The following letters, heartfelt and poignant, were penned by Clark Callender (1834-1899), the son of Silas Callender (1805-1880) and Mary Carkuff (1805-1879) from Fairmount, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. Addressed to his parents, these letters revolve around his younger brother, Thomas Callender (1839-1863), who valiantly served as a private in Co. F. of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Gettysburg. Tragically, he was mortally wounded at the railroad cut in front of McPherson’s Barn. Within these letters, Clark recounts the distressing moment when their neighbor’s son, Pvt. Clark Woodworth, was struck down. As Thomas rushed to assist him, he faced the heartbreaking reality that Woodworth felt he could not endure. Thomas himself was then grievously injured, a bullet piercing his sternum and tragically passing through both his body and bronchial tube before exiting through his clavicle. In a somber twist of fate, he was carried to McPherson’s barn by Confederate soldiers.

Later Thomas was carried to the St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church in Gettysburg where Sister Camilla O’Keefe, a member of the Sisters of Charity, wrote, “The Catholic church in Gettysburg was filled with sick and wounded … The soldiers lay on the pew seats, under them and in every aisle. They were also in the sanctuary and the gallery, so close together that there was scarcely room to move about. Many of them lay in their own blood…but no word of complaint escaped from their lips.” Yet another woman, a Gettysburg resident who volunteered as a nurse named Sallie Myers, wrote: “I knelt beside the first man near the door and asked what I could do. ‘Nothing,’ he replied, ‘I am going to die.’ I went outside the church and cried. I returned and spoke to the man — he was wounded in the lungs and spine, and there was not the slightest hope for him. The man was Sgt. Alexander Stewart of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers. I read a chapter of the Bible to him; it was the last chapter his father had read before he left home.”

Clark’s letters provide a daily chronicle of Thomas’s fluctuating condition, reveals the brother’s agonizing search across the battlefield, the tension of doctor visits, and the heartbreaking deception he felt compelled to navigate—informing his father that Thomas held no hope of survival, while quietly offering their mother a glimmer of reassurance that he might yet endure. Thomas died on 23 July 1863, over three weeks after he was wounded. Heartbreakingly, Clark Woodworth’s body was never recovered, leaving him listed among the unknowns—a somber reminder of the war’s toll on families.

[Note: Photocopies made from the originals of these letters were provided to me for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by Wayne Rizor, a descendant of the Callender family.]

Letter 1

Gettysburg [Pennsylvania]

Saturday noon

To Mother,

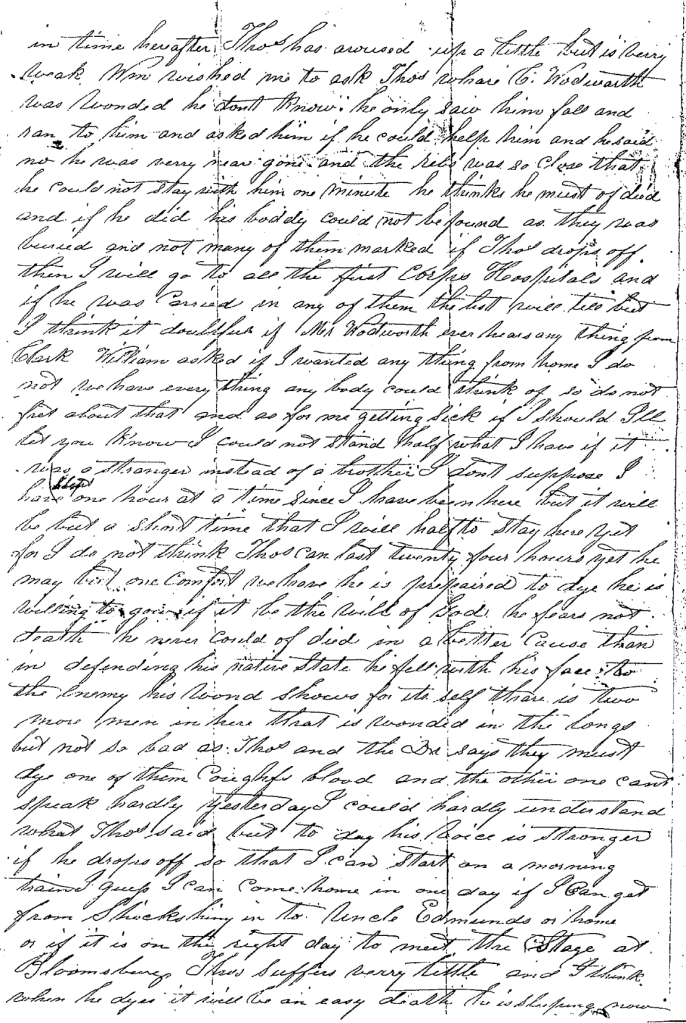

Thomas is sleeping and so I will write a few lines. When he sleeps, the times so long. Yesterday I moved him on another bed where he has a good place. He is more by himself. I wish I could tell you that I thought Thomas would get well, but I do not. He may live some days yet and he may die any hour. He has lived longer than any of the doctors thought he could. I got the doctor to examine him a little while ago and I asked if since he had lived so much longer than any of them expected if there was no chance for his recovery and he said if he would live one month yet, he would not have any more hopes of him. If we can’t have him anymore with us, we ought to be thankful that we have the privilege of being with him to see to his wants and to know that he is a going to a better world where we meet him again. He does not bleed much anymore. Last night I felt of his hands about eleven o’clock and he was cold up to his elbows and his legs and feet up to his knees. I could hardly feel any pulse. I gave him some wine and then rubbed him and got. the blood to circulating again. He is now about the same as he has been for the last two or three days.

There are a good many dying here for the want of care but you. may rest assured that Thomas gets good care. I say candidly, I believe he is better off here than he would be at home. Here he can have everything he can wish for and doctors here all the time to watch every change. His appetite is middling good. He eats bread, dried peaches, and tea and oranges mostly. He sleeps a good bit now. At first I had to give him morphine to make him sleep.

I have just been out to the battleground where he was shot to see if I could find his knapsack but could not. I have got canteen and haversack, or it is the canteen that he has when the Rebels went into the barn where he lay. They took his canteen and left him have theirs. You can form no idea of what property is destroyed where two such armies meet and fight as they did here.

Mr. Harrison is a little better. His son and daughter is here taking care of him—his daughter in the daytime and his son at night. I lay close by Thomas and some nights I can sleep some and some I do not but watch my chance in the daytime when he is asleep and lay down and take a nap so I can do right well.

The Boys was a dirty-looking set of fellows but it is no wonder. They had marched twenty-one days through the dust and then went right into the fight. I have washed Thomas every day since I have been here but he is not clean yet and now he is so weak I do not wash him more than I can help. If I thought none of my folks cared enough for Thomas or me to write, I would not like it but think they have but they have not come. I have not heard from Elizabeth and Johnny nor any of you. And maybe you do not hear from me but if you do not, it is not my fault for I write every day.

There was a man died here this morning with the yellow jaundice. He was as yellow as saffron. Last evening there was one soldier stabbed another in the neck so that he died this morning here in Gettysburg. There is one man in the hospital with nine ball holes in him and he is getting well.

Sunday, 10 p.m. Thomas is no better. I cannot see that he is much weaker this morning. It is strange how he lives as long as he does. The doctors have all of them been disappointed but you may think as he was a strong man he may stand it yet. But I tell you, if he had not of been, he would not lived as long as he has. The constitution must wear out. He bears it very patient. I don’t think I ever heard him complain of anything. When he talks about dying, he is as calm as if he was at home and going out to the barn for something. He told me last night he wanted to be buried in his black clothes and if you have no shirt for him, you can send and get mine for him. He cannot last but a very few days at most. He says he is a going to meet a brother and sister in a better world. He wants Mr. Montgomery to preach his funeral sermon.

I asked him last night if he wanted any of his folks to come and see him and he said he was not particular for they could do him no good. He suffers no pain. I saw a Rebel man die here this morning and there is one of our wounded in here that is crazy. All. that is in here now are badly wounded. The rest have been sent off to a General Hospital.

You need not be uneasy about me. I am well. If Thomas drops off, I will get him embalmed and then you can keep him a month if you wish. The expense of getting him embalmed and the whole expense of getting him home will not reach thirty dollars, my expenses included. I don’t think but he will want a better coffin when I get him home than I can get for him here.

Sunday night, 10 o’clock. I wish I could say to you that there is a change in Thomas for the better but I can see none. At first when I came here, I thought if he would live a week or two, then he would get well, but the longer he lives, the more certain I am that he can’t get well. Last night the Dr. told me he would not live 24 hours and he is alive yet. This evening I got another doctor to examine him and he said he might live two or three days but thought not.

Thomas has got a higher fever tonight than he has had since I have been here. He is comfortable but very flighty. He sleeps a good bit. Dr. Barrett has just been in to see him. He says he can’t get well. I am glad that it has been my lot to be with him and to know that he is a going to a better world where war shall never come. It is a hard sight to see some of our men after they have gave their blood for us and then pass into another world unprepared for eternity. But such is not the case with your son and my brother. We have very kind doctors to take care of him. They do everything I want them to do.

I don’t [see] as you can read what I write. I am sitting close by Thomas and have a little board on my lap to write on and then to help it, somebody has stole my pen and holder and I have a very poor one—one of the soldiers that lay close by Thomas I have took care of since I have been here. Yesterday he was moved off to some General Hospital. I helped him out into the ambulance and then he told me he had left some things that he could not take with him and said I should get them and keep them. I went and this pen and some tobacco and a gum blanket which I feel proud of. I don’t know as he thought of it. I went out to see him but they was gone so I shall keep it.

I don’t know which way I will come home. I heard this evening that there was a bridge broke down between here and Harrisburg and maybe I will have to go by Philadelphia. I hope not. The State will wend Thomas and me home free. I guess Dr. Barrett will stay until I go home. I hope he will.

Every church and school house and court house and a great many dwellings are filled with suffering humanity in and around Gettysburg—a great many to be crippled as long as they live. Some with legs off and some arms off but the greatest number with legs off. It does not seem much like Sunday here. Tell Elizabeth if you see her I am well.

Monday, 5 a.m. I can see no particular change in Thomas this morning. I think I can see that he is failing. He has had another chill this morning. He is got over it now. I think he cannot last long. They are carrying another man out dead now. It beats all. What a sight of men have died in here since I have been here. As fast as one dies, another is brought in. — C. Callender

Monday afternoon. Now father, I will tell you one thing which I did not want to put in the other paper for fear Tommy might want to see it. I do not want to discourage you but suppose you want to know the truth of Tommy’s case. I will tell. you what the doctor told me today. We have got a new doctor and he said his case would prove fatal but I still think he will get well. He is better than he was when I came here. He said the ball had passed through his lungs but I don’t think it is so because if it had, he could not breathe easy and if it did, we often hear of the lungs being decayed.

It is well I did put this on a separate paper for Thomas did ask to see the letter. He knows nothing of this paper. Should he get much worse so that I think he will not get well, then I will tell him but now he is sure he will get well and I am about as sure. I want nothing from home. I don’t think I will be at home until sometime next month. If you can possibly hire somebody to help H. Wolf do my work, do so. Jesse Harrison is no better. I will write again tomorrow, — C. Collender

Letter 2

Hospital

Monday afternoon

To folks at home,

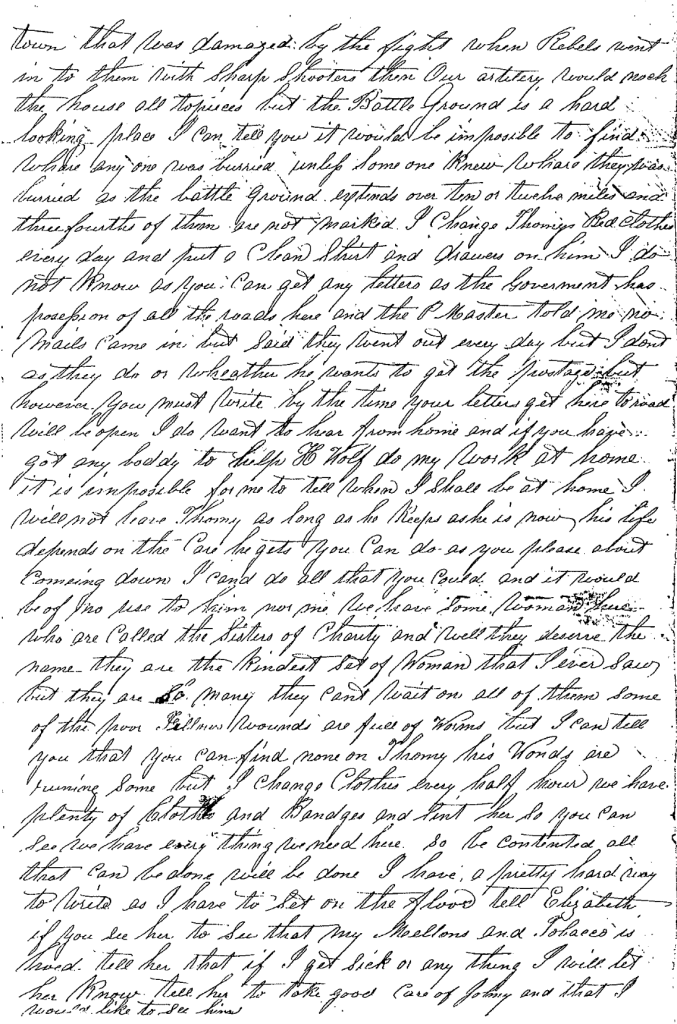

I will tell you how Thomas is this afternoon and then I will tell you again in the morning so I can keep you posted as to his condition. I cannot see any change in him except his wound has got to bleeding a good bit when I raise him up. I have called all the doctors to see if it cannot be stopped and they say I need not be uneasy about that. It is good for him. It is kind of blood and water. His appetite is good enough. He could not sleep very well [so] I got the doctors to give me some sleeping powders for him and now he sleeps about half of the time and so I can keep him from taking so much that is not good for him as it tends to weaken hum. You may think I will make him sleep too much but I will not tell Mother. She need not fret about him being here in the hospital. I know it would be a satisfaction to have him at home but he is far better off here. We have good doctors and they are right here and can see him all the time. And we have a good house and good beds and everything for him to eat that you can think of. Oranges, lemon, dried peaches, huckleberries, gruel beef, tea, corn starch, wine, tea, coffee and soups of all kinds. He says he is better of here than he could be at home.

When I sleep, I lay right here and have a string fast[ened] to me and then fast to him so he can waken me without speaking. I think a hospital is the most solemn place a man can go. You can see poor Union defenders suffering in every shape possible. That noise I spoke of yesterday they say was cannon down at Frederick City. I could hear it very plain. It is the greatest place I ever saw. You cannot hear any news at all. I have not saw a paper since I have been here nor saw a man that has as I know of.

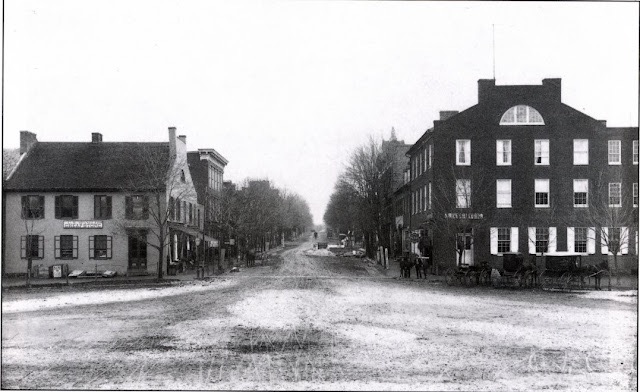

Gettysburg is a very nice place. There is but a few buildings in this town that was damaged by the fights when rebels went into them with sharpshooters. Then our artillery would knock the house all to pieces. But the battleground is a hard-looking place, I can tell you. It would be impossible to find where anyone was buried unless someone knew where they was buried as the battleground extends over ten or twelve miles and three-fourths of them are not marked.

I change Thomas’ bed clothes every day and put a clean shirt and drawers on him. I do not know as you can get any letters as the Government has possession of all the roads here and the Post Master told me no mails came in but said they went out every day. But I don’t know as they do or whether he wants to get the postage. But, however, you must write. By the time your letters get here, the road will be open. I do want to hear from home and if you have got anybody to help H. Wolf do my work at home. It is impossible for me to tell when I shall be at home. I will not leave Tommy as long as he keeps as he is now. His life depends on the care he gets. You can do as you please about coming down. I can do all that you could and it would be of no use to him nor me.

We have some women here who are called the Sisters of Charity and well they deserve the name. They are the kindest set of women that I ever saw. But there are so many, they can’t wait on all of them. Some of the poor fellows’ wounds are full of worms, but I can tell you that you can find none on Tommy. His wounds are running some but I change cloths ever half hour. We have plenty of cloths and bandages and lint here so you. can see we have everything we need here. So be contented. All that can be done, will be done.

I have a pretty hard way to write as I have to sit on the floor. Tell Elizabeth if you see her to see that my melons and tobacco is hoed. Tell her that if I get sick or anything, I will let her know. Tell her to take good care of Johnny and that I would like to see him.

I cant account for it but he is very comfortable. He has no pain nor has not had since I have been here nor is not very sore to be moved. He takes nothing to numb it either. He is in good spirits and thinks he will get well. I think there is no use of any of you coming here. You can do no more for him than I can. If anything should happen that he should not live, I will get him embalmed here in this place and then when I get to Harrisburg, I will telegraph to you and you can get Jacob S. Carey to make him a coffin as I cannot get one here but a box. Now don’t think he is worse because I have wrote this. He is no worse than he was when I came here but his life hangs on a slender thread and no knowing which way it will turn. But I do think you must send William here to take care of Tommy for so sire as he is left alone, he will never get well and I do not believe William could stand it in here where they are taking off legs and arms, and wounds of all kinds. I have stood it well all the time but once. I went to help dress a wound on a man’s arm the other night that had commenced bleeding and he was all blood and still bleeding and I got sick and left. But now I could see a man’s head taken off. I am well and bored with Uncle Sam. I want you to be sure and see that my work is done.

Tuesday morning. Thomas is better this morning than he has been since he has been hurt. I told you above what the doctor thinks of him but I tell you candidly, I do believe he will get well. You had better not come here as I can do all that can be done. He is not very pale and has no pain. He says he could walk and I guess he could. His breast bleeds a good bit but the doctors thinks that is good for him. They say it is what gathers in the wound and if it did not come out, it would kill him. Be sure and write, — C. Callender

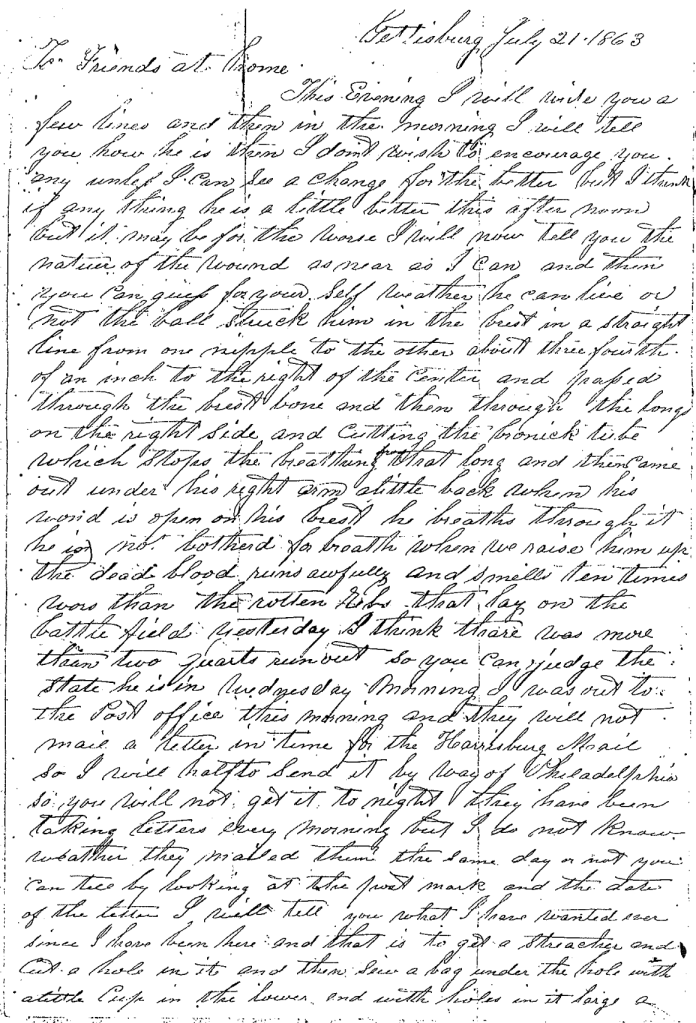

Letter 3

Gettysburg [Pennsylvania]

July 21, 1863

To friends at home,

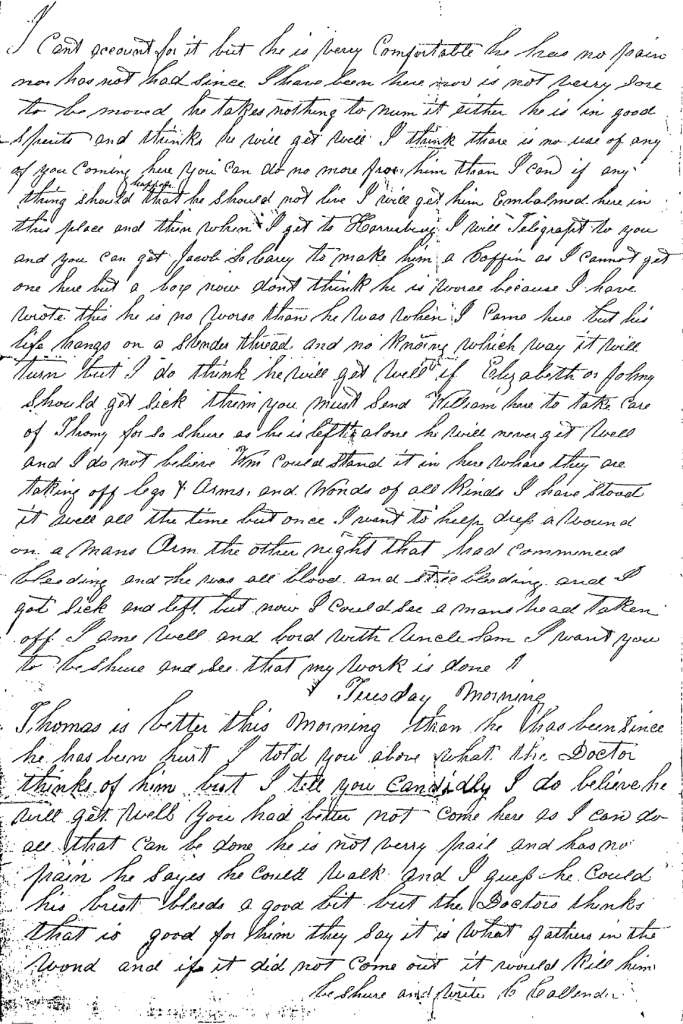

This evening I will write you a few lines and then in the morning I will tell you how he is then. I don’t wish to encourage you any unless I can see a change for the better this afternoon, but it may be for the worse. I will now tell you the nature of the wound as near as I can, and then you can guess for yourself whether he can live or not.

The ball struck him in the breast in a straight line from one nipple to the other about three fourth of an inch to the right of the center and passed through the breast bone and then through the lungs on the right side, and cutting the bronchial tube which stops the breathing for that long and then came out under his right arm a little back. When his wound is open on his breast, he breathes through it. He is not bothered to breath when we raise him up. The dead blood runs awfully and smells ten times worse than the rotten Rebs that lay on the battlefield. Yesterday I think there was more than two quarts run out so you can judge the state he is in.

Wednesday morning. I was out to the Post Office this morning and they will not mail a letter in time for the Harrisburg mail so you. will not get it tonight. They have been taking letters every morning but I do not know whether they mailed them the same day or not. You can tell by looking at the post mark and the date of the letter. I will tell you what I have wanted ever since I have been here and that is to get a stretcher and cut a hole in it and then sew a bag under the hole with a little cup in the lower end with holes in it large enough to let the blood discharge and not let the flies up and then turn Thomas with his breast over the hole and let him lay on his stomach and then that stuff can discharge as fast as it forms in him. I talked with all the doctors and they all say it is of no use. Barrett said the same. But I believe it is the only thing that can be done to help him and maybe that would not. But I think I will try it this morning. If I thought I could get home, I would start this morning but he is too weak. I do not think he is as low as he was yesterday morning but I do. not think he can get well. But it may be he will, but if he does, it will be the strangest thing I ever saw. He is getting very poor in flesh. His appetite is not very good now. He slept good last night. The doctors are beat out at his living as long as he has but they think he cannot get well. But they may be mistaken. They have said for the last eight days that he could not live 24 hours and have missed it every time.

About ten o’clock a.m. There is a change in Thomas. He has another sinking spell. His hands are cold and his pulse has almost ceased to beat, He may never come to again. I do think it would be a fine thing for him if he did not for death is certain and he is so anxious for it to come. I have just talked with the doctor and he says his time is very short. He says there is not a man in here that could of lived half so long as he has with the same wound. I have just received your letter of the 17th & 6 of 16 and was glad to get them for Thomas wanted to hear from home so bad. You must not expect me to write very good for I have to write with a board on my lap and then fan Thomas with my left hand. You will have to do without my letter today, They have made different arrangements. The letters must be at the Post Office in the evening or else they’re not mailed in time for the Harrisburg train. I did not know it in time but will [ ].

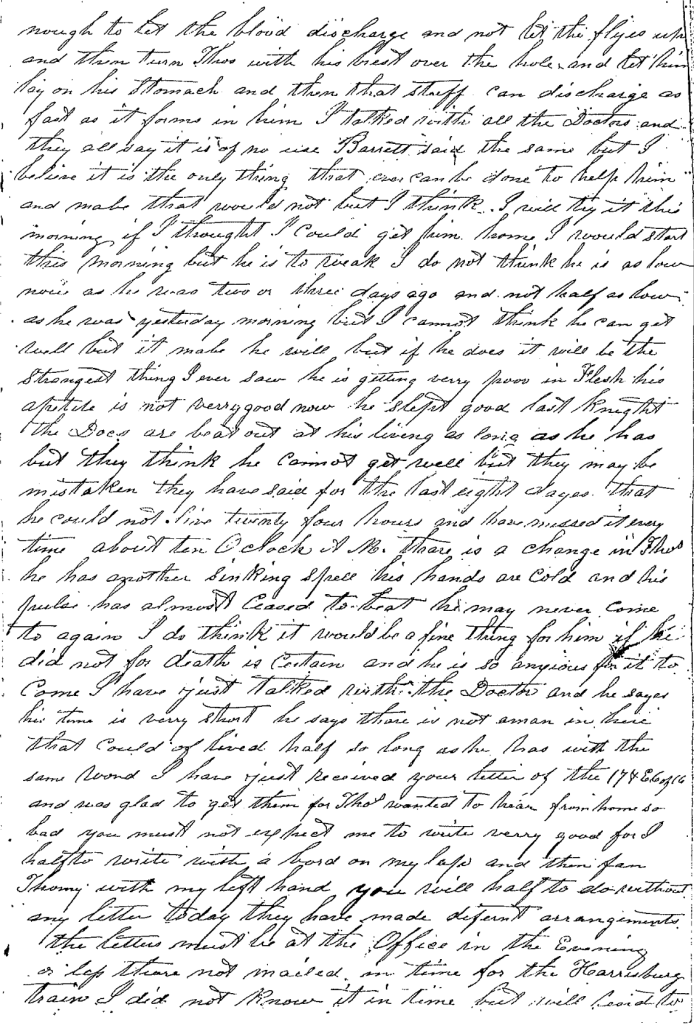

Letter 4

Catholic Church Hospital

Wednesday morning. Tommy is no better. He is failing. His breast continues to bleed so much that he has got very weak. He is very comfortable. He has no pain much. Doctor Barrett & Dr. Erkert from Wilkes Barre was here last evening & they say he is very dangerous. Thomas is sensible of his condition and is calm about it. I asked him if he wanted any of his folks to come and he says he has no choice. They may do as they like. Now you can do as you like, but it is a chance if you can get here in time to see him and if you did, it would do him no good. If it should be that he never gets well, he will add one more to the number of our family circle who have gone to a better world, He is prepared to die. He is very calm and says he is going home.

I do not know which way I will come home if he does not live. If I can’t get anybody to take us to Columbia, I will have to go to Baltimore and them to Philadelphia. I cannot give him up yet but if his lung continues to bleed as it has for a few days, he can’t live. The doctors cannot do anything to stop it. It may be that it will commence healing in time to save him yet. He has everything here to make him comfortable. He could be no better off if he was at home. I do not want anything from home. If I need any more money, Dr. Barrett says I can get it off him. I will write again in the morning. — C. Callender

Letter 5

Gettysburg [Pennsylvania]

Wednesday evening

Dear Father & Mother, Brother & Sister,

This evening I will write a few lines to tell you how Thomas is. He is comfortable. I cannot account for his having as little pain as he has had since I have been here—only that he has lost so much blood. This morning his bleeding ceased and I was in hopes it would not commence again but this afternoon it began again and kept on until this evening. It has stopped but I fear it will commence again. I think it is impossible for him to ever be any better. I thought when I saw him first that he would get well but since that time, his lungs has been bleeding so that he cannot last but a short time. I think we ought to be thankful that he was not among the number that died on the battlefield and his body to be covered without a grave and to be dragged around by the harrows. He is very sensible of his condition and is very willing to die. I have not heard him say once that he would like to get well that I know of.

Ten o’clock. Thomas’ breast has had another bleeding spell but has stopped again and he is asleep. He is very weak. I think he could not live one hour if I did not give him wine. Jesse Harrison is very bad off. You can do as you like about coming to see Tommy. I think it is a great chance if you could get here in time to see him alive and if you did, it would be of little satisfaction to your or him unless he arouses up again which I. think he will not. The railroad communications is open now from here to Carlisle and Harrisburg so that I ought to go home from here in one day if we could connect right.

Eleven o’clock. Thomas is very flighty but has no pain. I wish he would not talk.

Twelve o’clock. He is very flighty but if I speak to him, then he is sensible and says he is going home.

Fifteen minutes after twelve. He has gone to sleep. The blood does not run now.

One o’clock. He is still asleep but is weak.

Three o’clock. He is still a sleeping. He seems a little better.

Four o’clock. He is a good deal better. I don’t know how long it will last. He may get well yet but I guess not. He is flighty some yet. You may look for a letter from here every day as long as Thomas keeps as he is now. Last night I fanned him pretty near all the time. W. Roons & Burnard is here. It does seem as if I see the people in the world is here. Some are hunting friends. Others have come to see the battlefield. I wish that was all that brought me here. You must see that my work is being done if my wheat has to be cut before I get home. I want you to see that the seed is by itself. It is out to the end next to M. Gearheart’s. It runs out toward the turnpike as far as to where there is a stake standing against the fence. You can tell by looking for I have cut the rye out and cockle.

There are about seventy patients in this church. I suppose out on the battle ground in those tents the wounded are not half taken care of like they are here. I do not know where Lee’s army are. We can’t get papers in time. Thomas has aroused up a little but is very weak. William wished me to ask Thomas where C. Wadsworth was wounded. He don’t know. He only saw him fall and ran to him and asked him if he could help him and he said no. He was very near gone and the rebs was so close that he could not stay with him one minute. He thinks he must of died and if he did, his body could not be found as they was buried and not many of them marked. If Thomas drops off, then I will go to all the 1st Corps Hospitals and if he was carried in any of them, the last will tell but I think it doubtless if Mr. Wadsworth ever hears anything from Clark. William asked if I wanted anything from home. I do not. We have everything anybody could think of so do not fret about that and as for me getting sick. If I should, I’ll let you know. I could not stand half what I have if it was a stranger instead of a brother. I don’t suppose I have slept one hour at a time since I have been here yet, for I do not think Thomas can last twenty-four hours. Yet he may. But one comfort we have he is prepared to die. He is willing to go if it be the will of God. He fears not death. He never could of died in a better cause than in defending his native State. He fell with his face to the enemy. His wound shows itself.

There is two more men in here that is wounded in the lungs but not so bad as Thomas and the doctor says they must die. One of them coughs blood and the other one can’t speak hardly. Yesterday I could hardly understand what Thomas said but today his voice is stronger. If he drops off so that I can start on a morning train, I guess I can come home in one day. If I can get from Shock___ in to Uncle Edmunds or home or if it is on the right day to met the stage at Bloomsburg.

Thomas suffers very little and I think when he dies it will be an easy death. He is sleeping now. I cannot hear anything from William Bell and as for the rest of our Boys, they was slightly wounded and have been taken away somewhere so I do not know anything about them. I guess from what I can hear, that there is no danger of Gilbert Callender getting hurt unless he should run against something.

The rebel prisoners appear to be a clever set of fellows. They are ragged, dirty, and I guess lousy—some of them bare headed, and a good many without shirts or shoes. If they could put on a suit of Uncle Sam’s clothes, some of them would be good looking men. Yesterday morning I was down on Diamond Corners and I think I saw nearly one hundred ambulances start out to the different hospitals to carry wounded men to the depot. The Catholic priest is here very busy talking to the soldiers this afternoon. Now I will stop until this evening.

Thomas is sleeping. He does not eat anything much. It will make it a little bad for you that the letters must lay in the post office here over night and that makes about twelve hours later news for you. I do not think Thomas will be living when you get this. I think he will not last until the sun rises again but he may last several days. But he is low enough to die any moment. I tell you, Father, you have no idea of a hospital like this. Many wives hearing their husband, mothers, their sons, sisters, their brothers have come from all over the North to take care of them, and when they arrive in here, you may judge the feeling when they learn that their friend is remembered among the dead. I hope I may never be called to witness another battlefield.

There are five men in here now who are lying very low. I was down to the Government Office today to see if I could get a pass to send up for you to come down and the man said he had no authority to give such a one but if I insisted on it, he would give me one to go home if I wanted it. I thought I would send it and then you could do as you liked about coming. You can do no good here. It would be no satisfaction to you nor Thomas now. If he dies, the state will send his body and I home free.