This is an 1851 stampless folded letter (SFL) from Benjamin Grist, a barely literate slave overseer in rural southeastern North Carolina to his cousin, Allen Grist, a very wealthy (and much more educated) businessman and slaveowner (owning more than 100 slaves) then in Wilmington N. C. Benjamin writes his “cuzen”, (who was also the owner of the plantation on which Benjamin worked), to provide an update on his trials and tribulations in overseeing Allen’s vast ‘turpentine’ plantation (a major business in that part of NC at the time). Much of the letter deals with problems with some of the slaves, including running away and then having to be ‘punished’ after being caught and returned, e.g. ”I give tham 40 [lashes] a peas [apiece].”

The letter is postmarked Wilmington, N. C., but is datelined “St. Pauls,” N. C. It has a manuscript “Way 5” rate mark, meaning that, rather than being brought to the local post office, it was hand-carried to a mail carrier who had the city of Wilmington on his route.

The turpentine business of Benjamin and Allen Grist are covered extensively in the book “American Lucifers: The dark history of Artificial Light, 1750-1865”, published in 2020 by Univ. NC Press, and the winner of that year’s Beverige Award by the American Historical Association. The book covers the early southern turpentine industry—in particular the use (and abuse) of slaves who were the primary source of extracting the resin from pine trees (from which turpentine was distilled). In 1860, Grist was listed as owning $50,000 in real estate and $92,900 in personal property, including 109 slaves, making him the largest slaveholder in Beaufort County. A. & J. R. Grist, turpentine farmers, held $44,000 in real estate and $125,750 in personal property and owned 72 slaves. In addition, as estate administrator for minor children related to his wife, Grist controlled another 48 slaves, for a total of 229. His son James R. Grist owned individually 84 slaves, giving the Grists ownership and management of 313 slaves. They leased additional slaves from other owners. [Source: NCPedia]

For readers unfamiliar with the pine tar industry of North Carolina, I will provide the following paragraph written by Ralph Goodrich (my g-g-grandmother’s brother) when he traveled from north to south through the pine forest region in 1859:

“These forests at first seemed to be without inhabitants either of man or of animals, but as we advanced from the dwarf and sparsely scattered pine & oak, which bordered on the outskirts, we came unexpectedly upon busy workmen. The thick undergrowth of brambles & briers was cut out. The pines were chipped into grooves about ten feet from the ground from which its pitch was oozing and dripping into the troughs beneath. Several log houses are scattered about, the furnace & warehouse, & barrels filled with the resin piled in stately rows or jumbled in utter confusion. In the distance we see clouds of smoke rising from huge black stacks of earth, while workmen are busy felling trees. We are in the midst of the tar and turpentine manufacturers, & in the midst of soot, smoke, and dirt. The ebony looks still more black, & the white man assumes a dusky countenance. We seemed to be hemmed in by a barrier of limitless forest, & shut out from every breeze so refreshing to the feverish cheek. At night we lay in a hammock tormented by mosquitoes, & lulled to sleep by the endless rattle of the locusts and the melancholy strain of the whippoorwill.” [Source: The Ralph Leland Goodrich Diaries, 1859-1867]

A Civil War linkage to the Grist family is the later use of the Grist mansion in Washington, NC. (https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/grist-james-redding), as a Union hospital. It still exists as a bed-and-breakfast residence and is notable for its secret rooms and passages (which may or may not have been of use during the Civil War).

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Richard Weiner and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Transcription

St. Pauls, North Carolina

July 28, 1851

Cousin Allen,

Cane got home yesterday the 26th with Stanley & Fitch. Riley [?] came within six miles of home & slipped off and left the mule in the road & is gone. We pursued him that night and tracked him 10 miles on the other side of Fayetteville next morning & he quit the road. Gar, he is gone back again. You ought to of chained him [to] Stanley & Fitch. I give them 40 [lashes] apiece and put them to work & they are working very well.

Cousin Allen, you seem to raise great complaints against me about the negroes. You know I treat negroes well and does not miss use them. I will give you a true statement of Mrs. Howard’s negroes—Br___, Sal & B___ & ___ has not had a lick this year. John has had a light whipping—say 15 or 20 [lashes]. Griffin & Stafford has been whipped but they [ ]. Henry has had three whippings. James R[edding] Grist was here & had two of them put on him—the first one and the last one. The other I put on.

You [lecture?] to me for the wearing [of chains?] and if it is not done, you will be [disappointed?] and complain of me. I have done my very best to have the work done & to keep the negroes satisfactory.

Cane was mistaken about the warehouse. It was done & he has him working on the wagons ever since. It is so dry & hot here—nothing can stand. The corn is dying. I am 10 crops of boxes behind in my shipping for the want of barrels. I keep [ ] still running. James wrote you all about the business.

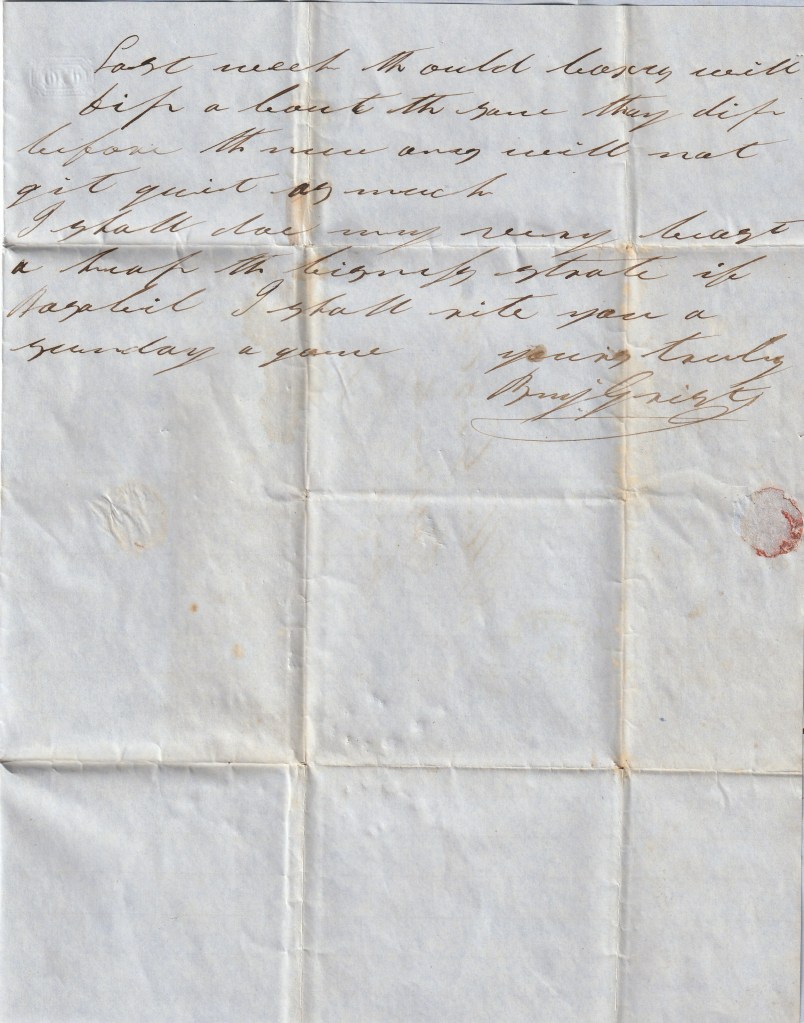

Last week the old boxes will ship about the same. They ship before the news ones and will not get quite as much. I shall do my very best to keep the business straight if possible. I shall write you a Sunday again.

Yours truly, — Benj. Grist