The following remarkable letters were written by Helen Louise Gilson, a native of Boston, but raised in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Her parents, Asa Gilson (1772-1835) and Lydia Cutter (1775-1838) died when Helen was but a little girl. She was the niece of the Honorable Frank Brigham Fay, former Mayor of Chelsea, and she was his ward. Helen wrote all of these letters to her older sister, Mary Ann (Gilson) Holmes (1824-1906), the wife of Galen Holmes, Jr. (1813-1892) of Boston. Their children were Helen (“Nellie”),b. 1850; Carrie, b. 1853; Galen Franklin (“Frank”), b. 1856; and Marian, b. 1859.

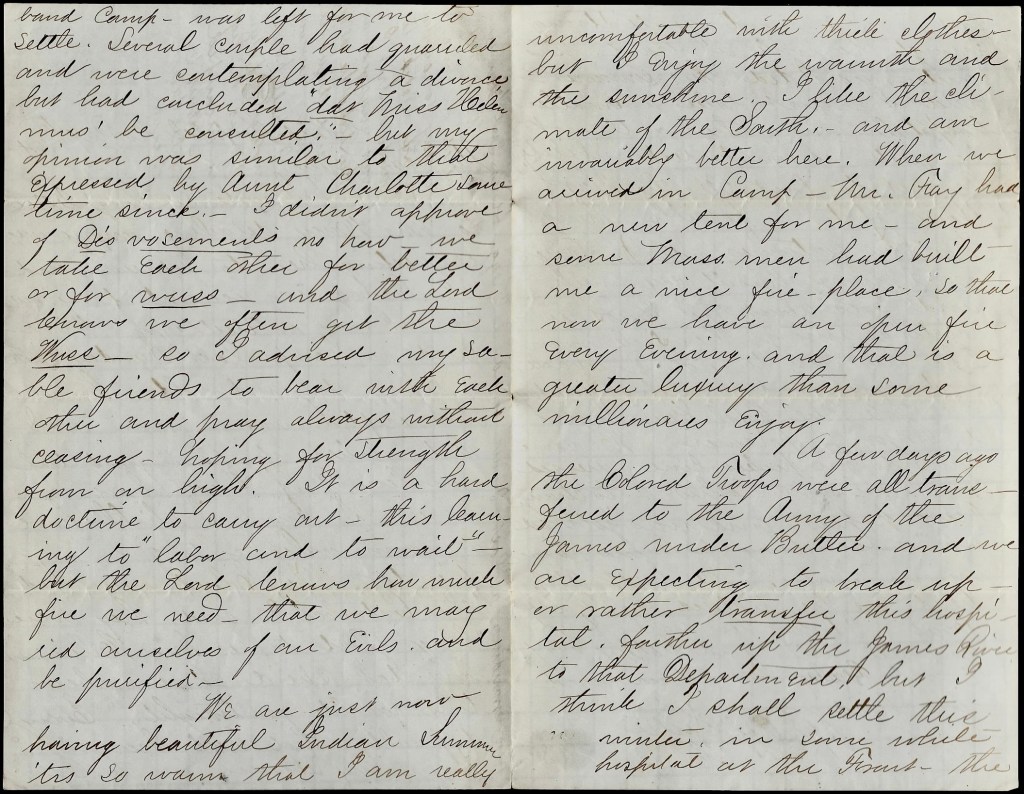

Mr. Fay took an active interest in the Union cause during the Civil War, devoting his time, his wealth and his personal efforts to the welfare of the soldiers. Beginning in the autumn of 1861, Gilson’s uncle Frank Fay went in person to every battle in which the Army of the Potomac fought. He went promptly to the battlefield and moved gently among the dead and wounded, soothing those who were parched with fever, crazed with thirst, or lying neglected in the last agonies of death.

Helen Gilson was greatly influenced by her uncle’s selfless work and wanted to assist him. She applied to Dorothea Dix, the Superintendent of Female Nurses. She was rejected because she was too young, but that did not prevent her from fulfilling her desire to minister to the sick and wounded. Gilson was allowed to work directly with her uncle and his assistants. They had their own tent, formed a tight-knit group, and even created something of a home life. She was present at almost every great battle of the Army of the Potomac, except the first Battle of Bull Run.

In the summer of 1862, Gilson was for some time attached to the Hospital Transport Service, and was on board the ship Knickerbocker at White House and at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, during the severe battles of McClellan’s movement from the Chickahominy to the James River, called the Peninsula Campaign.

When not more actively employed, she sat by the bedsides of the suffering men. She sang for them and knelt beside their beds amid all the agonizing sights and sounds of the hospital wards. She exerted a remarkable influence over the wounded soldiers. The United States Sanitary Commission had been established in 1861 to care for sick and wounded soldiers, but they had no field agents, and did not attempt to care for the wounded until they were brought to the field hospitals.

In 1863, Mr. Fay took to the Sanitary Commission his plans for an Auxiliary Relief Corps, which would give personal relief to the wounded soldier in the field, and to help him bear his suffering until he could be seen by a surgeon or be transferred to a hospital. For less serious wounds, the Corps would furnish the necessary dressings and attention. The Sanitary Commission adopted these plans, and made Mr. Fay chief of the Auxiliary Relief Corps. He served in that capacity until December 1864, when he resigned, but he continued his independent work until the war ended. Helen Gilson collected supplies and arranged for the transportation of wounded soldiers. She obtained a contract from the government to make army clothing, and kept soldiers’ wives and daughters busy raising money so she could attract more workers by paying a better wage than other contractors.

Gilson always shrank from publicity in regard to her work, but thousands witnessed her ability to evoke order out of chaos, and providing for thousands of sick and wounded men where most people would have been completely overwhelmed. From the reports of the Sanitary Commission, the following passage refers to her:

“Upon Miss Gilson’s services, we scarcely dare trust ourselves to comment. Upon her experience we relied for counsel, and it was chiefly due to her advice and efforts that the work in our hospital went on so successfully. Always quiet, self-possessed and prompt in the discharge of duty, she accomplished more than anyone else could for the relief of the wounded, besides being a constant example and embodiment of earnestness for all. Her ministrations were always grateful to the wounded men, who devotedly loved her for her self-sacrificing spirit. Said one of the Fifth New Jersey in our hearing, “There isn’t a man in our regiment who wouldn’t lay down his life for Miss Gilson.”

But Gilson’s crowning work was performed during the last series of battles in the war, the Overland Campaign. Fought entirely in Virginia, from the Battle of the Wilderness to Spotsylvania Court House to Cold Harbor to Petersburg to Appomattox, this campaign was marked by almost a year of constant fighting, and ended the most destructive war of modern times. Gilson took the field with Mr. Fay at the beginning of the campaign, and was tireless in her efforts to relieve the suffering caused by those horrible battles in May of 1864, in which the dead and wounded were numbered by scores of thousands.

Not until the battles of June 15 through June 18 of 1864 had there been any considerable number of the colored troops among the wounded of Army of the Potomac. In those engagements and the actions immediately around Petersburg, they suffered terribly. The wounded were brought rapidly to City Point, where a temporary hospital had been provided.

“It was, in no other sense a hospital, than that it was a depot for wounded men. There were defective management and chaotic confusion. The men were neglected, the hospital organization was imperfect, and the mortality was in consequence frightfully large. Their condition was horrible. The severity of the campaign in a malarious country had prostrated many with fevers, and typhoid, in its most malignant forms, was raging with increasing fatality.

These stories of suffering reached Miss Gilson at a moment when the previous labors of the campaign had nearly exhausted her strength; but her duty seemed plain. There were no volunteers for the emergency, and she prepared to go. Her friends declared that she could not survive it; but replying that she could not die in a cause more sacred, she started out alone.

A hospital was to be created, and this required all the tact, finesse and diplomacy of which a woman is capable. Official prejudice and professional pride was to be met and overcome. A new policy was to be introduced, and it was to be done without seeming to interfere. Her doctrine and practice always were instant, silent, and cheerful obedience to medical and disciplinary orders, without any qualification whatever; and by this she overcame the natural sensitiveness of the medical authorities.

A hospital kitchen was to be organized upon her method of special diet; nurses were to learn her way, and be educated to their duties; while cleanliness, order, system, were to be enforced in the daily routine. Moving quietly on with her work of renovation, she took the responsibility of all changes that became necessary; and such harmony prevailed in the camp that her policy was vindicated as time rolled on.

The rate of mortality was lessened, and the hospital was soon considered the best in the department. This was accomplished by a tact and energy which sought no praise, but modestly veiled themselves behind the orders of officials. The management of her kitchen was like the ticking of a clock—regular discipline, gentle firmness, and sweet temper always. The diet for the men was changed three times a day; and it was her aim to cater as far as possible to the appetites of individual men.

Her daily rounds in the wards brought her into personal intercourse with every patient, and she knew his special need. At one time, when nine hundred men were supplied from her kitchen (with seven hundred rations daily), I took down her diet list for one dinner, and give it here in a note, to show the variety of the articles, and her careful consideration of the condition of separate men.”

Through all the war, from the Seven Days’ conflict on the Peninsula in those early July days of 1862, through the campaigns of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and the fierce battles that were fought for the possession of Richmond and Petersburg in 1864 and 1865, Helen Gilson labored on until the end.

Through scorching heat and bitter cold, in the tent or on the open field, in the ambulance or in the saddle, through rain and snow, under fire on the battlefield, or in the more insidious dangers of contagion, she worked quietly, doing her part with all womanly tact and skill, until she finally rested, with the sense of a noble work done, and with the blessings and prayers of the thousands whose sufferings she has relieved, or whose lives she has saved.

As was the case with nearly every woman who cared for the sick and wounded, Helen Gilson suffered from malarious fever. As often as possible, she went home for a short time to rest and regain her strength, and it was those brief intervals of rest that enabled her to remain at her post until several months after General Lee’s surrender ended the war.

Helen Louise Gilson finally left Richmond in July 1865, and spent the remainder of the summer at a quiet retreat on Long Island, where she partially recovered her impaired health. In the autumn, she returned to her home in Chelsea, Massachusetts.

SOURCE: Woman’s Work in the Civil War

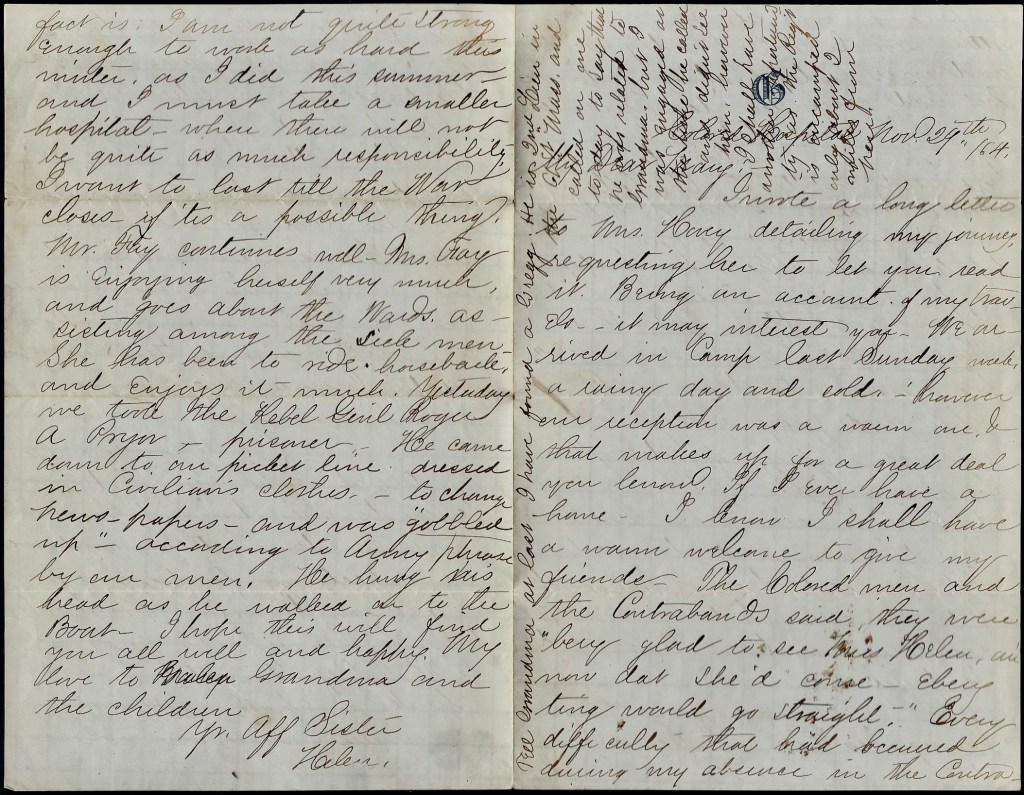

Letter 1

[Letterhead—US Sanitary Commission, Adams’ House, 244 F Street

Washington D. C.]

November 18th 1862

My drew Little Chickadee—dees. I call you chicks because when I come to see you, you run like little chicks to their mother. I want to see you all very much for I work very hard and do not see many little children. I think every night that I wish I could hold you on my knees and talk to you and tickle you, but then I have only two knees and there are four children. I tell you how I should manage. I should hold Nellie and Carrie and then I should take Frank and Marian, if baby would come. Do not forget to sing your little songs—especially “the Ark.” You must learn some new ones so as to sing to me when I come home. I hope you are very good little children and do not quarrel. You must mind mother always the first time she speaks.

The other day your Aunt Tiny was riding in a wagon to find some sick soldiers when the naughty Rebels fired some brawny guns and killed two men very near to me, but your Aunt Tiny was not hurt and you know who took care of her and kept her from all harm. It was our dear Heavenly Father who loves us—-how much He loves us. We ought to be very good.

Carrie must write again. The letters were very neatly printed. Mother and Father must not help you or correct any mistakes. Now goodbye little children. Give my love to Grandma and Mother & Father. From your Aunt Tiny

Letter 2

[US Sanitary Commission Letterhead, Washington D. C.]

April 15, 1864

Dear Mary,

I was very glad to get yours of April 7th although going to the ARmy it dd not reach me till yesterday as I came up from the Army on Tuesday last. Mr. Fay is still at the Front and will probably come up tomorrow. Then I shall be able to decide upon some course for myself. All ladies have been ordered away with much other extra baggage from the Army [of the] Potomac. It alters my plans materially and I am very much disappointed, I can assure you, but a few women have made trouble and the innocent must suffer with the guilty. There is a good field for labor among the Paroled Prisoners at Annapolis. Also I have had a call to go to Louisville, Kentucky but at present I am in chaos.

I received a most beautiful present of a diamond ring worth $110 and a Pearl Cross $100 the day before I came away. You can imagine I was delighted because it came from patients and officers of Potomac Creek Hospital.

I am glad to hear that Grandma’s foot is better. Give my warmest regards to her. Her journey on Earth has been a weary one, but there’s rest for the weary in Heaven.

I am glad Galen is improving so fast. He has harder battles to fight than some, to be sure. But every heart has its evil to conquer and we must all fight our battles daily, from Cyrus Hanks up to Dr. Bellows, and we all need to look up to a Higher Power to help us.

I am glad you are not going to move for you all enjoy the garden so much and you may now hope to gather your strawberries with your own hand,

I will send my drawers soon so that you may go on with the, I am glad you called on Delia. She has been kindly remembered by her friends and seems very happy. Their means are very limited, however, and they will have to economize. But Leander is enterprising and bound to get ahead. That is a good deal and while he tries to help himself, Mr. Fay will help him. Write me soon. Love to all the children and to Carrie. Very truly and affectionately your sister, — Helen

Letter 3

On Board Steamer Kent. off Port Royal

[May] 1864

Dear Sister,

It is a long time since you have heard from me. Indeed, I have had no time for many letters until now that we are on board this steamer where we can breathe a spell. Our wounded are all removed from Frederickburg and today we leave this place for White House Landing—the scene of our old labors of two summers since. We left Fredericksburg Thursday, bringing down wounded and now we expect tonight to go to White House. Today I have been ashore with Prof. [John Potter] Marshall of Tuft’s College—Mr. Fay’s particular friend—and he has been making sketches of old buildings and beautiful scenery. You cannot imagine what a scene of confusion an Army Base is—wagons, mules, fresh troops, forage. barges and steamers throng the place and make a scene of great confusion, and yet with all this Army life, in twenty-four hours everything will have left and all will be quiet—not a sound to be heard in this lovely spot on the Rappahannock’s banks except the splash of the waves and the sighing of the breezes.

Our last wounded have gone off today from Port Royal and at present we are lying at the landing, just in sight of a whole boatload of Contrabands who are making themselves happy by departing to the land of Freedom.

We had a hard experience in Fredericksburg—never so hard, I believe. Mr. [William Alfred] Hovey was not able to come down, or rather was not able to stand the life, so he went home. I was sick two days after ten of hard days and nights too. I hope I shall not be so busy after this. We all seem to think that Grant will besiege Richmond and we hope it will be with but little bloodshed.

Give my love to Galen, Grandma and the little children, to Carrie, Gus, and little Meand. In this I shall send you $10 (ten) Boston money for the Drawers. It is coming summer and you will need it.

Affectionately your sister, — Helen

Letter 4

Colored Hospital, City Point, Va.

August 2nd 1864

Dear Mary,

Yours of the 27th came yesterday and I was glad to get it indeed. It is terribly hot here and we have plenty work. We had a number of wounded came in yesterday to the Colored Hospitals. The negroes made a charge the day before. They told lively stories of the undermining of that fort, describing the scene in glowing colors—of frying pans and tin plates filling the air. It seems they surprised the Rebs at breakfast. [see Battle of the Crater]

I have little news but no matter. If my letter don’t contain the news, you won’t care—if it is only a word from me. It looks as if City Point would be a base for some time to come and we must have hard fighting I think to gain the end. You keep me posted on all the news of your family and the Hollis’s I am glad Sarah has taken a vacation and hope she will be quite alone.

I hope you will, or have seen Mr. Fay. He said he should call on you. I expect him back tomorrow. Howie did finely at his examination, it seems, and his father and mother have reason to be proud. Mr. Fay as usual ascribes all the praise to me saying, after speaking at the Exhibition, “I think you would have been proud if you had been here and you have a right to be for you helped to make Howie what he is—I have done less and claim no credit.”

So you see he appreciates my labors in behalf of his children. I am glad Frank and Carrie did so well. I want them to be good scholars for the more highly educated one is, they better they can fill any station in life. I will not except, the humblest.

I believe I did not tell you I had a letter from Susan. She sent me photos of her children and house. I will enclose them and you may take care of them for me. She is well and says she has no hard feelings toward you, but didn’t suppose you cared about her. Now I want you to write her for there is no earthly reason why there should be any break in our family of three sisters and I shall never recognize any.

Now the mail closes. With love to all, old & young, I am affectionately your sister, — Helen

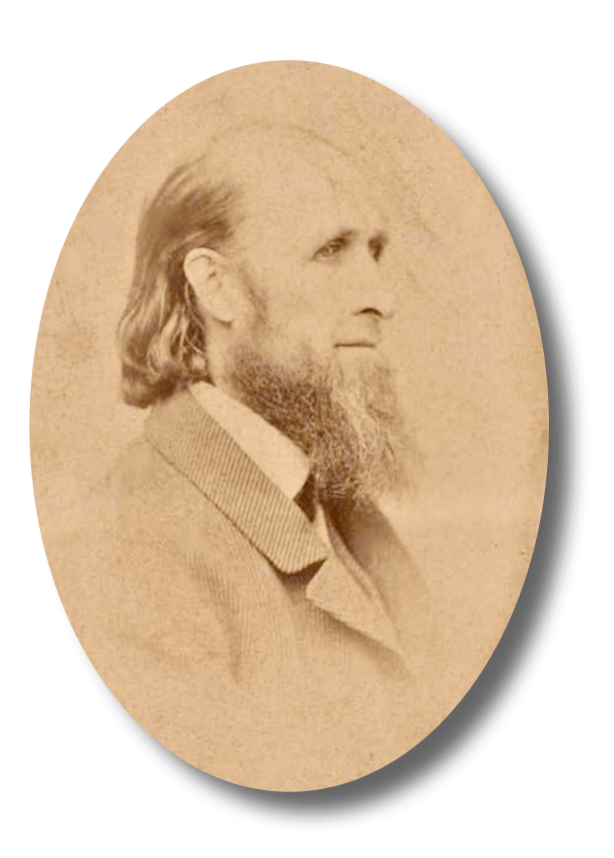

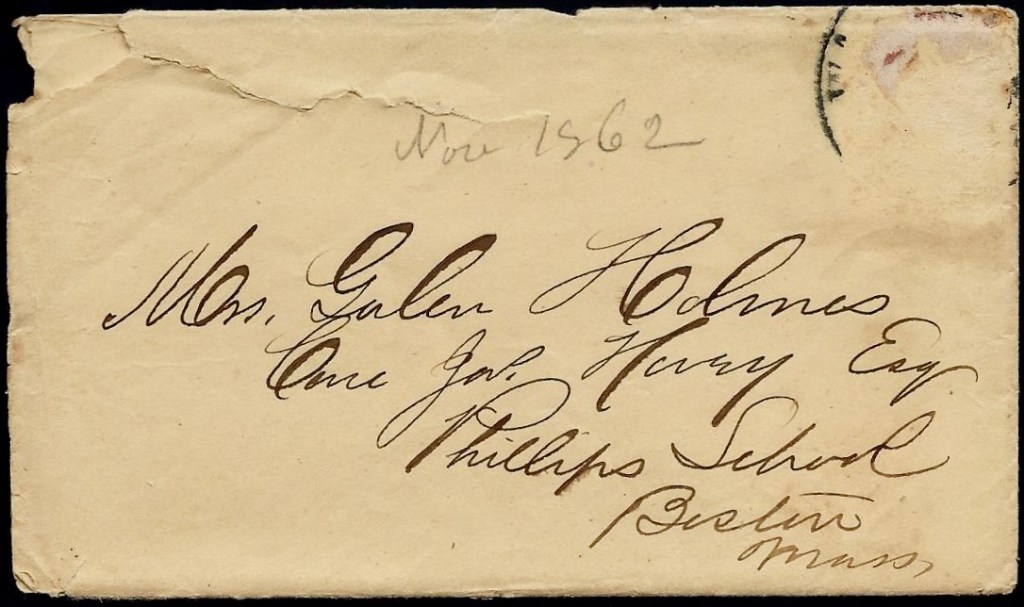

Letter 5

Colored Hospital

November 29, 1864

My dear Mary,

I wrote a long letter to Mrs. Hovey detailing my journey, requesting her to let you read it. Being an account of my travels—it may interest you. We arrived in Camp last Sunday week, a rainy day and cold. However, our reception was a warm one & that makes up for a great deal you know. If I ever have a home, I know I shall have a warm welcome to give my friends.

The Colored men and the Contrabands said they were “being glad to see Miss Helen and now day she’d come, ebery ting would go straight.” Every difficulty that had occurred during my absence in the contraband camp was left for me to settle. Several couples had quarreled and were contemplating a divorce but had concluded “dat Miss Helen mus’ be consulted” but my opinion was similar to that expressed by Aunt Charlotte some time since. I didn’t approve of Dis vosements no how. We take each other for better or for wuss, and the Lord knows we often get the Wuss—so I advised my sable friends to bear with each other and pray always without ceasing—hoping for strength from on high. It is a hard doctrine to carry out—this learning to “labor and to wait” but the Lord knows how much fire we need that we may rid ourselves of our Evils and be purified.

We are just now having beautiful Indian Summer. Tis so warm that I am really uncomfortable with thick clothes. But I enjoy the warmth and the sunshine. I like the climate of the South and am invariably better here. When we arrived in camp, Mr. Fay had a new tent for me—and some Massachusetts men had built me a nice fireplace so that now we have an open fire every evening and that is a greater luxury than some millionaires enjoy.

A few days ago the Colored Troops were all transferred to the Army of the James under Butler and we are expecting to break up or rather transfer this hospital farther up the James river to that Department, but I think I shall settle this winter in some white hospital ay the Front. The fact is, I am not quite strong enough to work as hard this winter as I did this summer and I must take a smaller hospital where there will not be quite as much responsibility. I want to last till the war closes—if tis a possible thing.

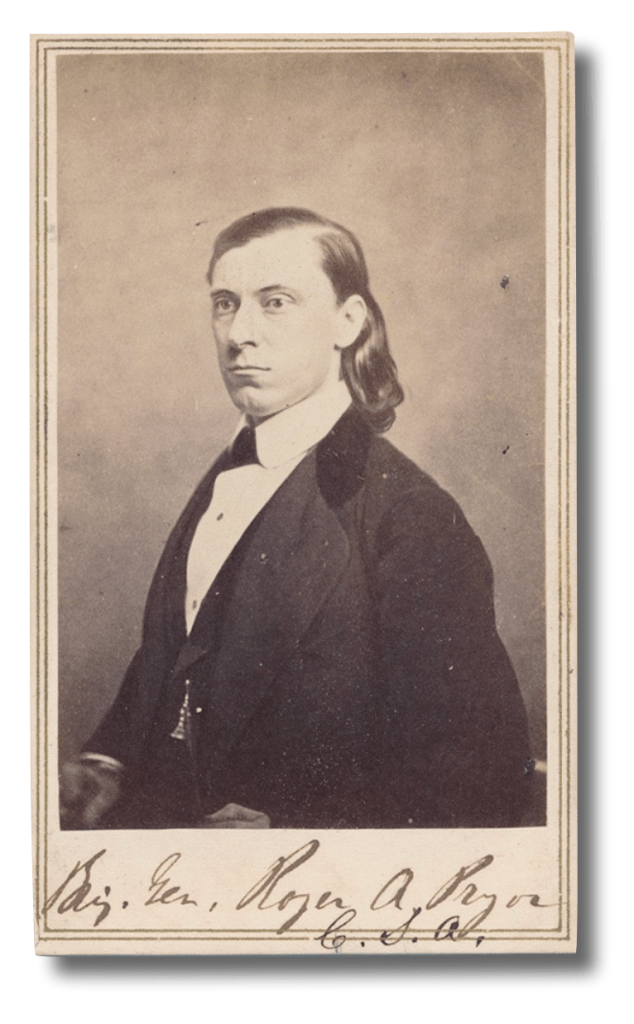

Mr. Fay continues well. Mrs. Fay is enjoying herself very much, and goes about the Wards assisting among the sick men. She has been to ride horseback and enjoys it much. Yesterday we took the Rebel General Roger A. Pryor prisoner. He came down to our picket line dressed in civilian’s clothes to change newspapers and was “gobbled up” according to Army phrase by our men. He hung his head as he walked onto the boat.

I hope this will find you all well and happy. My love to Grandma and the children. Your affectionate sister, — Helen

Tell Grandma at last I have found a Gregg. He is 2nd Lieutenant in the 61st Massachusetts and called on me today to say that he was related to Grandma but I was engaged at the time he called and didn’t see him. However, I shall have another opportunity as the regiment is encamped only about two miles from here.