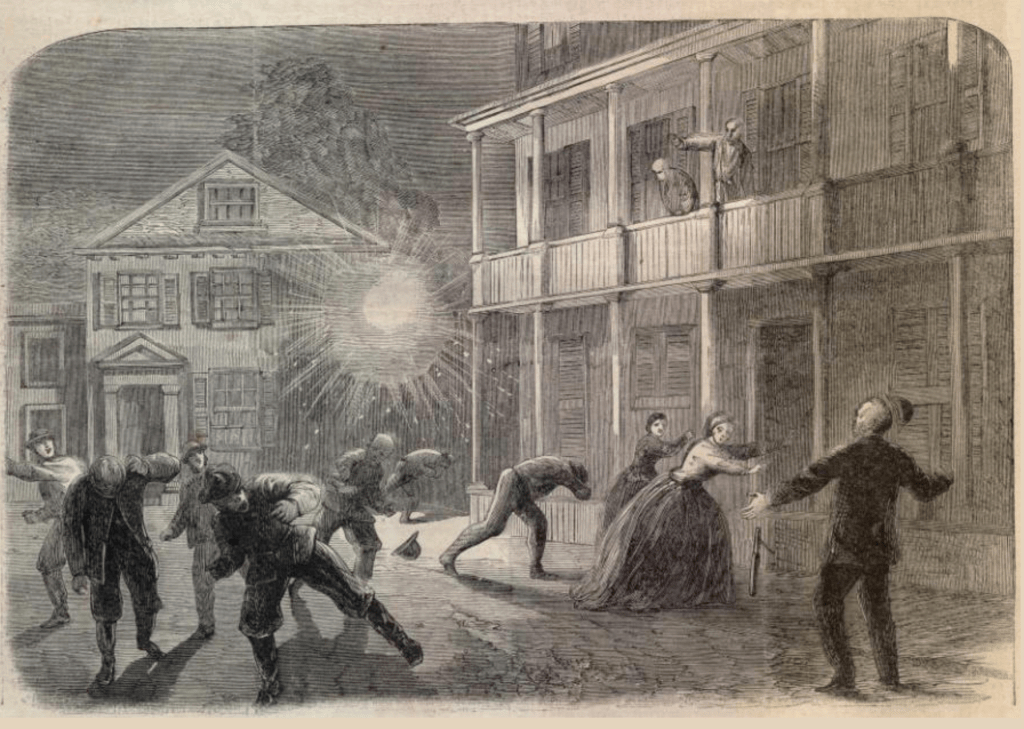

After several unsuccessful attempts to take Charleston by water, the Union launched a different tactic—shelling Charleston civilians from James and Morris Islands. Gillmore set twenty-two thousand men to work erecting gun batteries in the island marshes facing the Charleston peninsula and Fort Sumter. The batteries were five miles from the city, too distant for conventional ordnance to reach, so residents were at first unconcerned. However, recent weapon developments and rifling technology actually put the city in range, and on the night of August 22, 1863, the “Swamp Angel” gun opened fire on Charleston.

The first shell hit Hayne Street near the Market, narrowly missing the Charleston Hotel. A British visitor recalled, “At first I thought a meteor had fallen, but another awful rush and whir right over the hotel and another explosion beyond, settled any doubts that the city was being shelled.” Beauregard admonished Gillmore: “It would appear sir, that despairing of reducing our works, you now resort to the novel measure of turning your guns against old men, the women and children, and the hospitals of a sleeping city, an act of inexcusable barbarity.” Church steeples became targets for Union artillery, so many closed during the siege for the safety of their parishioners. Newspapers reported that many residents had made a “Grand Skedaddle,” leaving as quickly as they could pack their belongings.

Those who stayed became used to the daily explosions. Fitz Ross, a visiting journalist, wrote, “Nine out of ten shells fall harmless—the hope of the Yankees to set fire to the city or batter it down have hitherto proved disappointing.” The shelling continued with varying degrees of intensity for 587 consecutive days. In January 1864 the Charleston Mercury did report a frightening near miss: “One of the enemy’s large shells, after penetrating the roof of a dwelling, overturned a bed in which three young children were sleeping, throwing them rudely on the floor, but then strange to say, it passed without bursting, and buried itself in the foundation of the house.”

The worst bout of shelling occurred during a nine-day stretch in 1864, when over fifteen hundred shells rained down on the city. Volunteer fireman Charles Rogers wrote to his wife in June 1864 that “there was a fire downtown last week, and the Yanks dropped their shells in town like peas…I have experienced a remarkable change since my return. In fact it is a matter of much congratulation in the Starvation times. I don’t eat half as much now.” [Source: Christina Rae Butler, Legends Magazine]

I can’t be certain of the identity of the “S. S. Roberts” who wrote this letter but I believe it to have been 30 year-old Stephen S. Roberts (b. 1834) who worked as a clerk in Charleston and whose widowed mother Mary Roberts lived on Spring Street east of King Street in the City. Though he called himself “Old Woman,” I think this was in jest. The letter was datelined from Summerville where many residents fled to avoid the shelling.

The letter was written to William Birnie (1782-1865), a Charleston, S.C., merchant and president of the Bank of South Carolina. It may have been that Roberts clerked for Birnie. William Birnie was an immigrant from Aberdeen, Scotland, who had settled in Charleston in the 1850s. Birnie refugeed to Greenville during the Civil War, and in October 1863 purchased 96 acres and a home on the Augusta Road for $30,000 that became his home.

Charleston remained under intermittent bombardment from August 1863 until it was evacuated in February 1865. Though only five individuals would be killed by the cannonade, Charlestonians moved north of Calhoun Street and along the Ashley River. The downtown area became known as the “Shell District.” The historic churches, houses, and graveyards were damaged and some destroyed by Union shells.

Transcription

Summerville, [South Carolina]

17th January 1864

Wm. Birnie, Esq.

Respected sir, it has been some time since I wrote you last and there has been many changes in our good old city since then. I removed Mr. Ogilvie’s 1 stock up Meeting Street after I found Broad Street had been completely deserted by everybody else. A great many removed to the south of Calhoun Street which I remarked at the time was very foolish of them. Friday’s shelling will tell them that they will be compelled to make another move higher up.

Last Friday the Yanks threw a shell into Charlotte Street & another in John Street east of Meeting Street. What a stampede these two devils have caused amongst the people. The Banks & portions of the Government departments removed by daylight Saturday morning. The Bank of Charleston had pulled up stakes & gone—where to? deponent knoweth not. Sub Treasury & most of the other banks were removing yesterday afternoon.

I do hope that the Yanks may never reach my new quarters. On Thursday last the enemy put a shell through the shed of our old store which did not stop until he reached the second floor. There the gentleman belched out all his venom & made sad havoc all around. The lower story not injured farther than the contraction of the doors attached to the large safe, or in other words—vault. Not many panes of glasses to be seen over the building. To my astonishment, there is not one piece of the shell to be found in the rooms. I notice several holes in the walls so I suppose the fragments have hid themselves in them. The building is not as badly damaged as I expected to find it.

The Southwestern Railroad Bank was also struck and received much more injury than your building. Yesterday when I was down in Broad Street, the shells came whistling over my head like so many Mock Birds. Any number struck around the neighborhood. When leaving the old establishment, I took a farewell look at the old place & said to myself, “Old woman, this will be the last visit I will pay you until our esteemed friends shall stop sending so many black pills to yourself & neighbors, as I have no relish for those sort of plums.”

I have heard heavy firing all last night & this morning. My health & my mother’s not of the best. I hope this will find yourself & family well. Please accept for yourself & Mrs. B. our best respects. I remain, dear sir, truly — S. S. Roberts

1 William Matthew Ogilvie (1810-1872), a native of Scotland, married Margaret Murdock Walker in Charleston in 1840 and was a merchant in Charleston at the time of the Civil War.