheer after cheer was lustily given. The old theatre resounded with the welcome of good news. The tumult would subside at times at times seemingly to be renewed again with greater vigor. When the joy had spent itself, silence again resumed its sway and the play proceeded.

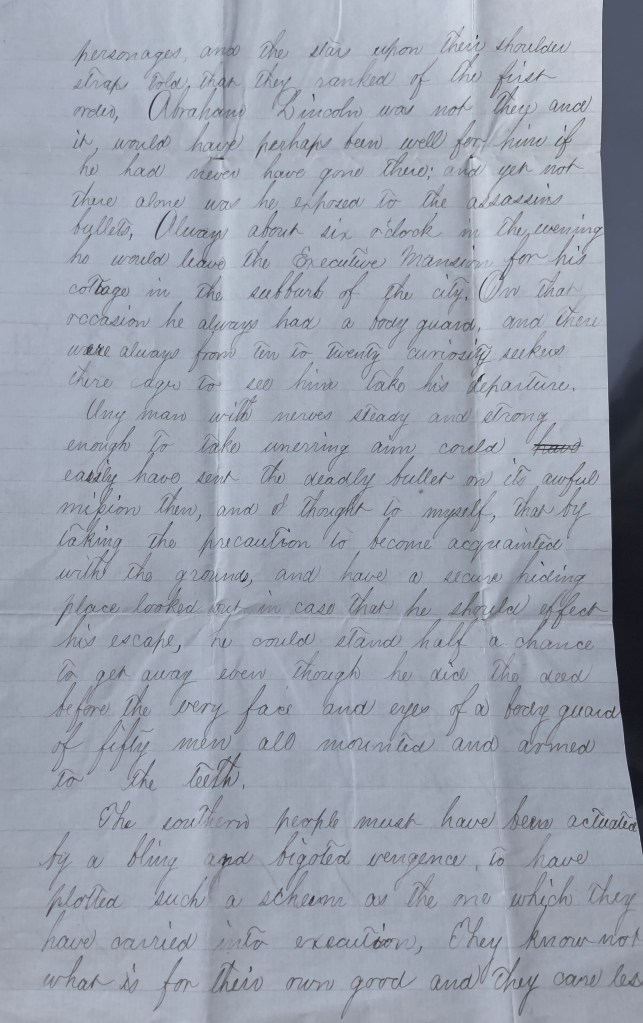

While sitting there that night enjoying the good news and the theatre, how little did I think of the awful, great, real tragedy so soon to be enacted there. I looked at the private boxes well. I remember they were filled with military personages, and the stars upon their shoulder straps told that they ranked of the first order. Abraham Lincoln was not there and it would have perhaps been well for him if he had never have gone there; and yet not there alone was he exposed to the assassin’s bullets. Always about six o’clock in the evening he would leave the Executive Mansion for his cottage in the suburb of the city. On that occasion he always had a body guard and there were always from ten to twenty curiosity seekers there eager to see him take his departure. Any man with nerves steady and strong enough to take unerring aim could easily have sent the deadly bullet on its awful mission then, and I thought to myself that by taking the precaution to become acquainted with the grounds, and have a secure hiding place looked out in case that he should effect his escape, he could stand half a chance to get away even though he did the deed before the very face and eyes of a body guard of fifty men all mounted and armed to the teeth.

The southern people must have ben actuated by a blind and bigoted vengeance to have plotted such a scheme as the one which they have carried into execution. They know not what is for their own good and they care less. They have killed a great and noble man—one whose bosom was incapable of harboring a single revengeful feeling—one who though he has been stern and unceasing in his endeavors to crush the rebels, has always held the olive branch to their view and who has declared to them that if they would lay down their arms, he would exercise “justice tempered with mercy.” Who will pardon Jeff Davis now? Aye, the bullet that laid Abraham Lincoln low killed the southerners best friend and roused a longing for revenge in northern men that one generation cannot clear away.

I cannot stop to tell you of what was done here today. How a man said if he thought the news was true, he would swing his hat high—how the mob got after the wrong man—how they finally got the right man—and how, but for the vigilent energies of the police, they would have swung him higher than he could have swung his hat. 1

It is getting dark and I must close. I have written much longer than I thought I possibly could when I sat down. My love to all with a big slice for yourself.

Your affectionate brother, — B. W. Briggs

1 I could not find and newspaper account of this incident in Bloomington, Illinois, but I don’t doubt it. There were numerous incidents of Union soldiers being arrested for saying similar things upon hearing of the assassination of the President.