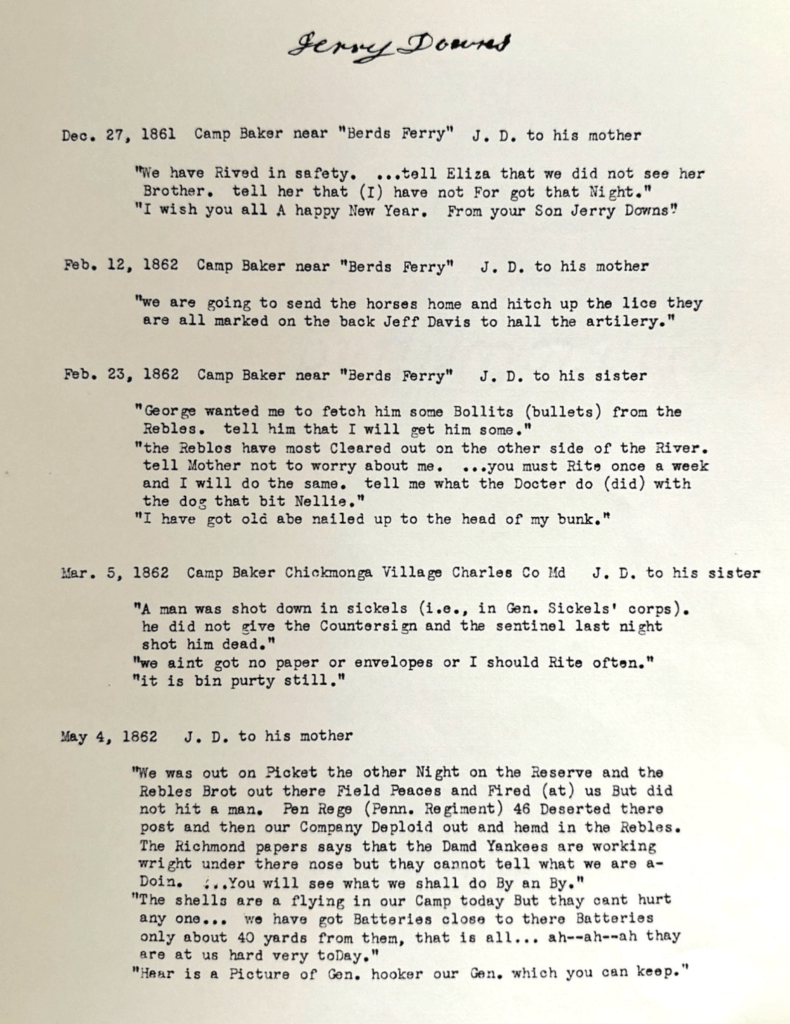

“I have got old abe nailed up to the head of my Bunk,”—the title of a brief biographical sketch of Pvt. Jeremiah Downs prepared by historian Patrick Leary decades ago after perusing and taking notes on eight of Jeremiah’s war time letters. Leary’s sketch reads:

Pvt . Jeremiah Downs

A self-described “mariner” from Newburyport, Mass., Jerry Downs enlisted in the Eleventh Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry on November 1, 1861, aged 25. Barely three months before, the “Boston Volunteers”—as the regiment was locally known—had lost 8 men at the first Battle of Bull Run, where Union forces had been ignominiously routed. After spending the winter of 1861-62 on picket duty along the Potomac south of Washington, the regiment moved south to join the forces being gathered under General McClellan at Fortress Monroe on the tip of the peninsula formed by the James and York Rivers. McClellan’s plan was to move up the peninsula with an overwhelming body of men and lay siege to Richmond, capturing the Confederate capital and ending the war in one bold stroke. Beginning the march on April 2, the Union army had got only twenty miles along when it was checked at Yorktown by a force of 13,000 men under Confederate General John B. Magruder. By skillfully deceiving McClellan as to the size of the city’s garrison, Magruder prompted his opponent to settle down for a careful siege, thus tying up the 53,000-strong Union forces for an entire month. On May 3, under command of the newly arrived General Johnston, the Rebels evacuated the city, pursued by the Yankees. After brisk skirmishing before Williamsburg on May 4—described by Private Downs in his letter of that date, written in the middle of the all-day artillery exchange—the Union divisions of Generals Hooker and Smith attacked the Confederate earthworks the following morning. Hooker’s division, of which the 11th Mass. was a part, was then attacked by a large force of Rebels; holding its position alone under constant fire for the rest of the day, the division was finally relieved by General Kearny’s division, after having suffered 1,700 casualties and the capture of five pieces of artillery.

After the Battle of Williamsburg, the Confederate forces moved northwest behind the Richmond defenses, while McClellan deployed his forces north and south of the Chickahominy, with his headquarters at West Point, at the head of the York River. Seeing the Union forces thus split, straddling the Chickahominy, Confederate General Johnston attacked the 19,000 Yankees south of the river at Fair Oaks with a Rebel force of 32,000 men. This battle—mentioned by Private Downs in his letter of July 24—lasted two days (May 31-June 1), ended in a draw after Union reinforcements arrived, and cost each side about 6,000 casualties. The rest of that remarkable letter describes in graphic detail the Seven Days’ Battles—Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, Glendale, and Malvern Hill—in which Robert B. Lee’s army, beginning its attack on June 26, pushed the Union forces down the peninsula in a series of ferocious encounters that ended with McClellan’s retreat to the fever-ridden marshes of Harrison’s Landing. Jerry Downs calls it, simply, the “hard times we had coming from Fair Oaks.” The particular battle he describes is probably Malvern Hill on July 1, where Union batteries and infantry repulsed wave after wave of Rebel charges. One of the most severe artillery barrages of the war left 5,000 Rebel dead and wounded lying on the slopes—“sawed ends out” like stacks of wood, in Downs’ painfully graphic phrase.

Jerry Downs was one of many Union soldiers of the Peninsula Campaign

to survive fierce combat unscratched only to be felled by malaria and dysentery at the Harrison’s Landing camp. He was eventually moved to the large Federal hospital at Alexandria near Washington; he was discharged from the army for disability on December 5, 1862, and returned home.”

Jeremiah Downs was the son of Jeremiah (b. ca. 1815) and Abigail L. Downs (b. ca. 1809). According to the 1850 Census, he had one brother, George (b. ca. 1840) and two sisters, Sarah Smith (b. ca. 1832) and Mary Colton (1827). It should be noted that there are other letters by Downs written while he was in the service. Several of his letters appear on Private Voices under Authored Letters although they are transcripts only.

Transcription

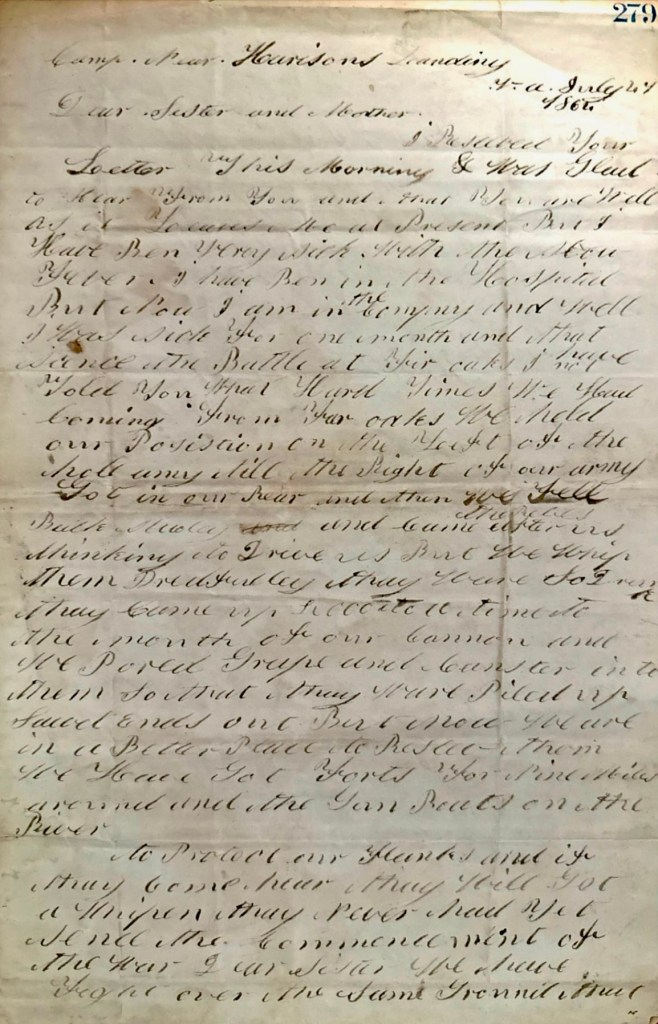

Camp near Harrison’s Landing, Va.

July 24th 1862

Dear sister and mother,

I received your letter this morning & was glad to hear from you and that you are well as it leaves me at present. But I have been very sick with the slow fever. I have been in the hospital but now I am in the company and well. I was sick for one month and that since the Battle at Fair Oaks. I have not told you what hard times we had coming from Fair Oaks. We had our position on the left of the whole army till the right of our army got in our rear and then we fell back slowly and the Rebs came after us thinking to drive us, but we whipped them dreadfully. They were so drunk, they came up 1,000 at a time to the mouth of our cannon and we poured grape and canister into them that they were piled up sawed ends out. But now we are in a better place to receive them. We have got forts for nine miles around and the gunboats on the river to protect our flanks and if they come here, they will get a whipping [like] they never had yet since the commencement of the war.

Dear sister, we have fought over the same ground that our forefathers fought and the forts are still here that they made. President Harrison’s house is on the James River where we camped the first day we got here. It has a beautiful view up and down the river, is the house that [Edmund] Ruffin lives in—the first man that fired the first gun against Fort Sumter.

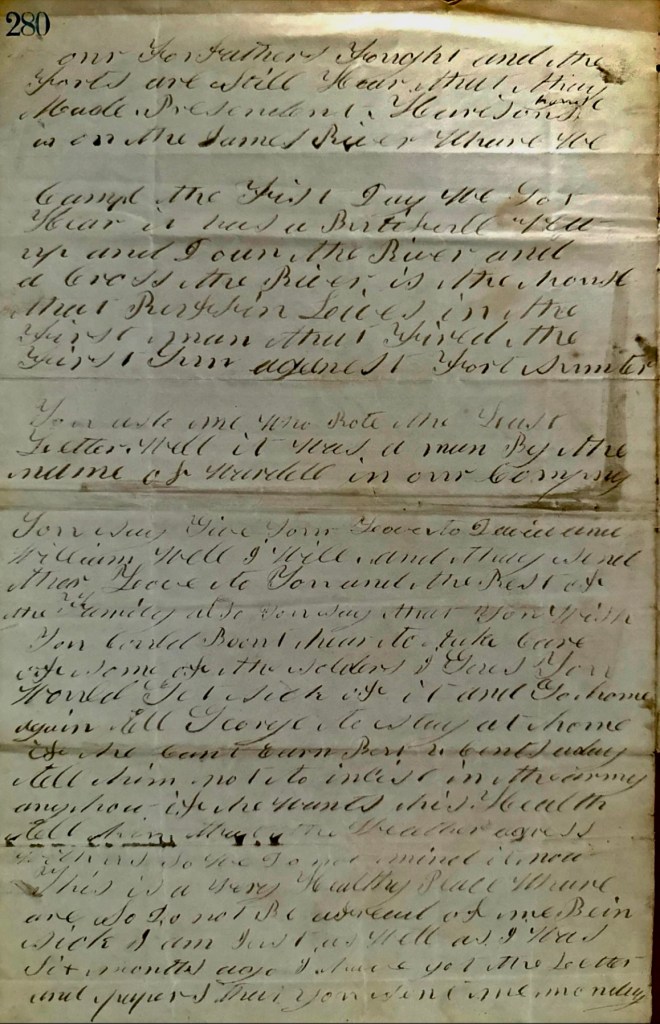

You ask me who wrote the last letter. Well, it was a man by the name of Wordell in our company.

You say give your love to David and William. Well, I will, and they send their love to you and the rest of the family. Also you say that you wish you coulda been here to take care of some of the soldiers. 1 I guess you would get sick of it and go home again. Tell George to stay at home if he can’t earn but 4 cents a day. Tell him not to enlist in the army anyhow if he wants his health. Tell him that the weather agrees with us so we do not mind it now. This is a very healthy place where we are so do not be worried of me being sick. I am just as well as I was six months ago. I have got the letter and paper that you sent me Monday. When you send the box, put anything in that you have a mind to. Please do put in a salt fish and some whiskey.

The directions to send:

Company D, 11th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers. Fortress Monroe, Va.

Harrison’s Landing

Hookers Division

Ask the expressman to be sure. That is all that I can think [of] now. I will close. Give my love to all. Goodbye. Write soon. From your brother, — Jeremy Downs

1 Jeremiah’s sister, Sarah E. (Downs) Smith volunteered her services as a nurse during the Civil War. She began her nursing early in 1862. Her husband, George, had died in 1854 in St. Thomas, so at 32 yeas of age and a widow, she was readily accepted into the nursing corps. She became a matron in the Trinity Church Hospital in Washington D. C. She eventually died of tuberculosis at the age of 42 which she probably contracted during the war.

Notes from Patrick Leary’s perusal of all eight of Downs’ letters.