The following letters were written by Lewis Burwell Hutchinson (1832-1910), the son of Rev. Eleazer Carter Hutchinson (1804-1876) and Lucy Burwell Randolph (1809-1877). According to his biography on Find-A-Grave, Lewis’s father was one of the pioneers of Episcopalianism in Missouri. He was the rector of the Trinity Protestant Episcopal Church in St. Louis. He was married to Lucy Burwell Randolph, daughter of Archibald Cary Randolph and Lucy Burwell, who was the daughter of Nathaniel Burwell of Clarke County, Virginia.

I could not find a biographical sketch for Lewis but I was able to cobble together the following from census and family records, school and military records, all available on the internet. The first notice of him was in 1843 when only eleven years; he was enumerated as a student in the preparatory department of Kemper College near St. Louis. The next notice of him was his attendance from 1846 to 1848 at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. While at student at Norwich, in March 1849, he was nominated by the Missouri House of Representative J. B. Bowlin for an appointment to West Point but he was not admitted and continued with his studies at Norwich. In 1852 he was listed among the Sophomores at the College of New Jersey (Princeton). I can’t find any evidence that he graduated from Princeton.

It appears that Lewis was swept up in the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush of 1859 and traveled overland with a company from Des Moines, Iowa, who panned for gold together in the Pike’s Peak region and later along the waters of the Big Blue in the South Park region (see Letter 1). He apparently returned in the late summer of 1860 for he was married on 4 October 1860 to Elizabeth (“Libbie” or “Lib”) E. Gearhart (b. 1841), the daughter of George Gearhart (1806-1894) of Dodgeville, Des Moines county, Iowa. Lewis and Libbie’s only child, Augustus (“Gussie”) Carter Hutchinson was born on 14 August 1861 in Iowa, but by this time, however, the Civil War had begun and Lewis had left home to volunteer as a 1st Sergeant in Co. F, 1st Missouri (Confederate) Infantry. His muster rolls state that he was a Civil Engineer in St. Louis prior to his joining the Missouri Infantry. He was breveted a 2nd Lieutenant’s commission (by election) in May 1862. His record shows him to have participated in the battles of Shiloh, Corinth, Tuscumbia river, Grand Gulf, Port Gibson, Baker’s Creek, and Big Black.

Lewis endured the siege and was among the troops surrendered by General Pemberton at Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. The overwhelming number of prisoners of war surrendered at Vicksburg compelled Grant to implement a different treatment approach compared to those captured elsewhere. Rather than transferring them to Northern POW camps, Grant paroled the POWs at Vicksburg, allowing them to return home unarmed for a period of 30 days. After this timeframe, they were obligated to report to camps in their respective states and pledge not to reengage in combat against the United States until their exchange. Many Confederates, disillusioned by the war and plagued by declining morale, seized this opportunity to evade further military obligations. In Hutchinson’s case, his Muster Roll indicates that he was marked absent without leave since September 27, 1863. He departed from his command at Demopolis, Alabama, and was “last heard from in St. Louis.” Another document in his file asserts that he deserted on August 20, 1863. An undated record states that he was “reduced to the ranks for bad conduct,” potentially occurring after his desertion. The final official entry on his muster roll notes that he was “dropped by order of Secretary of War, January 27, 1864.”

Before concluding the biographical sketch of Lewis, I should here mention that he had two brothers who also served with him in the 1st Missouri (confederate) Infantry. Lewis’ younger brother, Robert Randolph (“Ran” or “Ranny”) Hutchinson, joined the 1st Missouri Infantry as Colonel John Bowen’s AAG. After Bowen’s death, Hutchinson transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia where he took a similar position under General Robert Rodes. He fought in all the army’s battles until his capture at the Battle of Cedar Creek. After his release as a prisoner, he returned to St. Louis. Prohibited from serving as a lawyer in Missouri by the postwar administration, he started a new career as a banker, working his way from cashier to president of the Mechanics Bank of St. Louis. The other brother, Virginius “Cary” Hutchinson (1843-1863) enlisted as private in Co. F of the 1st Missouri Infantry in 1862 but the muster rolls for January through June 1863 show that Cary was on detached service. He was employed on extra duty at Bowen’s Division Headquarters, on order of General Bowen, as a clerk for the A.A.G. The A.A.G. of Bowen’s Division was Cary’s brother, Robert Hutchinson. Cary died from “congestion of the brain.” He was initially interred at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Vicksburg. He was removed, returned to St. Louis, and interred at Bellefontaine on August 28, 1863.

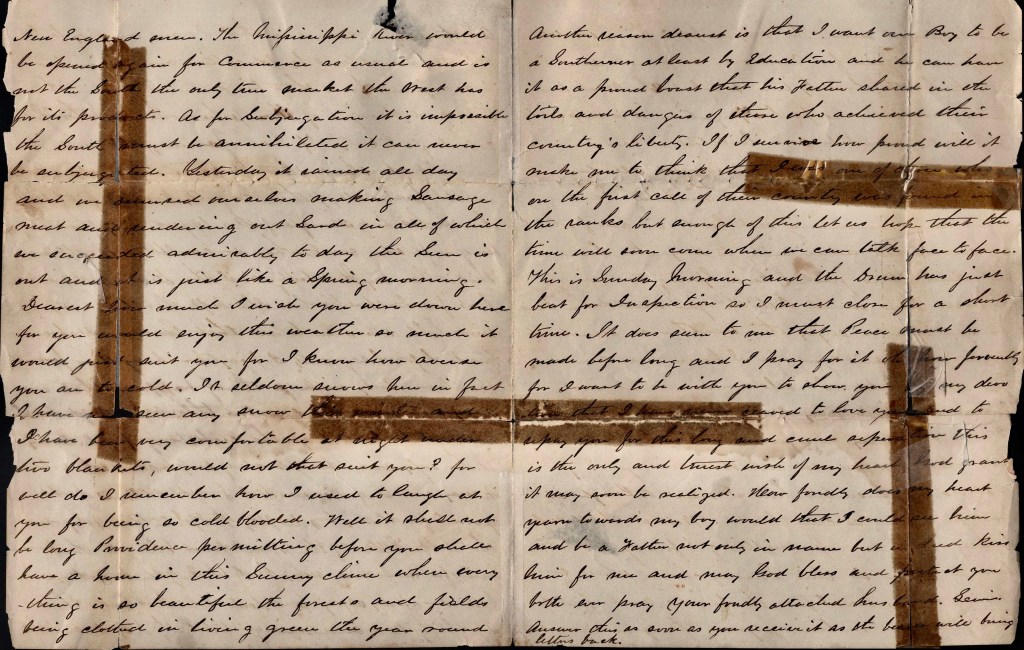

To resume with Lewis’s biographical sketch, following his desertion from the Rebel army in Demopolis, Alabama, there exists a theory suggesting he attempted to reunite with his parents and/or wife in Missouri or Iowa, only to be captured and subsequently transported to Fort McHenry or Point of Rocks in Maryland. It is there that he purportedly took the Oath of Allegiance and enlisted in the Navy, although I have been unable to locate any concrete records to substantiate this claim. Another theory posits that he secretly engaged in what is now referred to as the “Chesapeake Affair” in December 1863, an incident that significantly strained US-British relations. Lewis’s letter dated 24 December 1863 (Letter 5) appears to lend some credence to this assertion; however, he provides scant detail, merely stating, “We are not allowed to tell of our whereabouts so that must be left to your own imagination and what you can gather from the newspapers. I suppose you heard of the affair of the ‘Chesapeake.’ If so, you need not be alarmed for I am safe and well.” What is definitively known is that, under “Maryland soldiers in the Civil War,” Lewis Hutchinson is recorded as having enlisted as an Ordinary Seaman on 23 June 1864, mustering out on 21 June 1865, and serving aboard the USS Princeton and the USS Juniata.

In the letters that Lewis composed to his wife from aboard the USS Juniata in the war’s final year, he implored her repeatedly for forgiveness regarding his wayward behavior. “I recognize that I have not treated you as I ought to have, and during the solitary hours of my nighttime watch, thoughts of you flood my mind, and I have profoundly regretted the decisions I made in life and my treatment of you,” he expressed. He attributed some of his lamentable actions to intemperance. A reconciliation appeared conceivable—Lewis yearned for it—but reading between the lines reveals that the bonds of affection may have been strained beyond mending during their prolonged separation, leading Libbie to rely on her relatives in Dodgeville for support. It surely vexed Lewis to learn that his 3-year-old son wished to travel to Dixie to kill Rebels.

Reconciliation failed. In the 1870 US Census, 29-year-old Libbie was recorded in her father’s household in Osceola, Clarke County, Iowa, alongside her 8-year-old son, Carter. A decade later, she was documented in her own residence in Osceola, with her 18-year-old son, identified as “widowed,” despite the fact that Lewis was alive and residing in Yalobusha County, Mississippi. The official status of Lewis and Libbie’s marriage remains ambiguous, as I have been unable to locate any record of divorce. It appears that when reconciliation was deemed impossible, Lewis chose to abandon Libbie, moving to Yalobusha County, Mississippi, where he subsequently married Adeline Kincaid Hughes (b. 1837). Together, they had at least two children: William Wright Talcott Hutchinson (b. 1868) and Charles Lewis Randolph Hutchinson (1873-1937). On March 7, 1883, Lewis was appointed as the U.S. Postmaster at Hatton, Yalobusha County, Mississippi. The 1900 US Census lists Lewis (age 67) residing in Beat 4, Yalobusha County, Mississippi, where he was employed as a bookkeeper. In the 1910 US Census, shortly before his death, Lewis was recorded living in Yalobusha, Mississippi, in the household of his son Charles.

Letter 1

“Golden Run Diggings”

June 19th 1860

I will again intrude upon you dearest with one of my uninteresting scrawls. I am now on the western slope of the mountains having left “Tarryall” some two weeks since. Golden Run is a small stream emptying into Blue River which is one of the tributaries of the great Colorado of the West. We have purchased the claim upon which we now are at work and are at work “prospecting” it; as yet our show is dull enough but with strong hands and willing hearts we hope at least to accomplish something. This is about all that I can tell you in reference to my whereabouts and doings but it was not for this purpose that i intended to write to you so soon after my last—especially as one letter is all you have designed to honor me with.

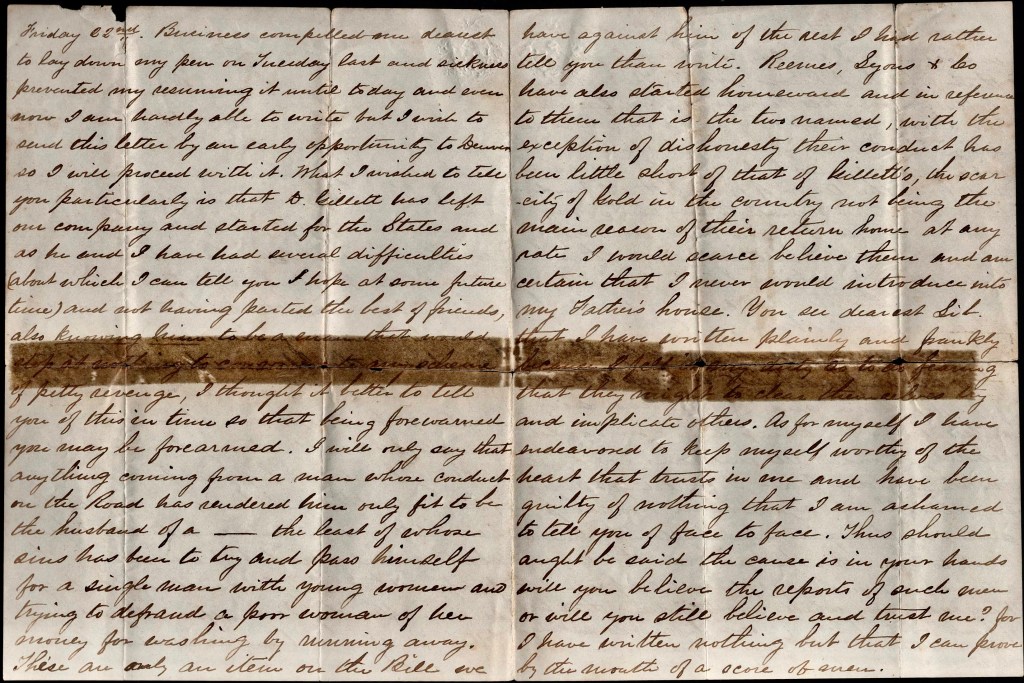

Friday, 22nd. Business compelled me dearest to lay down my pen on Tuesday last and sickness prevented my resuming it until today and even now I am hardly able to write. But I wish to send this letter by an early opportunity to Denver so I will proceed with it. What I wished to tell you particularly is that D. Gillett has left our company and started for the States and as he and I have had several difficulties (about which I can tell you I hope at some future time) and not having parted the best of friends, also knowing him to be a man that would stop at nothing to [illegible] any scheme of petty revenge, I thought it better to tell you of this in time so that being forewarned you may be forearmed. I will only say that anything coming from a man whose conduct on the road has rendered him only fit to be the husband of a ____ the least of whose sins has been to try and pass himself for a single man with young women and trying to defraud a poor woman of her money for washing by running away. These are only an item on the Bill we have against him. Of the rest, I had rather tell you than write. Reemes, Lyons & Co. have also started homeward and in reference to them—that is, the two named, with the exception of dishonesty, their conduct has been little short of that of Gillett’s, the scarcity of gold in the country not being the main reason of their return home. At any rate, I would scarce believe them and am certain that I never would introduce [them] into my Father’s house.

You see, dearest Lib, that I have written plainly and frankly because I felt it my duty so to do fearing that they might to clear themselves try and implicate others. As for myself, I have endeavored to keep myself worthy of the heart that trusts in one andn have been guilty of nothing that I am ashamed to tell you of face to face. Thus should ought be said the cause is in your hands. Will you believe the reports of such men or will you still believe and trust me? for I have written nothing but that I can prove by the mouth of a score of men. Do not say that I am not altogether innocent or I would not seek to justify that which I know not of. The experience of the past in Des Moines County has learned me always to keep my sword by my side ready at all times for instant combat not with open enemies but midnight assassins. And from the tenor of your letter I find that I cannot even now lay aside my armor nor do I claim total immunity from all sin. I will now drop this subject only asking you to judge of me as you know me—not as every would be meddler would have me to be.

Everything here is so dirty that it is an impossibility to keep a sheet of paper clean and if you had any experience in camp life, you would readily excuse all uncleanness and rather wonder how I could get along so well. I am again alone in camp and my thoughts are constantly wandering back to you. Bye the bye, I must thank you a thousand ties for a pleasant surprise I had yesterday which was finding that lock of hair in the back of your likeness making only a stronger link to bind my heart to you that distance can neither bend or break.

Since Tuesday evening I have been quite unwell with a fever but am now so far convalescent as to be about although quite weak. The fancies and dreams of a sick person are sometimes so strange that I cannot refrain from telling you two of mine during my illness. The first was that I had returned and that you treated me so coldly that I could bear it no longer so rising, I threw at your feet a bag of gold saying “it was for you alone that I endured the hardships of a life in the mountains—for you that I toiled in the muddy ditch day after day of weary existence—and this is now by recompense? Take the result of my labors—it is yours, for thoughts of you alone made labor bearable. Take it and enjoy it above the ruins of a broken heart, nor ever let one thought of what I will be ever disturb you.” Will this ever be a fearful truth? I pass it over, dearest, as only the vain dream of a sick man.

The other was more singular and is as vividly impressed upon my mind as with letters of fire. I thought that I lay among many other men, none of whose faces I could recognize. White exhalations twisted and curled up stealthily from the ground, approached the men, touched them, and stretched them out dead, one by one in the places where they lay. Then I thought I heard your voice in agony calling me to escape. “Remember your promise to me. Come back before the pestilence reaches you and lays you dead like the rest!” My reply was “Wait! I shall come back. The night that recorded our oath in Heaven was the night that set my life apart for an [illegible] or there welcomed back in the land of my birth. I am still walking on that road that leads me to your love. The pestilence which touches the rest will pass me.” Again I was in the forest and the figures of dark men lurked behind the trees with bows in their hands and arrows fitted to the strings. Once more you cried out, “Another stop on the road.” I answered, “The arrows that strike the rest will spare me.” For the last time I saw myself kneeling by a tomb of white marble and the shadow of a veiled woman rose out of the grave and waited by my side. I could hear myself say, “Darker and darker, farther and farther yet. Death takes the good, the beautiful, and spares me. The pestilence that wastes, the arrow that strikes, the grave that closes over love and hope are steps of my journey and take me nearer and nearer to the end.”

I then awoke in agony of mind only to find myself almost in a delirium of fever. I have not written these to frighten you but only as singular specimens of the vagaries of mind acted upon by disease of the body. Now Lib, I will give you the news.

Our prospects are much brighter than when I commenced that letter—so much so that I may be back sooner than I had dared to anticipate. In my next, I will give you a full account of our gains and losses. We are now in Utah Territory!!! What a glorious chance to turn Mormon and as we have not caught a glimpse of a young lady’s dress since leaving the Missouri River, don’t you think in Brigham Young and a committee of ladies from Salt Lake should make their appearance among us that we would be made proselytes of whether or no?

Now hold your breath for a minute for I have something to tell you that may not only make you but a score of young ladies in Des Moines scream with joy. Well, here it is. Charlie Kline is well and working only a mile and a half from here. My dearest friend (you know how) Frank Clark is on the same gulch with us only a half mile from our claim. We are of course very intimate. Nearly all the refugees from Des Moines are on this gulch and it makes it decidedly pleasant, I can assure you. I have just learned that there is a letter for me in Tarryall which I expect tomorrow and I am praying that it may be from you. Until I receive it, I will leave this open. Do write soon to me, Lib, and remember that there there is a heart [illegible] than that of your devoted Lewis, Goodbye.

Letter 2

“Camp Calhoun”

Near Memphis, Tennessee

July 22nd 1861

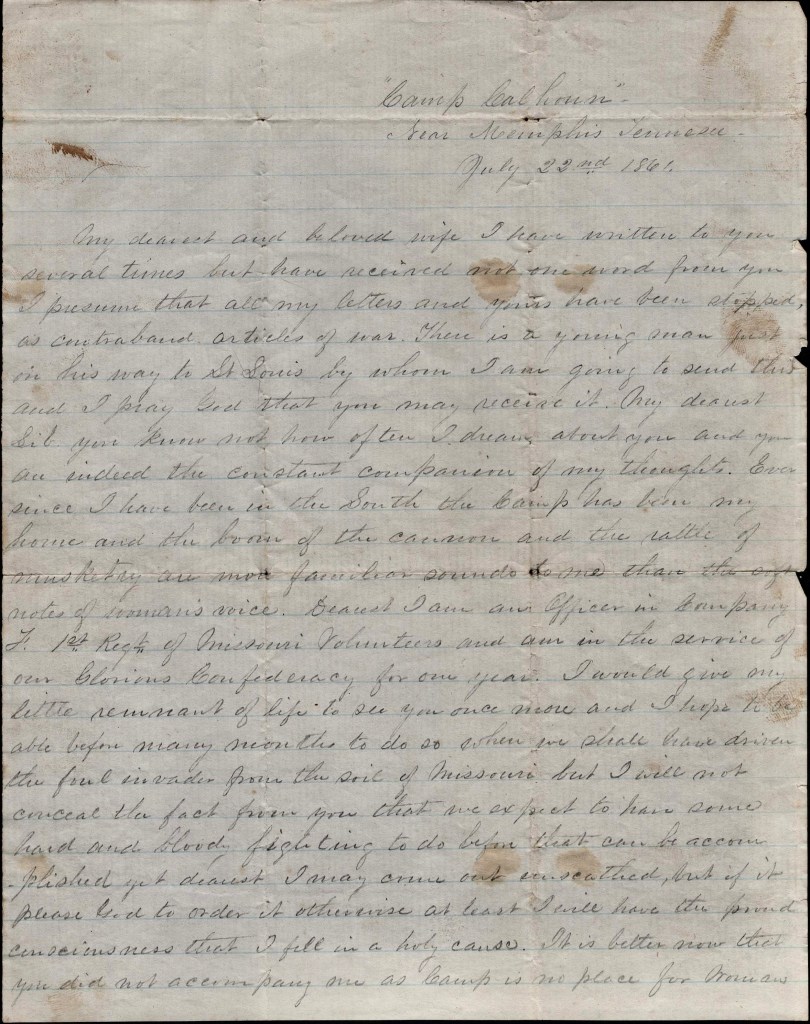

My dearest and beloved wife,

I have written to you several times but have received not one word from you I presume that all my letters and yours have been stopped as contraband articles of war. There is a young man just on his way to St. Louis by whom I am going to send this and I pray God that you may receive it. My dearest Lib, you know not how often I dream about you and you are indeed the constant companion of my thoughts. Ever since I have been in the South, the camp has been my home and the boom of the cannon and the rattle of musketry are more familiar sounds to me than the soft notes of woman’s voice.

Dearest, I am an officer in Company F, 1st Regiment of Missouri Volunteers and am in the service of our glorious Confederacy for one year. I would give my little remnant of life to see you once more and I hope to be able before many months to do so when we shall have driven the foul invader from the soil of Missouri but I will not conceal the fact from you that we expect to have some hard and bloody fighting to do before that can be accomplished. Yet dearest, I may come out unscathed, but if it please God to order it otherwise, at least I will have the proud consciousness that I fell in a holy cause. It is better now that you did not accompany me as camp is no place for woman and as we are constantly on the move, but just so soon as we get into Missouri, I will do all in my power to have you brought to me—that is, if you will come. We expect to march into Missouri shortly and will endeavor to force our way, driving the enemy before us.

Lib, I will not conceal from you that in less than three weeks I may be in the midst of battle, yet I do not fear to fall. I feel as if you were a protecting angel to me and that we will once more be restored to each other’s arms—at least let us pray God that such will be the case. Do not, my dearest, indulge in any gloomy apprehensions, but think that all will yet be well; that Heaven is on this side I have embraced and if I fall, it will be as a glorious martyr. When I think of the wrongs that had been inflicted upon us—nay, ever heaped up, and of the unprovoked massacres that have occurred in St. Louis, I fairly pine to be on the battlefield. But enough of this.

Dearest, you must write directing to Father who will send your letter by some private conveyance as soon as you get this for I do so long to hear from you. I am so lonely. You must write me a long letter all about yourself and about one thing I am particularly anxious to know, then my wife tell me whether your fears in reference to becoming a Mother are to be realized or not? Dearest. I have saved up over a hundred dollars that I want to send to you but I know not how to do it. As soon as I find an opportunity, I will send it, but everything is so uncertain. Lib, I want you to send me that likeness I carried to Pike’s Peak with me. Wishing that God will bless, comfort, and protect you, my dearest wife, I must bid you goodbye dearest and best beloved. If we meet not on earth, let us meet in Heaven. Your husband.

Letter 3

“Camp Rogers”

December 28th 1862

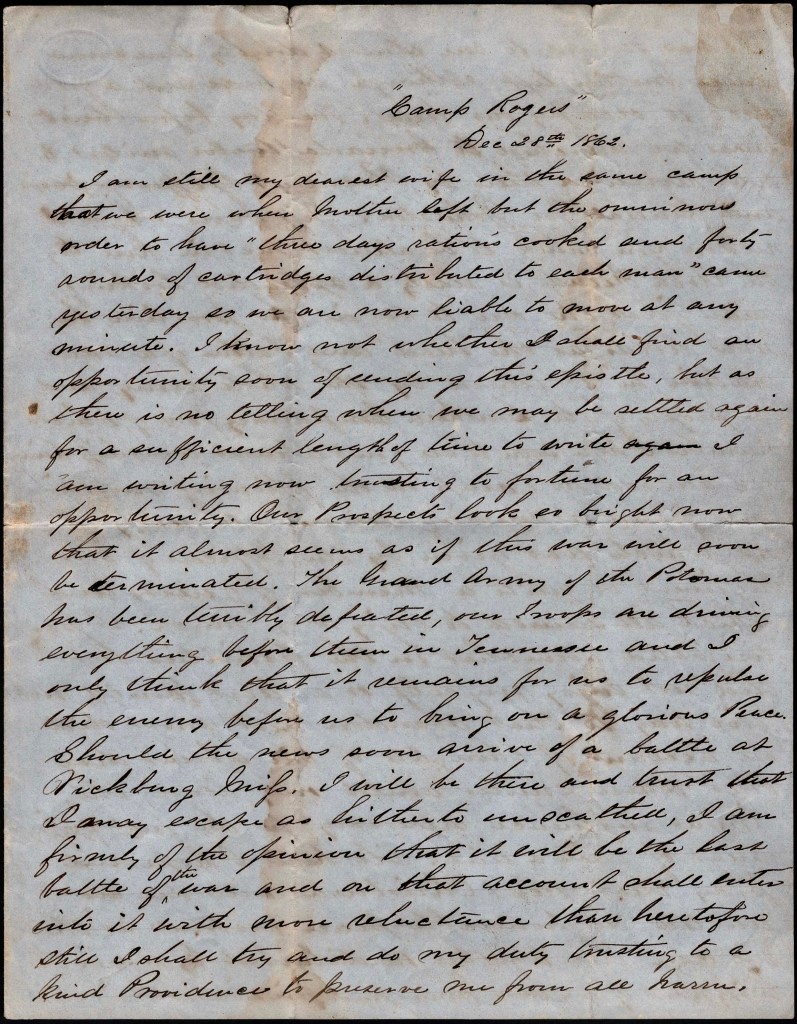

I am still, my dearest wife, in the same camp that we were when Mother left but the ominous order to have “three days rations cooked and forty rounds of cartridges distributed to each man” came yesterday so we are now liable to move at any minute. I know not whether I shall find an opportunity soon of sending this epistle, but as there is no telling when we may be settled again for a sufficient length of time to write, I am writing now trusting to fortune for an opportunity. Our prospects look so bright now that it almost seems as if this war will soon be terminated.

The Grand Army of the Potomac has been terribly defeated [at Fredericksburg], our troops are driving everything before them in Tennessee and I only think that it remains for us to repulse the enemy before us to bring on a glorious peace. Should the news soon arrive of a battle at Vicksburg, Mississippi, I will be there and trust that I may escape as hitherto unscathed. I am firmly of the opinion that it will be the last battle of the war and on that account shall enter into it with more reluctance than heretofore. Still I shall try and do my duty trusting to a kind Providence to preserve me from all harm.

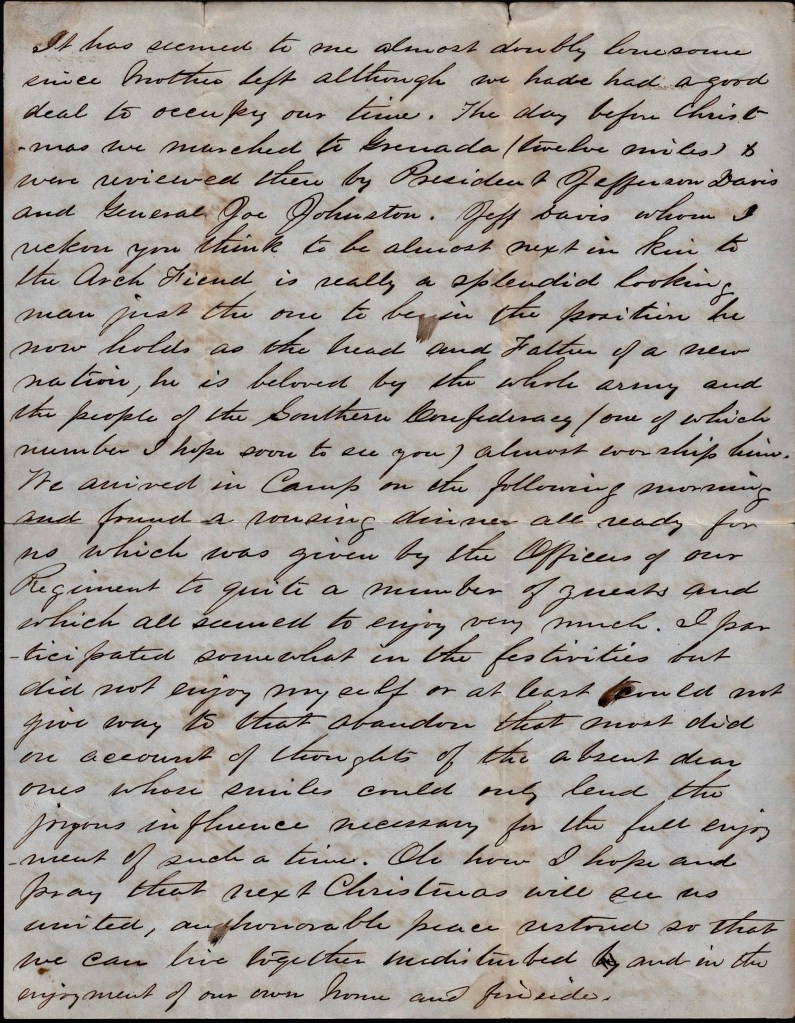

It has seemed to me almost doubly lonesome since Mother left although we have had a good deal to occupy our time. The day before Christmas we marched to Grenada (twelve miles) & were reviewed there by President Jefferson Davis and General Joe Johnston. Jeff Davis, whom I reckon you think to be almost next in kin to the Arch Fiend, is really a splendid looking man—just the one to be in the position he now holds as the head and Father of a new nation. He is beloved by the whole army and the people of the Southern Confederacy (one of which number I hope soon to see you) almost worship him.

We arrived in camp on the following morning and found a rousing dinner all ready for us which was given by the officers of our regiment to quite a number of guests and which all seemed to enjoy very much. I participated somewhat is the festivities but did not enjoy myself or at least could not give way to that abandon that most did not account of thoughts of the absent dear ones whose smiles could not lend the joyous influence necessary for the full enjoyment of such a time. Oh how I hope and pray that next Christmas will see us united and honorable peace restored so that we can live together undisturbed and in the enjoyment of our new home and fireside.

I am going to try and get this letter off tomorrow so I must close it right soon. You must try, my dear Lib, to keep up a good heart until I see you next spring for if I survive the next great battle, we will certainly meet before long. How will you like the idea of coming to Dixie to live? How is our boy? Does he grow fast? Who does he resemble and can he talk yet? How I long to see him. Send me a lock of his hair, can’t you? As soon as I can, I will write to you again assuring you of my safety. Farewell and God bless you my dearest wife and child (kiss him for me) and may we soon meet is the fervent prayer of — Lewis

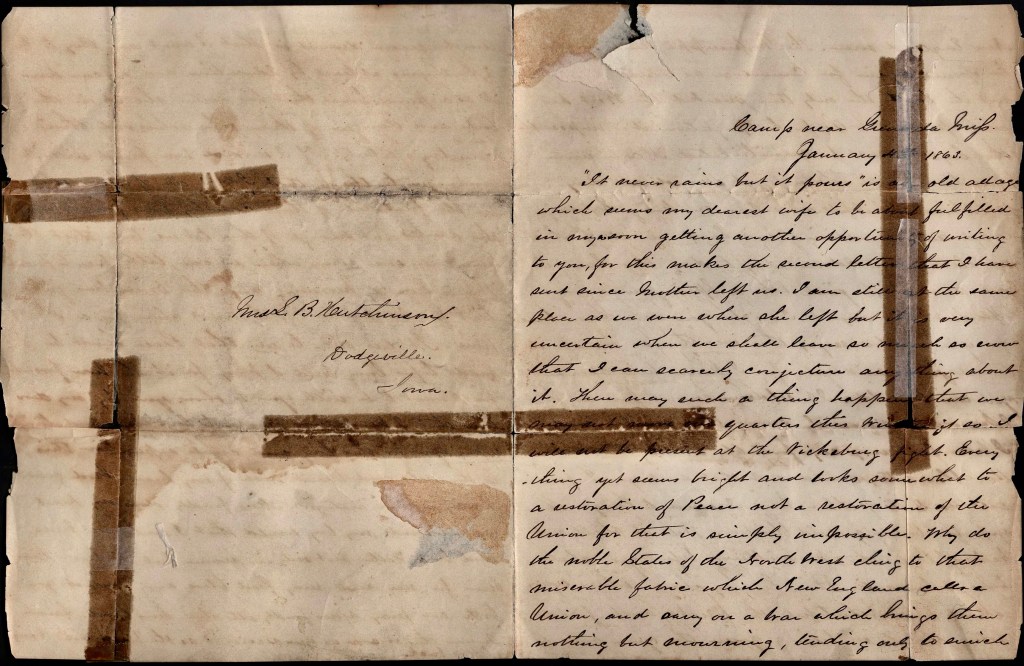

Letter 4

Camp near Grenada, Mississippi

January 4, 1863

“It never rains but it pours” is an old adage which seems, my dearest wife, to be about fulfilled in my soon getting another opportunity of writing to you for this makes the second letter that I have sent since Mother left us. I am still at the same place as we were when she left but it is very uncertain when we shall leave, so much so now that I can scarcely conjecture anything about it. There may such a thing happen that we may not move our quarters this winter. If so, I will be present at the Vicksburg fight. Everything yet seems bright and looks somewhat to a restoration of peace, not a restoration of the Union for that is simply impossible. Why do the noble states of the Northwest cling to that miserable fabric which New England calls a Union, and carry on a war which brings them nothing but mourning, tending only to [ ] New England men. The Mississippi river would be opened again for commerce as usual and is not the South the only true market the West has for its products? As for subjugation, it is impossible. The South must be annihilated; it can never be subjugated.

Yesterday it rained all day and we amused ourselves making sausage meat and rendering out lard in all of which we succeeded admirably. Today the sun is out and it is just like a spring morning. Dearest, how much I wish you were down here for you would enjoy this weather so much. It would just suit you for I know how averse to are to cold. It seldom snows here. In fact, I have not seen any snow this winter and I have been very comfortable at night under two blankets. Would not that suit you? for well do I remember how I used to laugh at you for being so cold-blooded. Well, it shall not be long, Providence permitting, before you shall have a home in this sunny clime where everything is so beautiful—the forests and fields being clothed in living green the year round.

Another reason, dearest, is that I want our boy to be a Southerner, at least by education, and he can have it as a proud boast that his Father shared in the toils and dangers of those who achieved their country’s liberty. If I survive, how proud will It make me to think that I was one of those who on the first call of their country was found in the ranks. But enough of this. Let us hope that the time will soon come when we can talk face to face.

This is Sunday morning and the drum has just beat for inspection so I must close for a short time. It does seem to me that peace must be made before long and I pray for it oh how fervently for I want to be with you to show you, my dear, that I have never ceased to love you and to repay you for this long and cruel separation. This is the only and truest wish of my heart. God grant it may be realized. How fondly does my heart yearn towards my boy. Would that I could see him and be a Father not only in name but in deed. Kiss him for me and may God bless and protect you both. Every pray your fondly attached husband, — Lewis

Answer this as soon as you receive it as the bearer will bring letters back.

Letter 5

December 24, 1863

Dearest Lib,

As I have a chance of writing again, it would be remiss in me not to wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. We are not allowed to tell of our whereabouts so that must be left to your own imagination and what you can gather from the newspapers. I suppose you heard of the affair of the “Chesapeake.” If so, you need not be alarmed for I am safe and well. I cannot tell you now where to direct but expect to have a chance in a few weeks—not only to write, but to receive letters. This will be mailed by a friend. I have only written to let you know that I am in excellent health, not having been sick an hour since I left. I will write again soon and I hope to be able to send you some substantive aid. I wish I could be more explicit. My best love to Father, Mother, and Mary. Kiss Gussie for me. Goodbye as ever. Your husband, — Lewis

Did you get the photographs?

Letter 6

Off Fort Fisher, North Carolina

January 16th 1864

My dear Father,

I only write to tell you that I am safe and unharmed. You will get the particulars as soon as I have time. I have only five minutes to spare. Affectionately your son, — Lewis

Fort Fisher has fallen. Please write to Lizzie.

Letter 7

February 1, 1864

A fine opportunity now presenting itself of sending a few lines to you, my dearest Lib, has determined me upon availing myself of it to assure you that I am not only in the land of the living, but in good health. I inclose you a check for twenty-five dollars which will be made payable to Father. I have done this so as to cause you no trouble about going to the Banking Houses. Small as the sum is, I hope you will not despise it, but accept as an earnest that I have at last awakened to a sense of my duty. I would like to send you more but I can assure you that there is more than two-thirds of all that I have. However, I shall send you more as soon as I am able.

I hope that you are still in St. Louis as I think it so much better for Gussie to be there and also yourself. Not a single letter have I received since I left home. This I can’t account for as I have written and rewritten. You must write as soon as you receive this directing to simply Lewis Hutchinsonm the place to write to will be wherever this letter is mailed as an answer will be waited for & forwarded to me as soon as received.

When you write you must tell me everything—all about yourself and Gussie. Everything will be of interest to one who has been so long cut off from any communication with the loved ones at home.

I am not doing as well as I hoped but still am doing something and hope soon to do better. It may be that in a couple of months or so I will be somewhat nearer you than I now am. I have already said all that I can so I will close. My best love to Father, Mother, and Mary. Kiss Gussie for me. I wish I could do it myself. Goodbye my dearest Lib and believe me ever to be your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Letter 8

U. S. Steamer “Juniata”

August 22, 1864

I was very much surprised and disappointed in not receiving any answer to my letter on my return from a week’s cruise day before yesterday. I wrote you a long letter some time ago, my dearest Lib, telling you where I was and what doing, and have also written to Father & Mother but have received no answer a yet. What is the reason that you don’t write? I told you in my letter that you must be certain to write to the Navy Agent in Philadelphia and draw my half pay which certainly is not much but it is all I have at present.

In case you did not receive my letter, I will repeat that you write a letter to the Navy Agent, Philadelphia, stating that you are my wife by whom I left my half to be drawn and he will let you know how it is to be done. I am expecting a few dollars and should it arrive before I leave, I will send it to you. Did you receive the fifty dollars sent more than two months ago? I am quite anxious to hear in reference to it.

We will probably sail in a few hours for a cruise of eight or ten days and then return here to fit out for Europe and I do hope and pray that there may be some news from home for me. I hope, my dear wife, that you are in good health and spirits adn that you find in Carter a great comfort & solace. Kiss the dear boy for me and tell him he must be obedient to his Mother and Grandparents and not forget his Father. Love to Father and Mother and thank them for their kind care of you and Carter. Tell them I will write again in a few days. Love to Mary adn last but not least I want you to write me a long letter telling me about everything that has and is occurring. Goodbye my dearest wife, your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Letter 9

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe, Va.

August 26th 1864

My dear Parents,

I cannot leave this country on a long an maybe dangerous cruise without writing again to you, although I have written so often lately not only to you but to Lizzie and have received no answer that I almost despair of ever hearing again. When we were at sea, often during my lonely watch on deck, have the events of my past life crowded through my thoughts and I have seen them in all their enormity and shuddered to think how guilty I had been. Can you my parents for give me for the many griefs I have caused you and for the many bitter tears I know my Mother has shed for me? Better would it have been had I died in my infancy. The demon of intemperance has been at the bottom of it all, but now it has no charms for me. I have utterly and entirely forsworn the cup and I draw my dollar and a half monthly instead of the grog ration. What I have been doing since I left home I would rather tell you if we ever meet again than to write it as I much fear my letters do not always get into the right hands.

The ship will more than probably leave here this week for a cruise around the European shores and may go to China. Thus you see I may be absent for nearly two years and I think it is better so. The crew are of the better class of men, most of them Southern sympathizers who have taken this method to avoid the draft into the Army. The discipline is very strict and there is generally plenty to do. From where we are laying, I can see the spires of Norfolk and I have seen the skeleton of the Cumberland as she lays off the Navy Yard. How forcibly every day these sights remind me of Talcott and I wish that I could have been what he was—the soul of honor and courage. I cannot be too thankful to you for your kind care of Lizzie and Carter and hope that you will still look after their welfare until my time of probation is up when I hope to return a wiser, better & steadier man.

Forgive me for all my wrong doings. Write to me and give me words of encouragement to lighten my dark path and if I am wrong in being where I am, it was almost starvation that drove me here. Write to me often and direct to this steamer, Washington D. C., and the letters will find me. Please send me a paper occasionally. Oh how I long to hear from the dear ones at home. [Brother] Ran[dolph] I have heard nothing about for some time. I have but little more time to write as our mail is nearly ready to go ashore.

Tell Lizzie that I will try and send her a few lines tomorrow or next day. A kiss for Mary. Carter, I hope, is behaving himself and is doing well. Mother must kiss him for me. Goodbye my dearest parents and do write soon to your affectionate son, — Lewis

Letter 10

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe, Va.

October 5th 1864

We arrived here only last night from a fourteen days cruise in search of blockade runners and you can hardly imagine, my dearest Lib, my disappointment and astonishment when on the mail bag being opened, there was no letter from you. Lizzie, this is very strange and to me unaccountable. If you have determined not to write to me, I think you might inform me of the fact so as at least to rid me of this longing and expectation. Lib, my dear wife, I know that I have not done by you as I should and during the hours of my lonely watch during the hours of the night, have thoughts of you come crowding through my mind and deeply have I regretted my course in life and my conduct towards you and with God’s help, I have determined to do better. Now dearest, don’t dampen my good resolutions by your silence leading me to think that you are trying to blot me from your memory. Heaven send that this is not the case as I do love you from the bottom of my heart of hearts.

We cruised around the ocean and picked up a cotton bale that had been in all probability thrown from a blockade runner which was chased. This was the result of all our labor. We encountered one pretty severe gale which lasted about twenty-four hours and the next morning when I came on deck, I was surprised to hear the twitter of birds and on looking up in the rigging, saw a large number of shore birds that had ben blown off and taken refuge on board with us. No one would harm them but the poor little fellows died one by one either from fright or exhaustion.

I hope and pray that the War is nearly over so that I can settle down somewhere never to move again. Politics do not trouble us much but we are pretty generally in favor of McClellan. I hope you get the half pay regularly. It is little, I know, but all that I can at present do. It is reported on board that we are to go to Wilmington, North Carolina, where there is a very severe battle expected and I may not get another chance to write before I go. So if anything happens to me, you will at least have heard from me whilst I was still unhurt.

And now how is my dear boy? Is he well? and does he grow both in mind and body? Oh how I long to see him and hear his sweet prattle again. Heaven bless and preserve him and make him a better man than his Father. Now, my dear wife, I must close my letter for I can say no more. If you would only write, I would in all probability write a longer letter but this one sided correspondence is very hard to sustain. I only beg that if you do not intend to write to me or if my letters are a nuisance that you would tell me so and then I would know how to act. Relieve me from this suspense, I beg of you. Goodbye my dear Lib. May God help and protect you and my boy and may we all be restored to one another and happier days. Kiss Gussie for me and do write soon. Direct as this letter is headed. Every your fondly attached husband, — Lewis

Letter 11

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe

November 6th 1864

You cannot imagine my dearest Lizzie with what feelings of delight that I perused your long expected letter which arrived yesterday. Indeed, I had given up all idea of ever hearing from you personally again on account of your long silence. But now the ice is broken, let it not freeze up again but write to me regularly at least once every two weeks at any rate. I shall expect to hear from you that often.

“Business before pleasure” is an old motto so I will commence with that. I saw the paymaster of our ship yesterday and he told me that he had orders to stop all half pay allowances until the men were out of debt. You see we had to draw a large lot of clothing for sea service which is charged against us. Well, I drew the whole amount at once thinking that I would work it out by half pay but it seems that it is different. The half pay allotment will continue again the first of next January when you will receive it regularly as I have clothes sufficient to last some time and what I am compelled to draw will not amount to much. You must not think that I am extravagant for really and truly I have not had a dollar in my pocket for more htan two months.

We are still lying at Fortress Monroe but expect to sail this week for the place I have mentioned before. I do wish it was over for really I don’t want to go at all but hope and pray that I may be spared yet a little longer. So Gussie says he is a “good Union boy?” Bless his sweet little mouth. I wish I could kiss him and his Ma too. I suppose he does not remember me at all or if he does, it is only a very faint idea of who I am. You ask me dearest if I am very hungry. I can answer yes—very often, for sea fare is very rough and I often long for a good shore meal. But I will not repine but try and bear up as best I may. Won’t it be a blessed thing if this winter should end the war and I could come home again in the spring. You know not how I wish that I could be with you. Well, I have no more to say—only to beg of you to write to me frequently. Kiss Gussie for me and may Heaven bless you both, my dearest wife. Goodbye. Ever your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Direct to U. S. Sloop of War “Juniata”—not “Juricata”. Fortress Monroe, Va., or elsewhere.

November 9th. Your letter of the 5th has just been received which I will answer soon.

Letter 12

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe, Va.

November 20th 1864

I have sat down to write you my weekly letter, my dear wife, to let you know that I am still in the land of the living. You see that i am still at the old anchorage and from all indications am pretty certain that it is decided that we are to remain where we are during the winter. I do not like this much as I am afraid we will suffer from the cold but for the reason that I will be nearer you where I can hear from you more regularly it is bearable. So far we have had very pleasant weather and have no reason to complain.

Yours of October (without date, has been on hand since Tuesday last and has been read more than once, I can assure you. I have written to you explaining the reason of the stoppage of the half pay and can assure you that it will commence as soon as possible without any further hindrances. You do not wish, dearest, more than I do that we were settled down somewhere in a home of our own and if this war would only be settled, something of the sort might happen. But as it is, one cannot tell if their bread is their own for five minutes at a time.

You say that you wish I would become a minister. This I think will never happen, but I may become a good Christian. I have made a number of resolutions that I am doing all in my power to live up to. Now can’t you aid me with your prayers and in turn, I beg of you to become a good and consistent member of the Church so that our boy will have an example in his Mother and oh! dearest, don’t let him go to bed at night without clasping his infant hands in prayer for Christ expressly says, “Suffer the little ones to come unto me for such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” Lib, I do not blame you for complaining for I know you have the right, but I am trying to be more as I ought and I want you to assist me with your advice and prayers.

You can’t imagine how pleased I was to hear that Gussie still remembered me. Kiss him for me and tell him that his Pa will come to him someday. I hope never to be separated. When you write, I want you to tell me all about his sayings and doings and also about yourself as such letters are most interesting to me. I send you enclosed a stamp and a copy of a prayer that my Mother learnt me when an infant and I want you to teach it to our boy. Direct me as usual. I have no photograph but will try and send you one soon. Wrote soon to your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Goodbye.

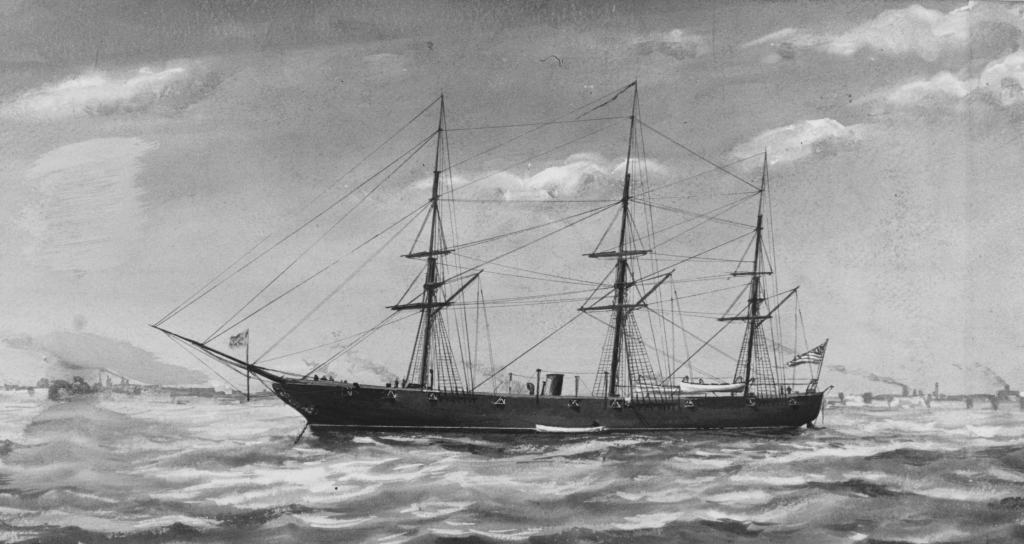

Letter 13

U. S. Steamer Juniata

Fortress Monroe, Va.

November 27th, 1864

I am again seated, my dearest wife, writing my regular Sunday epistle to you and although I have received no late news from you, I will try and make myself as interesting as possible. You see that we are still at the same place and I hope that we may remain here as I have no liking for any more adventures either by flood or field. Indeed, my longing the fixed wish of my heart is now to have a home no matter how small where in the bosom of my little family I might live in peace and quiet and at the same time acquire an honest livelihood providing for the education of my boy. Indeed, dearest, you know not how my conscience upbraids me for my past life and the many miserable hours I spend thinking over the past and trying to reform Heaven I know will lend me aid and I hope yet to become all that may be expected of me. But I will not weary you with this kind of talk but will try and let my actions prove the truth of my words.

I will send you in my next, I expect, my grog money which will not be much but will go to prove that I am at least in earnest. We are having as a general thing beautiful weather, varied with an occasional cold snap for a day or so, then clearing off finely. I am almost inclined to think that the signs of the times bode peace at no very distant day. God grant it may be so as I have seen enough of the horrors of war. Lincoln’s election seemed to carry the idea of four years more of war but yet I think there is some chance for a settlement of our internal difficulties.

Try and write as often as you can, my dear Lib, for I long for your letters. Kiss my dear boy and give him the enclosed twenty-five cents for me. Let him get anything that he likes with it. God bless you dearest. Your affectionate husband, — Lewis

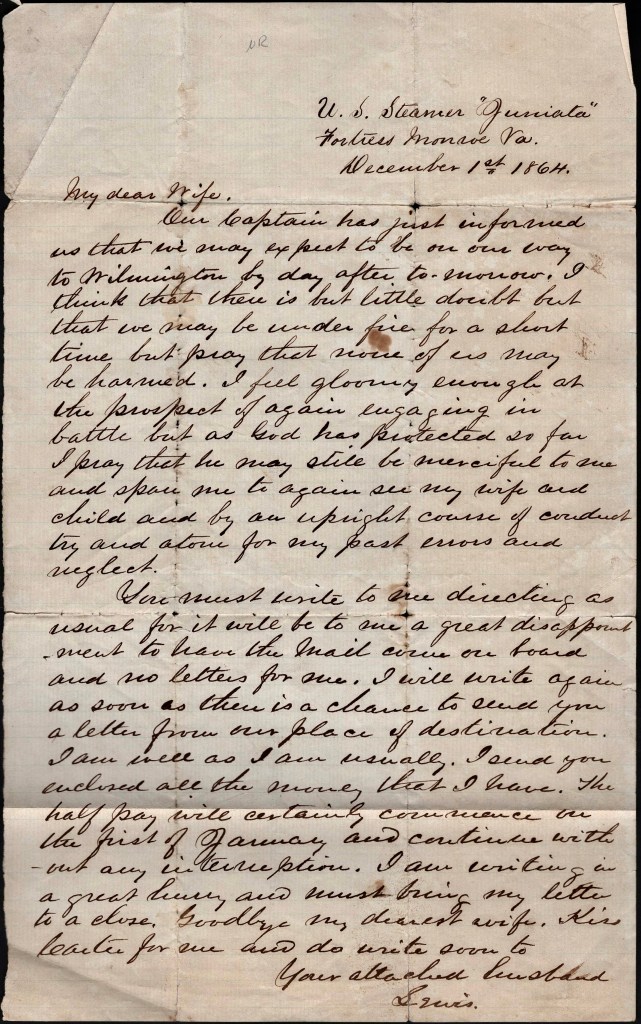

Letter 14

U. S .Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe, Va.

December 1st 1864

My Dear Wife,

Our Captain has just informed us that we may expect to be on our way to Wilmington by day after tomorrow, I think that there is but little doubt but that we may be under fire for a short time but pray that none of us may be harmed. I feel gloomy enough at the prospect of again engaging in battle but as God has protected so far I pray that he may still be merciful to me and spare me to again see my wife and child and by an upright course of conduct try and atone for my past errors and neglect.

You must write to me directing as usual for it will be to me a great disappointment to have the mail come on board and no letters for me. I will write again as soon as there is a chance to send you a letter from our place of destination. I am well as I am usually. I send you enclosed all the money that I have. The half pay will certainly commence on the first of January and continue without any interruption. I am writing in a great hurry and must bring my letter to a close. Goodbye my dearest wife. Kiss Carter for me and do write soon to your attached husband, — Lewis

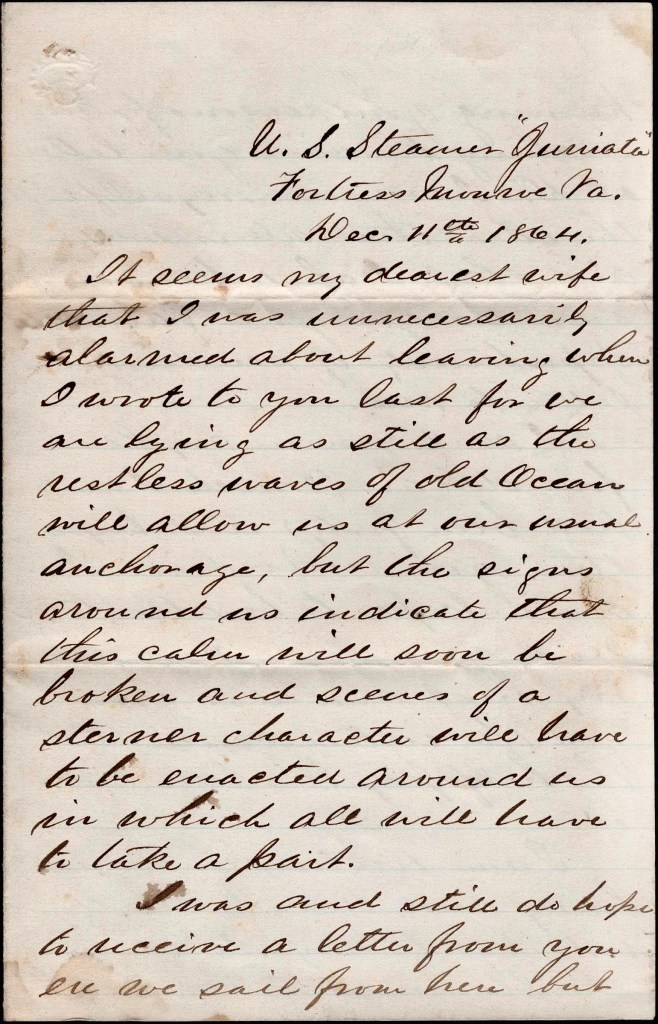

Letter 15

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Fortress Monroe, Va.

December 11th 1864

It seems my dearest wife that I was unnecessarily alarmed about leaving when I wrote to you last for we are lying as still as the restless waves of old Ocean will allow us at our usual anchorage, but the signs around us indicate that this calm will soon be broken and scenes of a sterner character will have to be enacted around us in which all will have to take a part.

I was and still hope to receive a letter from you ere we sail from here but knowing your reasons for not wishing to mail your letters at “D” [Dodgeville], I console myself with the idea that all is well and that I shall hear as soon as you get a favorable opportunity of sending a letter to me.

I sent you in my last four dollars (which I wish had been forty) and hope that you received it. I am in hopes to be able to send you some more in my next and also give you the intelligence that the half pay has been renewed.

I am writing in a great hurry and have little of interest to say so wishing the blessing of Heaven upon you and my dear boy. Write soon and as often as you can. What did Carter do with his quarter? Goodbye. Your affectionate husband, — Lewis

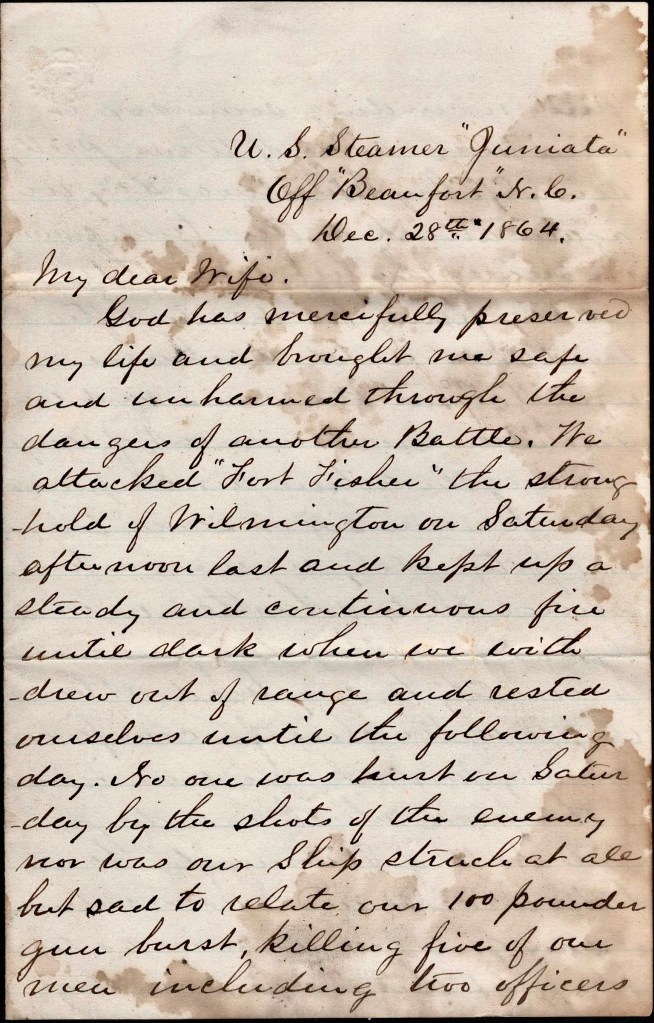

Letter 16

U. S. Steamer “Juniata“

Off “Beaufort” North Carolina

December 28th 1864

My dear wife,

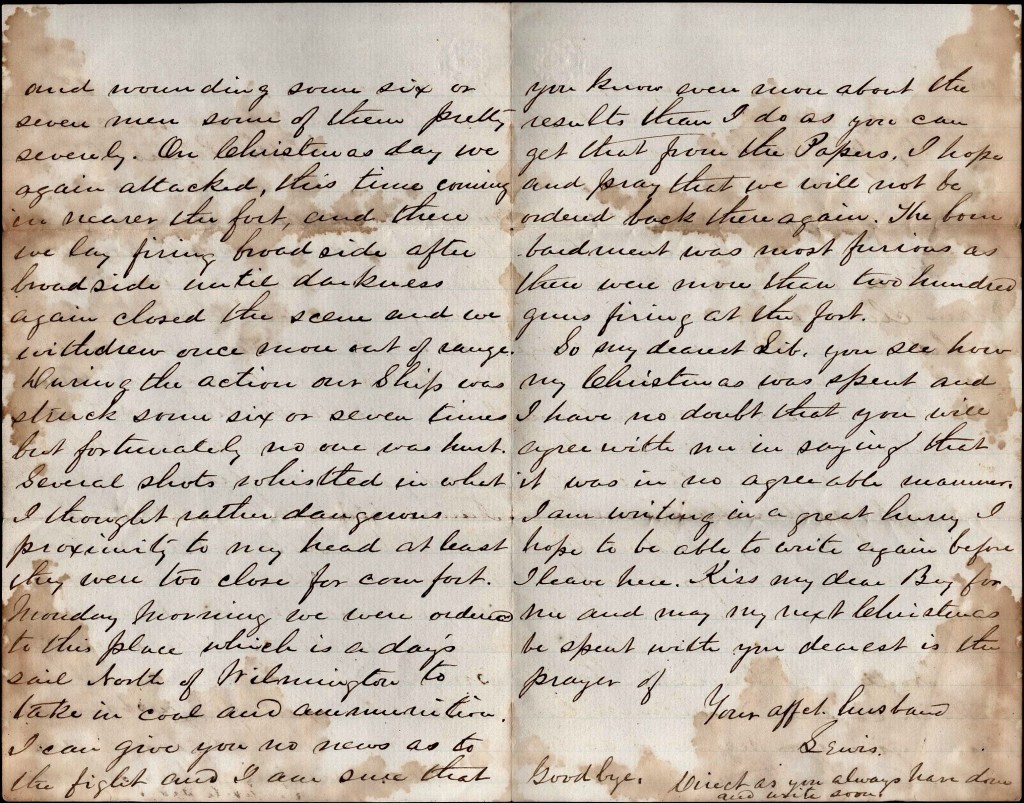

God has mercifully preserved my life and brought me safe and unharmed through the danger of another battle. We attacked “Fort Fisher” the stronghold of Wilmington on Saturday afternoon last and kept up a steady and continuous fire until dark when we withdrew out of range and rested ourselves until the following day. No one was hurt on Saturday by the shots of the enemy nor was our ship struck at all but sad to relate our 100-pounder gun burst, killing five of our men including two officers and wounding some six or seven men, some of them pretty severely.

On Christmas day we again attacked, this time coming in nearer the fort and there we lay firing broadside after broadside until darkness again closed the scene and we withdrew once more out of range. During the action our ship was struck some six or seven times but fortunately no one was hurt. Several shots whistled in what I thought rather dangerous proximity to my head—at least they were too close for comfort.

Monday morning we were ordered to this place which is a day’s sail north of Wilmington to take in coal and ammunition. I can give you no news as to the fight and I am sure that you know even more about the results than I do as you can get that from the papers. I hope and pray that we will not be ordered back there again. The bombardment was most furious as there were more than two hundred guns firing at the fort.

So, my dearest Lib, you see how my Christmas was spent and I have no doubt that you will agree with me in saying that it was in no agreeable manner. I am writing in a great hurry. I hope to be able to write again before I leave here. Kiss my dear boy for me and may my next Christmas be spent with you dearest is the prayer of your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Goodbye. Direct as you always have done and write soon.

Letter 17

At Sea off “Beaufort” North Carolina

January 5th 1865

As I have a little time to spare, I thought I would devote it to you, my dear Lib. We are still at anchor lying off “Beaufort” but are ready for sea at a moment’s warning. We have had no correct accounts as yet of our engagement at “Fort Fisher” but know enough to be certain that we did not take it and have but little doubt that before another week is numbered with the past that we will have o renew the attack and more lives will be taken ere the deed is completed. This war is a cruel, murderous business.

I presume that before this time you have received my letter announcing my safety during the last attack and you can be assured by this that I am still in good health. Yours of the 11th of last month (no, I am mistaken, it was dated the 23rd) came to hand day before yesterday and was received as a drop of water to a thirty man. I trust that Gussie has entirely recovered and will be shielded by a mother’s care and prayers from hearing that badness which you seem to think he is liable to. Often my dear wife, do I regret my former course of life and think with bitterness of the past and am and will do all that poor human nature can to reform and make atonement for the past. You know not the privations and hardships of a sailor’s life but I will not complain as I deserve them all.

So Gussie says he is “going down to Dixie to fight the Yankees.” God spare him from ever having to mingle in the horrid scenes of war. Kiss him for me and tell him his Pa thinks often of him and longs for a sight of his dear face.

I am glad you received the money and hope to be able to send you some more in a day or two and the monthly half pay. Direct to me as usual and write soon & often as you can. God bless you prays your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Letter 18

U. S. S. “Juniata“

Bull’s Bay, South Carolina

February 17, 1865

Although I have written so recently I still flatter myself, my dearest Lib, that a short note from me will prove acceptable. We are still in the same place as when I wrote last but are momentarily expecting a move somewhere. The greater portion of the crew have been ashore for the last four days. What they are doing is still involved in mystery, but we can shrewdly guess that it is to aid in some demonstration on Charleston. Our ears have been saluted during the whole morning with the report of cannon in the direction of Charleston and we judge from the rapidity of firing that something serious must be going on.

February 19th 1865. I stopped writing day before yesterday, dearest, on account of the scarcity of anything to say. Today I can give you the glorious news that Charleston is in our possession. I say glorious because it is my opinion the greatest step towards peace that has yet been taken, and with the declaration of peace comes the true and genuine hope that I may be with my family without any fear of molestation.

I saw the paymaster the other day and he promised me that the half pay should commence so that you could draw for February. I am waiting his movements with all due patience and don’t think I will close this letter until I can tell you that all is right. Good night dearest. A kiss for Gussie and as many as you like for yourself.

Off Charleston, S. C., February 20th 1865. We are lying in plain view of the much dreaded “Fort Sumpter” and can easily distinguish the steeples and large buildings in the City. Our steamers are busily engaged plying to and fro in places where one week ago it would have been madness for them to be. As yet, I have no particulars to relate and only know the fact of its being in our possession. You will probably gather more from the papers than I will know for some time. I hope and pray my dear Lib, that this may bring the war to a speedy conclusion for it looks to me like that it were worse than folly for the South to attempt to hold out any longer. But at the same time I am free to confess that it galls me to the quick to think that they will be subjugated.

Well, after all the delay, the deed is done and you can write immediately to the Navy Agent at Philadelphia so that you can draw the money for February. You understand how to proceed so that I cannot advise you on that subject. Noe I do hope my dearest wife that nothing can possibly occur to interrupt you in receiving this money regularly—at least if it does, it will not be my fault. Do write me a long letter soon and tell me all the news. Does Carter grow much? and what does he talk about? Does he learn anything in the way of reading? Is he an apt scholar? In fact, tell me all about him and you can tell him with a kiss that his Pa often thinks of him and wishes himself at home. Again I repeat, write as soon and often as you can. Do you ever hear from St. Louis? God bless you both prays yours affectionate husband, – Lewis

Letter 19

U. S. S. “Juniata“

Off Charleston, South Carolina

February 27, 1865

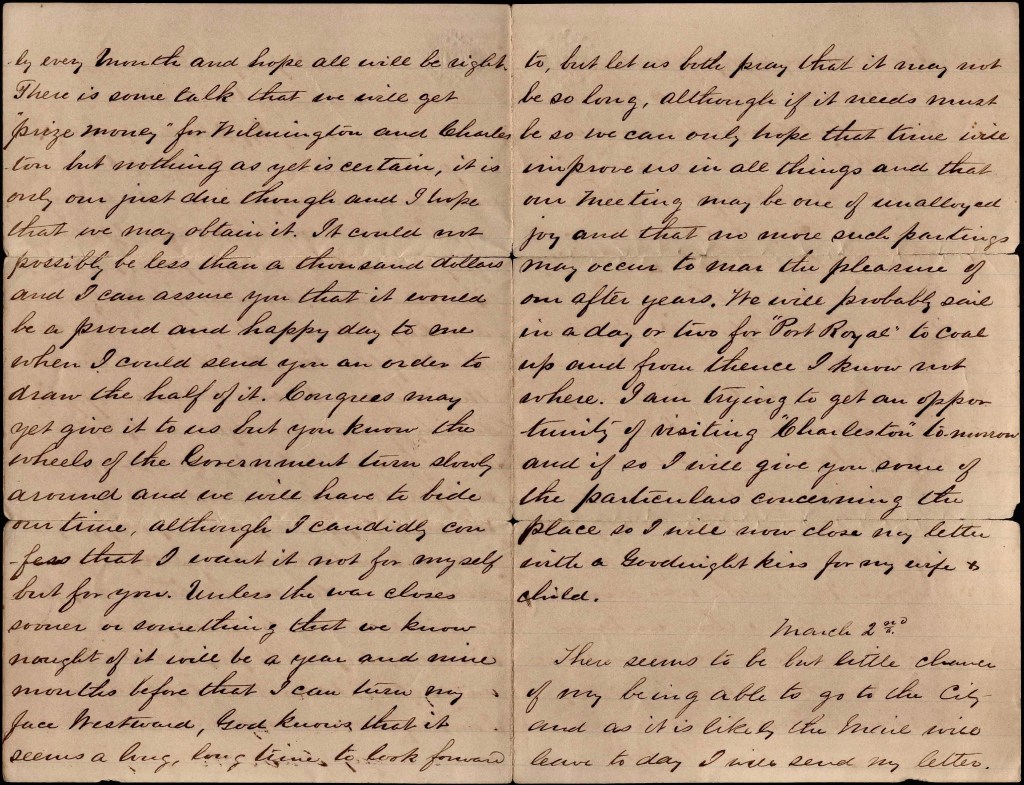

I am about to commence a letter to you, my dear Lib, tonight but when I shall finish it I will not now attempt to say. The latest news that I have had of you and Carter was a letter from Mother dated the 7th of this month in which she says that “you and he were well.” I would like to hear from you more frequently but do not blame you in the least for your discretion. I sent you word a few days ago to write on immediately for my February half pay and hope that ere this you have received the letter and written on. If there is any failure in receiving the money, write to me immediately as the pay is deducted from me so that it can be rectified at once. I know of no cause now that can be made an excuse for your not drawing it regularly every month and hope all will be right.

There is some talk that we will get “prize money” for Wilmington and Charleston but nothing as yet is certain. It is only our just due though and I hope that we may obtain it. It could not possibly be less than a thousand dollars and I can assure you that it would be a proud and happy day to me when I could send and order to draw the half of it. Congress may yet give it to us but you know the wheels of the government turn slowly around and we will have to bide our time, although I candidly confess that I want it not for myself but for you. Unless the war closes sooner or something that we know naught of, it will be a year and nine months before that I can turn my face westward. God knows that it seems a long, long time to look forward to, but let us both pray that it may not be so long. Although it needs must be so, we can only hope that time will improve us in all things and that our meeting may be one of unalloyed joy and that no more such partings may occur to mar the pleasure of our after years.

We will probably sail in a day or two for “Port Royal” to coal up and from thence I know not where. I am trying to get an opportunity of visiting “Charleston: tomorrow and if so, I will give you some of the particulars concerning the place. So I will now close my letter with a goodnight kiss for my wife and child.

March 2d. There seems to be but little chance of my being able to go to the City and as it is likely the mail will leave today, I will send my letter. Write to me by every opportunity as it is a long time since I have heard from you. Kiss Carter for me and goodbye. Your affectionate husband, — Lewis

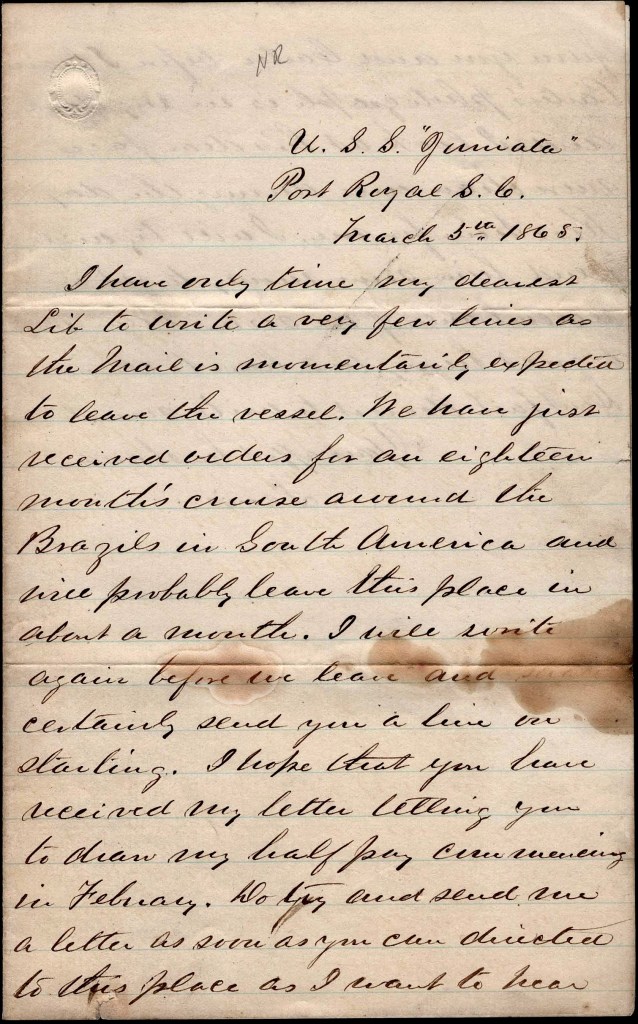

Letter 20

U. S. S. “Juniata“

Port Royal, South Carolina

March 5th 1865

I have only time my dearest Lib, to write a very few lines as the mail is momentarily expected to leave the vessel. We have just received orders for an eighteen month’s cruise around the Brazils in South America and will probably leave this place in about a month. I will write again before we leave and certainly send you a line on starting. I hope that you have received my letter telling you to draw my half pay commencing in February. Do try and send me a letter as soon as you can directed to this place as I want to hear from you and Carter before I leave. Carter’s photograph is in my desk and look at his dear face more than once during the day. Kiss him for me, I will try and send him some money to get a remberance of me soon. I am in a great hurry and have to close. Don’t fail dearest to write soon to your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Letter 21

U. S. Ship “Juniata“

Port Royal, South Carolina

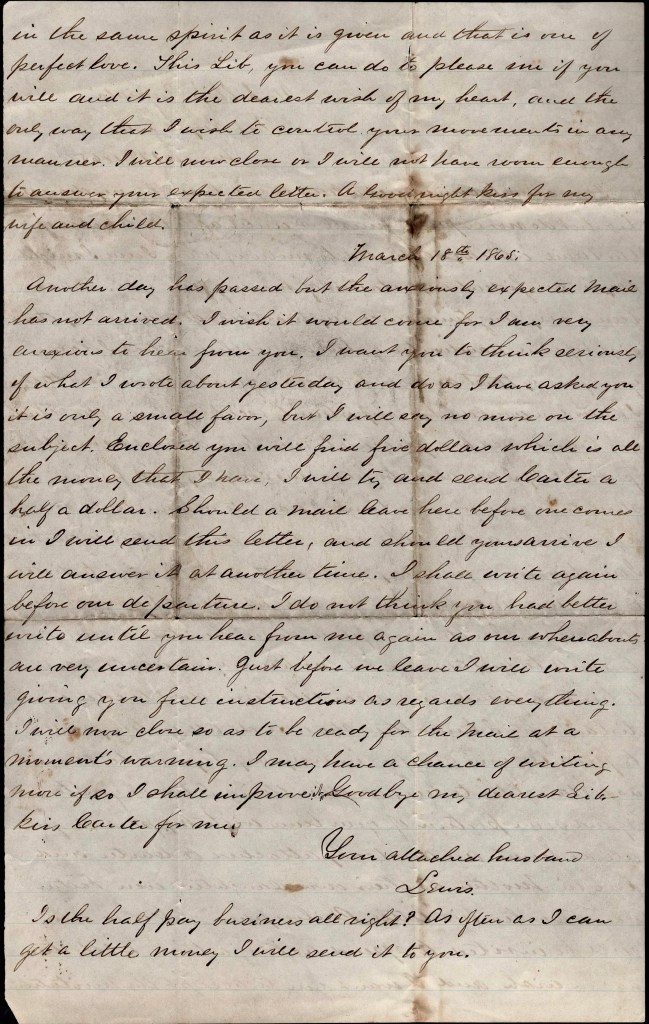

March 17th 1865

I am about to commence a letter to you tonight, my dearest Lib, but do not expect to finish it until after the arrival of the mail, which is expected tomorrow, when I am I might say in confident expectation of hearing from you. It has been a very long time since my heart was gladdened by the sight of your handwriting, but do not think that I blame you, for my trust and confidence in your love is so great that I know you would let no opportunity escape of doing that which you know would be a pleasure to me. Now dearest, as in all probability I am about to leave this country for a foreign shore to be gone for some time, I want to ask you to do me a few favors, and at the sane time so not think that I am trying to find any fault with you or wish to dictate to you in a manner that you might think harsh or unreasonable. In the first place, do not hesitate a moment to write to Mother and let her know your wants. Write to her as a friend and near relation. Don’t be cold or distant for I know that she will do all in her power to promote your comfort in every way. Try and be more as a daughter to her.

Another thing, I want you to spend some portion of your time with my parents for all at home are devotedly attached to Carter and love his Mother as their own daughter. Even father calls Carter his “little philosopher.” I know you will be invited to spend as long a time with them as you wish and I want you to accept the invitation in the same spirit as it is given and that is one of perfect love. This, Lib, you can do to please me if you will and it is the dearest wish of my heart and the only way that I wish to control your movements in any manner. I will now close or I will not have rom enough to answer your expected letter. A goodnight kiss for my wife and child.

March 18th 1865. Another day has passed but the anxiously expected mail has not arrived. I wish it would come for I am very anxious to hear from you. I want you to think seriously of what I wrote about yesterday and do as I have asked you. It is only a small favor, but I will say no more on the subject. Enclosed you will find five dollars which is all the money that I have. I will try and send Carter a half dollar. Should a mail leave here before one comes in I will send this letter and should yours arrive, I will answer it at another time. I shall write again before our departure. I do not think you had better write until you hear from me again as our whereabouts are very uncertain. Just before we leave, I will write giving you full instructions as regards everything. I will now close so as to be ready for the mail at a moment’s warning. I may have a chance of writing more. If so, I shall improve. Goodbye my dearest Lib. Kiss Carter for me. Your attached husband, — Lewis

Is the half pay business all right? As often as I can get a little money, I will send it to you.

Letter 22

U. S. S. “Juniata“

port Royal, South Carolina

March 28th 1865

My dear wife,

I am only about to write a few lines as I am somewhat pinched for time. I have just received a letter from Mother who is now in Philadelphia where she has accompanied Mary to school and where she will remain until fall probably. As soon as you receive this, write to me at once directing your letter to Mother at No. 1200 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. You can put two envelopes on if you wish, one directed to me, the other to Mother. I am getting very anxious to hear from you once more as it has been a very, very long time since I have heard from you. Tell me about the half pay if all is right in that quarter. Did you receive the money I sent you in my last? I will try and send you as much more soon. Believe me dearest, I do not spend a cent for my own personal gratification—only buying just what I am obliged to and all that I can get I will try and send you. Kiss Carter for me and tell me what he said about the little letter I sent him. I have only written to beg you to write immediately. Goodbye. Your affectionate husband, — Lewis

Letter 23

April 12th

We were all mistaken yesterday. That was not the mail steamer but she is hourly expected and I hope that your long looked for letter ay arrive. It is rumored now that we will sail by the 7th of next month which I hope may be true as I am getting tired of lying here doing nothing and I think that time passes away more rapidly when we are on the move.

Yesterday afternoon I was out with a party of the men fishing or hauling a seine. We were only tolerably successful but I had quite a nice mess of fish for my supper. I was in the water constantly for nearly three hours and must confess that I do not feel any better for it this morning. While we were away, Mr. [Gustavus V.] Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, came into Port and there was considerable noise made over him in the way of burning gunpowder. The news has reached us of the fall of Richmond. God grant that the war may be speedily closed. My dearest wife, the mail has come and no letter for me. I am sick at heart and can write no more. Goodbye. Kiss my boy for me. Is it any use to ask you to write soon to your attached husband, – Lewis

Letter 24

U. S. S. “Juniata“

Port Royal. South Carolina

April 26th, 1865

Your letters of the 10th, my dear wife, enclosed to Mother has just been received and I will not delay a moment in answering it. I feel very much concerned in reference to Carter’s health, but hope now that he has recovered from the measles that he may become more settled as regards his constitution. I hope and trust that it is only a Mother’s fears that make you think him delicate. I am glad he was pleased with his letter and will try and send him another before I leave. I sent him some time ago a little hymn book and by the same mail with this send him a Little Prince. Tell him he must know how to read before I come back and he must learn the hymns I marked so as to say them off by heart.

I do not know what to think about your losing all your teeth. You must find out what a good false set cost and I will do my best to send on the money for them as soon as possible—even if it should come by driblets. There will be no necessity of the half pay being stopped as I am ahead on my accounts & nothing but the most unwarrantable extravagance on my part could reduce them so as to make such a thing necessary. Southwest Missouri has always been the place where I have longed to settle down in and when I return, I shall wend my steps in that direction if nothing occurs to prevent. They tell me that in Brazil there is a splendid opening for Civil Engineers, the salaries amounting to 4 and 4 thousand dollars a year. As this is my profession, I shall look into the matter and it it proves favorable, we may go there to live. But of this, more anon. How would you like to be transferred into a Spanish domaine? It is very probable that three weeks may yet elapse before we sail and I shall write by every mail.

Dearest, you told me not to send you my grog money fearing that I might stint myself. This is like your generous disposition, but I feel happier in sending it to you than in keeping it myself. I get my board, such as it is, and the few luxuries that I would buy would not be any compensation. It has been a long time since I have seen your dear handwriting and your letter has been read more than once. Forgive me if I have written anything that may seem harsh.

The death of the President is a hard blow to all—both North and South—as I believe that he was the right man in the right place and was doing all in his power to alleviate the sufferings of all. I hope that the murderer may be caught and dealt with as he deserves and I pray that the South may not be dealt more harshly with on account of the action of one man who could have been little better than a maniac.

Orders may arrive to prevent us from our cruise but of this I have little hope and have about settled down to the conviction that I must go. You must cheer up, dearest, for when I come back, I want you to look as handsome as ever for I shall come back to stay—that is, we are not to be separated again. In reference to the likeness, I am sorry to say that there is no chance about here for such a thing but I will certainly send you one just as soon as I can. Kiss Carter for me and write soon to your attached husband, — Lewis

Goodbye.

Letter 25

U. S. S. “Juniata“

Port Royal Harbor

May 24th 1865

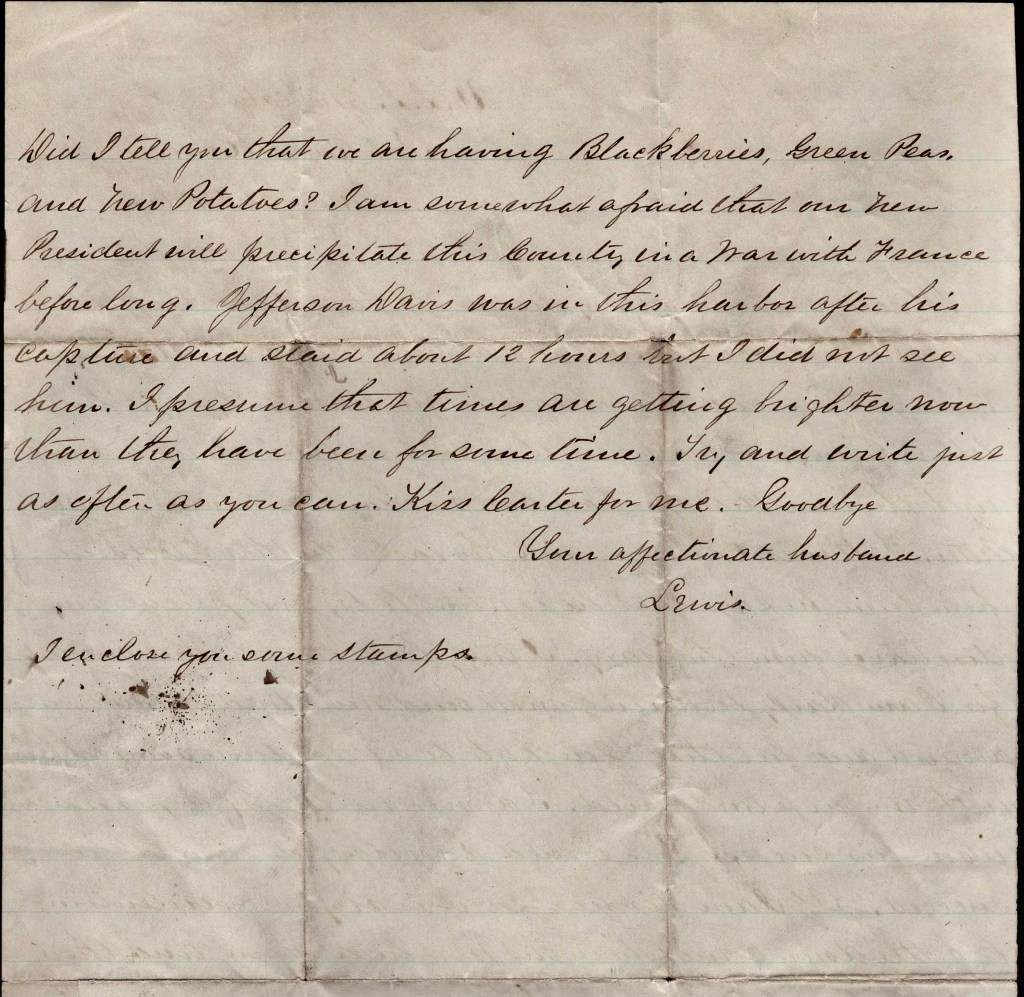

It really seems to me, my dearest Lib, that I am keeping up a one-sided correspondence, as your letters, like Angel’s visits, are few and far between. I am constantly expecting letters from you but when they don’t arrive, I console myself with the idea that you have had no chance of sending me a letter. Father is East now and the last letter that I received from him he says that he is about to try and procure my discharge from the Navy. I truly hope that he will succeed for I am daily becoming more and more tired of wandering around and feel that I ought to be settled down somewhere with my wife and child. I do not build my hopes much upon his success but would be overjoyed should he succeed. If I am discharged, it is my firm intention to settle down somewhere out West on a farm and there establish a home for us. I presume that I ought to hear something in refernce to this matter by the first of next week but I am patiently waiting the result. Do you think that you could forgetting the past thus settle down with me in love and peace? and tell me truly do you love me as much as you did when we were first married? Dear little Carter, I hope, has fully recovered and is as good and sweet as ever. How I long to hear his childish prattle. What did you think of the likeness? I was almost ashamed to send it but was afraid that I could not get another so concluded that it would have to go. Did you receive the last five dollars I sent you?

Did I tell you that we are having blackberries, green peas, and new potatoes? I am somewhat afraid that our new President will precipitate this country in a war with France before long. Jefferson Davis was in this harbor after his capture and stayed about 12 hours but I did not see him. I presume that times are getting brighter now that they have been for some time. Try and write just as often as you can. Kiss Carter for me. Goodbye. Your affectionate husband, — Lewis

I enclose you some stamps.

Letter 26

U. S. Steamer “Massachusetts” at sea

June 14th 1865

My dear Lizzie,

I am on my way to Philadelphia and am once more a free man. My discharge came yesterday, I shall make only a short stop anywhere until I see you, just long enough to settle about the future. Keep this news to yourself. Don’t be surprised but hold yourself in readiness to join me at a moment’s notice. I will write again from Philadelphia. I don’t know that you need write until you hear from me as I am not certain that I will stop long enough to receive a letter. You will not of course receive the June half pay but me instead. How do you like the change? Don’t let anyone see this letter. Keep mum. A kiss for Carter and love for you from your fond husband, — Lewis

Griff, Nice piece of very detailed research into Lewis Hutchinson’s life and times. What a character to behold! Thanks again for all your amazing work with these letters. You really bring history to life!

Cheers Rob, FNQ,Au

LikeLike