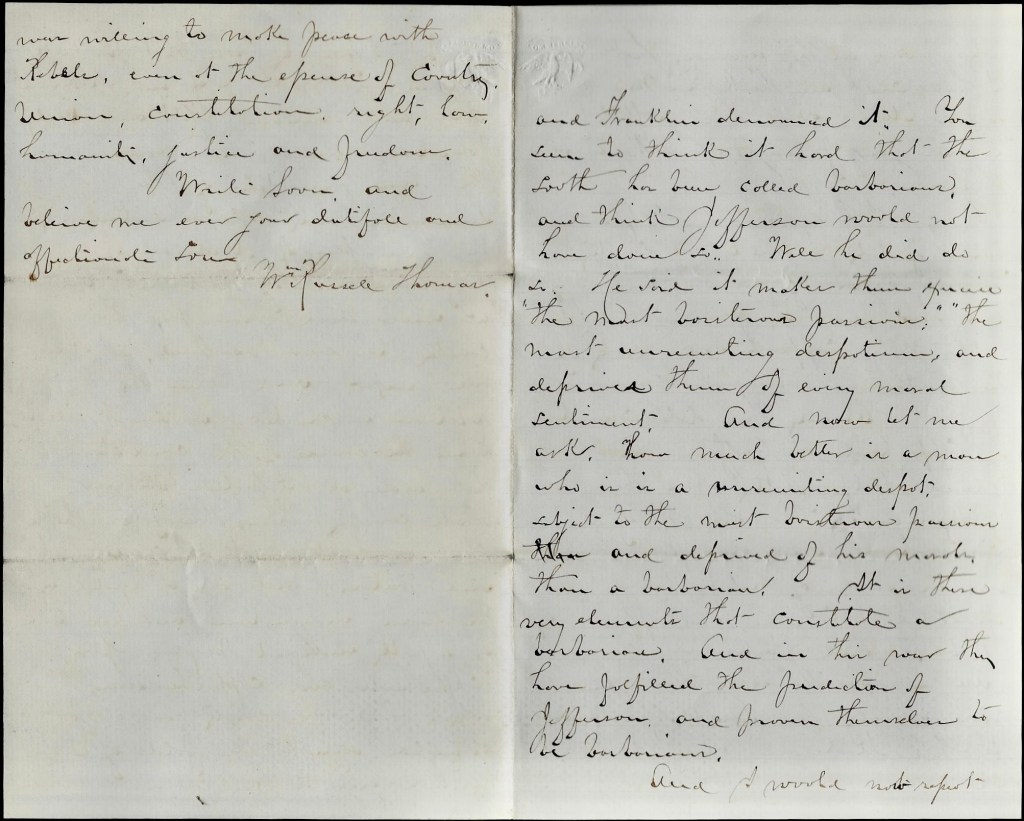

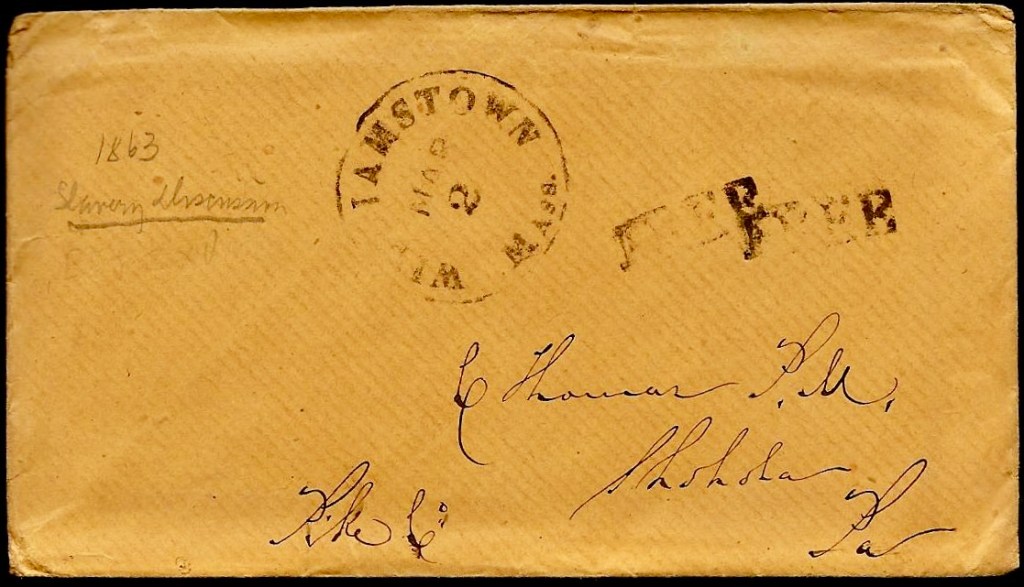

This letter was written by William Russell Thomas (1843-1914) in February 1863 while a student at William College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. William was the eldest son of Chauncey Thomas(1802-1882) and Margaret Bross (1819-1856). His obituary record at Williams College states that “while he was a mere child, his parents moved to Shohola, Pennsylvania, just across the Delaware River from his birthplace [Barryville, New York]. He prepared for college in the academy at Monticello, New York, and graduated from Williams in the class of 1865. During his college course, he took some practical lessons in journalism on the Chicago Tribune, of which his uncle, Lieutenant Governor William Bross, was then chief owner. His first real assignment was the funeral of Abraham Lincoln. Wishing to push on towards the real frontier in the early spring of 1866, he journeyed to Colorado on a stage coach, before the days of western railroads. He spent that summer traveling over the Rockies with Bayard Taylor. In October 1866, he became editor of the Register-Call, a frontier daily paper published in Central City, Colorado. In May, 1867, he went to the Rocky Mountain News as traveling correspondent, in which position he spent several years riding over Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming…He later became the managing editor, which position he held for sixteen years and helped to make it the leading paper of the West.” [Obituary Record of the Alumni of Williams College, Class of 1865]

In this February 1863 letter, William attempts to dissuade his father from embracing the Copperhead movement by illustrating through the words of Jefferson, Washington, and other revolutionary leaders that slavery was a moral wrong and that, if given sufficient time, slavery would have been abolished by a democratic process.

[See also 1863: Willam Russell Thomas to Chauncey Thomas on Spared & Shared 10.]

Transcription

Williams

February 28, 1863

My dear Father,

I have just received your letter and also the box by Express for which I am very much obliged. A token like that from home is always thankfully received for it reminds one that he is not forgotten at home. Aunt E___’s letter I will answer tomorrow, but yours I will answer immediately. I am sorry that you considered the letter to which you refer as a reprimand. I had no such intention and it wsa furthest from my thoughts. I wrote it as a fair and just argument, intended it should be that, and am sorry that it was not taken as such.

As to your remark on Jefferson, I would say I uphold in its fullest extent the right of free speech until it comes to treason which a government has the right to suppress. Admitting this, it leads us to this. A man has a perfect right to denounce slavery, or he has a the same right to praise it. And as long as each party keeps within bounds of the Constitution, each party has the undoubted right to extend their principles.

You try to escape the force of my argument by a quibble—that I cannot show that Jefferson ever belonged to a society to denounce the institutions of one section. Jefferson denounced slavery everywhere—North, South, East and West, as it then was, and when the North, East and West squared themselves upon the principles of Jefferson, did his denounciation of the system not apply just the same, even if it existed in one Section instead of all four? This argument would be sufficient, but to fashion it, I enclose some of his opinions on the point. See extract 1 where he considers it an honor to belong to such a society.

And now, on to [George] Washington. For his views on slavery, I refer you to extract No. 2. A man who would proclaim such sentiments now is called an abolitionist and on such we shall consider George Washington. Whose fault was it that a sectional party was formed! If the North chose to place itself upon the principle of Washington as here expressed, was it not the fault of the section that refused to come up the principles of Washington that the party became sectional! This is the point. The North said with Washington and Jefferson, we believe slavery to be wrong, and called upon the whole country to oppose the sentiments of the founders of our government. The South refused, and the party in the North became sectional by that refusal. Where was the fault? Certainly not of the North. I think the position taken by the sectional party on the mode of stopping the advance of slavery to have been wrong. I believed then—I believe now—that the principle of popular sovereignty was the fairest, most constitutional and most democratic way of stopping that advance. But I believe that every man has the right to denounce the institution of slavery. And if as I have heard you say, slavery is wrong, it is the moral duty of every man to denounce it, just as Jefferson denounced it—just as Washington and Franklin denounced it.

You seem to think it hard that the South have been called barbarians and think Jefferson would not have done so. Well he did do so. He said it makes them exercise “the most boisterous passions”—“the most unremitting despotism and deprives them of every moral sentiment.” And now, let me ask, how much better is a man who is an unremitting despot, subject to the most boisterous passions and deprived of his morals than a barbarian? It is these very elements that constitute a barbarian. And in this war they have fulfilled the prediction of Jefferson and proven themselves to be barbarious.

And I would now repeat what I said in the beginning, that if I have sau anything in my former letter, or in this, which injures your feelings, I ask to be forgiven.

I have written out of a feeling of duty I owe to my country to prevent you, if possible, and everybody else from being numbered with the Copperheaded Party of the North. Already the late convention of Copperheads of Hartford has place itself flatly upon the platform of the Old Hartford Convention, and also upon the very principles of nullification advocated by Calhoun and opposed by Webster and Jackson. Are you willing to go there and place yourself in direct opposition to where Madison and Jackson stood? I cannot believe you will. But I firmly believe that you will stand yet with Dix and Dickerson, Butler and Tremain, Holt and Andy Johnston, under whose guidance the true principles of the Democratic Party will be sustained—the principles of Madison, of Jefferson, and of Jackson. And under these principles the country has ever prospered, so it ever will prosper. And when the rebellion is crushed, as sure it will be, when the powers of the Constitution shall again be respected over our whole country, then the fate which shall be meted out to secessionists and traitors will only be equaled by the scornm indignation, and execution of a justly indignant people upon Copperheads and Copperheadism which, while the country was all but strangled beneath the folds of a wicked, gigantic, and damnable rebellion, was willing to make peace with Rebels, even at the expense of country, Union, Constitution, right, law, humanity, justice, and freedom.

Write soon and believe me ever your dutiful and affectionate son, — Wm. Russell Thomas