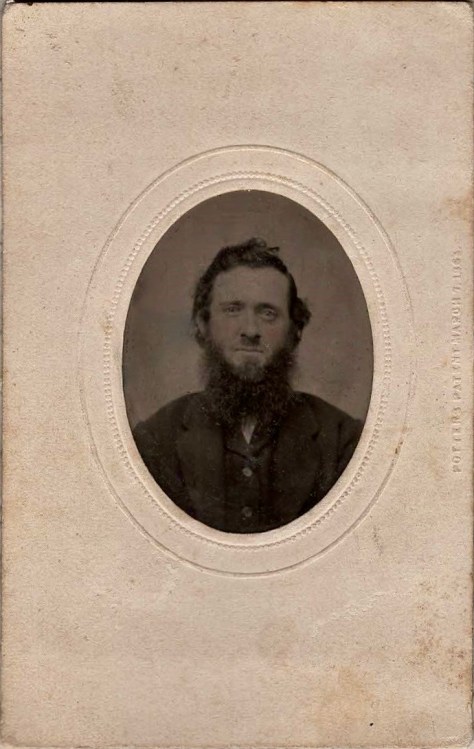

This letter was written by Constant (“Con”) Crandall Hanks (1821-1871), the son of Uriah Hanks (1789-1871) and Florilla Howes (1803-1890) of Shandaken, Ulster county, New York. Con was married in 1852 to Hannah L. Reynolds (1818-1881) and was the father of at least four children when he enlisted at the age of 41 on 13 September 1861 as a private in Co. K, 80th New York Infantry. He was promoted to corporal two weeks later.

In this correspondence, composed from a hospital in Falls Church, Virginia, Con informs his mother of the arduous march through the relentless rain and mud, endured with his regiment to the vicinity of Bull Run and back, which exacerbated his already infirm leg. He concludes the letter by indicating that the regiment will soon embark on transports alongside other troops as they head to the Peninsula; however, he may be sent home by the surgeons due to his disability. Yet, his muster roll records reveal that he remained in service, participating with his regiment in the Battle of 2nd Bull Run, where he was wounded on 30 August 1862, and again at Petersburg on 3 April 1865. Ultimately, he was mustered out of service in September 1864, having completed his three-year commitment. The 1870 census indicates that Con, along with his wife and two children, resided in Hunter, Greene County, New York, where he was employed at a chair factory.

Con’s penmanship and composition suggested a better than average education and I found that he had attended the Troy Conference Academy in 1841. The Academy was a co-educational institution affiliated with the Troy Conference of the Methodist Church.

Transcription

Falls Church, Fairfax Co., Virginia

March 23, 1862

Mother,

I remember well when I was a boy when I used to knock off a toenail, cut my finger, have any sore, how I used to go to you to do up the wounds, how it used to ease the pain to fuss over the sores and have you sympathize and feel sorry and bad over them for me. It used to take more than half the pain and soreness away when I had your sympathy, which I always was sure to get however unworthy it might be. My old sprained leg, with its sores and pains, has almost daily for the last 4 weeks forced the memory of my boyhood days of your love & untiring kindness & sympathy back fresh on my mind. And as I am now driven into the hospital on account of my leg & not having but little to do to occupy my mind & time, I took it into my head that if I wrote to you to let you know now I was, engage your sympathy as I used to have it when a boy, that like as not the cursed old sprain would get better just as my sore toes and fingers used to get better with your sympathy when a boy.

Now, for my story, you must pretend to feel bad whether you do or not. Well to begin with, a week ago last Monday, the great machine that makes what is called the Army of the Potomac was put in motion. For the last fortnight before that, I had been excused from duty on account of my leg, but when the orders came to march, I said “go in leg.” So I put on my traps with the rest of the regiment, two days rations with the other equipage makes in all some 60 lbs. Well we commenced our march for Centerville & Bulls Run with sanguine hopes of there finding the D__d Rebels and renewing the acquaintance that proved so disgraceful to our boys the 21st of last July, and having a chat with them on more equal terms than we had the last time there.

Well, as we began to march, the rain began to come down. The further we went, the harder the rain came—mud some 6 inches deep. Thus we marched that day in rain & mud some I6 miles and encamped in a bit of wood some 3 miles this side of Centerville. We had our tents on our backs. Maybe we wasn’t glad to throw off our knapsacks, pitch our tents, and build fires to dry our clothes. Maybe the rail fence did not make good fires—but I guess they did. Maybe my old sprained leg did not thank Gen. Wadsworth from the bottom of each sore that it was not obliged to march any farther that day. Maybe the sea biscuit, though hard as a piece of crockery eaten with a piece of raw pork did not taste good that night, but my opinion is that they went down with good relish.

Well, we stayed in that camp which we called Camp Disappointment till Saturday. We called it Camp Disappointment because 50,000 men of us started in the strength of God & all the munitions of war for Centerville and Bulls Run to square up with the Rebels that account that was opened with them last July. The balance then was against us and we had started Monday morning with the purpose—“God willing”—to pay up that balance and all the interest that has been gathering on it since the account was opened & you may rest assured that we would have done it, for there was no cowards that morning. Many a poor fellow that had just come out of the hospital shouldered his knapsack and was as eager for the fight as the strongest, but when we came to Centerville—the great stronghold of the rebels, behold! they had gone. Gone too as if the devil was after them, leaving what they could not move. They left there forts [and] breastworks that might have given [us] some tremendous hard fighting before we could have got the place. But it appears that they remember Bulls Run as well as we do and probably that the taking of Roanoke [and] Donelson had inspired them with the proper respect for Uncle Sam’s boys that is good for their health.

They left a good deal of their provender behind. They set fire to a good many 100 barrels of flour and 1000 bushels of grain so they should not fall into our hands. It looked dismal round their encampments. They had wooden huts to quarter in, shingled much more comfortable than we had. As many of our regiment as wanted to, had permission to go and view the battle ground of Bull Run. I was foolish enough to go, but mother, it was a sad sight. There was a good many of the 14th Brooklyn that was killed in that battle. The Rebels just dug a ditch and pitched [them in]. Some they covered, some they did not. The Brooklyn boys wore red pants that day and you could see many skeleton legs with remnants of the red pants on them. The 14th went out and gathered all they knew by the red pants and buried them but they could not find one skeleton that had the head on. It seemed as if the devils had cut the heads off both wounded and the dead.

Friday we went to Bull Run & Friday night they sent a messenger after us to return to camp and march on Saturday morning. We started Saturday morning from Bulls Run to camp, a distance of ten miles. Then we took 9 of them hard biscuits and a piece of raw pork for two days rations, put on all of our traps and commenced a march towards Alexandria and we marched 18 miles farther—rain harder, I never see it, but we marched on, and still on. We never stopped long enough all day to unsling our knapsacks and [it] rained all night. We camped down on the wet ground, nothing over us but them little hen coop tents. Then did not poor sprained leg cry out for mercy all night as we lay there in the wet. Did it burn and throb as if they was a blister drawing all over it. I never slept one wink. Don’t believe I would if I was in heaven.

The next morning there was five nice biles [boils] or ulcers on my leg from my ankle up to my knee. We was ordered back to camp on that Sunday morning. I had two of them hard crackers for my breakfast. Had to march 9 miles on that. I think that I can fully appreciate the feeling Esau had when he sold his birthright for a mess of pottage [lentil stew]. I would have given my soul for a loaf of bread that morning and could not get it. God knows I was sore and faint when I got to camp. I have not done any duty since. Am in the hospital. Whether I ever shall do any more duty, don’t [know]. The brigade surgeon said today that they would send me home but I don’t want to come home till Old Jeff Davis gets justice done him.

The regiment was marched again on Tuesday. They are encamped a mile and [a half] from where we have been lying all winter. Some 80,000 men are being shipped down the Potomac. Our regiment are waiting their turn to go aboard. They probably will go today. Where they go, McClellan knows. I don’t. Oh, how I wish that my leg was so that I could go with them. I should be happy. But to be stuck here in the hospital makes me miserable. Pity my old leg, Mother, as you used to when I was a boy which I would jam a toe or finger. Then I guess it will [be] well again.

I got a letter from Hannah urging on me the duty of prayer. I wonder if she thinks that it is of more use for me to pray now than it was when I used to pray in my family when she would tell me that my prayers did not go higher than my head, I learn that Brother Cyrus has found the pearl of price. I hope that he is not a hypocrite as he charged me with being once when I trusted in a Savior’s love. Mother please accept my love for yourself and all my friends. You need not write till you hear from me again for I don’t know how soon I may move from here.– Con Hanks

Griff, An excellent read! Thanks for the wonderful transcription.

LikeLike