The following letter is a rare. It was written by Joseph Scott of Princeton, New Jersey—a 19 year-old free Black man who served in Co. D, 6th United States Colored Troops (USCT). His muster roll records inform us that he was 18 when he enlisted on 12 August 1863 at Philadelphia. He was describes as standing 5 feet 6 inches tall, brown eyes, dark hair and light complexion. It further informs us that he was born in Monmouth, New Jersey and was employed as a laborer. Census records reveal that Joseph was likely the son of Charles W. Scott (1820-1904) and Martha L. Byles (1820-1859). Charles was a mulatto who grew up in Upper Freehold, Monmouth county, and in the 1860 US Census he was enumerated near Allentown and employed as a 45 year-old butcher.

Joe entered the service as a private but he was promoted to corporal at the camp near Yorktown on 24 October 1863. Muster records also inform us that though Joe survived the war, he did not survive the service. He died on 26 September 1865 at Hicks U.S. General Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland of phithisis pulmonalis (tuberculosis). He was admitted on 24 September and died two days later. He was buried in Laurel Cemetery, Grave No. 226. 1

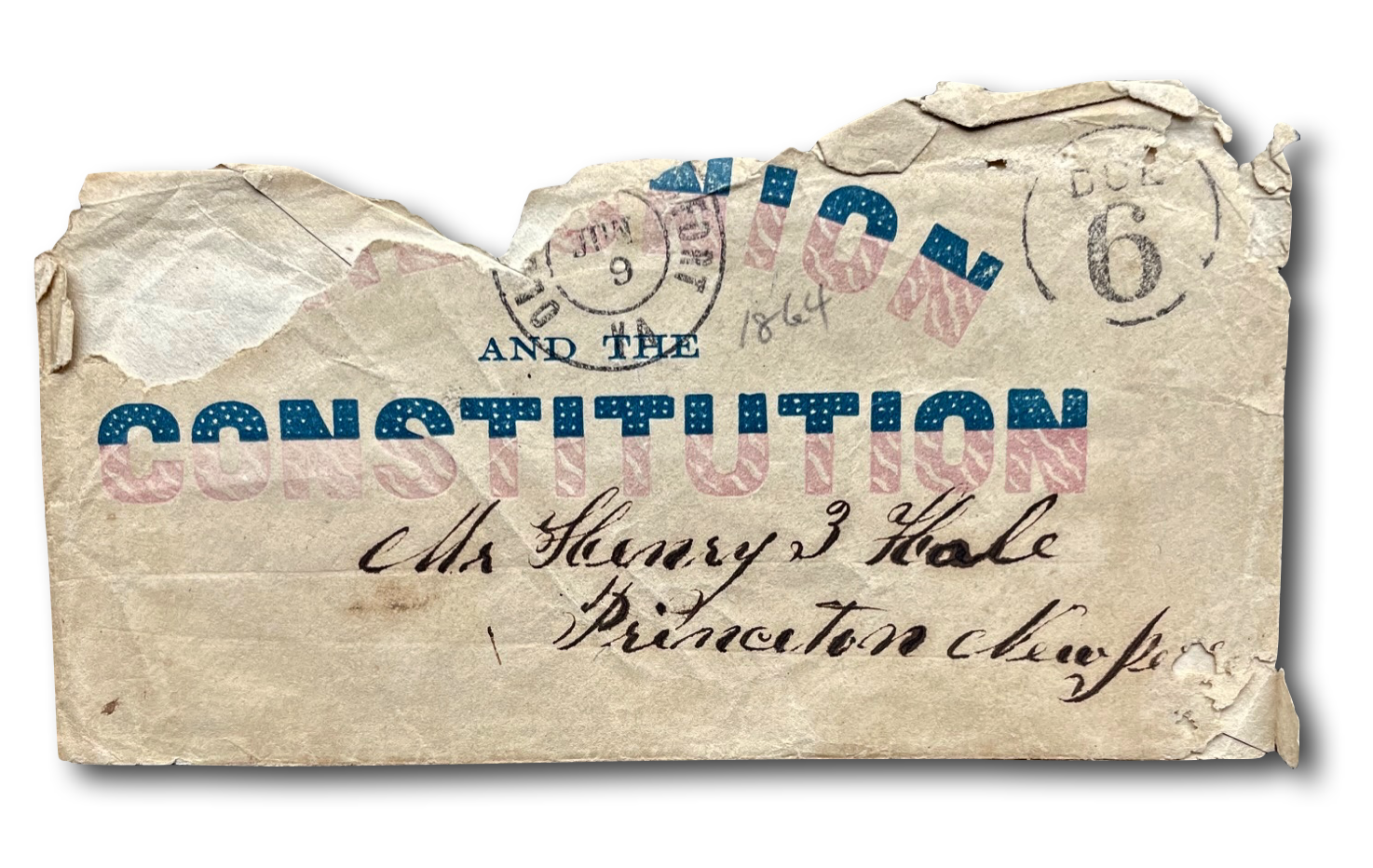

The letter was addressed to Henry E. Hale who I assume was Henry Ewing Hale (1840-1925), a young white man and an 1860 graduate of Princeton University. Why they would be correspondents, I can only conjecture though Hale may have maintained such communication in his capacity as secretary of the Princeton Standard and Trenton newspapers while he attended graduate school.

The following excerpts pertaining to the 6th USCT were lifted from Military Images Digital Magazine on June 2015, written by Candice Zollars:

“On Oct. 14, 1863, the 6th left Philadelphia for the Virginia coast and Fortress Monroe, where the regiment joined Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James. As the soldiers marched through the streets, one Philadelphia reporter stated, “They made a brilliant appearance.” The men and officers occupied the majority of their time on mundane tasks—performing fatigue and picket duty, guarding prisoners, tending horses, distributing rations and caring for the wounded. Nevertheless, one officer wrote with evident pride to a Philadelphia newspaper on Feb. 18, 1864, “Their clothes are dirtier and rustier, but the men stand more erect, and my regimental line, now, is almost motionless.”

“The regiment received its baptism under fire on June 15 when it participated in an assault on a section of Confederate earthworks near Petersburg. Capt. Harvey J. Covell of Company B described the fighting in a letter to his wife as “about as hot a place as I ever saw.” As Covell hid “behind a little tree a shell struck within a few feet and … exploded among us.” The men found that they could dodge the artillery fire “if it struck the ground before it reached us as it usually would.” One shell “exploded a few feet in front of me the balls and fragments flying all around me,” he wrote. Covell emerged unscathed from the engagement.

“On Sept. 29, the 6th participated in an assault on the Richmond defenses at New Market Heights. The regiment suffered heavy casualties—209 of 367 engaged, or a loss of 57 percent. Among the dead was Pvt. Hamilton, who had drawn a razor on Capt. McMurray in camp a few months earlier. The wounded included Capt. Robert B. Beath, who endured the amputation of his right leg. At one point during the fight, McMurray found Adjutant Charles V. York lying by a path in excruciating pain from a wound. McMurray took note of York’s position and continued on with his command.

“Maj. Gen. Butler praised the conduct of those in his command who fought at New Market Heights: “In the charge on the enemy’s works,” Butler noted, “better men were never better led, better officers never led better men. With hardly an exception, officers of colored troops have justified the care with which they have been selected.” He added, mindful of Northern critics of black soldiers in blue, “A few more such charges, and to command colored troops will be the post of honor in the American armies. The colored soldiers, by coolness, steadiness, and determined courage and dash, have silenced every cavil of the doubters of their soldierly capacity, and drawn tokens of admiration from their enemies.”

Note: This letter is from the private collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

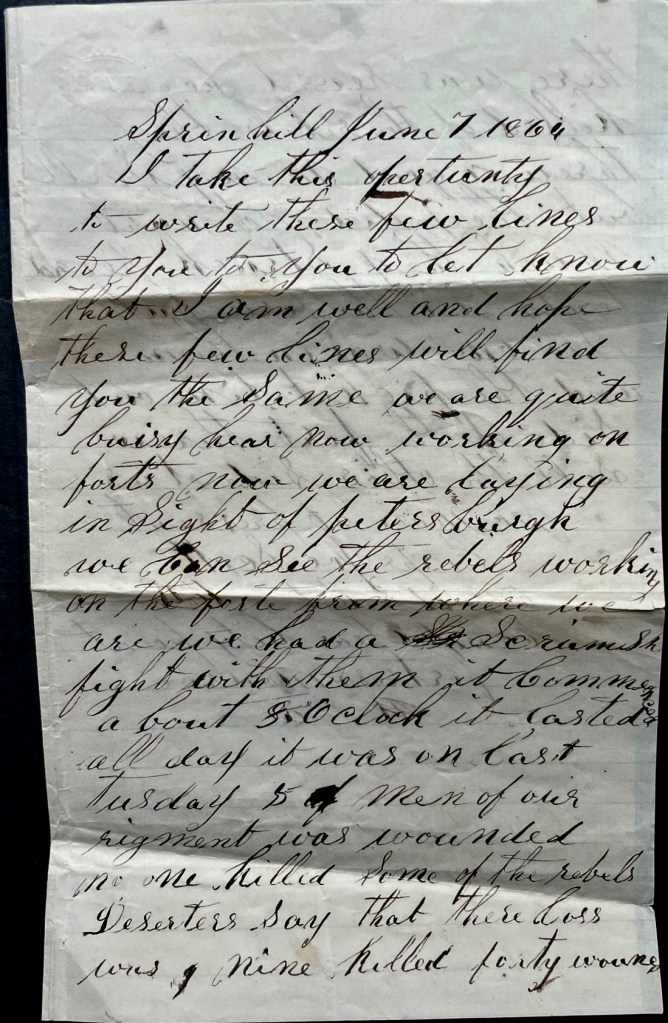

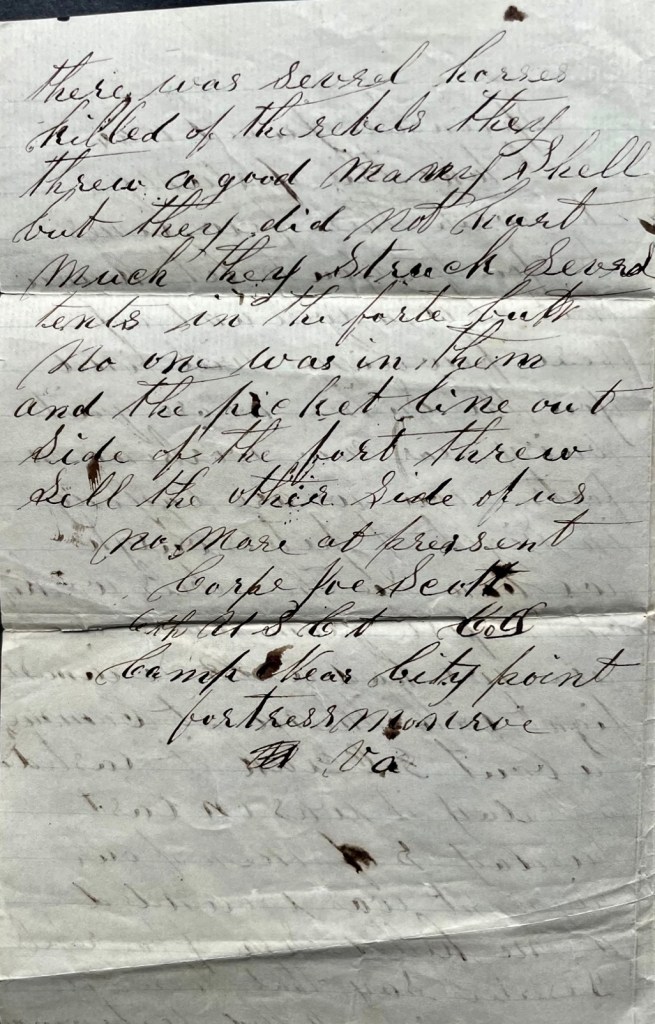

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Spring Hill [on Appomattox River 5 miles from Petersburg]

June 7, 1864

I take this opportunity to write these few lines to you to let you know that I am well and hope these few lines will find you the same. We are quite busy here now working on forts now. 2 We are laying in sight of Petersburg. We can see the rebels working on the fort from where we are.

We had a skirmish fight with them. It commenced about 8 o’clock. It lasted all day. It was on last Tuesday. Five men of our regiment was wounded. No one killed. Some of the rebel deserters say that their loss was nine killed, forty wounded. There was several horses killed of the rebels. They threw a good many shells but they did not hurt much. They struck several tents in the fort but no one was in them and the picket line outside of the fort threw shells the other side of us.

No more at present. Corp. Joe Scott, 6th USCT, Co. D, Camp near City Point, Fortress Monroe, Va.

1 “Laurel Cemetery was incorporated in 1852 as Baltimore’s first nondenominational cemetery for African Americans. The location chosen was Belle Air Avenue (now Belair Road), on a hill long used as a burial ground for free and enslaved servants of local landowners. Laurel quickly became a popular place of burial for people across Black Baltimore’s socioeconomic spectrum, including the graves of 230 Black Civil War veterans, members of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.). After its creation, Laurel Cemetery was known as one of the most beautiful and prominent African American cemeteries in the city…. In the late 1800’s, annual parades and Memorial Day gatherings to honor and decorate the graves of the Black Civil War veterans occurred regularly at Laurel Cemetery, which was also the resting place of many prominent members of Baltimore’s African American population. Historical records show that in 1894, Frederick Douglass traveled to Laurel Cemetery to speak on the occasion of the unveiling of a monument honoring Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne, who served as the sixth Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopalian (A.M.E.) church, and was a founder and former president of Wilberforce University….The decline of Laurel Cemetery started in the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1911, the remains of the Civil War veterans were removed and reinterred at Loudon Park National Cemetery to accommodate the expansion of Belair Road.”

2 The fortification Joseph refers to came to be known as Redoubt Converse, intended for the protection of a pontoon bridge at that location.