The following letter was written by Edgar W. Irish (1838-1897), the son of George Irish (1810-1888) and Maria Edgerton Potter (1810-1844) of Little Genesse, Allegany county, New York. Edgar enlisted in Co. C, 85th New York Infantry with his younger brother George Hadwin Irish in September 1861. Edgar was made a corporal upon mustering into the regiment and was promoted to sergeant in April 1862. His beautiful penmanship no doubt earned him the rank of 1st Sergt. in August 1862—his highest rank.

In April 1864, while garrisoning the forts at Plymouth, North Carolina, both Edgar and his brother George were taken prisoner with approximately 500 others when the town was surrendered. He and George were sent to Andersonville Prison, George. A source on Find-A-Grave claims that Edgar’s fine penmanship and bookkeeping skills earned him a job at the prison that enabled him to be kept separately and fed better than his fellow prisoners. All the while, however, he worried about his younger brother and after months of pleading, he was finally allowed to search for George but found that he was too late; George had passed away the day before of starvation and dysentery. Edgar was determined that the truth would be known about Andersonville, and seek revenge for his brother George. He found records and concealed them on himself when he was released from prison. Later this evidence was used at the trial of Capt. Wirz. Along with George 310 Soldiers from the 85th died as prisoners of war, the most men of any unit in the Northern Army. George Hadwin Irish is buried at Andersonville National Cemetary, Sumter County, Georgia, USA Site#4587, Findagrave Memorial#28873296.

There is a cenotaph in Edgar’s name at the West Genessee Cemetery that has the following inscription carved into the base: “He made, preserved and supplied the evidence that made possible the execution of Capt. Henry Wirz. The keeper of Anderson Prison.”

Transcription

Camp Shephard

Washington D. C.

December 12th 1861

Dear Cousin Lottie,

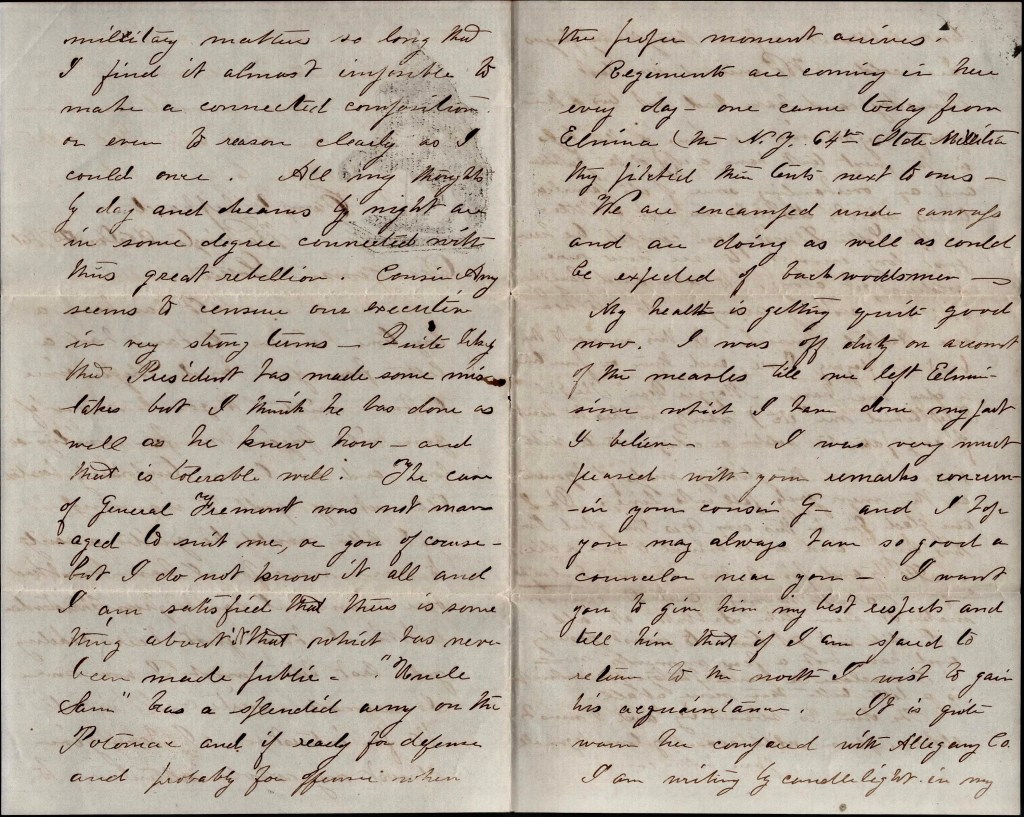

It has been a long time since I have had a letter from you and longer since I have written to you. Now if you will forgive me for waiting so long and as I am temporarily located, I’ll set my quill to running. A letter would be quite a rarity to me now for I have not had one since I came from Christendom. Lottie, I have just been reading your last letter and I am sure I cannot write one to match it for interest. I have give almost my whole attention to military matters so long that I find it almost impossible to make a connected composition or even to reason clearly as I could once. All my thoughts by day and dreams by night are in some degree connected with this great rebellion.

Cousin Amy seems to censure our [Chief] Executive in very strong terms. Quite likely the President has made some mistakes but I think he has done as well as he knew how—and that is tolerable well. The case of General Fremont was not managed to suit me, or you of course, but I do not know it all and I am satisfied that there is something about it that which has never been made public. 1

“Uncle Sam” has a splendid army on the Potomac and if ready for defense and probably for offense when the proper moment arrives. Regiments are coming in here every day. One came today from Elmira (the N. Y. 64th State Militia). They pitched their tents next to ours. We are encamped under canvas and are doing as well as could be expected of backwoodsmen.

My health is getting quite good now. I was off duty on account of the measles till we left Elmira, since which I have done my part, I believe. I was very much pleased with your remarks concerning your cousin G. and I hope you may always have so good a counselor near you. I want you to give him my best respects and tell him that if I am spared to return to the North, I wish to gain his acquaintance.

It is quite warm here compared with Allegany Co. I am writing by candlelight in my tent without a fire though my fingers are cold. We arrived here last Thursday and have had but two or three frosty nights since. Some of the boys in the next tent have a copy of the Jubilee and an overhauling some of its familiar tunes which disturb me not a little.

Oh Lottie, I wish you could be here just long enough to see how our soldiers get along, to see and laugh over our cooking arrangements, to hear our martial music (at this moment the band is playing Dixie, and three or four times a day we have “Maggie Dear,” “The Girl I left behind me,” etc.) which makes the heart of every patriotic soldier or citizen thrill with joy, to see the glittering mass of bayonets as the men gaily fall into line. Oh, I am glad I’m in this army. Yes, I’m glad I’m [in] this army,” and we’re bound to win or die.

I’ll try and finish this tomorrow, Good night.

Sabbath morning, and I cannot make it seem like Sabbath at all. I did not get time to finish yesterday and have but a few moments now. I enclosed a card photograph which is a little better than none at all. The drum is sounding and I must close. Please write soon. My love to you all. Your brother cousin, — Edgar W.

1 In August 1861, General John Fremont imposed martial law in the state of Missouri and declared all rebel owned slaves to be free. Lincoln, fearing the loss of a loyal border state, rescinded Fremont’s order and relieved the General of his command.