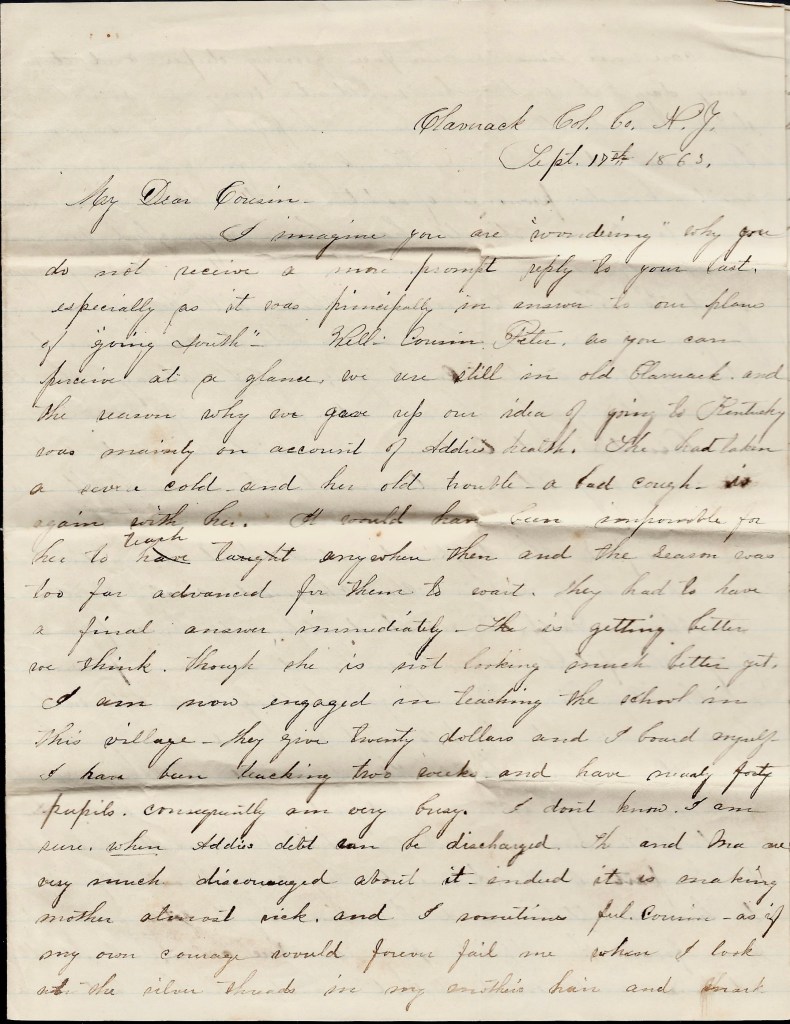

What a pleasure it is to read the words that spill from the glib tongue of an intelligent young woman. What follows is a letter composed in the midst of the American Civil War by 24 year-old Mary “Henrietta” Miller (1839-1912) of Claverack, Columbia county, New York, the daughter of William Albertson Miller (1813-1872) and Mary Hulst (1816-1883). Henrietta was an 1860 graduate of the Hudson Valley River School in Claverack (later renamed Claverack College).

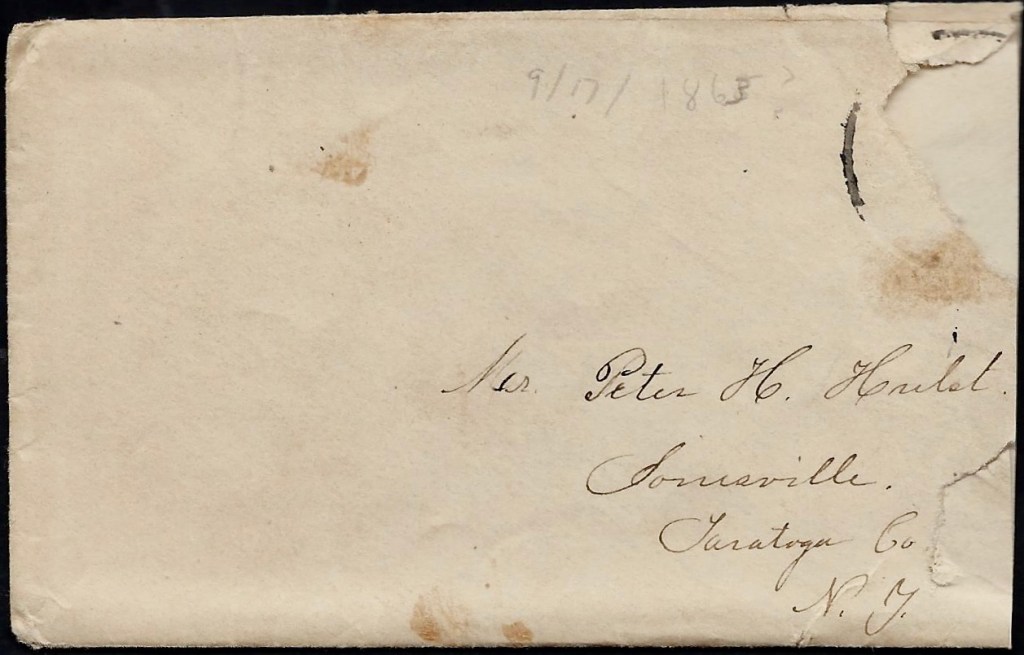

Henrietta wrote the letter to her cousin, Peter Henry Hulst (1841-1926). Peter “spent his earlier years in Fishkill-on-the-Hudson and at Carthage Landing. He later moved to Jonesville in Saratoga county where he taught school and began the study of medicine (Homeopathy), graduating from the Albany Medical College in 1866. He then practiced medicine in Schuylerville for a short time, moving to Greenwich in 1869.” [Obituary, Glens Falls, The Post Star, 28 October 1926]

In her letter, Henrietta suggests that she and her younger sister Adriana (“Addie”) Miller (1846-1905) had intended to relocate to Kentucky to teach school but decided against it when Addie fell ill. She did eventually move to Kentucky where she met James Solomon Crumbaugh in Scott county and after their marriage in December 1866, they settled in Old Crossing, Kentucky, where James ran a mill and Henrietta taught European Literature. In 1900 they moved to Kaufman county, Texas with their two children.

Henrietta’s letter dares to express her thoughts on politics, a subject rarely broached by women except in private conversation in mid 19th Century. She observes the political nature and consequences of the Conscription Act of 1863 and refers to President Lincoln as the “Republican Autocrat”—a sentiment shared by a great many Americans, particularly New Yorkers.

Transcription

Clarverack, Columbia county, New York

September 17th 1863

My dear cousin,

I imagine you are “wondering” why you do not receive a more prompt reply to your last—especially as it was principally in answer to our plan of “going South.” Well, Cousin Peter, as you can perceive at a glance, we are still in old Claverack and the reason why we gave up our idea of going to Kentucky was mainly on account of Addie’s health. She had taken a severe cold and her old trouble—a bad cough—is again with her. It would have been impossible for her to teach anywhere then and the season was too far advanced for them to wait. They had to have a final answer immediately. She is getting better we think though she is not looking much better yet.

I am now engaged in teaching the school in this village. They give twenty dollars and I board myself. I have been teaching two weeks and have nearly forty pupils; consequently am very busy. I don’t know, I am sure, when Addie’s debt can be discharged. She and Ma are very much discouraged about it. Indeed, it is making mother almost sick, and I sometimes feel, cousin, as if my own courage would forever fail me when I look at the silver threads in my mother’s hair and mark the careworn lines on her face growing deeper and deeper every day. I wish she wouldn’t worry so much about it and I do try to be as hopeful as I can on her account.

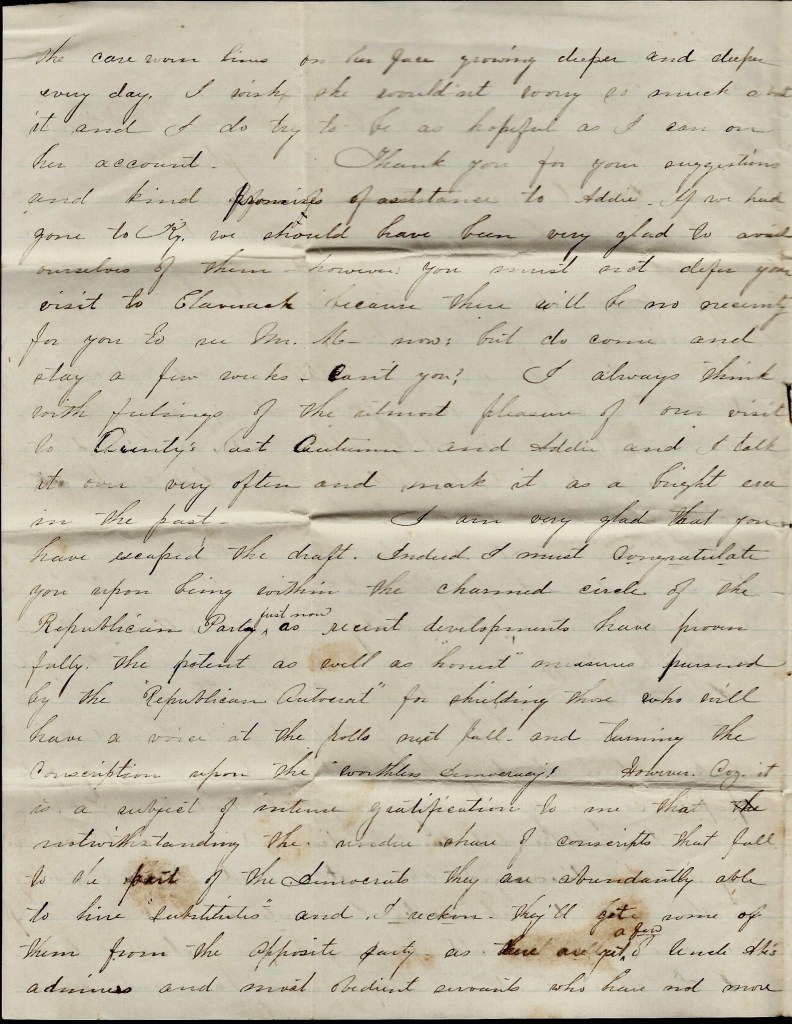

Thank you for your suggestions and kind promises of assistance to Addie. If we had gone to Kentucky, we should have been very glad to avail ourselves of them. However, you must not defer your visit to Claverack because there will be no necessity for you to see Mr. M[iller] now; but do come and stay a few weeks, can’t you? I always think with feelings of the utmost pleasure of our visit to Aunty’s last autumn and Addie and I talk it over very often and mark it as a bright era in the past.

I am very glad that you have escaped the draft. Indeed, I must congratulate you upon being within the charmed circle of the Republican Party just now as recent developments have proven fully, the potent as well as “honest” measures pursued by the “Republican Autocrat” for shielding those who will have a voice at the polls next fall and turning the conscription upon the worthless democracy. However, coz., it is a subject of intense gratification to me that notwithstanding the undue share of conscripts that fall to the part of the Democrats, they are abundantly able to hire “substitutes” and I reckon they’ll get some of them from the opposite party as there are yet a few of Uncle Abe’s admirers and most obedient servants who have not more of the “green” currency than they know what to do with. But perhaps you are like some of the gentlemen that I know; “you do not like to hear a lady talk politics.” If no, pardon me and I will change the subject. Nonetheless, “them’s my sentiments.”

Ma has been up to see Grandma this fall. Went a few weeks ago. She made a very short visit as she was expecting us to go to Kentucky. The weather here has been very warm and pleasant. Now it is cloudy and cold. I have to walk about a mile to my schoolroom and I should like it to be pleasant weather all the time if it could be so, but I anticipate many a cold, wet walk this winter. School has just opened at the Seminary and I dare say Mr. [Alonzo] Flack 1 has begin again upon his well beaten track of—I guess I won’t say it after all, for I could not say any good of him so it is better to leave the sentence unfinished.

I am glad your health is improved. Are you taking vocal or instrumental music, or both? Pa and Ella have the whooping cough. They have been very bad but seem to be getting over it now somewhat. Dear cousin, I must beg your kind indulgence for this disconnected and ill written missive. I am not very well nor very much in the mood for writing tonight so I will close. Please write me soon and accept the love & best wishes of your affectionate cousin, — Henrietta

1 Alonzo Flack was born in Argyle, New York on September 19, 1823. While attending Union College (1845-1849), Flack joined the Methodist Episcopal Church and received a license as a preacher. He subsequently studied theology at the Concord Biblical Institute in New Hampshire and was recrutied by Bishop Osman C. Baker in 1854 to serve as principal for a new school at Charlotte. In 1855, Flack became principal of the Claverack College and Hudson River Institute. He later assumed the presidency of Claverack College in 1869. Flack was noted for his deep belief in the reform movements of the period, including temperance reform, the enfranchisment of women and ecclesiastical reform. He was granted a Doctor in Philosophy degree by the University of the State of New York in 1875. Much esteemed by his students, Flack served for thirty years as a teacher and administrator at the school, until his death in 1885. He was succeeded by his son, Rev. Arthur H. Flack, who occupied the position until 1900. The College, located in Claverack, New York, offered academic and classical studies to ladies and gentlemen and was very highly regarded. Alumni included author Stephen Crane, feminist Margaret Sanger, and President Martin van Buren. [sources consulted: Minutes of the annual conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church: Spring conferences of 1885. (p. 97)]

In 2011 I transcribed a letter by Alonzo Flack and posted it on Spared & Shared 1. See—1842: Alonzo Flack to Nathan Henry Bitely.