The following letter was written by Eber L. Robinson (1828-1903), the son of Eber Robinson (1792-1863) and Alzade Lee (1807–Bef1860) of East Windsor, Hartford county, Connecticut.

Eber was 31 years old when he enlisted as a private in Co. B, 11th Connecticut Infantry. He was discharged for disability on 22 October 1862 after one year’s service.

Eber’s letter gives a description of the battle and battlefield on Roanoke Island though his regiment was not engaged in the actual fighting. The battle took place on February 7-8, 1862.

Transcription

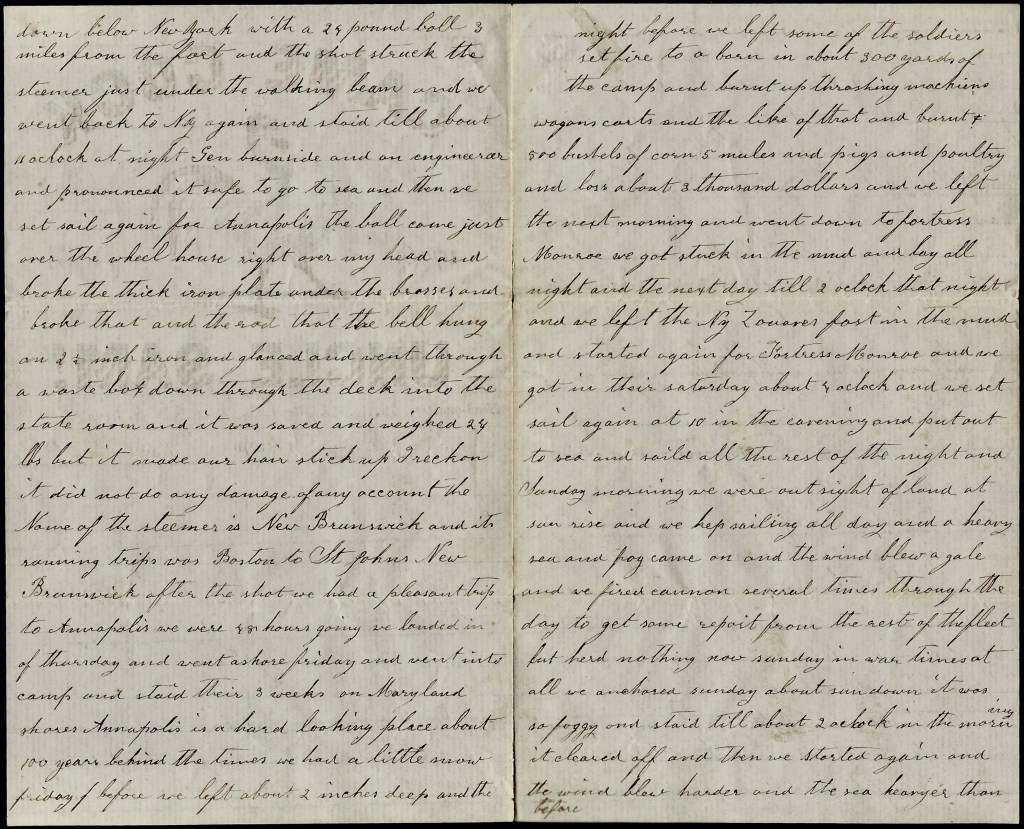

Headquarters Roanoke Island

11th Regiment, Co.B, Connecticut Vols.

Gen. Burnsides Division

March 6, 1862

Dear Sir,

As I have a little leisure time, I thought I would improve it by writing you a few lines as it is a long time since I have been home or seen anyone or heard from anyone. I have been sick for 18 days but have got better now so as to drill again.

We had rather a hard time of getting here. We got shot into by Fort Hamilton down below New York with a 24-pound ball 3 miles from the fort and the shot struck the steamer just under the walking beam and we went back to New York and staid till about 11 o’clock at night. Gen. Burnside and an engineer ran and pronounced it safe to go to sea and then we set sail again for Annapolis. The ball came just over the wheel house right over my head and broke the thick iron plate under the brasses and broke that and the rod that the bell hung on—an 2½ inch iron—and glanced and went through a waste box down through the deck into the state room and it was saved and weighed 24 Ibs. But it made our hair stick up, I reckon. It did not do any damage of any account. The name of the steamer is New Brunswick and its running trips was Boston to St. Johns, New Brunswick. 1

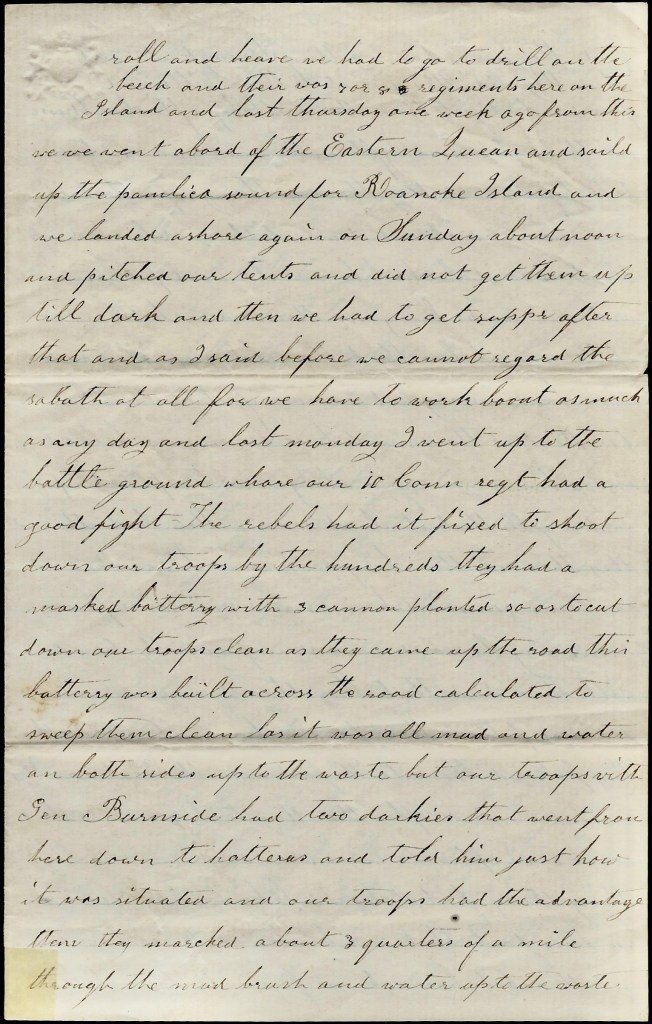

After the shot, we had a pleasant trip to Annapolis. We were 48 hours going. We landed on Thursday and went ashore Friday and went into camp and staid there 3 weeks on Maryland shores. Annapolis is a hard-looking place—abut 100 years behind the times. We had a little snow Friday before we left about 2 inches deep. The night before we left, some of the soldiers set fire to a house about 300 yards of the camp and burnt up thrashing machines, wagons, carts and the like of that, and burnt 500 bushels of corn, 5 mules and pigs and poultry and [the] loss [was] about 3 thousand dollars.

We left the next morning and went down to Fortress Monroe. We got stuck in the mud and lay all night and the next day till 2 o’clock that night and we left the New York Zouaves fast in the mud and started again for Fortress Monroe and we got in there Saturday about 4 o’clock.

We set sail again at 10 in the evening and put out to sea and sailed all the rest of the night and Sunday morning we were out [of] sight of land at sunrise and we kept sailing all day and a heavy sea and fog came on and the wind blew a gale and we fired cannon several times through the day to get some report from the rest of the fleet but herd nothing. No Sunday in war times at all.

We anchored Sunday about sundown—it was so foggy—and staid till about 2 o’clock in the morning [when] it cleared off and then we started again [although] the wind blew harder and the sea heavier than before and we made Hatteras light house about sunrise. We had a very hard time. We came near getting swamped two or 3 pitches and we came near going under, but we righted up again and sailed down the cape and rounded the point and sailed into the Inlet and anchored just in time for it came on harder than ever. The same afternoon, one steamer was drove onto the breakers and went to pieces before morning with 15 cannon on board, and some vessels sunk in the inlet. Several steamers and schooners sunk in sight of us.

We were on board this Steamer Sentinel [for] 22 days without going ashore. We went ashore and went up 5 miles and camped on the Island and staid there 4 weeks. Hatteras Island is quite a pleasant [place]. The live oaks upon holly berries, ironwood trees and shrubs are all green with blue, red, and black berries and white ones too. We had our camp in a grove of this kind and they planted sweet potatoes middle of February. Figs grow here a plenty. The robins, blackbirds, bluebirds, and the thrush and English robins sing so sweetly and the frogs peep and croak beautifully, and it is most delightful to see the bright dashing billows roll and heave. We had to go to drill on the beach and there were 7 or 8 regiments here on the Island.

Last Thursday, one week ago from this, we went aboard of the Eastern Queen and sailed up the Pamlico Sound for Roanoke Island and we landed ashore again on Sunday about noon and pitched our tents and did not get them up till dark. Then we had to get supper after that, and as I said before, we cannot regard the Sabbath at all for we have to work about as much as any day.

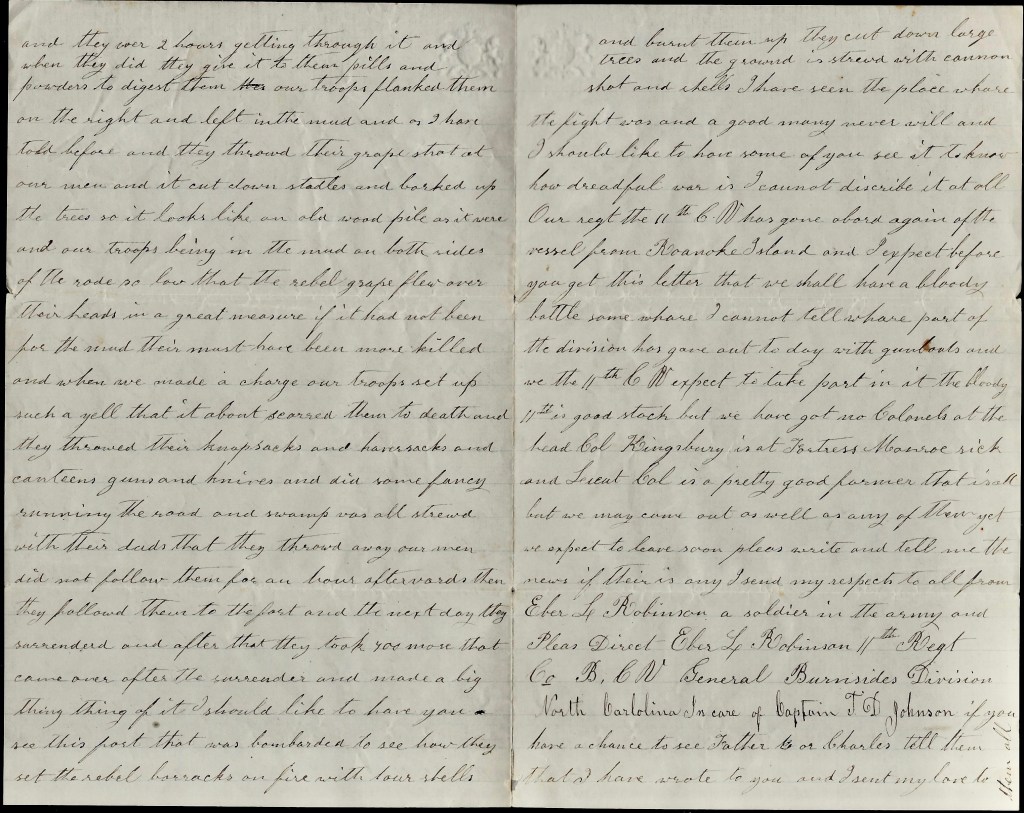

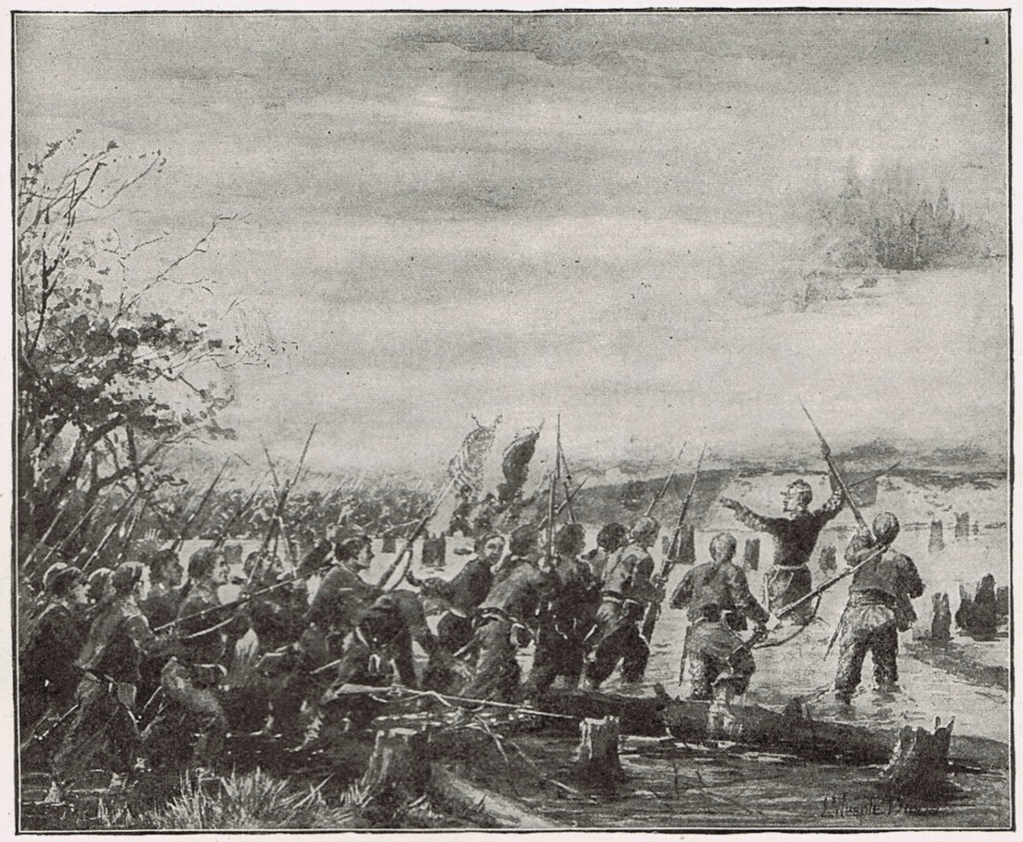

Last Monday I went up to the battle ground where our 10th Connecticut Regiment had a good fight. The rebels had it fixed to shoot down our troops by the hundreds. They had a masked battery with 3 cannon planted [on Supple’s Hill] so as to cut down our troops clean as they came up the road. This battery was built across the road calculated to sweep them clean for it was all mud and water on both sides up to the waist, but our troops with Gen. Burnside had two darkies that went from here down to Hatteras and told him just how it was situated and our troops had the advantage then. They marched about 3 quarters of a mile through the mud, brush, and water up to the waist and they were 2 hours getting through it, and when they did, they give it to them pills and powder to digest them. Our troops flanked them on the right and left in the mud. As I have told before, they throwed their grape shot at our men and it cut down stodles [?] and barked up the trees so it looks like an old wood pile as it were. Our troops, being in the mud on both sides of the road so low that the rebel grape flew over their heads in a great measure. If it had not been for the mud, there must have been more killed.

When we made a charge, our troops set up such a yell that it about scared them to death and they throwed their knapsacks and haversacks and canteens, guns, and knives, and did some fancy running. The road and swamp was all strewed with their duds that they throwed away. Our men did not follow them for an hour afterwards. Then they followed them to the fort [Fort Barstow] and the next day they surrendered and after that they took 700 more that came over after the surrender and made a big thing of it. I should like to have you see this fort that was bombarded to to see how they set the rebel barracks on fire with our shells and burned them up. They cut down large trees and the ground is strewed with cannon shot and shells. I have seen the place where the fight was and a good many never will. I should like to have some of you to see it to know how dreadful war is. I cannot describe it at all.

Our regiment—the 11th Connecticut Volunteers—has gone aboard again of the vessel from Roanoke Island and I expect before you get this letter that we shall have a bloody battle somewhere. I cannot tell where. Part of the division has gone out today with gunboats and we, the 11th C. V., expect to take part in it. The Bloody 11th is good stock but have got no colonel at the head. Col. Kingsbury is at Fortress Monroe sick and Lieut. Col. is a pretty good farmer [but] that is all. But we may come out as well as any of them yet. We expect to leave soon. Pleas write and tell me the news, if there is any. I send my respects to all. From Eber L. Robinson—a soldier in the army and please direct to Eber L. Robinson, 11th Regt., Co. B, C. V., General Burnside’s Division, North Carolina, in care of Captain T. D. Johnson.

If you have a chance to see Father or Charles, tell them that I have wrote to you and I send my love to them all.

1 This incident was reported in the New York Times as follows: “STEAMER NEW BRUNSWICK, AT ANCHOR OFF ANNAPOLIS, Friday, Dec. 20, 1861. The Connecticut Eleventh, which arrived in New-York on Tuesday, en route for Annapolis, reembarked on the afternoon of that day on the transports New-York and New-Brunswick–the right wing of the regiment upon the former, the left upon the latter. The fortunes of the left wing are those of your correspondent, and they iuclude a one-sided naval engagement which took place at about 6 o’clock in the evening, near Fort Hamilton, and which ended in the ignominious defeat of our transport, which was obliged to return to her anchorage off the “Battery,” the Captain and engineers supposing her to be disabled.

The facts in the case are simply these: The transport left the pier at about dusk and steamed down the bay. When near Fort Hamilton she was challenged by a Government vessel, in the usual manner — i.e., a shot across her bow. For reasons as yet unknown the transport held her course, regardless of the challenge. Another shot from the vigilant sentinel, and a ball whistles over our devoted heads; still the transport holds her course; a signal rocket from the sentinel vessel and Fort Hamilton opens upon us with a 24-pounder, the shot crashing through the machinery and passing out of a state-room. This had the desired effect, and the transport hove to. It is hardly less than a miracle that not one of the five hundred on board was injured. Had the ball entered the boat in any other direction, or a few feet higher or lower, many lives must have been sacrificed to the criminal carelessness of whoever is responsible for the safe conduct of the troops. How does it happen that there are men employed by Government on transports so stupidly ignorant of their profession? With the exception of those in charge, who were directly responsible, I believe it would be difficult to find a man among us who did not understand the meaning of the first shot. This accident (if such it can properly be called) occasioned a delay of some six hours, and these hours cost the Government at the rate of about seven hundred dollars per day.”