The following letter was written by a young man named L. Russell to his friend, Daniel H. Whitney (1820-1904) of Seneca Castle, Ontario, New York. Daniel was the son of William E. Whitney (1770-1872) of Maine and Elizabeth Howard (1799-1900) of Geneseo, Livingston county, New York.

Transcription

Geneseo

Saturday, December 20th 1841

Friend,

According to promise and the weather being stormy, I have nothing to do and can as well as not, spend my idle hours in writing to you. Lord whistles the wind around the old mansion. The snow is cutting all the fantastics that imagination can picture. A dense cloud obscures the heavens from which the snow is incessantly falling which, however, finds no rest on the earth for Boreas pipes loud and long and appear to be moving the snow about from place to place by the job. And to speak the truth, he is doing wonders around your father’s house and out buildings. In one place the snow is piled up not unlike a sugar loaf. In another may be seen the hull of a ship turned bottom side up with the figurehead Garha and moulded in the finest possible manner. But I am notable to give a full account of the tenth part of the wonderful, twisting and windings of this boisterous old Boreas for when he has nearly finished a piece of work, he destroys to build another.

I feel uncommon dull today although I am sitting by a fine blazing fire in the east chamber. But I suppose it is owing to the dreariness of the weather or to love—maybe both; but I need not be dull if the sighings of the wind has anything enlivening in its tuneful notes.

But to my promise—my journey. You know that I left your father’s for Pennsylvania on the 18th of October. But I shall say nothing of the five first days save that they were anything but agreeable and shall commence with the sixth, Saturday, October 23rd. I left the village of Bolivar at six in the morning in a snowstorm and walked to Smith Settlement over the gloomy hemlock hills to the village of Millgrove where I came to the Allegheny River, which is about eighty yards wide at this place and not motion enough in the water for me to perceive it running. Here I took dinner and concluded to stay until the snowstorm was over. I had no sooner finished my meal than looking out I found the storm had in measure abated. At the west, the clear blue was visible. I directly started on my journey for the village of Smethport, the distance being twenty miles and not a public house on the whole route.

Millgrove is in the extreme bend of the river and on the line between the state line of New York and Pennsylvania. My route lay up the stream which was an outcast by south course and the soil of a sandy loam for a mile or two. Corn grows well on this soil by what little I see though there but little attention paid to cultivating the lands in this section of country. Lumber is the all absorbing business of this part of the world save now and then hunting, drinking, and lawing. After leaving Millgrove I found a tolerable good road for a mile or two. the clouds having just passed over the sun shone out bright and clear. The snow on the mountains mixed with the evergreen pines and hemlock gave the scene a half melancholy, half cheerful appearance, whilst the reflections of the sun on the surface of the Allegheny [river] made its crystal waters as they meander through the valley cast many a pleasing reflection on the sides of the mountains.

But these few sunshiny minutes were of but short duration. I had not walked over three or four miles before I perceived at my right hand a dense black cloud arise above the western mountains which soon obscured the sky and blasted all my hopes of having better weather or roads the remaining part of my journey. The vivid flashes of lightning that darted through the clouds whilst the tremendous thunder that rolled along the valley of the Allegheny and its tributaries doubly echoing amongst the cliffs of the mountains. These with a heavy shower of rain incessantly falling added to the badness of the road which after leaving Millgrove a few miles are of about red clay and the mud was about half boot deep, put me out of all patience and I damned the road and cursed my own folly. Ten miles above Millgrove I crossed the river and had to walk a mile on, up and down hill in the same clay soil. These short hills are made by small brooks and rivulets putting into the river. There is a junction of the river a mile above where I crossed it and I followed up the west branch which is called Potato Creek. The turnpike here runs nearly on a south course. I was sometimes in sight of the stream over the points of high lands where the road was barely wide enough for two wagons to pass with a majestic mountain on one side and deep precipice on the other and sometimes three or four miles between houses.

The road over these hills was much better to walk upon than the road on the level valley. I tried my speed this afternoon and endeavored to reach the village of Smethport but fell short five miles when night overtook me. I stopped at the house of an old farmer by the name of Sartwelland put up for the night, tired and weary and angry with myself for having attempted a journey over this mountainous [terrain] at this advanced and inclement season of the year. The rain having poured down incessantly the whole afternoon, I was drenched to the skin with my feet wet and sore, having walked thirty-five miles. I dried my clothes and went to bed at an early hour when sleep soon overtook me. But it was neither sound nor undisturbed for I went through all the toils of the past day and was sunk in the mud to the depth of forty feet where I remain until I awoke the next morning.

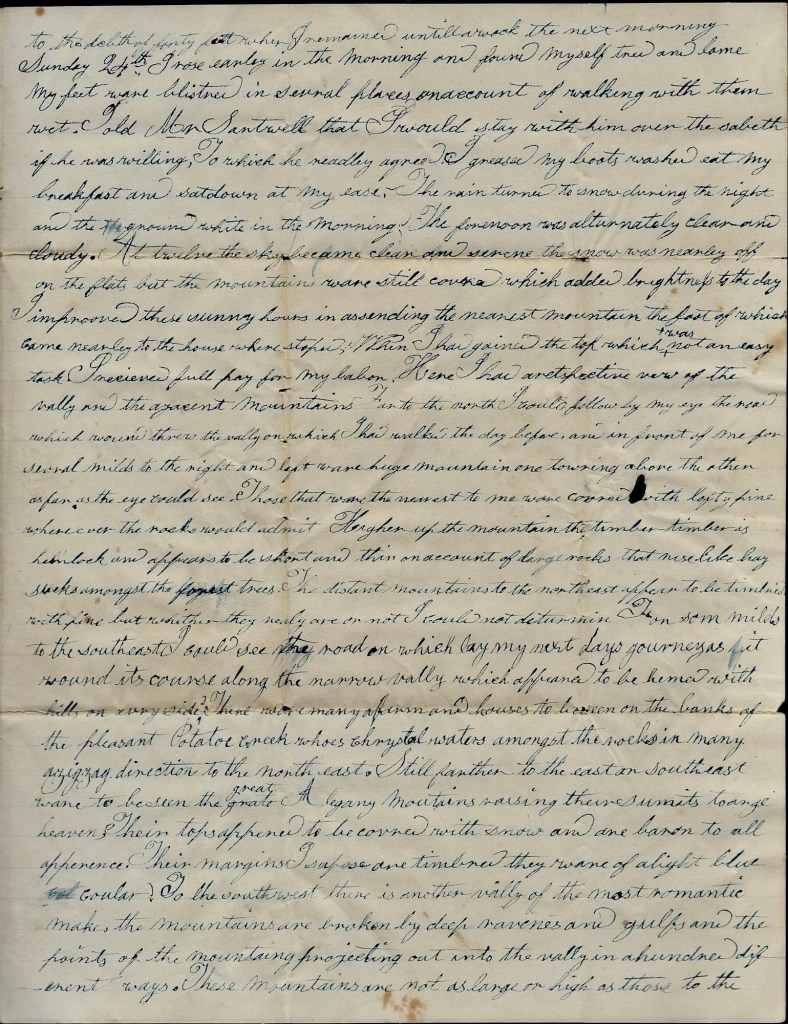

Sunday, 24th. I arose early in the morning and found myself tired and lame. My feet were blistered in several places on account of walking with them wet. Told Mr. Sartwell that I would stay with him over the Sabbath if he was willing to which he readily agreed. I greased my boots, washed, eat my breakfast, and sat down at my ease. The rain turned to snow during the night and the ground white in the morning. The forenoon was alternately clear and cloudy. At twelve the sky became clear and serene. The snow was nearly off on the flats but the mountain was still covered which added brightness to the day.

I improved these sunny hours in ascending the nearest mountain by foot of which came nearly to the house where it stopped. When I had gained the top which was not an easy task, I received full pay for my labor. Here I had a retrospective view of the valley and the adjacent mountains. Far to the north, I could follow by my eyes the road which wound through the valley on which I had walked the day before, and in front of me for several miles to the right and left were huge mountains, one towering above the other as far as the eye could see. Those that were the nearest to me were covered with lofty pines wherever the rocks would admit. Higher up the mountain the timber is hemlock and appears to be short and thin on account of large rocks that were like hay stacks amongst the forest trees. The distant mountains to the northeast appear to be timbered with pine but whether they nearly are or not, I could not determine. For some miles to the southeast I could see the road on which lay my next days journey as it wound its course along the narrow valley which appeared to be hemmed with hills on every side. There were many a farm and houses to be seen on the banks of the pleasant Potato Creek whose crystal waters amongst the rocks in many a zigzagging direction to the northeast. Still farther to the east or southeast were to be seen the great Allegheny Mountains raising their summits to angel heavens. Their tops appeared to be covered with snow and are barren to all appearances. Their margins I suppose are timbered. They were of a light blue color. To the southwest there is another valley of the most romantic make. The mountains are broken by deep ravines and gulfs and the pits of the mountains projecting out into the valley in a hundred different ways. These mountains are not as large or high as those to the west or north, which are nothing in comparison to the mountains to the east and southeast. But they are so broken and rocky that they make a more wild and romantic scene.

At two p.m., the weather became cloudy and I descended the mountain in a snowstorm and did not lack for an appetite at supper. More of the mountains in my next. — L. Russell

Your folks are all well and send their love to you. Hickliah, Sidney, Clarissa, and William are at the donation party tonight at the Rev. Mr. Shaw’s. I am tending the Old Mill. There is a plenty of water at present. Mr. Witney, if you have leisure, I would like you to write and inform me what branches you are studying and of your progress or what progress you make. The clock has just struck nine and I must close. Your sincere though illiterate friend.