This letter was written by John L. Phifer (1842-1880), who commenced his military service on June 7, 1861, hailing from Cabarrus County, North Carolina, as an 18-year-old private in Company A of the 20th North Carolina Infantry. He had a brief tenure with the Radecliff Battery before attaining the rank of ordnance sergeant in the 20th N.C. in March 1862. By 1865, he held the position of Brigade Ordnance Officer in Johnston’s Brigade, Early’s Division, and had recently arrived or was shortly expected at Camp Pegram. John was the offspring of Caleb Phifer (1810-1879) and Mary Adeline Ramseur (1817-1881) from Concord, Cabarrus County, North Carolina. At the onset of the Civil War, he was employed as a clerk.

This letter is preserved within the Phifer Family Papers, 1859; 1862-1864 at the University of North Carolina, where it has been digitized, though transcription and online posting have yet to occur. The letter’s images were sent to me for transcription by Matt Edwards, who posited that the letter was authored by Capt. George L. Phifer of the 49th North Carolina Infantry. However, I am firmly convinced that the signature clearly reads “J. L. Phifer” rather than “G. L. Phifer.” It is also significant to note that the letter was directed to John’s cousin and has remained with George’s family correspondence within the aforementioned collection.

The letter underscores John’s unwavering dedication to the Confederate cause, while also presenting the unexpected outcomes of a query directed at the soldiers within his Brigade, inquiring, “Should negroes be enlisted in the ranks of the Confederate army?”

Transcription

Camp near Petersburg, Virginia

February 22, 1865

Dear Cousin,

Your most welcome communication of February 9th was received and perused with much pleasure. I never for one moment thought it was from you. I had ceased to look for a reply and was regretting that I had written to you, but I am repaid for writing; but I hope you will be more prompt in future. When I looked at the direction, I thought it was from brother Charlie who writes an elegant hand. But I was most agreeably surprised to learn my mistake in glancing at the heading as you have brought to mind the “deer hunt in the mountains.” Permit me to explain what I meant. I spoke to Cousin Anna in a playful manner and said that she was deer enough for me, not meaning or intending that anyone else should think I meant dear for such was not my intention. I meant just what I said—that Counsin Anna was gay and happy, pleasant and very agreeable, full of life and fun, with whom I could enjoy myself and feel as though I was talking to a friend and nothing more. And I am sorry—very sorry—that you should have been so “exasperated” when I was talking for amusement only. I hope Cousin Anna did not construe my words as you did? Was she as much exasperated as you were? If she was, I did not perceive it. Do you think I would make so public an avowal of my love for a lady? If you do, you. know very little of my disposition. I am rather modest and retiring in love affairs. I would almost bet my life that Cousin Anna did not construe my words as you did. I think she is far seeing for that and a little too old to think so. Now, I do insist upon your telling me whether she was exasperated or not? My curiosity is much excited to know and perhaps that will explain some of her conduct towards me which I have never been able to understand.

Permit me to inform you that you are slightly mistaken when you imagine Miss M. Morehead is a particular friend of mine. Did I not tell you last spring about the manner she treated me when at Cousin Sarah Morehead’s. I advance half across the room to shake hands with her, [but] as she showed no signs of recognition, I retreated (in good order) to my seat, I was pretty much demoralized but stood my ground and held my position. Your delicate sense of politeness and good breeding will sustain me in thinking she intended it as she never apologized for it afterwards. I do not know anyone with the “initials W. H. M.” I will find out for you and let you know in my next.

I don’t think our sweet little Cousin Esther will ever make a match with Capt. N. P. Foard. I think if all her relations would let her alone, it might be a match, but there is Bob Fulenwider, Jimmy Gibson, Charlie Phifer, and many other of her cousins who don’t fancy it and are always making fun of him, calling him N. Post Foard and many other nick names. He was called Post at school for being so extremely dull. I am under many obligations to you for giving. or desiring to give me Miss Daisy Gutler for a “sweet heart,” but can’t promise to make any advance towards storming the fair one until the war is over. If she should require much daring and boldness of heart to capture, I must wait until the war ends so that my country does not need my whole time and attention. Perhaps she would not like the disposition you have made of her? Did you get acquainted with Miss Hattie Gilmer of Greensboro? I have had some gay times with her. I came very near falling in love with her; she has grey eyes and I don’t fancy them.

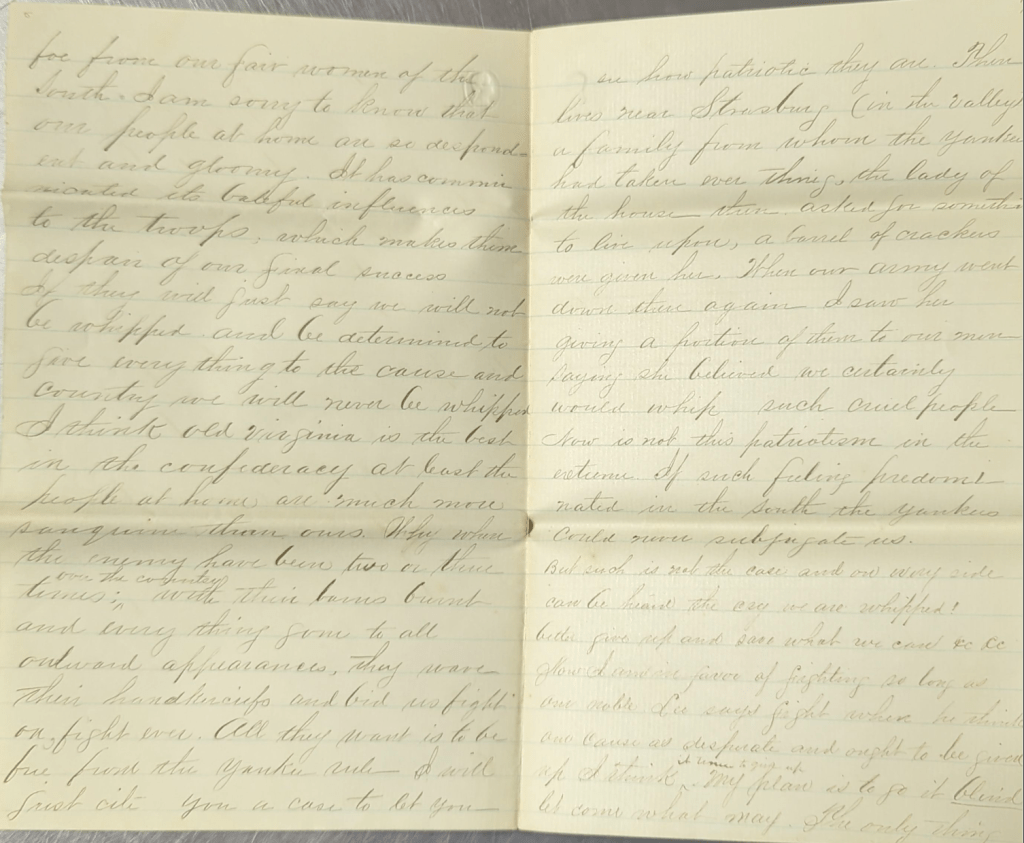

You speak of your ideas being frozen up on account of the cold weather. About that time our brave soldiers were out in the open air without any shelter, fighting and building fortifications to drive back the hated foe. I am much surprised at the ladies showing any fondness for the young men who remain at home, when our glorious country needs their strong arms to defend our homes and firesides, to drive back the Yankees and protect all we hold dear, to keep back the insolent foe from our fair women of the South. I am sorry to know that our people at home are so despondent and gloomy. It has communicated its baleful influences to the troops, which makes them despair of our final success. If they would just say we will not be whipped and be determined to give everything to the cause and country, we will never be whipped.

I think Old Virginia is the best in the Confederacy—at least the people at home are much more sanguine than ours. Why when the enemy have been two or three times over the country with their barns burnt and everything gone to all outward appearances, they wave their handkerchiefs and bid us fight on, fight ever. All they want is to be free from the Yankee rule. I will first cite you a case to let you see how patriotic they are. There lives near Strasburg (in the Valley) a family from whom the Yankees had taken everything. The lady of the house then asked for something to live upon. A barrel of crackers were given her. When our army went down there again, I saw her giving a portion of them to our men saying she believed we certainly would whip such cruel people. Now is not this patriotism in the extreme? If such feeling predominated in the South, the Yankees could never subjugate us.

But such is not the case and on every side can be heard the cry, “We are whipped—better give up and save what we can, &c. &c.” Now I am in favor of fighting so long as our noble Lee says fight. When he thinks our cause as desperate and ought to be given up, I think it time to give up. My plan is to go it blind, let come what may. The only thing that gives me much trouble is the old people and the lovely and devoted ladies of the South, also the helpless children. If these could take care of themselves, I have no fear for myself. As I am uncertain how this war might end. I am rather inclined to be indifferent to seeking one whom I would like better than myself and for whom I would feel more sensibly any injury done to her than to myself. So if you will select me a nice, pretty “sweetheart” from among your many friends who will. be of the same opinion as I have expressed (that is, wait till. the war is over), I will accept your choice. I might tell you of a certain young lady for whom I have the greatest admiration and I believe most of my friends desire me to propose, but as I have said, the war is one objection and I am so very modest that I don’t feel like making the attempt and to be rejected would almost kill me—not quite—so don’t.

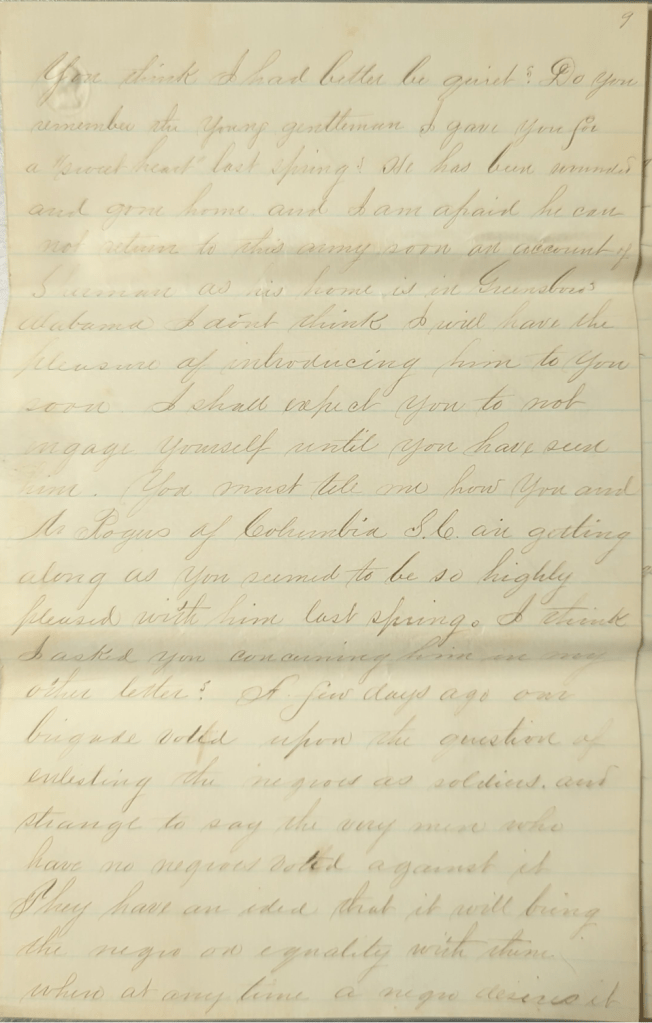

You think I had better be quiet? Do you remember the young gentleman I gave you for a “sweetheart” last spring? He has been wounded and gone home and I am afraid he cannot return to the army soon on account of Sherman as his home is in Greensboro, Alabama. I don’t think I will have the pleasure of introducing him to you soon. I shall expect you to not engage yourself until you have seen him. You must tell me how you and Mr. Rogers of Columbia, S. C. are getting along as you seemed to be so highly pleased with him last spring. I think I asked you concerning him in my other letter?

A few days ago our Brigade voted upon the question of enlisting the negroes as soldiers and strange to say the very men who have no negroes voted against it. They have an idea that it will bring the negro on equality with them when at any time a negro desires it, he can sit down and chat with these men as though he were an equal. The brigade voted for the measure by a slight majority. The Georgia troops voted for it almost unanimously and I understand troops from the Gulf States were in favor of bringing the negroes in as soldiers. Gen. Lee is of the opinion that we can make good soldiers of them—at least as good as the Yankee negro troops. Can you tell me any objection to making them fight? Just so we can gain our independence, I care not whether it be done by the aid of negroes or not.

May I not look for an early reply to this letter? Also a long letter of about three sheets or more and you must not think for a moment that I consider your letter as being. dull. If you keep saying yours are dull, I shall consider my own as being extremely uninteresting.

As I thought I could close my letter on half sheet, I began on one but find I cannot finish without crossing the writing. A few nights ago I had almost everything I had stolen from me by an extremely bold rogue. My hat and haversack were taken about two inches from my head. Mother had sent me a considerable amount of provision, such as sorghum, peas, butter, &c. All were taken, not leaving me anything good. I feel the loss very much as we enjoy things sent from home very much. I believe the rogue would have taken my pants from under my head so soundly do I sleep.

I think Cousin Lou Wilson stays at your home. If she does, please give her my love. She and I used to be old correspondents and were until she was married to Major Wilson. Also give my love to your Mother and Father and your little sister Sallie whom I remember as a beautiful little child when I was at your home. How is your brother Phife and is he with the western army or near Winnsboro, South Carolina?

Now if you don’t write soon and a long letter, I will be much disappointed. Can you. tell me of some pretty and sweet songs and the latest music published in Dixie as I promised to select some for a lady friend of mine and I am afraid to rely on my own judgement. I know you will be as tired of reading this as I am of writing for you know it takes some time to write so long a letter. If it was my dear little sweetheart I was writing to, I would not stop short of four sheets or more, but as you are only one of my many dear cousins, I will stop. I am afraid you will go to sleep ere you. finish. With much love, goodbye and keep in good heart as I am, Your affectionate Cousin, –J. L. Phifer

P. S. I heard that [George Washington] Kirk, the renegade, had made a raid near your town. Is it true?