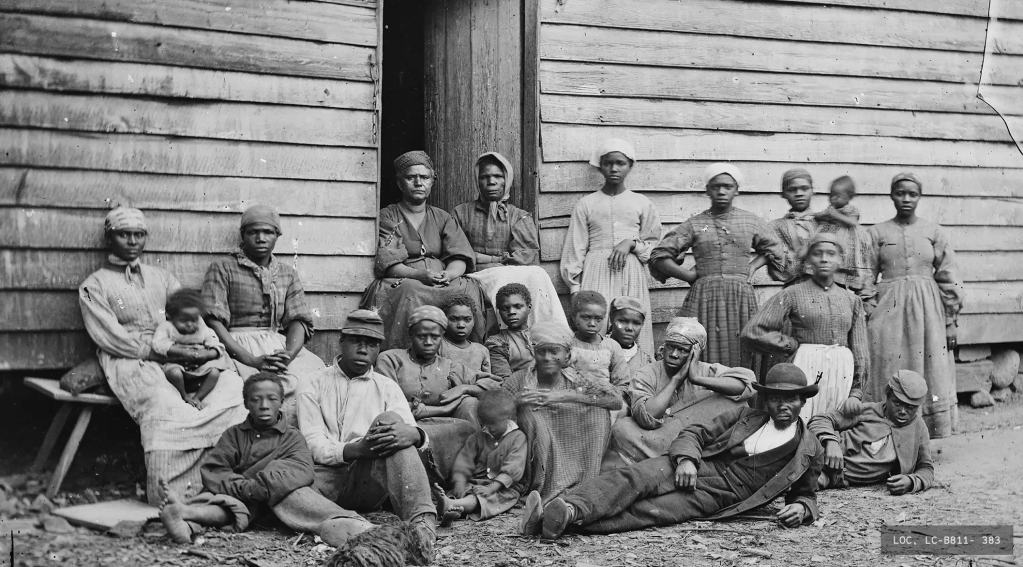

The following 12-page handwritten document contains extracts from letters sent to the Friends’ Association (Quakers) of Philadelphia by agents sent out throughout the South to alleviate the suffering, attend to the needs, and to educate the large numbers of refugee slaves who entered Contraband Camps established by the military in 1863. The misery of the ex-slaves’ past lives, as well as the level of ignorance in which they had been maintained, is countered by their hope for the future.

Transcript

The following extracts from letters recently received embody such information as can be gleaned from them for the benefit of our friends at a distance. — E. C. Collins, Secretary

December 24th 1864

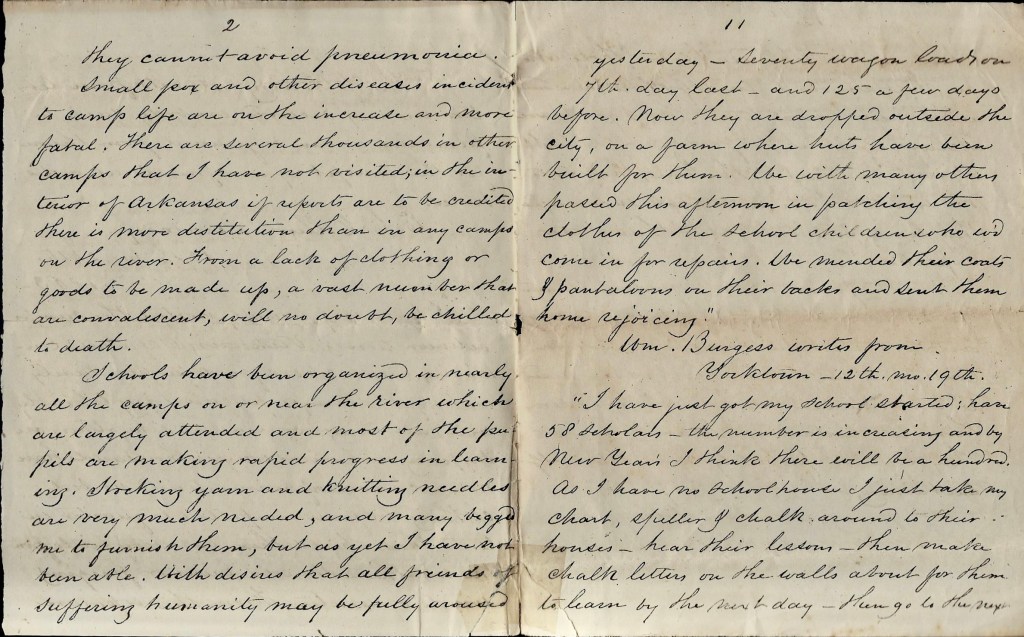

“I have very recently visited the camps between here & Vicksburg (12 in all) containing about 26000 freed people. Nearly one half of these people are doing tolerably well, all things considered. The others are suffering in various ways; thousands have not a change of raiment and no bed clothing and are compelled to quarter in tents that shield them but very little from the weather—the cold rains and freezing winds of winter. From this exposure they cannot avoid pneumonia, small pox and other diseases incident to camp life are on the increase and more fatal. There are several thousands in other camps that I have not visited; in the interior of Arkansas if reports are to be credited, there is more destitution than in any camps on the river. From a lack of clothing or goods to be made up, a vast number that are convalescent, will no doubt, be chilled to death.

Schools have been organized in nearly all the camps on or near the river which are largely attended and most of the pupils are making rapid progress in learning. Stocking, yarn and knitting needles are very much needed, and many begged me to furnish them, but as yet I have not been able. With desires that all friends of suffering humanity may be fully aroused to a sense of duty and immediate action, I conclude for want of time to add more.” – Elkanah Beard, Memphis, Tennessee

[Note: the Elkanah Beard letter was published in full in the Friends Review of 23 January 1864, pp. 323-324.]

Helena, 1

“The condition of this camp is far from satisfactory though superintendent Kenick is doing all that he can to improve it. The visit to it was a very sad one, and I longed for a supply of clothing at once to relieve the needs of the poor creatures who in many cases had but one garment and were suffering from cold and disease. There is a peculiar dampness in the atmosphere which makes the cold hard to bear. The number of colored people here during the past year has been some 4,000. There have [been] 1,100 deaths. This statement tells the story. They want underclothes and children’s clothing. Garments for the men are not needed as they have the clothing of deceased soldiers which they use for outside garments. In one case I saw a sick woman in bed who had nothing but a blanket in which she rolled herself. Children’s shoes are very badly needed here. I think almost the best thing we could do would be to send some shoemaker’s tools and several sizes of lasts for women and children with suitable thread. They can get leather here and there are several shoemakers among them who understand how to use the tools.”

— Samuel Shipley

1 In May 1863, a Quaker man named Levi Coffin visited Helena, where he met with an old neighbor, William Shugart. Coffin wrote that he found 3,600 contrabands in Helena working either in the service of the government or as farmers. Many blacks were living in three large churches, while others found shelter in houses and in tents. Coffin referred to other camps between Helena and Vicksburg, Mississippi, among them Camp Deliverance, Camp Wood, and Camp Colony. However, shortly after Coffin’s visit, these camps were attacked by the Confederates, and many blacks perished in the burning cabins in which they were housed.

2nd letter from S. Shipley, dated Vicksburg

Vicksburg represents a number of camps. The general superintendents of the Western & Southwestern camps is Col. John Eaton. He is one of nature’s noblemen. Happy are these oppressed people that they have found such an advocate & defender. He strongly advises us to send out an agent who understands farming. He expressed much satisfaction in the labors of the Friends—says that all we can do will be needed; that the work is colossal. There are two schools here with 500 scholars and 20 teachers. Some classes are taught by soldiers. 30 learned to read in 8 weeks. Clothing is hard to procure; calico sells for 50 cents per yard. A tin basin for $1, and all other things in proportion. The greatest trouble is in the camps outside of the city limits. I rode on horseback to Blake’s Plantation; 2 though the superintendent, Capt. Elliott, is doing all he can, there is great suffering there. About 1,600 are in two camps. In my walks there through the quarters, I found many poor creatures wornout with long years of suffering & privation, some of them now over 75 years old, on beds of sickness with scarcely clothing to cover them. You would be deeply moved to hear them thank their Heavenly Father for the great boon of Freedom and express themselves satisfied that He could care for them. No tongue can tell what they have suffered. I authorized Capt. Elliott to buy two stoves for a large room in the second story of a barn hitherto unused because it could not be warmed. He proposes to use this room as a hospital. I shall direct E[lkanah] Beard to supply this camp with clothing. There are numerous camps of which we hear little or nothing.”

2 See Letter No. 5, 1863-64: THURLOW JOSEPH WRIGHT TO CAROLINE S. WRIGHT describing Blake’s Plantion; “[Benson Heighe] Blake Plantation about ten miles from Vicksburg on the Valley Road. The husband of Mrs. Blake is a colonel in the rebel army. She is living on the plantation and depends upon the government for rations. The Blake’s Plantation are three in number which contain many thousands of acres of as fine land as the sun ever shone upon. She is, I am informed, strong in the faith still. Yet a visible improvement has taken place in her made from the remark, I am told she has frequently made—that is, that she does not care which government is successful, ours or the Southern Confederacy so that the property she and her husband once owned could be placed in her possession as it once was. She is after the dollars and the negroes could she hold them.”; See also excerpts of Memoirs of Louisa Russell Conner who wrote: “[The Yankee] army was followed by hundreds of negroes and they formed these contrabands as they were called into camps or corrals. One of these corrals was on each of Mr. Blake’s plantations the one at Blakely being probably the largest as the accomodations [sic] were greater. There were seventeen hundred in this corral stored away in the quarters, in tents and in the gin to which they built two stories…. Very soon Yankee school teachers or ‘Marms’ as they were called arrived and took up their quarters in the corral to teach the negroes. The whole field presented a singular appearance dotted with camps, etc. and standing out in the sun and rain were carriages of various kinds which were brought there by the Yankees or negroes.”

A letter from T. Nicholson dated December 30th [1863] says—

“More suffering exists in Tennessee & in Alabama & interior of Arkansas than any other points. It is very satisfactory to know that the agents employed appear to do their best. Col. Eaton says that the great necessity centers at Pine Bluff, Vicksburg, & Natchez.

At one point where 100 orphan children are collected a request was made for needles & yarn. It is a great satisfaction to know that the Young Men’s Aid has sent out both needles and yarn to meet this want, & that they have also dispatched lasts, with shoemakers findings for the camp indicated by Samuel Shipley where shoes were so much wanted.

From Newbern, N. C. where so much distress from small pox 3 has prevailed, the letter from Helen James (the wife of the Superintendent) states, “I am happy to announce the arrival of your valuable box. A part of the contents have already been distributed to meet the requisitions made upon me by the orders from the small pox hospitals. These are given to patients about to be discharged & are all they have to begin the world with, as every particle of clothing & bedding possessed by those poor creatures is burned.”

3 John Williams, an African-American soldier in New Bern, N.C., supplied more chilling detail in an 1864 letter to a Union officer outlining the disparity in treatment of white and black victims: “I write to know if theire cant be some protection for the colored people of new Bern the people of coler when they are taken with the small pox they hae to be dragged across the river and their they have not half medical attendanc for them. It is said by the folks that has got well that they do not get enough to eat and when thy die thy have a hole dug and put them in without any coffin and I think this is a most horrible treatment and therefore thy ought to have some person that will look after them in a better manner then this[.] the[re] is A grat distinction made between the white and the colored in such cases as this when the whites are taken with this disseas thy taken care of and so you will pease to look into this matter.” [Source: Freed Slaves Battle Small Pox and Other Diseases, by Jim Downs]

From Norfolk—Lucy Chase 4 writes on December 23, 1863—

“I am fresh from an hour or two at the jail yard where 130 refugees are looking into the future. They came in yesterday, brought from their masters by Col. Wild’s Brigade. Smiling, hopeful, and satisfied they all are. “Don’t care if we are crowded”—“Would rather live on bread & water than stay in my old home.” You must all go to the schoolhouse tomorrow, I said. We will give you books and teach you & fit you to help yourselves.” “If I can find the way there, I reckon I shall be [ ] there myself,” said one sprightly mama. “I’ll go;” ”I’ll go” said several. I took with me a quantity of primers adn after exciting the ambition of the multitude, I took a slate and wrote copy for them, and plunged them deep into letters. A moment of instruction tests the ability & interest. Some of the very young boys and girls gave me undivided attention and learned rapidly. Others never knew the meaning of fixed attention and required constant urging. We have had many bunks built in the yard, have had the walls whitewashed, the broken window sashed, mended and an approach to comfort secured. Every new arrival is more marked in interest than any preceding one; as the multitude crowded around me this morning, losing their heads in the folds of my shawl, looking into my face with faith and thanksgiving, crowding the stairway, grouping themselves into families, as it were instinctively, on the approach of a stranger, the scene was picturesque in the extreme. Seeing but little baggage, I enquired if they were obliged to leave it behind. “We couldn’t bring anymore honey.” … 18th—Today 125 wagon loads of negroes came into Portsmouth & will probably be here tomorrow. Sarah & I spent this afternoon in the yard giving necessary clothing to a few of the most needy and remembering the many on their way, husbanding our resources. 23rd—300 more refugees came yesterday—seventy wagon loads on 7th day last—and 125 a few days before. Now they are dropped outside the city on a farm where huts have been built for them. We with many others passed this afternoon in patching the clothes of the school children who would come in for repairs. We mended their coats and pantaloons on their backs and sent them home rejoicing.”

4 “When Lucy Chase (1822-1909) and her sister, Sarah Chase (1836-1911), single women from a well-to-do Quaker family of Worcester, Massachusetts, arrived at the contraband camp established on Craney Island near Norfolk, Virginia, in 1863, they found the needs of the newly freed slaves assembled there to be overwhelming. They commenced their work of dispensing material aid, establishing schools, and preparing black people to become self-sufficient, work they continued in other locations in the South for much of the decade. The correspondence of the Chase sisters, which spans the years 1861-70 and includes a number of letters from New England supporters and blacks whom the sisters had taught, constitutes a valuable source for examining the interaction of female humanitarians from the north with federal officials, ex-slaves, and white southerners. Lucy Chases’s richly detailed accounts of the life histories of former slaves and the beliefs and religious practices of the black community are of unusual interest.” [See Dear Ones at Home; Letters from Contraband Camps“

William Burgess 5 writes from Yorktown, December 19th [1863]—

“I have just got my school started; have 58 scholars—the number is increasing and by New Years I think there will be a hundred. As I have no schoolhouse, I just take my chart, speller & chalk around to their houses—hear their lessons—then make chalk letters on the walls about for them to learn by the next day. Then go to the next house and do likewise & so on. Those who are most anxious to learn follow me around and so recite several times. As i go, I have a class of about half a dozen of the brightest with me most of the time; that suits me exactly. I am very much encouraged. They learn so much faster than I ever expected.”

On the farms in the Department around Fortress Monroe, Norfolk, etc. comprising over 5,000 acres, two thousand hands are constantly employed—the produce raised is very valuable & does much to render them self sustaining. In another year they will be probably more than self-sustaining.

5 William H. Burgess, a Quaker, was drafted as a soldier but was released when he offered his services to labor amongst the Contraband refugees as a school teacher at Yorktown. He was supplied with clothing, shoes, leather and shoemakers’ tools, school-books, Bibles, Testaments, etc. to distribute to the refugees by the Friends Society. [See Report of the Executive Board of the Friends’ Association of Philadelphia and Its Vicinity, for the Relief of Colored Freedmen”]

I have read extensively on the Civil War and read little of this.

LikeLike