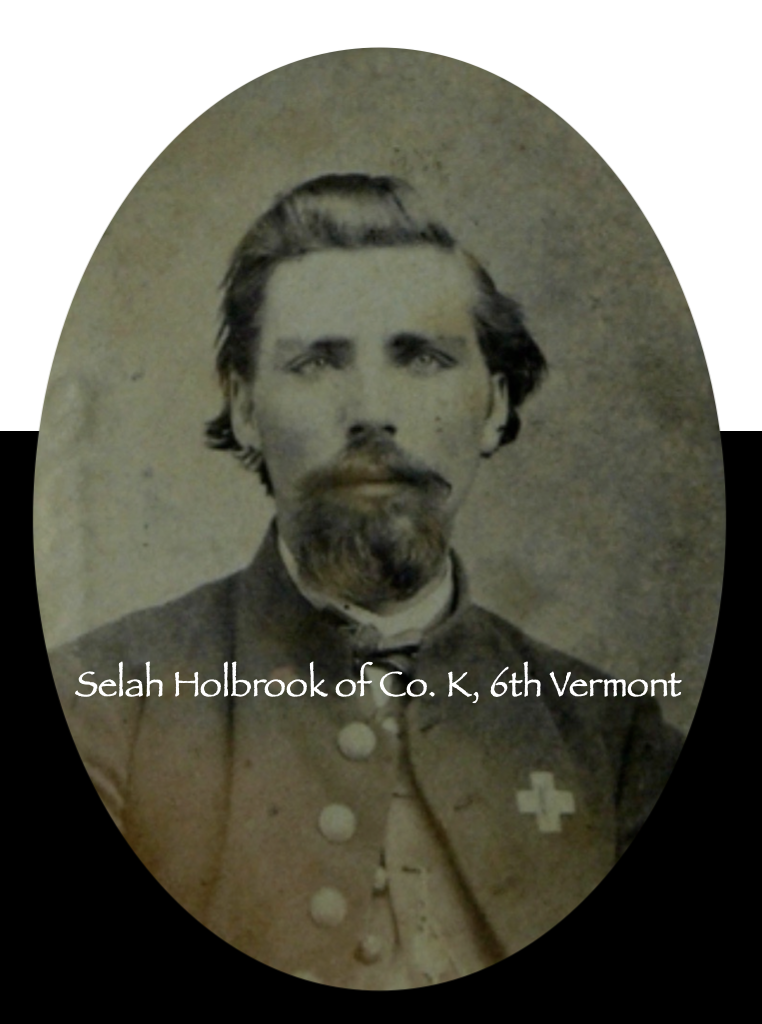

The following letters were written by Elijah J. Williams (1822-1864), the son of Thomas Williams (1776-1856) and Talitha Rust (1780-1856) of Williamstown, Orange county, Vermont.

He moved to Barton in 1859 following the death of his eleven-year-old daughter in Williamstown, Vermont. He found employment as a painter in a chair factory on Water Street. He and his wife Susan Deborah (Stimson) Williams (1828-1901) lived in a tenement house on High Street with their two children Elthia and Melbourne. In mid-August 1862, forty-year-old Elijah Williams enlisted into the army and became a member of Co. D, 6th Vermont Regiment. His enrollment records inform us that he had stood six feet tall and had dark hair and black eyes. Muster rolls reveal he was always present for duty and for his reliability, he was promoted to corporal in February 1864. Sadly, he was wounded in the thigh on May 5, 1864 as they defended the Orange Plank Road in the first day’s fighting of the Battle of the Wilderness. In his official report, Col. Lewis Grant who led the Vermont Brigade wrote of the day’s fighting: “Darkness came on and the firing ceased. One engaged in that terrible conflict may well pause to reflect upon the horrors of that night. Officers and men lay down to rest amid the groans of the wounded and dying and the dead bodies of their comrades as they were brought to the rear. One thousand brave officers and men of the Vermont Brigade fell on that bloody field.”

Elijah’s wound was so severe that he died four days later in a Fredericksburg hospital. He was buried somewhere in Virginia but a cenotaph memorializes him in his hometown of Williamstown, Vermont. His wife Susan eventually remarried in Barton in the spring of 1870 to Abner W. Lyman (1830-1916). She died in Haverhill, New Hampshire in 1901. [Source: Dan Taylor]

See also: “Maelstrom in the Wilderness: The deadliest day in Vermont history,” by John Gibson. Military Images Magazine, March 3, 2018.

These letters are from the personal collection of Les Kaufman who graciously offered them for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

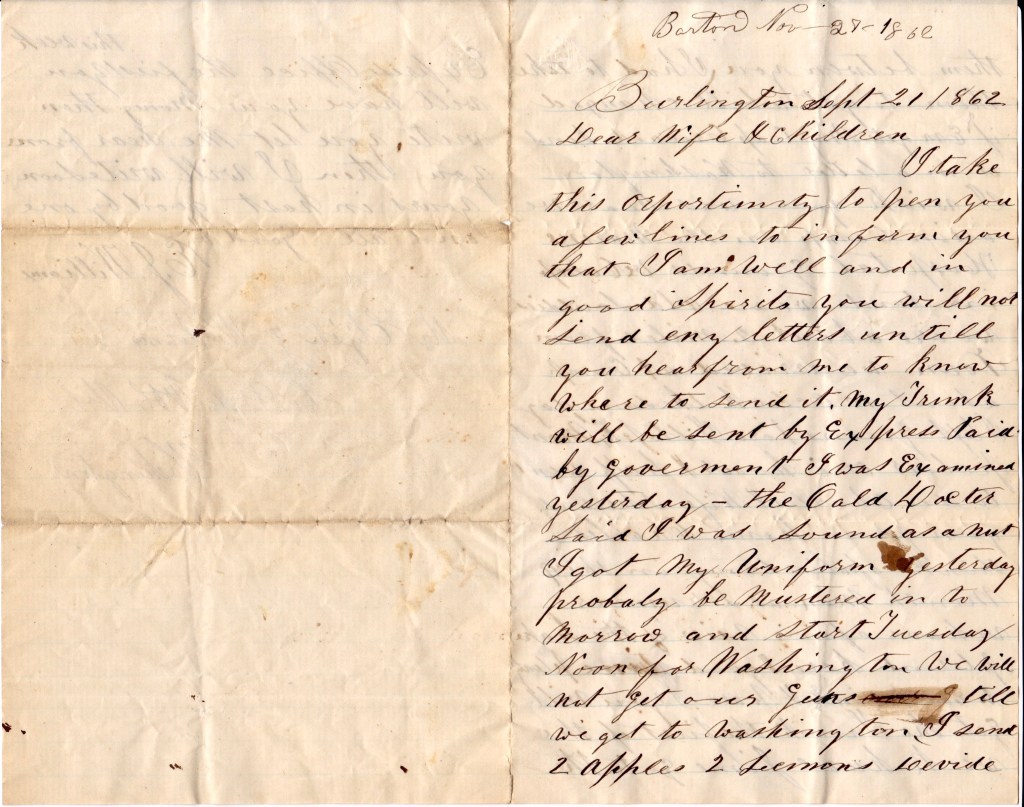

Letter 1

Burlington [Vermont]

September 21, 1862

My dear wife & children,

I take this opportunity to pen you a few lines to inform you that I am well and in good spirits. You will not send any letters until you hear from me to know where to send it. My trunk will be sent by express paid by government. I was examined yesterday. The Old Doctor said I was sound as a nut. I got my uniform yesterday. Probably be mustered in tomorrow and start Tuesday noon for Washington. We will not get our guns till we get to Washington.

I send two apples, two lemons. Divide them between you. I had to take them to get a bill changed. If Em gets my cap crocheted, send it in a letter to Washington. I wish you was hear. We are in camp on the Marine Hospital grounds. We camp in tents. We are old soldiers. We are about two miles from town. We arrived at camp about ten o’clock the same day I left Greensboro. I stopped at Montpelier one hour and a half. Went to see Charles & wife. She was gone from home. Charles thinks of enlisting in the nine months men as drummer. We have a fine view of the lake. Pleasant here & good times. Plenty to eat, to drink, & wear. You will get the trunk the first of the week. Have Jim go to the Express Office the first of this week. You will have your money then.

Write. You let me hear from you. Then I will write soon. Yours in haste. Goodbye one and all. Goodbye. — E. J. Williams

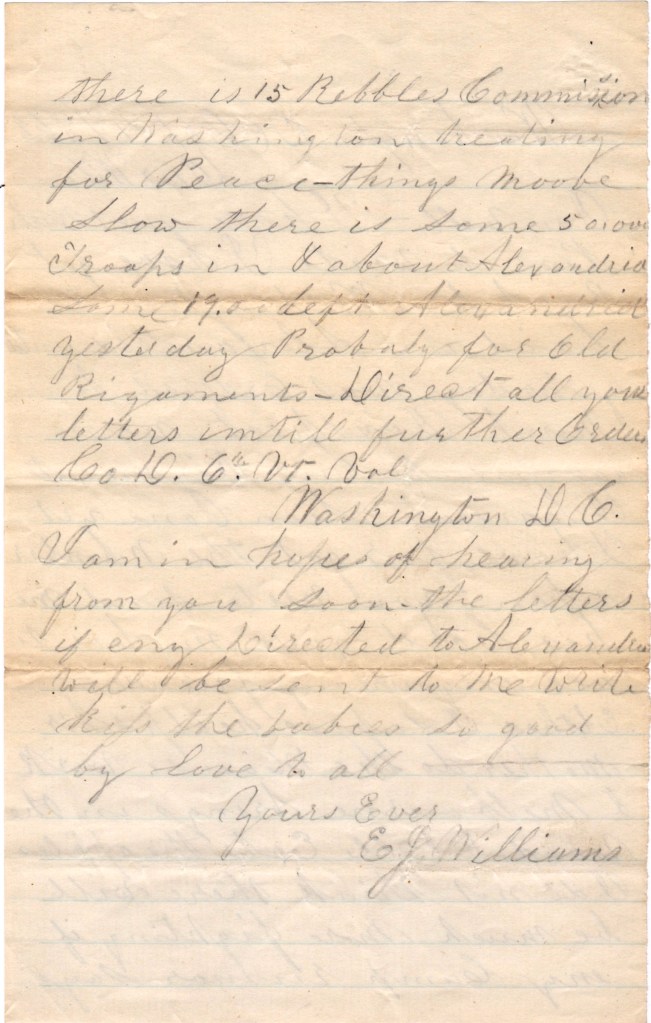

Letter 2

Washington D. C.

October 4, 1862

Dear wife,

I am well. I have not much news to write. I have got back to Washington. We laid in Alexandria until yesterday. Was ordered to march. I expect we are agoin’ to our regiment. I haven’t seen Cone yet. I have forgot the number. When you write, send me his cord. Give my love to all enquiring friends. Elthea, I suppose, helps her mother do the housework. I [suppose] Melbourne brings in the wood & Elle eats the apples.

I do not think there will be much more fighting if any. Camp rumor says there is 15 Rebel Commissioners in Washington treating for peace. Things move slow. There is some 50,000 troops in & about Alexandria yesterday—probably for old regiments.

Direct all your letters until further orders to Co. D, 6th Vermont Vols., Washington D. C.

I am in hopes of hearing from you soon. The letters, in any, directed to Alexandria will be sent to me. Write. Kiss the babies. So goodbye. Love to all. Yours as ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 3

Camp near Hagerstown, Maryland

October 11, 1862

Dear wife & children,

I take my pen in hand to write you a few lines. I left Greensboro September 19th for Burlington eat supper 10 p.m. Camped on the ground in the Marine Hospital yard some two miles from Burlington Village in sight of Fort Kent York State, Shelburne Bay, Vermont.

20th Examined & uniformed.

21st Sunday.

22nd Mustered into service of the United States & signed the pay roll. Mustered in by Major Austin.

23rd Received Pat State, pay $9.80, Bounty $25, United States $13, Premium $4, making in all $51.80. On guard first time 4 hours.

September 24th. Started for seat of war. Left Burlington about 10 a.m. Stopped at Vergens, Middlebury. Brandon & Rutland, Vermont. Arrived at Troy, New York, same day at half past 5 p.m. The depot at Troy was burnt last summer. It burnt over 70 acres. We were marched to the Female Seminary grounds to wait for the boat to take us to New York City. The proprietor of the Seminary gave us a treat in peaches, crackers, and cheese. Carried on board the boat Francis Cadd. We went on board about sunset. Set sail about 9 p.m. got on a sand bar. Laid on about two hours. Arrived at New York City on the 25th, 11 o’clock a.m. Marched to the City Park, stopped about two hours, marched through Broadway some two miles. Turned on to another street to the wharf. Went on board the Richard Stockton for Amboy, New Jersey. Went on board the ferry boat. Arrived at Philadelphia 12 o’clock midnight. Marched to the Soldiers’ Home and had a splendid supper got up by the ladies (God bless them). Then marched to the Baltimore Depot at half past 2. Camped on the Depot floor. Started from Philadelphia in the cars at half past 5 a.m.

September 26th, arrived at Baltimore at dusk. Took supper. Slept in the depot.

September 27th, took breakfast & started for Washington. Arrived at Washington 6 o’clock p.m. when we went to supper at Washington at the Soldiers’ Retreat. It was enough to sicken a hog. Fare consisted of one slice of bread [and] one slice of pork alive with maggots. It had been put on until the maggots carried it off. Coffee in pails looks like dish water—hot and no dippers to dip it out. There was some 300 soldiers standing around the tables and not over two dozen dippers for the whole to drink out of.

When we arrived at Camden we went on board the ferry boat cars and engines 16 cars, 8 on a side. Engine in the center with about 500 persons on board crossed from Camden to Havre de Grace. Thence to Baltimore. It is a fine country from Burlington, Vermont, to Pennsylvania through the whole state up to Delaware line. Some fine farms in Delaware but you can tell the difference in the Free States. The farms are well cultivated, buildings looks neat & tidy, painted up in good shape. Front yards. There were some fine farms in New Jersey. The people were very enthusiastic all along from Burlington, Vermont, to Delaware line.

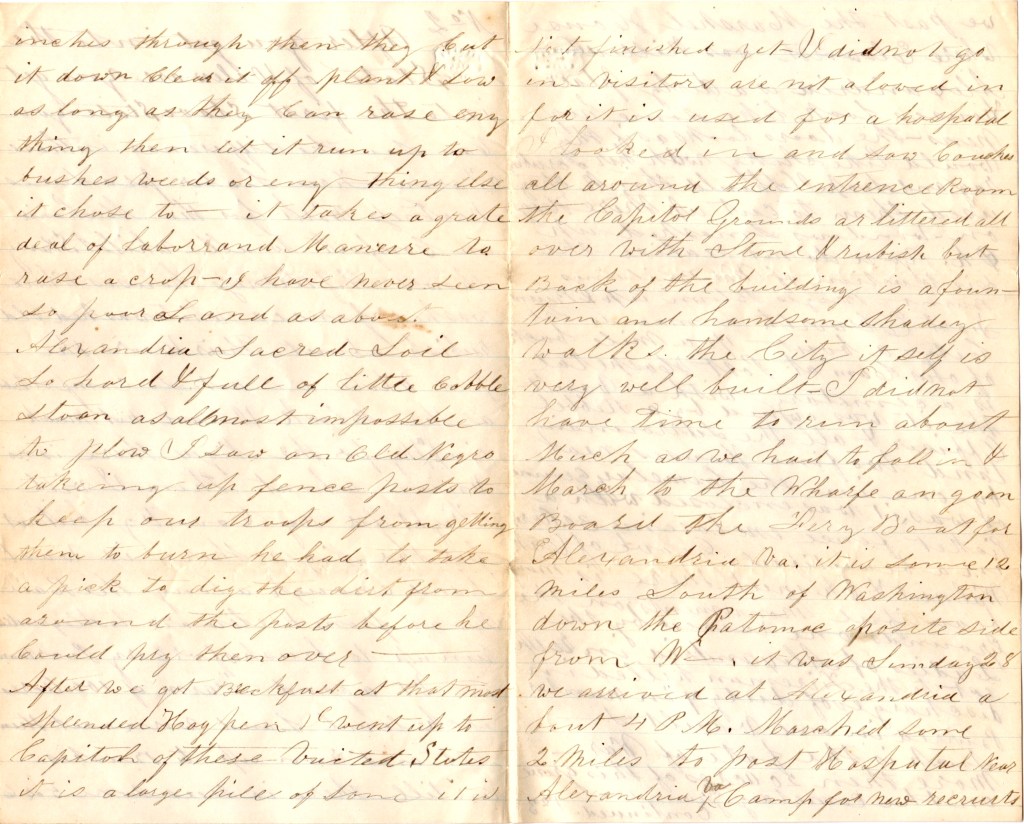

After you get into the State of Delaware, you get into the first slave state. You can see the difference in their farms. Free labor produces neatness, work for the mechanic, and comfort to all, whilst slavery shows shiftlessness, houses white-washed, fences whitewashed, old rubbish about their doors. The poor White are not so comfortable as the Black. I have not much sympathy for the niggers. There is no Union about them. I will fight for my country but not for the nigger. There is waste land enough along the railroad from Delaware to Alexandria run up to brushes for every poor man in Vermont a good farm of 100 acres each, level land worn out, then left and run up to bushes until there is trees some 5 or 6 inches through. Then they cut it down, clear it off, plant & sow as long as they can raise anything. Then let it run up to bushes, weeds, or anything else it chose to. It takes a great deal of labor and manure to raise a crop. I have never seen so poor land as about Alexandria—Sacred Soil—so hard and full of little cobble stones as almost impossible to plow. I saw an old negro taking up fence posts to keep our troops from getting them to burn. He had to take a pick to dig the dirt from around the posts before he could pry them over.

After we got breakfast at that most splendid hog pen, I went up to the Capitol of these United States. It is a large pile of stone. It is not finished yet. I did not go in. Visitors are not allowed in for it is used for a hospital. I looked in and saw couches all around the entrance room. The Capitol grounds are littered all over with stone & rubbish but back of the building is a fountain and handsome shady walks. The City itself is very well built. I did not have time to run about much as we had to fall in & march to the wharf and go on board the ferry boat for Alexandria, Virginia. It is some 12 miles south of Washington down the Potomac, opposite side from Washington. It was Sunday 28th. We arrived at Alexandria about 4 p.m., marched some two miles to Post Hospital near Alexandria, Virginia, camp for new recruits. We passed the Marshall House where Ellsworth was killed. Alexandria is a dirty place. Houses look like some hog pens. The doors look as if they would like Suky with her scrubbing rag and soap. I should think they used them to cut up their hogs on. Windows smashed up. Oh! you do not realize the distribution of war buildings burnt, bridges blown up & burnt.

Fort Ellsworth commands the City. About half a mile back of our camp at Post Hospital is a cemetery with a vault. It was owned by a Rebel officer & all the surrounding land. Two fine houses nearby, one in the cemetery ground—or was, it was enclosed with a picket fence enclosing 30 acres in a beautiful grove of oak, walnut, and chestnut. There is many beautiful monuments on the grounds, one raised by the ladies of Alexandria in respect to the firemen killed in discharge of duty, 7 in number, buried in one vault & such is the fate of war. More than 20 acres of this grove on the cemetery ground. The fence most all torn down and burnt. Tombs opened in search of arms. Horses tied to grave lot fences. Hundreds of acres of lands run to waste. Families forsaking home and their all to tender mercies of a ruthless foe.

The Rebel officer who owns the grounds I spoke about was killed and put in the vault. It is a tomb with a stone front on a side hill bricked up and arched over head. It will hold some 24 coffins set on iron bars. There was eight in the vault when I was there. This officer was put in an iron casket & placed in a wood box. The screws were all removed but one. This cover could be removed to enable you to turn a iron cover from a glass in the casket. I took a match and lit it and saw the corpse. The iron door was blown open in search of arms. They found some 15,000 stands of arms hid by the Rebels and the door has been open ever since. His widow has left and gone to Boston.

We left camp near Alexandria October 3rd, went on board a towboat, went to Washington to that beautiful Soldiers’ Retreat. Stayed all night. Next morning, October 4th, had a fight. One man stabbed another. He died next morning. The other court martialed & sentenced to be shot on the 5th at 3 p.m. After dinner we went on board the cars for our regiment’s 39 car loads. Rode all night. One man named Curtis got sleep in the top of the cars and rolled off and killed.

October 5, arrived at Frederick Junction. Crossed the Monocacy on a trestle bridge built where the Rebels blew up an iron bridge. Cost some 30,000. It is three miles from Frederick City. Here we arrived at the Rebel’s last battle ground—that is, on the 5 Day’s Fight. Towards night we arrived at Harpers Ferry where John Brown was taken. It was burnt by the Rebels about one year ago & held by our forces until given up by Col. Miles—that arch traitor. We went about 2 and a half miles from Harpers Ferry and camped at the foot of Maryland Heights. Stayed the 6th. I went onto the Heights and could see hundreds of miles each way all through the Shenandoah Valley where Banks retreated back and is now held by the Rebels. Col. Miles surrendered to the Rebels when he could have held it—so the inhabitants told me. He was shot by one of his own men as he was lowering the flag, not as the papers say by a piece of shell from the enemy. He sold the army 8 to 12,000 who could [have] held the place against 5 times that number.

McDowell is another traitor, so called. He is not in command now. General Sumner’s Corps occupies the heights in Virginia—some 60,000 men. I went on Maryland Heights with a Lieutenant of the 73rd New York. Saw five graves—South Carolinians. Three bodies were thrown over the rocks and burnt. The Lieutenant dug up from the bones one foot burnt off at the ankle bone. The flesh burnt off but left the cords so as to keep the bones together. He put it on a stick and brought it into camp.

October 7th. Last evening some 300 more men came in. This morning took up. the line of march. Marched some 15 miles. Encamped on a small creek some three miles north of Sharpsburg. We stopped at Sharpsburg some three hours. It showed the effects of shot & shell. One building, the whole front, was completely riddled with canister from a shell bursting in front of the house. The holes are about as big as 1 inch auger hole. Another had shell strike in the back side making a hole as large as 7 inch stove pipe & dropped in the room but did not burst. If it had, it would stove it to flitters. Another struck in the corner of the jet, stove up the jetting & brick on the gable end. Lots of others were more or less shattered. Two were burnt by the shells. Sharpsburg includes the battle ground of Antietam. All of those places mentioned includes the Great Battle of Antietam some six miles in length by two miles wide. We came by a schoolhouse. Well you take a skimmer, then think of one as large as the front of the house you live in. It was completely riddled. I could mention a thousand of similar ones but it would take a week.

We started on the 8th [and] marched about three miles to Franklin’s Headquarters. Stayed all night. Next day until 4 p.m., [then] took up the line of [march] to join our regiments which reached about 10 p.m

October 9th & camped on the ground. Next morning went to our several regiments into tents. Nothing worth mentioning on the 10th. We have had no rain since September 24th until last night, the 11th. We had an alarm. All the Brigade turned out but the 6th Regiment. It was on City Guard. We are encamped one mile from Hagerstown on the south side of the City. I have not been to the city. Am going this afternoon. The alarm I spoke of was a Rebel raid. They crossed at Dam No. 5, went into Pennsylvania in the outside of our lines to Chambersburg, destroyed some of our stores with the Depot, thence onto the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, thence through our lines to Nolan’s Ferry, back over the Potomac with but little loss. The circuit they took was about 112 miles. They took back from 8 to 1,000 horses taken from the farmers in Pennsylvania. The horses were loaded with shoes and clothing taken at Chambersburg 25 miles from Hagerstown. The 2nd and 5th Vermont Regiments are at Chambersburg. The 3rd & 4th [Vermont] have come back.

Give my love to Mr. Simonds & wife. Mr. Bennett & Family, Mr. Pond & wife, & all the rest. I have received one letter dated October 7th. Tell Em I have not had a chance to get my regimentals taken yet. Save your money as much as you can for I may not get paid for two months to come. I hope you will go to Williamstown. Then the allotment I will make to you. I wished I had made it to you, then you could get a [sewing] machine. Kiss the babies for me. I will write to the children next time. So goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 4

Camp near Williamsport, Maryland

October 31, 1862

My ever dear wife & children,

I received your letter & was glad to hear that you was all well. Tell Elle he may get all the apples he can eat if Mama has taken away his tity—naughty Ma Ma. Tell Elthea I am glad to hear of her good resolves. Hope by God’s blessing she will endeavor to help her little brother’s as well. Mother be kind one towards each other.

I am well. We have moved six miles from Hagerstown the 28th. I expect to move tomorrow—some says to Boonsville, some to Dam No. 4. All I know there is a large movement of troops.

You must give up your sewing machine until we are paid. We were mustered out two months today. Perhaps we shall not get our pay for two months to come. We are mustered every two months—pay day is once every two months. They have not paid the old soldiers for four months. They probably will be paid by the 15th November. If they don’t get but two months pay, we new recruits will have to wait until they get their last two months pay. When we are paid, probably you will be able to pay part. You said you could get some money. I presume Lewis might hire $50 of Hunt & pay him in the course of six months. See Lewis and find out his mind. It is my wish for you to have a machine. I will find out by Cone by the time I get answers from this. Put the cap in a large envelope. Send it along. Direct as heretofore. My love to all. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 5

Camp on the march in Virginia

November 5, 1862

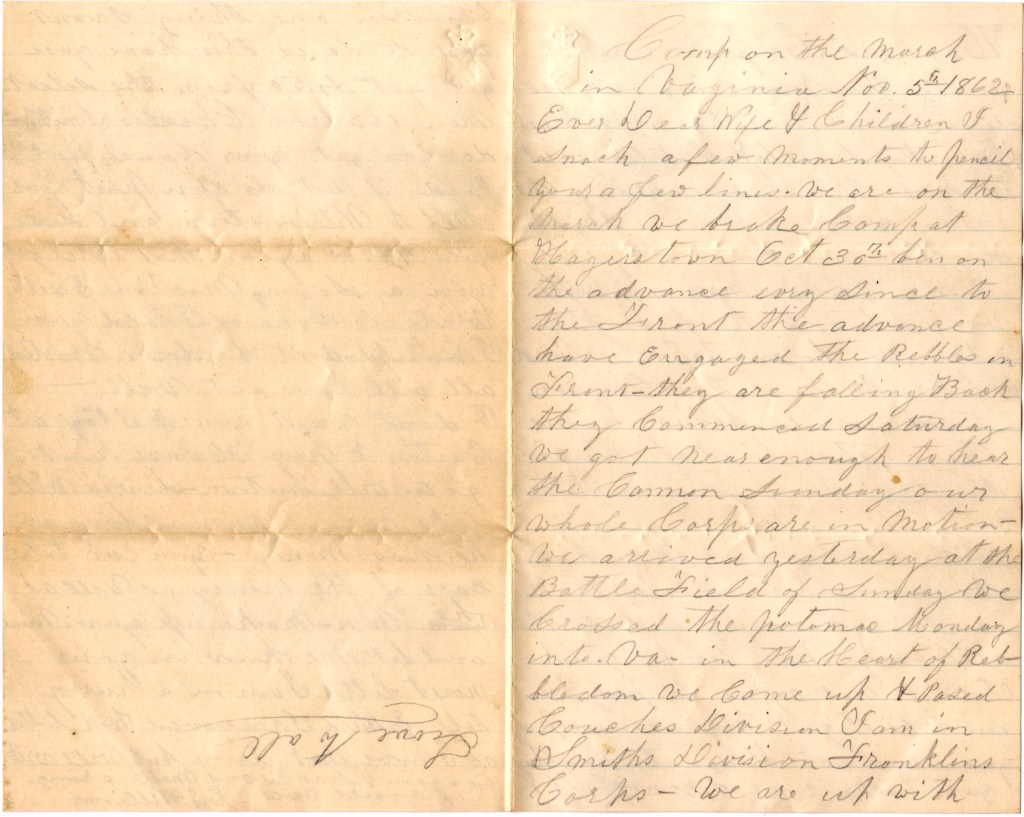

Ever dear wife & children.

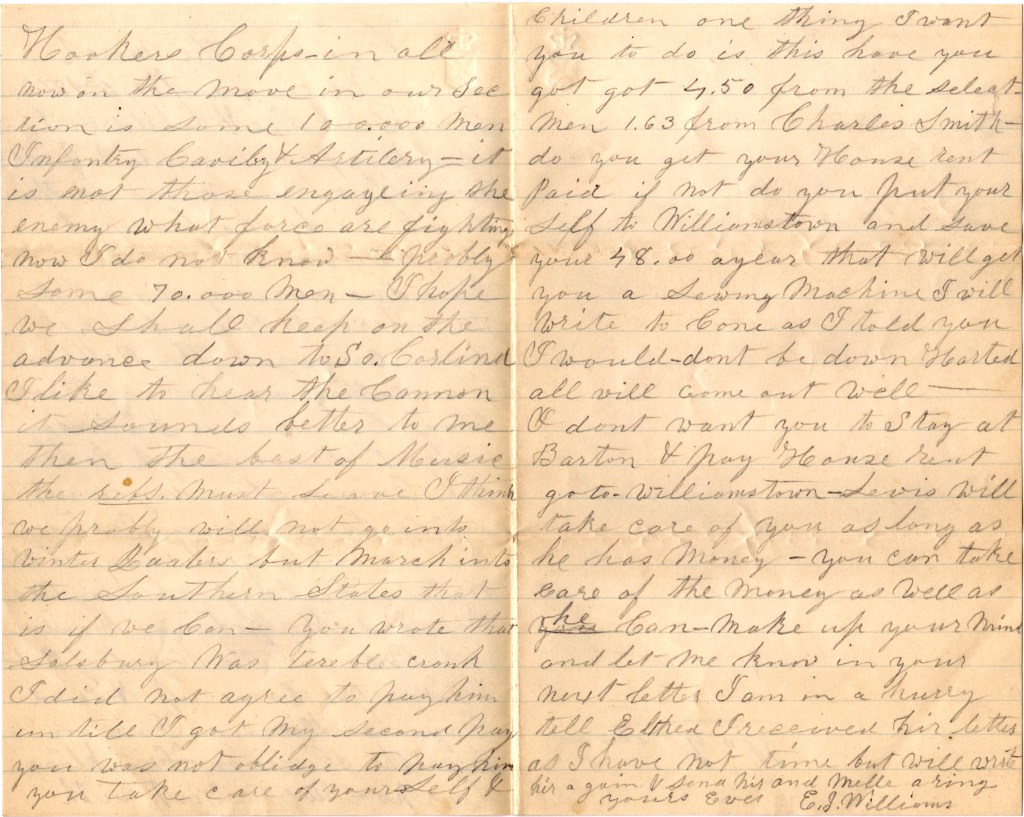

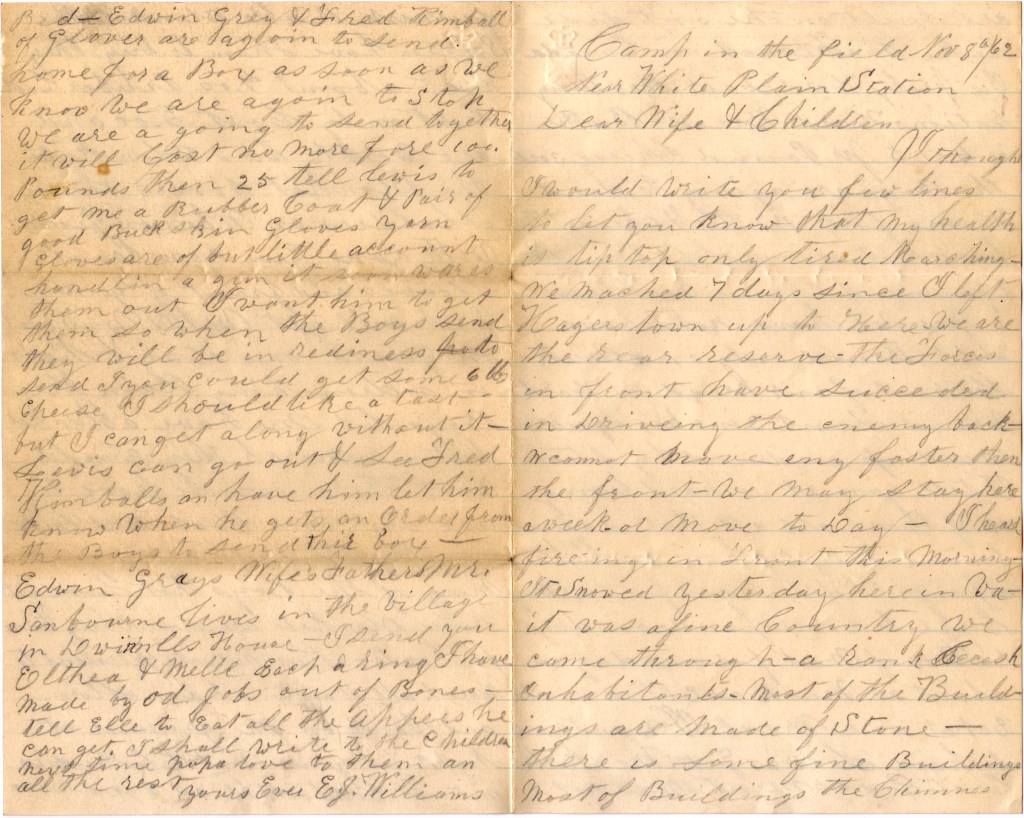

I sneak a few moments to pencil you a few lines. We are on the march. We broke camp at Hagerstown October 30th. Been on the advance ever since to the front. The advance have engaged the Rebels in front. They are falling back. They commenced Saturday. We got near enough to hear the cannon Sunday. Our whole Corps are in motion. We arrived yesterday at the battlefield of Sunday. We crossed the Potomac Monday into Virginia, in the heart of Rebeldom. We came up & passed Couch’s Division. I am in Smith’s Division, Franklin’s Corps. We are up with Hooker’s Corps. In all now on the move in our Section is some 100,000 men—infantry, cavalry, and artillery. It is not those engaging the enemy. What forces are fighting now, I do not know—probably some 70,000 men.

I hope we shall keep on the advance down to South Carolina. I like to hear the cannon. It sounds better to me than the best music. The rebs must leave, I think. We probably will not go into winter quarters but march into the Southern states—that is, if we can.

You wrote that Solsbury was [a] terrible crank. I did not agree to pay him until I got my second pay. You was not obliged to pay him. You take care of yourself & children. One thing I want you to do is this. Have you got 4.50 from the selectmen, 1.63 from Charles Smith? Do you get your house rent paid? If not, do you put yourself to Williamstown and save your $48 a year? That will get you a sewing machine. I will write to Cone as I told you I would. Don’t be down-hearted. All will come out well. I don’t want you to stay at Barton & pay house rent. Go to Williamstown. Lewis will take care of you as long as he has money. You can take care of the money as well as he can. Make up your mind and let me know in your next letter.

I am in a hurry. Tell Elthea I received her letter as I have not time but will write her again & send her and Melle a ring. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 6

Camp in the field near White Plain Station

November 8th 1862

Dear wife and children,

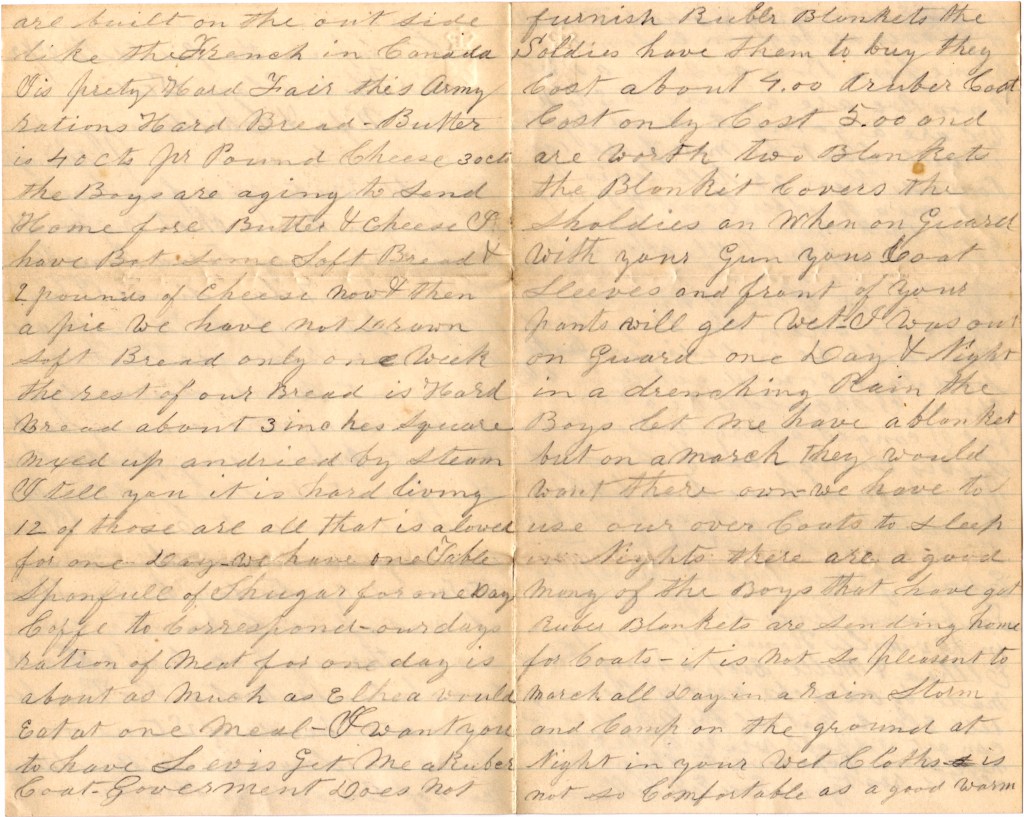

I thought I would write you a few lines to let you know that my health is tip top—only tired marching. We marched seven days since I left Hagerstown up to here. We are the rear reserve. The forces in front have succeeded in driving the enemy back. We cannot move any faster than the front. We may stay here a week or move today. I heard firing in front this morning. It snowed yesterday here in Virginia. It was a fine country we came through—a rank secesh inhabits. Most of the buildings are made of stone. There is some fine buildings. Most of the buildings, the chimneys are built on the outside like the French in Canada.

Tis pretty hard fare these army rations—hard bread. Butter is 40 cents per pound, cheese 30 cents. The Boys are a going to send home for butter and cheese. I have bought some soft bread & two pounds of cheese, now and then a pie. We have not known soft bread only one week. The rest of our bread is hard bread about 3 inches square, mixred up and dried by steam. I tell you, it is hard living. Twelve of those are all that is allowed for one day. We have one table spoonful of sugar for one day. Coffee to correspond. Our day’s ration of meat for one day is about as much as Elthea would eat at one meal.

I want you to have Lewis get me a rubber coat. The government does not furnish rubber blankets. The soldiers have to buy. They cost about $4. A rubber coat only cost $5 and are worth two blankets. The blanket [only] covers the shoulders and when on guard with your gun, your coat sleeves and front of your pants will get wet. I was out on guard one day and night in a drenching rain. The Boys let me have a blanket but on a march they would want their own. We have to use our overcoats to sleep in nights. There are a good many of the Boys that have got rubber blankets are sending home for coats. It is not so pleasant to march all day in a rainstorm and camp on the ground at night in your wet clothes is not so comfortable as a good warm bed.

Edwin Grey & Fred Kimball of Glover are a going to send home for a box as soon as we know we are a going to stop. We are a going to send together. It will cost no more for 100 pounds than 25. Tell Lewis to get me a rubber coat and pair of good buckskin gloves. Yarn gloves are of but little account handling a gun. It soon wears them out. I want him to get them so when the Boys send, they will be in readiness to send. If you could get some 6 lbs. cheese, I should like a taste, but I can get along without it. Lewis can go out and see Fred Kimball’s and have him let him know when he gets an order from the Boys to send their box. Edwin Gray’s wife’s father—Mr. Sanborne—lives in the village in Dwi__ll’s house. I send you, Elthea and Melle each a ring I have made by odd jobs out of bones. Tell Elle to eat all the apples he can get. I shall write to the children next time. Papa love to them and all the rest. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 7

Camp near Falmouth, Virginia

December 10th 1862

Dear wife and children,

I take this opportunity to let you know that I am well except a cough which troubles me nights.

I received on the 4th two letters—your last and the one you wrote to Hagerstown. We started on the advance in half an hour after getting it. Did not have time to write you before. We were paid off yesterday so there will be $11 in the Treasury on the allotment the first of January. There will be $22 if we are paid the way they pay us. We are mustered out every two months. Our pay is due every two months.

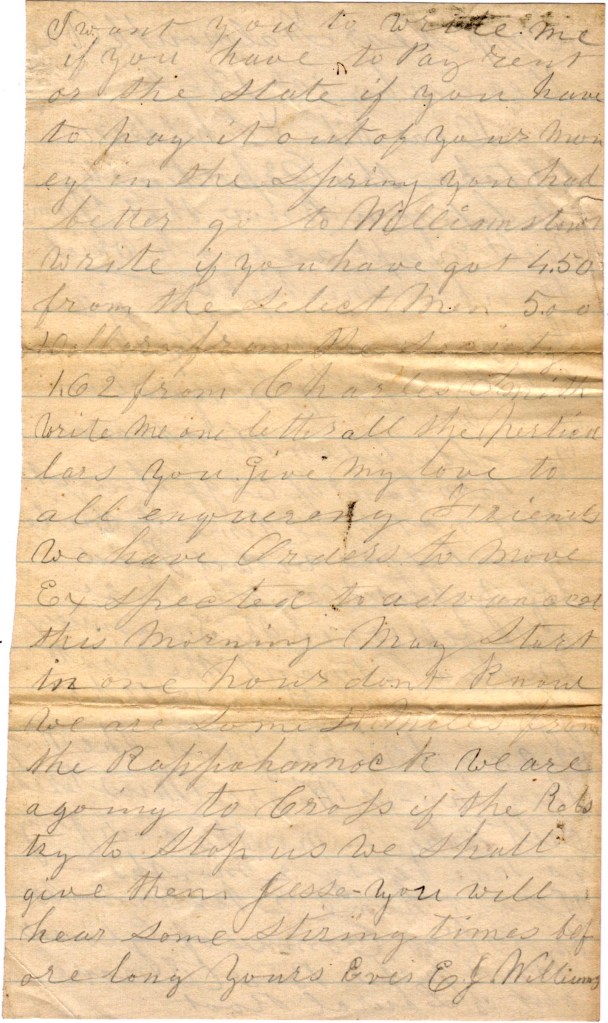

I sent home two testaments by Elias Commer of Glover and a pipe bowl I made out of Laurel root. I want you to write me if you have to pay rent or the State? If you have to pay it out of your money in the spring you had better go to Williamstown. Write if you have got 4.50 from the selectmen, $5 from the Society, $1.62 from Charles Smith. Write me one letter all the particulars. You give my love to all enquiring friends.

We have orders to move. Expected to advance this morning. May start in one hour. Don’t know. We are some four miles from the Rappahannock. We are a going to cross. If the Rebs try to stop us, we shall give them Jesse. You will hear some stirring times before long. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 8

Camp near White Oak Church, Virginia

[Sunday] January 25th 1862

My ever dear wife & children,

I take my pen in hand to write you a few lines. I am well but pretty tired. We went out on a reconnoitering expedition. We were ordered to be in readiness to march last Monday. Did not go until Tuesday morning [January 20th]. We packed up and started about 10 a.m., marched from 12 to 20 miles, camped for the night with orders to make no loud noises or build large fires. Next day in the afternoon, packed up and marched some 3 miles, stacked arms, unslung knapsacks, cartridge boxes & turned mules.

Tuesday the ground was frozen hard enough to move heavy artillery but in the course of the night it commenced raining and the mud was two feet deep in the road made by so many teams, the wheels cutting down to the hubs. We worked until dark helping up pontoon bridges by ropes hitched onto each side of the bridge boat, some 15 men on each side of the road with six mules on the tung, & the way we pulled was a caution through mud some two miles and it rained all the time. Then in the dark went back to camp where we stayed the night before, all wet and tired, I assure you. [We] put up our tents, built fires and it was 2 o’clock before I got dried and the mud rubbed off. Some went to bed in their clothes, wet and muddy. We laid in camp next day. Rained some. Friday we started back to our old camping ground, supported batteries on the road. Arrived in camp about 3 p.m. all tuckered out.

Tell Elthea to send me a paper every two weeks if she can spare a few pennies, only one cent postage.

Lewis Clark is dead. His father was with him & carried his body home. Chester went home with him. I am so tired now I can hardly write. Clark Wilson of Williamstown wounded at the same time & had his leg amputated is dead.

I suppose Melbourne will be out sugaring after school. Then Ellsworth will have to bring in the wood and milk the cow & feed the pig whilst Elthea feeds the hens, washes the dishes, and sweeps the house whilst her Mother rests herself. Give my love to all.

I received the letter you wrote after Lewis was up to your house with the one I wrote him but have not received any since. I have not received any postage stamps yet. I had to borrow one. Send me some soon for I can’t borrow any more. It is hard work to get them. Is Lewis getting the box started? If not, it is not best to send it for I want to sell part of the cheese & don’t want to sell so much as I should have to if we were a going to march. I suppose he was not a going to wait until he writes and gets an answer back. I am expecting one from you both every mail.

I must close so goodbye loved ones. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 9

Camp near White Oak Church, Virginia

February 10, 1863

Dear wife & children,

I take this opportunity to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and in camp. I received yours of January 25th. Will say I have not got my box yet but suppose it is at the Landing but the roads are so bad that they have as much as they can do to get provisions for man and beast. But if the roads improve in a few days, we shall get our Express boxes.

You wrote that you wanted to know what my Captain’s name [was]. It was Oscar A. Hale, nephew of Mr. Currior at the village but he is Major of the 6th. 1st Lieutenant Davis of Brownington is in command [now] & I hope will be Captain. Lt. Dwinnell was promoted to Adjutant, then Captain of Co. C. Lt. Davis married Stewart’s daughter of Brownington. Lewis probably knows Stewarts and Davis.

Perhaps before you hear from me again, I shall be gone from my company to Washington or some other good place. It has been snowing and raining for the past week but since Saturday it has been very fine weather, growing warmer until today it is as warm as June in Vermont. There is no news of importance—only Gen. Smith, our Corps commander, is transferred to the 9th Corps and ordered to report to Fortress Monroe. I am glad it was not the 6th Corps ordered there. This is the Corps the Vermont Brigade belongs to.

I must close for I have got to go out on review at half past 1 p.m. and the mail goes out at 2. Keep up good courage, Susan. That is the way to have good health. Tell Lewis to have my boots made on No. 8 instead of 9, pretty high on the instep. Have the irons on the heels made of steel and a strip across the toes. Have them put on after the boots are dried. If he gets them made by the 1st of April, it will be soon enough. Then do them up and if he cannot get a chance to send them by anyone, put them on board the Express and put them through.

My love to all. So goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 10

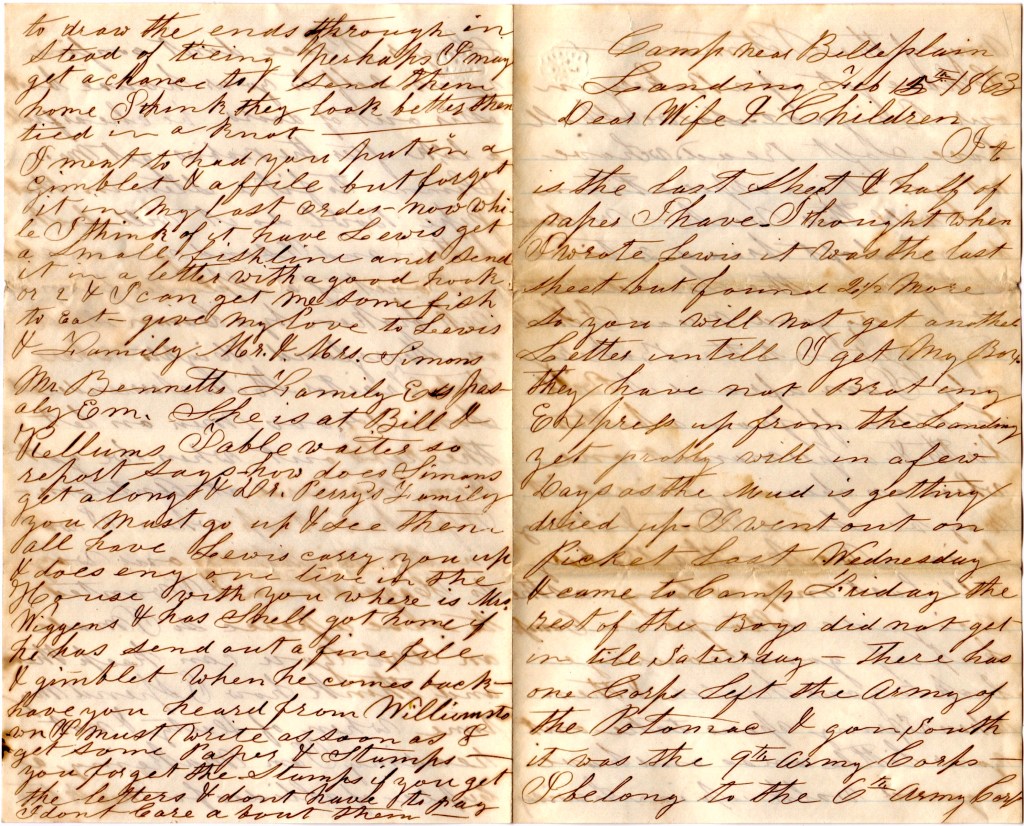

Camp near Belle Plain Landing

February 15, 1863

Dear wife and children.

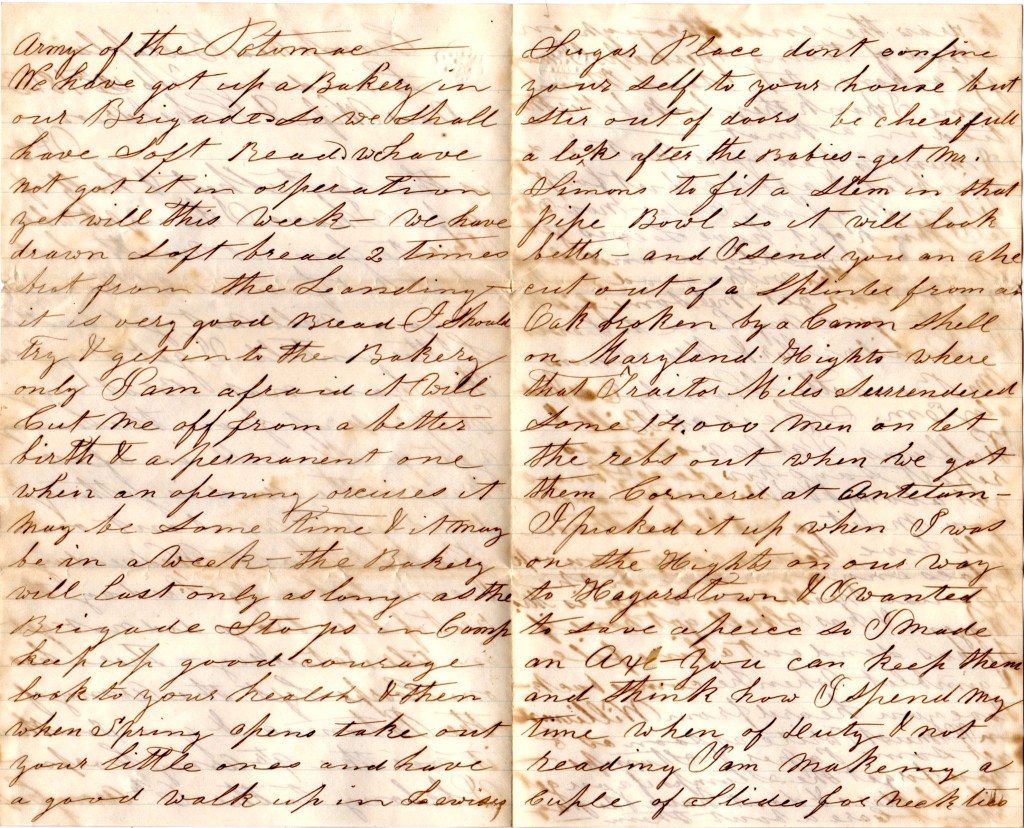

It is the last sheet & a half of paper I have. I thought when I wrote Lewis it was the last sheet but found two and a half more so you will not get another letter until I get my box. They have not brought any Express up from the Landing yet. Probably will in a few days as the mud is getting dried up. I went out on picket last Wednesday & came back to camp Friday. The rest of the Boys did not get in till Saturday. There has one Corps left the Army of the Potomac & gone South. It was the 9th Army Corps. I belong to the 6th Army Corps, Army of the Potomac.

We have got up a bakery in our Brigade so we shall have soft bread. We have not got it in operation yet. Will this week. We have drawn soft bread two times brought from the Landing. It is very good bread. I should try & get into the Bakery only I am afraid it will cut me off from a better berth & a permanent one when an opening occurs. It may be some time & it may be in a week. The Bakery will last only as long as the Brigade stops in camp.

Keep up good courage. Look to your health & then when spring opens, take out your little ones and have a good walk up in Lewis’s sugar place. Don’t confine yourself to your house but stir out of doors. Be cheerful and look after the babies. Get Mr. Simons to fit a stem in that pipe bowl so it will look better. And I send you an axe cut out of a splinter from an Oak broken by a cannon shell on Maryland Heights where that traitor Miles surrendered some 14,000 men and let the Rebs out when we got them cornered at Antietam. I picked it up when I was on the Heights on our way to Hagerstown & wanted to save a piece so I made an axe. You can keep them and think how I spend my time when off duty & not reading. I am making a couple of slides for neck ties to draw the ends through instead of tying. Perhaps I may get a chance to send them home. I think they look better than tied in a knot.

I meant to had you put in a gimlet & a file but forgot it in my last order. Now while I think of it, have Lewis get a small fish line and send it in a letter with a good hook or two & can get me some fish to eat. Give my love to Lewis & family, Mr. & Mrs. Sions, Mr. Bennett’s Family..

Have you heard from Williamstown? I must write as soon as get some paper & stamps. You forgot the stamps. If you get the letters & don’t have to pay, I don’t care about them, but if you have to pay the postage, you have Lewis get me some. I am in hopes they will pay us soon. Probably not until after we are mustered in for pay. Then there will be four months pay due. I suppose little Ellsworth is smart. Tell him that the birds are making their nests out here in Virginia. It is raining some today but is clearing off. In about four weeks they will be working on their farms in Virginia.

I suppose Melbourne will take one of Lewis’s sugar places so you will not have to buy any next year. Well Elthea, I suppose, has taken a school for next summer—probably the big school at the village. Well. Susan, you will have to stay home & feed the tukeys and pig when Elle is milking the old cow. I wish you had your cow up there & I could pop in and see you there all together. Well, God does all things well & in His own time. Perhaps it may be so. What? A Papa meeting? But it will not be so happy as when we meet in Heaven. Have your house set in order, dear Susan, and be in readiness to go at the bridegroom’s coming with your lamp trimmed and burning. Be watchful, hoping and trusting in Him who alone can calm the raging billows & bid the wind to still. Put your trust in God. Give him your heart & not borrow so much trouble & you will feel better than you will to fret so much. All that is lacking is confidence in God. He is able & willing to help you if you will come to Him. Happy is he who endureth to the end.

Kiss the babies for me. With much love. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 11

Camp near White Oak Church, Va.

April 10th 1863

Ever dear wife and children,

It is the greatest pleasure to pen a few thoughts. This is a great age we live in. How mindful God is of us to put it in the minds of men to invent the art of writing, to put characters on paper conveying our thoughts to distant parts of the world. God is good. In Him may we put our trust. He faileth us not. Let us obey Him and bow [in] submission to His will.

I had a letter from Joseph’s family. Mary wrote it. She said Joseph was writing to Little Joseph. She said Betseney was a going to keeping house next week. That will be this present week.

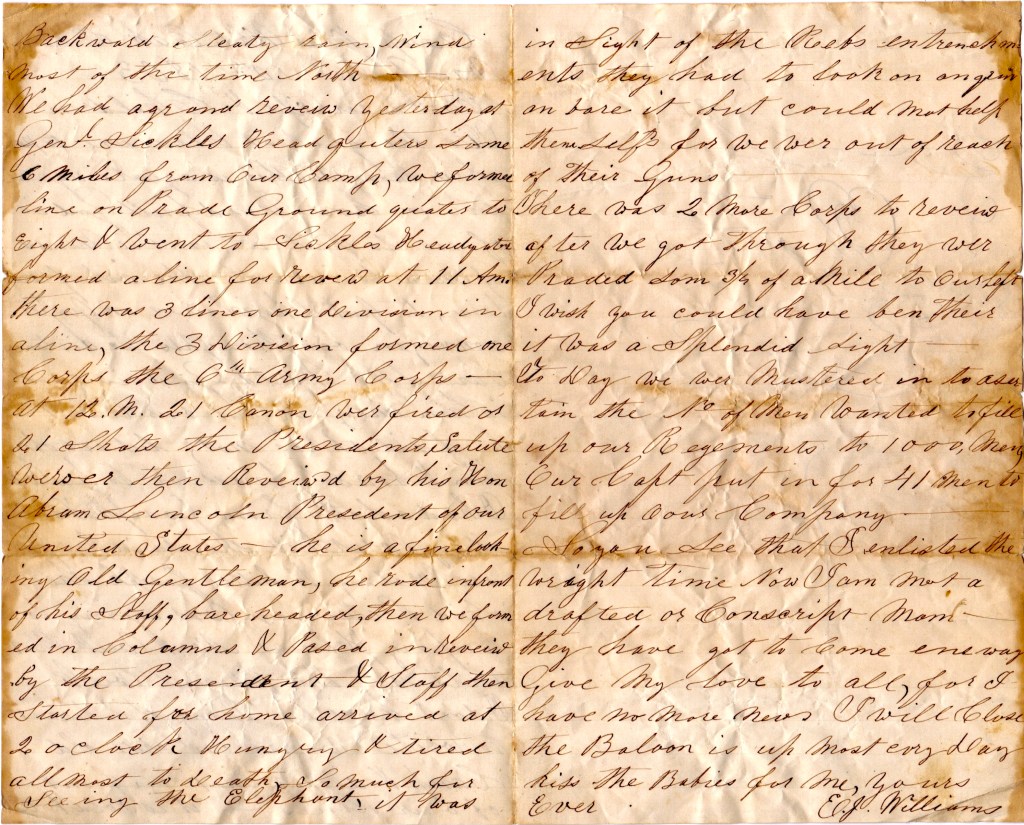

I don’t have anything of interest to write. We are in our old camp & all quiet in front of our lines. It is cold & backward—sleety, rain, wind most of the time North.

We had a Grand Review yesterday at Gen. Sickles’ Headquarters some six miles from our camp. We formed line on parade ground quarter to eight & went to Sickles’ Headquarters, formed a line for review at 11 a.m. There was three lines, one Division in a line. The three Divisions formed one Corps—the 6th Army Corps.

At 12 M, 21 cannon were fired or 21 shots—the President’s salute. We were then reviewed by his Hon. Abram Lincoln, President of our United States. He is a fine looking old gentleman. He rode in front of his staff, bare headed. Then we formed in columns & passed in review by the President and staff. Then started for home. Arrived at 2 o’clock, hungry and tired almost to death. So much for seeing the Elephant. It was in sight of the Rebs entrenchments. They had to look on and grin and bear it but could not help themselves for we were out of reach of their guns.

There was two more Corps to review after we got through. They were paraded some three quarters of a mile to our left. I wish you could have been there. It was a splendid sight. 1

Today we were mustered in to ascertain the number of men wanted to fill up our regiments to 1,000 men. Our Captain put in for 41 men to fill up our company. So you see that I enlisted [at] the right time. Now I am not a drafted or conscript man. They have to come anyway. Give my love to all for I have no more news. I will close.

The balloon is up most every day.

Kiss the babies for me. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

1 The Lincoln Log reports that President Lincoln reviewed the “I, VII, and IX Corps at noon” at Falmouth, Virginia. Elijah’s letter makes it clear this information in erroneous however. The source of this inaccurate information was the [Washington] Evening Star of 10 April 1863. This was actually the 2nd consecutive day that Lincoln had reviewed the troops of four infantry Corps—some 60,000 men. Journalist Noah Brooks witnessed the scene and recalled, “[I]t was a splendid sight to witness their grand martial array as they wound over hills and rolling ground, coming from miles around . . . The President expressed himself as delighted with the appearance of the soldiery . . . It was noticeable that the President merely touched his hat in return salute to the officers, but uncovered to the men in the ranks.”

Letter 12

Camp near White Oak Church

Sunday, May 31st 1863

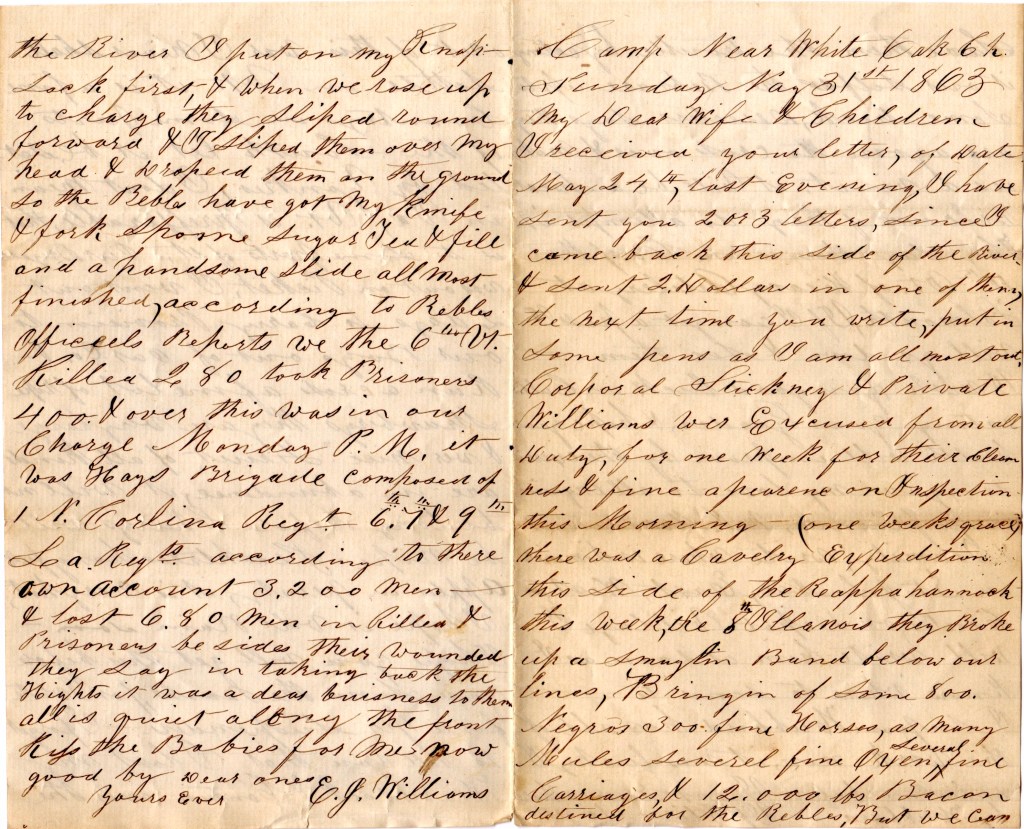

My dear wife & children,

I received your letter of date May 24th last evening. I have sent you two or three letters since I came back this side of the river & sent 2 dollars in one of them. The next time you write, put in some pens as I. am almost out. Corporal Stickney & Private Williams were excused from all duty for one week for their cleanliness & fine appearance on inspection this morning (one week’s grace).

There was a cavalry expedition this side of the Rappahannock this week [by] the 8th Illinois [Cavalry]. They broke up a smugglin’ band below our lines, bringing off some 800 Negroes, 300 fine horses, as many mules, several fine oxen, several fine carriages, and 12,000 lbs. bacon destined for the Rebels. But we can save them the trouble by eating it ourselves. The Rebs are up to some trick. Deserters says they are a going to cross over and make us a visit. It will be a sweet welcome if they do attempt it. They say there is one company of the 11th Vermont of Heavy Artillery at Falmouth. If I. can get a pass, I will go down & see them.

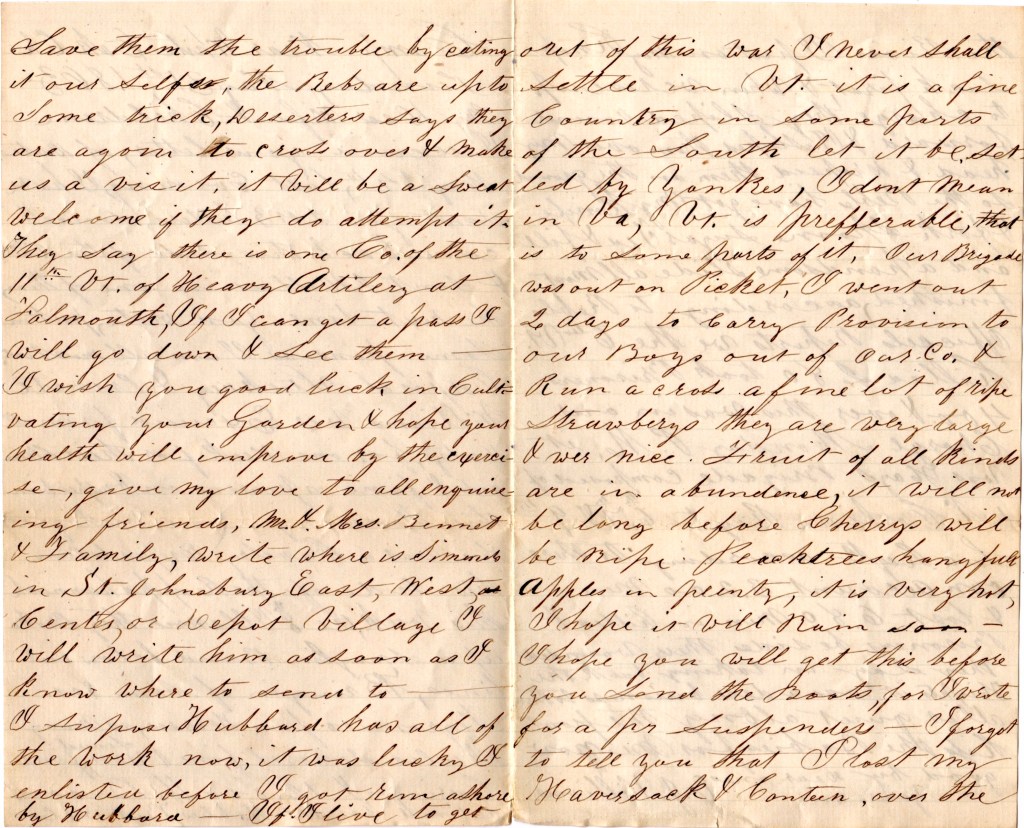

I wish you good luck in cultivating your garden & hope your health will improve by the exercise. Give my love to all. enquiring friends. Mr. & Mrs. Bennet & family. Write where is Simonds in St. Johnsbury East, West, Center, or Depot Village. I will write him as soon as I know where to send to. I suppose Hubbard has all the work now. It was lucky I enlisted before I got run ashore by Hubbard. If I live to get out of this war, I never shall settle in Vermont. It is a fine country in some parts of the South. Let it be settled by Yanks. I don’t mean in Virginia. Vermont is preferable—that is, to some parts of it.

Our Brigade was out on picket. I went out two days to carry provision to our Boys out of our company & run across a fine lot of ripe strawberries. They are very large & were nice. Fruit of all kinds are in abundance. It will not be long before cherries will be ripe. Peach trees hang full. Apples in plenty. It is very hot. I hope it will rain soon.

I hope you will get this before you send the boots for I wrote for a pair of suspenders. I forgot to tell you that I lost mu haversack & canteen over the river. I put on my knapsack first and when we rose up to charge, they slipped round forward and I slipped them over my head & dropped them on the ground so the Rebels have got my knife & fork, spoon, sugar, tea, and fill, and a handsome slide almost finished. According to Rebel Official Reports, we—the 6th Veront—killed 280, took prisoners 400, and over this was in our charge Monday p.m. It was Hays’ Brigade composed of 1st North Carolina Regiment, 6th, 7th, and 9th Louisiana Regiments according to their own account, 3,200 men & lost 680 men in killed & prisoners besides their wounded. They say in taking back the Heights it was a dear business to them.

All is quiet along the front. Kiss the babies for me. Now goodbye, dear ones. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 13

Camp on the field near Fredericksburg

[Sunday] June 7th 1863

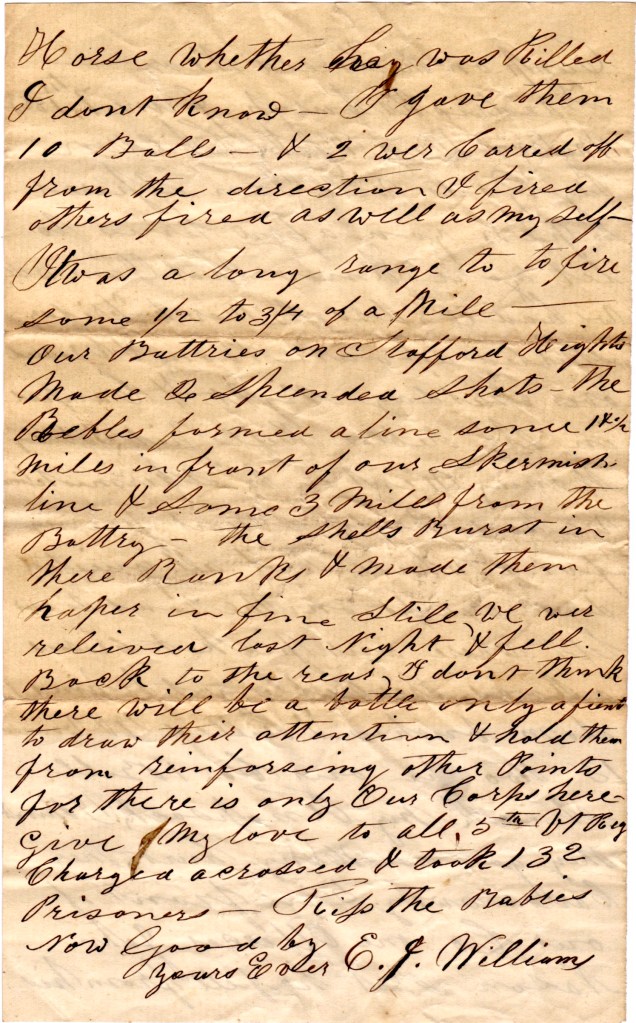

My ever dear wife and children.

By God’s will, I am spared to pen you a few lines to let you know that I am well. We had orders to march Friday. Started about noon & crossed over Friday night and camped in the Rebel’s rifle pits. Saturday morning [6 June] went on to skirmish line. We had pretty smart firing for awhile, but all. quieted down except on the road to our left where our picket crosses a road. The Rebels got behind some bushes & killed four and wounded 13—two of our company. One ball struck my knapsack. I think they got as many hurt. They carried away five in front of our company. One officer, John Nason, shot. He fell from his horse. Whether he was killed, I don’t know. I gave them ten balls and two were carried off from the direction I fired. Others fired as well as myself. It was a long range to fire—some half to three quarters of a mile.

Our batteries on Stafford Heights made two splendid shots. The Rebels formed a line some one and a half miles in front of our skirmish line & some three miles from the battery. The shells burst in their ranks & made them scamper in fine style. We were relieved last night & fell back to the rear. I don’t think there will be a battle—only a feint to draw their attention & hold them from reinforcing other points for there is only our Corps here. 1

Give my love to all. 5th Vermont Regiment charged across & took 132 prisoners. Kiss the babies. Now goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

1 The fighting at Fredericksburg on 6 June 1863 involved a reconnaissance by Union forces under General John Sedgwick, probing Confederate positions near the Rappahannock River. This action, part of the larger Gettysburg Campaign, was a small skirmish known as the Battle of Franklin’s Crossing or Deep Run. The Union probe was repulsed by Confederate troops under Gen. A. P. Hill’s 3rd Corps who were left to cover Lee’s exodus from the area as he stole a march northward on the Union army.

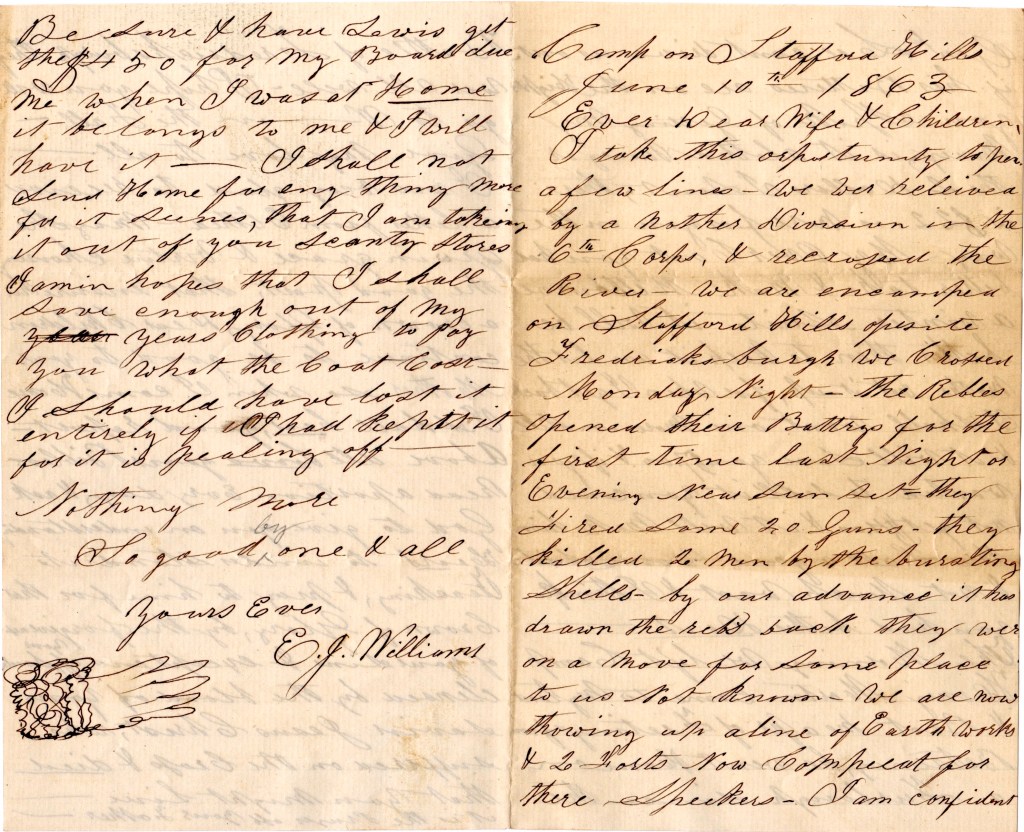

Letter 14

Camp on Stafford Hills

June 10th 1863

Ever dear wife & children,

I take this opportunity to pen a few lines. We were relieved by another Division in the 6th Corps & recrossed the river. We are encamped on Stafford Hills opposite Fredericksburg. We crossed Monday night. The Rebels opened their batteries for the first time last night or evening near sunset. They fired some 20 guns. They killed two men by the bursting shells. By our advance, it has drawn the Rebs back. They were on a move for some place to us not known. We are now throwing up a line of earthworks & two forts now completed for their speakers. I am confident Gen. Lee can’t drive us out if his batteries are on the Heights.

You spoke of getting my money. Is it allotted money or the 2 dollars I sent? There is $22 or more for you on the way. My overcoat you had better take and make Melbourne a winter suit. It will be better than to keep it and let the moths eat it up for when I get back, I shall want one more in style & it will save you $7 & if you wanted to sell it, you could not get $4 & it will make him this fall a good warm suit & not much waste & I think you had better do it.

The morning we left camp, Henry Martin came to my tent and brought me a pair of Feetings from Betseney. He went home on a furlough since the Battle of Fredericksburg. They were all well. I hope you will go to W. in the fall. Give my love to all.

I was glad to receive a letter from Elthea. May she grow in grace & virtue choosing the good part, that ensure her a crown of Glory. Dear children, continue to be good to your Mother so when I come home, I shall hear good reports. Above all, love your Bibles. Read a portion every day & ask God to give you an understanding heart to understand its teaching & pray to Him for that crown of Glory, by the forgiveness of your sins and exceptions of your souls, cleansed by the blood of your Savior, Jesus Christ, who suffered on the cross and died that you might live. It is the prayer of your Father.

Be sure and have Lewis get the $4.50 for my board due me when I was at home. It belongs to me & I will have it. I shall not send home for anything more for it seems that I am taking it out of your scanty stores. I am in hopes that I shall save enough out of my year’s clothing [allowance] to pay you what the coat cost. I should have lost it entirely if I had kept it for it is peeling off. Nothing more so goodbye one and all. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 15

Camp near the Battleground Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

July 5, 1863

Dear Wife & Children,

By God’s Providence, I am spared whilst thousands are laying around me—the dead, dying, and wounded. Our Brigade has not been in the hottest of the fight. It lays on the extreme left. we went from Bristol Station 23 on picket about 5 miles from the station. Orders came on the 25th to march at 4 p.m. to join the Brigade back to Centerville. Camped there about two in the morning. After marching some 12 miles in the night before, started in the morning 26th at 4 a.m., passed the 2nd Vermont Brigade for Edwards Ferry on the Potomac River near Poolsville, Maryland. Arrived on the 27th where the 10th Vermont Regiment encamped last winter but moved the day before we got there so I did not see Joseph. The 2nd Vermont Brigade passed us here to join Gen. Reynolds’ Corps.

We started the 28th for Pennsylvania. Arrived on the battle ground July 2nd after a long, tedious march. The last three days we marched night and day, some 90 miles. The 2nd we started two miles from Manchester, Maryland, about half past 12 at night & arrived on the battle ground about 5 p.m., marching some 35 miles. The 1st of July, Gen. Reynolds was killed. There was three days fighting [?]. We took some 6 to 8,000 prisoners. It was a hotly contested battle. We have drove them back. Gen. Longstreet & Hill—Rebels—are reported killed. We are ordered to be in readiness to move. So goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

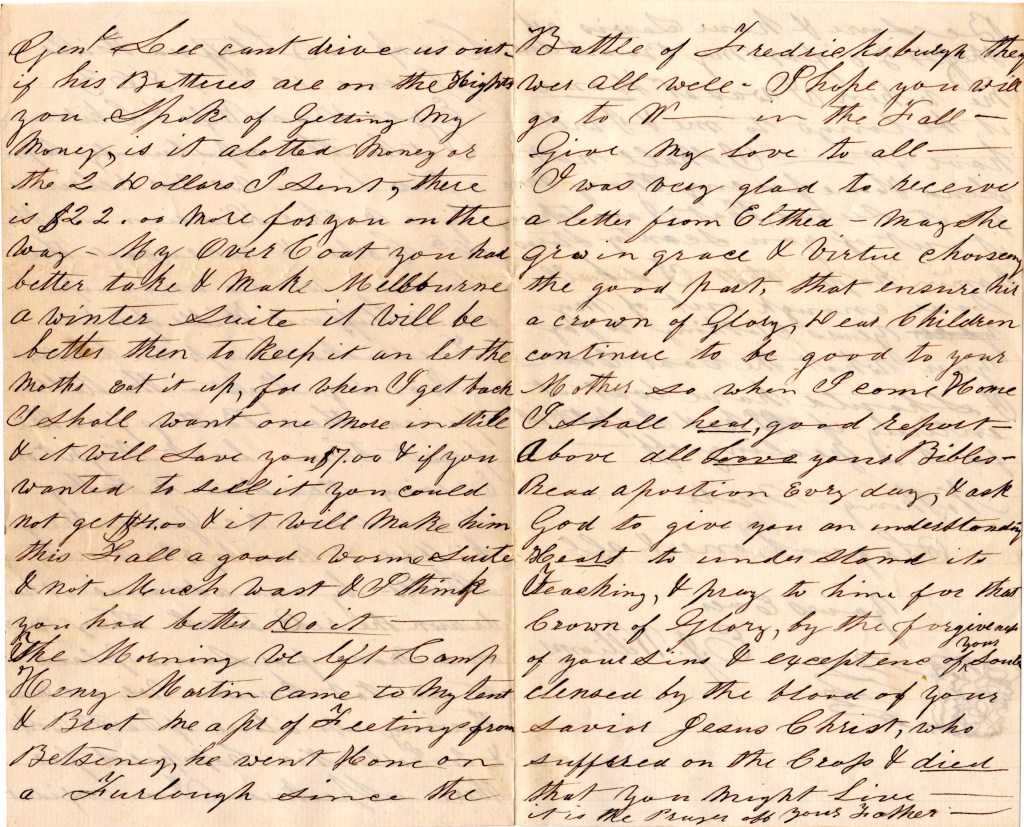

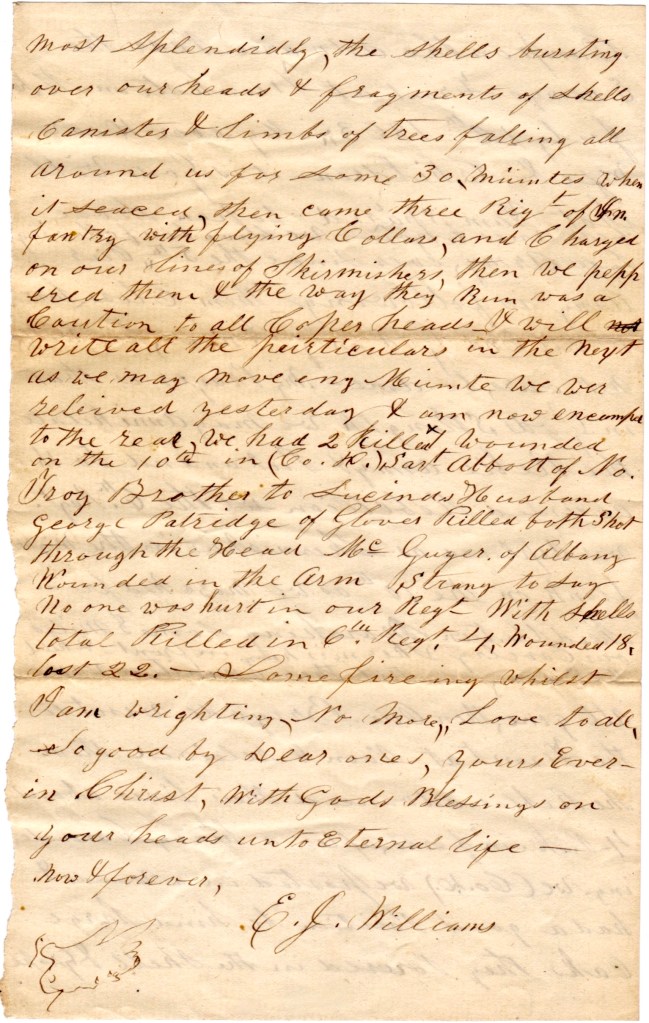

Letter 16

Camp on the advance near the enemy’s front at Funkstown, MD

July 12th 1863

My ever dear wife & children,

It is God’s will that I am spared to pen these few lines to you. We have been following Lee’s army ever since the 5th. Our army is following them close. How it will end, God only knows. His will, not ours, be done. My prayer is that in God’s strength we may annihilate the Rebel army & put an end to this accursed Rebellion.

The 6th [Vermont] Regiment was deployed as skirmishers on the right flank on the 10th as we marched from Middletown marching some 8 miles, our cavalry skirmishing in front, & held the enemy until their ammunition was all gone. Then our Brigade went to the front at noon and relieved them. The Rebels advanced their lines about 4 p.m. in force after a heavy cannonading. We (Co. D) posted in a woods & had a good position behind large oaks. They poured in the shell & grape most splendidly, the shells bursting over our heads & fragments of shells, canister, and limbs of trees falling all around us for some 30 minutes. When it ceased, then came three regiments of infantry with flying colors and charged on our lines of skirmishers. Then we peppered them & the way. they run was a caution to all Copperheads.

I will write all the particulars in the next as we may move any minute. We were relieved yesterday & am now encamped to the rear. We had two killed & wounded on the 10th in Co. D—Sergt. Abbott of North Troy, brother to Lucinda’s husband, [and] George Patridge of Glover killed, both shot through the head. McGuyer of Albany wounded in the arm. Strange to say, no one was hurt in our regiment with shells. Total killed in the 6th [Vermont] Regiment, [killed] 4, wounded 18, lost 22.

Some firing whilst I am writing. No more. Love to all. So goodbye dear one. Yours ever in Christ. With God’s blessings on your heads until eternal life. Now & forever. — E. J. Williams

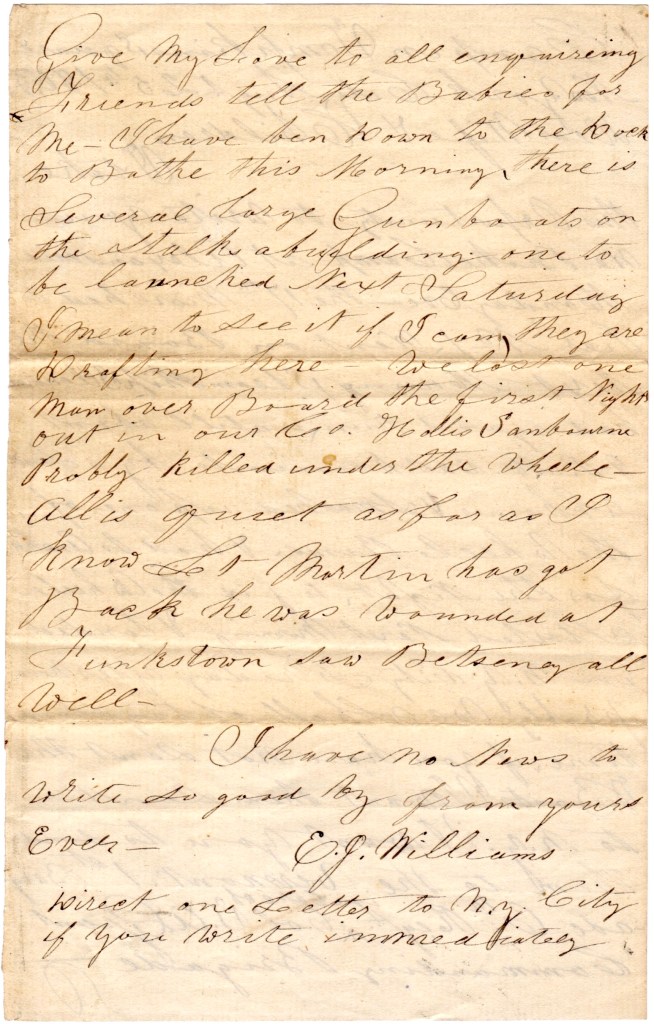

Letter 17

Camp on Tompkins Square, New York 1

[Tuesday] August 25th 1863

Dear wife and children,

I take this opportunity to write you. We broke camp at Alexandria Monday eve—the 17th, marched to Pier No. 1, [and] went on board the next morning steamship Illinois. [We] had a good run until about 9 p.m. [when we] was run into by a small schooner & smashed up one of the wheel rims & had to anchor for the night to fix the wheels. Started next morning & landed in New York City Friday afternoon. Probably we shall stay some time.

If you have not sent the boots, I want them sent to New york. I want you to send them to the Vermont 1st Brigade, 6th Regiment, in care of Col. T. A. Grant, Commanding Brigade.

Give my love to all. enquiring friends. Tell the babies for me.

I have been down to the dock to bathe this morning. There is several large gunboats on the stalks a building—one to be launched next Saturday [August 29th]. I mean to see it if I can. 2

They are drafting here. We lost one man overboard the first night out in our company. Hollis [S.] Sanborn. Probably killed under the wheel. 3

All is quiet as far as I know. Lt. Martin has got back. He was wounded at Funkstown. Saw Betsenay all well. I have no news to write so goodbye. From yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Direct your letter to N. Y. City if you write immediately.

1 The square, first known as Clinton, was mapped in 1833 and renamed by the State legislature for former governor Daniel D. Tompkins (1774-1825). The City acquired Tompkins Square by condemnation in 1834. Swampland was filled, graded, and landscaped between 1835 and 1850. Gas lights were installed in the park in 1849. In 1851 a large fountain (later removed) was built in the park by the Croton Aqueduct Department, and the park was fenced in 1858. By 1860 the park had taken on a more attractive appearance. Trees had been planted around the edges and flagstone paths provided pleasant walkways that directed circulation around the square. The city planted shrubbery and flowers and built a central fountain. Iron fences were installed to protect the planting from horses, pigs, goats, and small children. Unfortunately, the encampment by Civil War soldiers posted in the park during the 1863 draft riots destroyed much of the landscaping. The area around the square, know as the Dry-Dock neighborhood, was a center for New York’s shipbuilding industry before the Civil War.

2 This may have been the USS Miantonomoh, a double turreted ironclad monitor built for the US Navy in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Newspaper accounts confirm it was launched on Saturday, 15 August 1863, however.

3 Hollis Smith Sanborn (1839-1863) of Canada enlisted in Co. D, 6th Vermont Infantry on 4 October 1861. He died of an accidental drowning on the night of 18 August, 1863. A record in his pension file states that Hollis was “washed overboard” in the collision on Chesapeake Bay described by Elijah. The location of the collision was off Smith Point Lighthouse. The schooner was loaded with marble and the impact so severe that it jarred the Illinois.

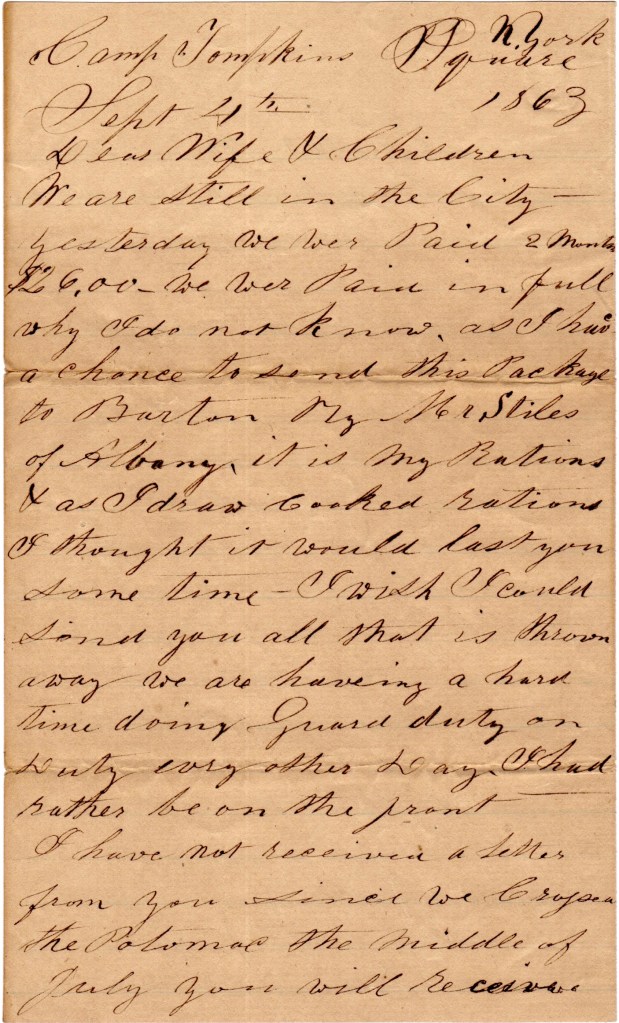

Letter 18

Camp Tompkins Square, New York

September 4, 1863

Dear wife & children,

We are still i the city. Yesterday we were paid two months, $26. We were paid in full. Why, I do not know. As I have a chance to send this package to Barton by Mr. Stiles of Albany, it is my rations & as I draw cooked rations, I thought it would last you some time. I wish I could send you all that is thrown away.

We are having a hard time doing guard duty. [We are] on duty every other day. I had rather be on the front.

I have not received a letter from you since we crossed the Potomac the middle of July.

You will receive in this $20 & write as soon as received. I have written for my boots to be sent to New York City, 1st Vermont Brigade, 6th Regiment Vermont Vol., Camp on Tompkins Square.

Give my love to all enquiring friends, if any there be. There is no news of importance. It has been fine weather since we left the Army of the Potomac. Be sure and write for I shall be anxious to know if the package & money arrives safe. I suppose you have all the green stuff you want from your garden. I have had two years boiled corn & paid four cents.

As I am in a hurry, I will bid you all goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

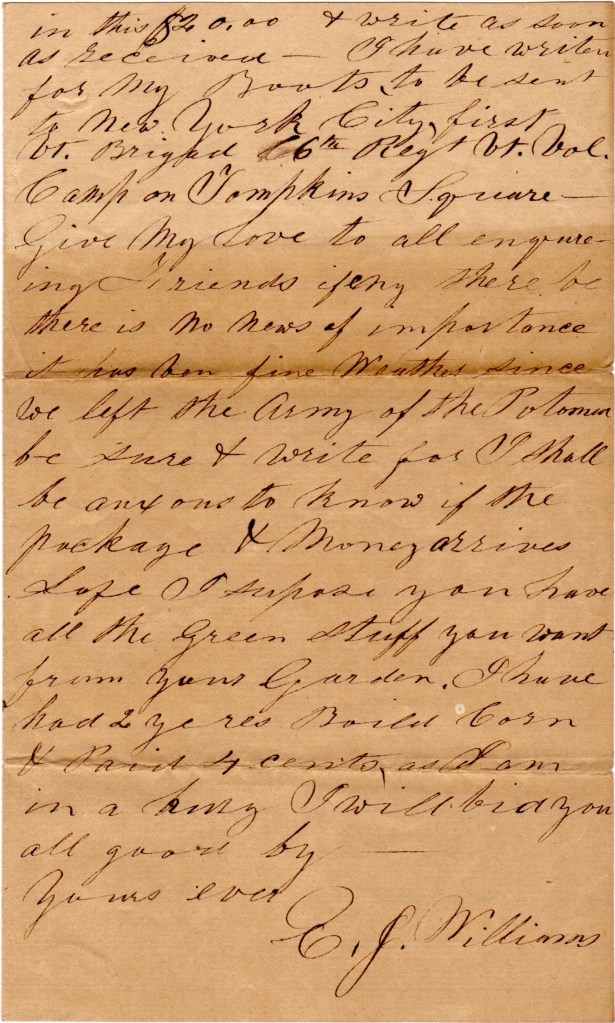

Letter 19

Camp near Rappahannock Station

November 25th 1863

Dear wife & children,

I take this opportunity to inform you of my health is good. We had orders to move yesterday morning at 6 a.m. [but] it commenced raining in the night and was countermanded 48 hours, so we move (if weather permits) early tomorrow morning. Where to, time will tell. I think towards Richmond. the campaign will be short as it is getting late in the season. It seems the rebels are falling back.

I send you $1.50 cents. I was in hopes they would pay us before now. Kiss the babies for me. Love to all. I will write soon again. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

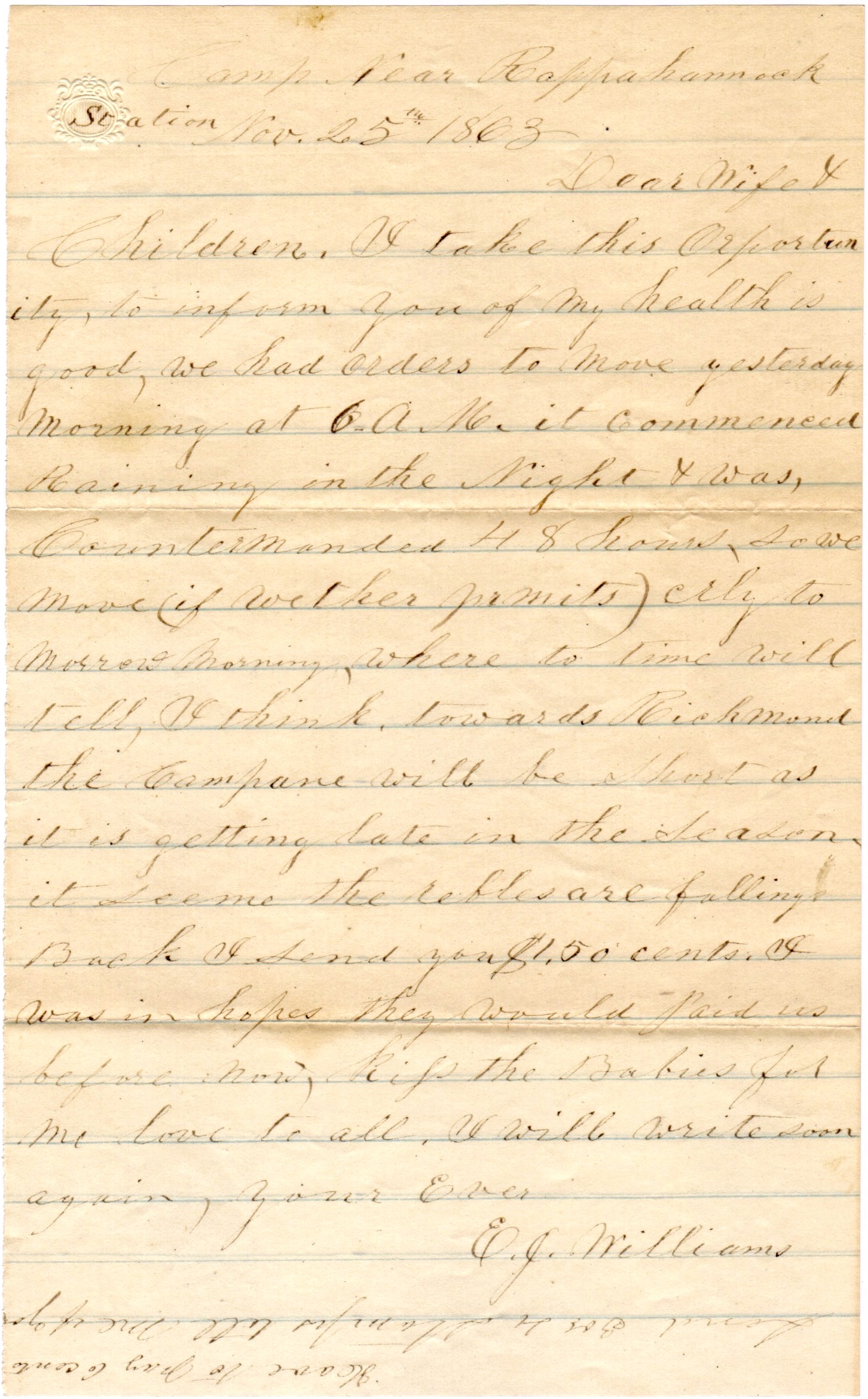

Letter 20

Camp near Brandy Station

December 20th 1863

Ever dear wife & children.

I received your letter yesterday. Was glad to hear from you. Probably you will get the one I sent you the other day. We were paid off and I sent you some more money. I wrote to Elthea & sent her $1. I sent her 35 cents before. She said she had 140 cents & sent me two postage stamps, I will supply her with money so you. can keep all I send you. I don’t want the money so don’t fret. Tell Lewis to see the Express agent and if he can’t find them, get the pay and send another pair boxed up and directed to Capt. M. Warner Davis, Co. D, 6th Vermont Vol. & put in a piece of cheese if you have a chance. Don’t start the box before the first of January but if they get the boots, I don’t want a box. They can find them by that time & get them to me. If not by the first of January, get a new pair made and send if not ordered otherwise.

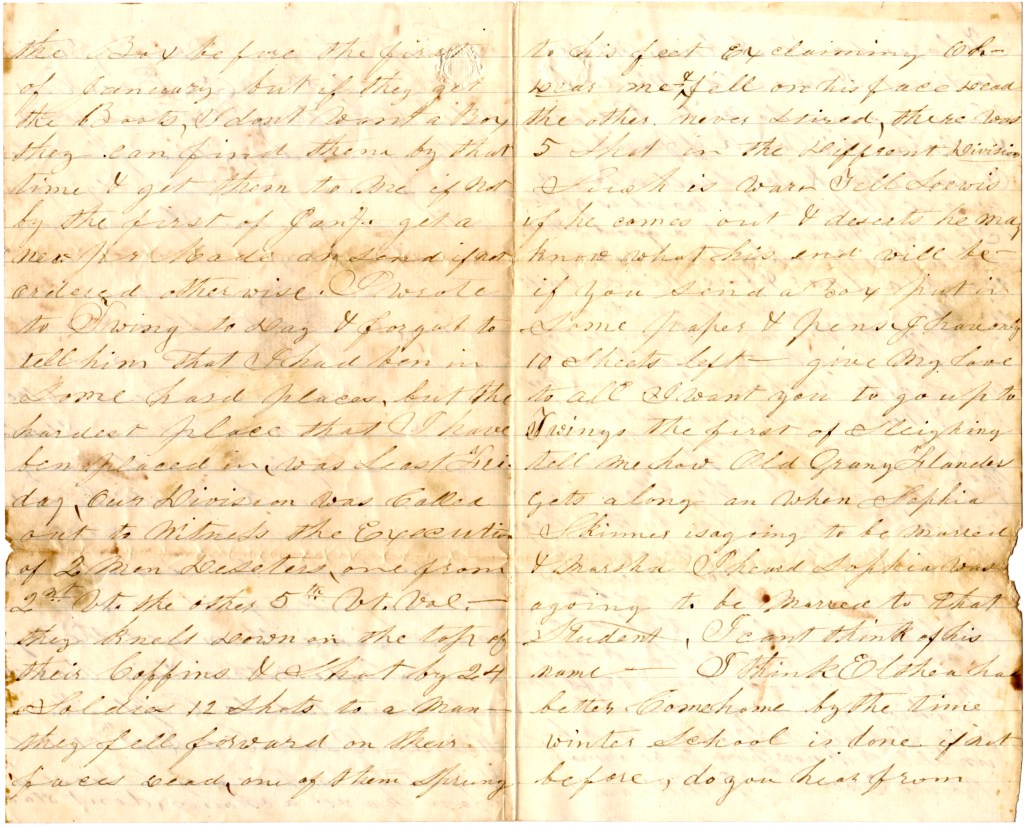

I wrote to Swing today and forgot to tell him that I had been in some hard places, but the hardest place that I have been in was last Friday. Our Division was called out to witness the execution of two men—deserters. One was from the 2nd Vermont, the other 5th Vermont Volunteers. They knelt down on the top of their coffins and shot by 24 soldiers, 12 shots to a man. They fell forward on their faces dead. One of them sprung to his feet exclaiming, “Oh dear me!” and fell on his face dead. The other never stirred. There was 5 shot in the different Divisions. Such is war. Tell Lewis if he comes out and deserts, he may know what his end will be. 1

If you send a box, put in some paper & pens. I have only ten sheets left. Giver my love to all. I want you to go up to Twiny’s the first of sleighing. Tell me how Old Granny Flander gets along and when Sophia Skinner is going to be married, and Marsha. I heard Sophia was a going to be married to that student [but] I can’t think of his name. I think Elthea had better come home by the time winter school is done if not before. Do you hear from Florenda? If I knew where to direct, I would write her. I am a going to write Betseney and Mary this week if possible.

I don’t think we shall stay a great while for wood is getting scarce. I have got a good shanty built up of boards and ends, except a door & fire place built in Old Virginia style on the outside of the house. I can sit by my fire, cook my meat and make my coffee, & when it storms, keep dry and warm. Such men as I the captain says ought to [be] soldiers that will fix up things so nice and comfortable. They had inspections of quarters today by the Major and Doctor. My tent was the only one they went into. It is not decided yet about reenlisting yet. Shall know before the first of January. I don’t think of any more so goodbye & kiss the babies… Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

1 The two Vermont soldiers executed on 18 December 1863 were George E. Blowers of the 2nd Vermont and John Tague of the 5th Vermont. The blog “Tales from the Army of the Potomac” carried a description of the executions:

“Meanwhile, over in the camp of the 2nd Division, 6th Corps, a dual execution occurred, this one for Private John Tague and Private George Blowers. As always, the division assigned to carry out the killings formed up in a three-sided box facing the graves. The soldiers who observed the execution stood at “order arms” for about one hour until two ambulances drove onto the site, bearing the condemned men and their coffins. One of the soldiers in line, Private Wilbur Fisk, wrote, “It seemed as if some horrible tragedy in a theater were about to be enacted, rather than a real preparation for an execution.” The most alarming thing about it was the behavior of John Tague, who, as the orders of execution were being read, threw his hat onto the ground in bold defiance. Two chaplains stepped to the sides of Tague and Blowers, bade them kneel, and delivered a prayer. After that, the sergeant of the guard conducted them to their coffins and made them kneel again. He put two massive rings around their necks which suspended targets on their chests. (By now, authorities had realized that the firing squads needed to be coaxed into taking a kill shot.) Strangely, this execution contained no reserve. That is, no one expected the prisoners to live beyond the first volley. Two platoons of men faced each prisoner, and the prisoners were not blindfolded. Private Fisk recorded the final moments: “Blowers had been sick, his head slightly drooped as if oppressed with a terrible sense of the fate he was about to meet. He had requested that he might see his brother in Co. A, but his brother was not there. He had no heart to see the execution, and had been excused from coming. Tague was firm and erect till the last moment, and when the order was given to fire, he fell like dead weight, his face resting on the ground, and his feet still remaining on the coffin. Blowers fell at the same time. He exclaimed, “O dear me!” struggled for a moment, and was dead. Immediately our attention was called away by the loud orders of our commanding officers, and we marched in columns around the spot where the bodies of the two men were lying just as they fell. God grant that another such punishment may never be needed in the Potomac Army.”

This was Private Fisk’s first execution. Like many who witnessed such tragic scenes, he never forgot what he saw: “I never was obliged to witness a sight like that before, and I sincerely hope a long time may intervene before I am thus called upon again. . . . These men were made examples, and executed in the presence of the Division, to deter others from the same crime. Alas, that it should be necessary! Such terrible scenes can only blunt men’s finer sensibilities and burden them the more; and Heaven knows that the influences of a soldier’s life are hardening enough already. . . . I have seen men shot down by scores and hundreds in the field of battle, and have stood within arm’s reach of comrades that were shot dead; but I believe I never have witnessed that from which any soul shrunk with such horror, as to see those two soldiers shot dead in cold blood at the iron decree of military law.”

Letter 21

Camp near Brandy Station

December 27th 1863

Eve dear wife & children,

I take this opportunity to pen you a few lines. I have not heard from my boots yet & if Lewis gets me another pair made, send them in a box & a few pounds of cheese, some paper and pens. I have got envelopes enough. One pair suspenders and one paper of carpet tacks—not very large size. If he can’t get pay for the boots sent. I don’t know as he had better get any more for it is taking things from you which you need & I can get along without them some way. Give my love to all.

Some of the old Boys are reenlisting & Lucien Sanborn has reenlisted & I send two balls from the Button Wood tree. Have them varnished & then they will always keep clean. If they get dirty, you can wash them. If you send another pair of boots, send them as soon as possible directed to Capt. M. Warner Davis, Co. D, 6th Regt. Vermont Vol., Washington D. C. Put them in a strong box.

There is no news of importance. All quiet on the front. Kiss the babies for me. I suppose Melle is a going to school and little man does the thrashing and chops the wood & brings in the water. Well goodbye, Susan and all. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 22

Camp near Brandy Station

January 9th 1864

Dear wife & children,

I received a letter from you & Lewis. As to reenlisting, I have not been in the service by 10 months to reenlist. All that can reenlist that is in the service must have less than 15 months to serve before their present term of service expires. Next September, perhaps there will be a chance if this war is not closed. I hope by the blessings of God it will be. I for one do not wish to see anymore fighting, but if fighting is to be done, I for one am ready any time called upon.

There is no news. Everything is quiet on our front. Love to all. Kiss the babies & goodbye. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

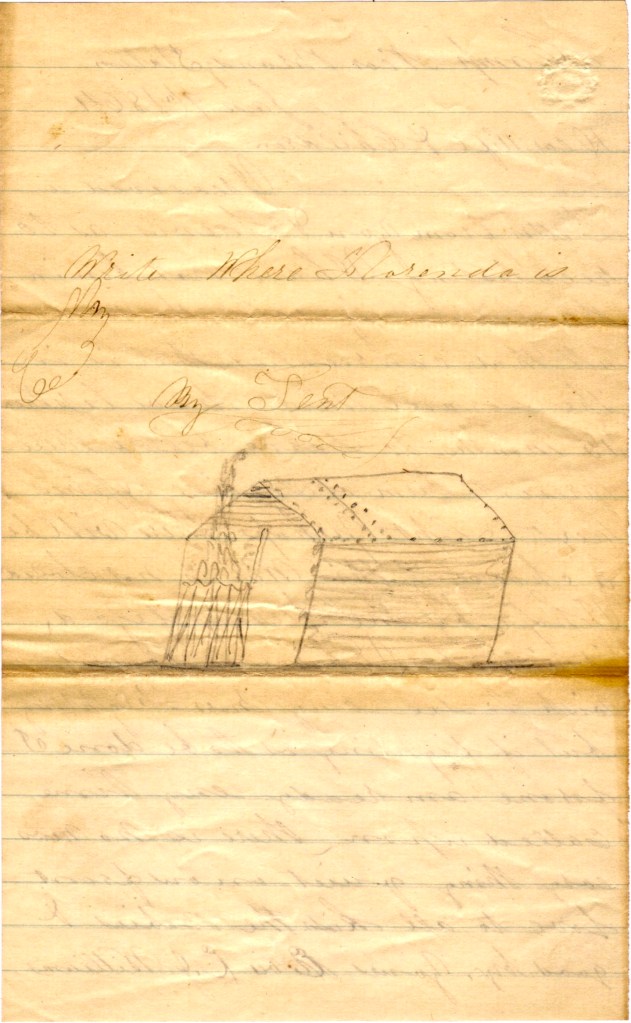

Write where Florenda is. My tent.

Letter 23

Camp near Brandy Station, Va.

January 23rd 1864

Dear wife & children.

I take this opportunity to pen you a few lines to inform you that it is muddy. I went over to the 10th [Vermont] to see Joseph yesterday, some four miles from our camp. I saw Elvira’s husband, Perry Hopkins. Elvira has gone home to his Father’s. Mr. Simons lives in Rutland. The people in Williamstown are all well. Betseyney is keeping house for George Ainsworth. George is out in the army. I have not seen him yet. I have received no letters for some time.

We have built us a chapel & dedicated it last night. Text 1st Romans, 1st Chapter, 16th Verse. Music by the choir. One lady present. We have prayer meetings & bible class every Tuesday evening. Last Sunday I saw Judge french. I did see him but a few minutes. I was on Brigade guard & just got into camp as he left. If I had known it the night before, I should been glad to had a chat with him. He said Mace Kimball, Mark Nuter, Jerry Drew, and some others I don’t remember but I did not see them.

The weather has been very cold—not much snow. We have 26 recruits come in to our company since the Old Boys went home. All is quiet on the front.

Love to all. If Lewis has not got any more boots made, [tell him] not to for I have made up my mind not to have any. One pair is enough to lose as much as I can afford to lose. Keep the money & buy something for yourself and children. Kiss them for me. Yours respectfully. Ever, — E. J. Williams

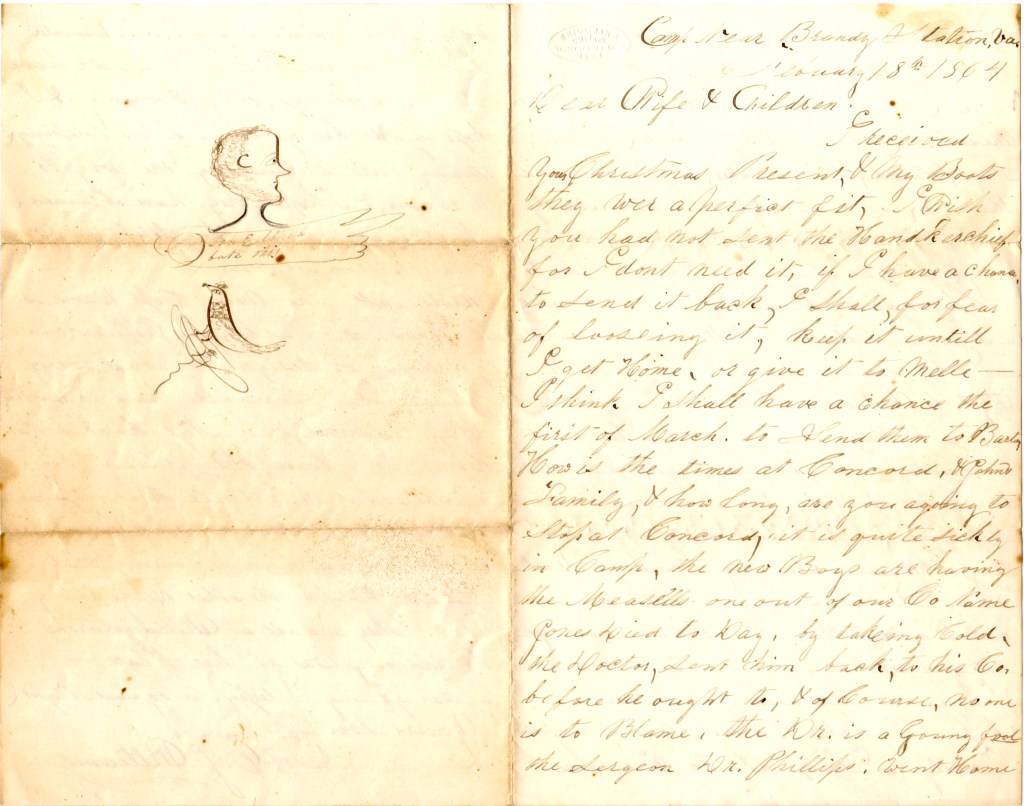

Letter 24

Camp near Brandy Station, Virginia

February 18th 1864

Dear wife & children,

I received your Christmas present & my boots. They were a perfect fit. I wish you had not sent the handkerchief for I don’t need it. If I have a chance to send it back, I shall, for fear of losing it. Keep it until I get home or give it to Melle. I think I shall have a chance the first of March to send them to Barton. How is the times at Concord & John’s family & how long are you a going to stop at Concord?

The new Boys are having the measles. One out of our company named Jones died today by taking cold. The doctor sent him back to his company before he ought to & of course no one is to blame. The doctor is a young fool. The surgeon, Dr. Phillips, went home. After he left, this fool sent Jones to his company & it has cost him his life. It is very healthy except the measles.

It is very cold, cutting west wind. It is sharp. It pierces one through. It snowed the other day but it is all gone & the ground is dry and frozen some.

I have written to Florenda & Lusia. Have not received any letters from Williamstown yet. I tell you one thing, I am a going to write to William this week if I don’t have to much duty to do. I have not been on guard for 15 days (up to yesterday). Come off duty this morning, same difference, then being on duty every 3rd day. We are clearing land for Uncle Sam. We have to go some two miles for our wood. The Boys have got some rot gut and are pretty noisy.

I hope to hear from you. soon. Kiss the babies for me. Love to John’s family. I expect to see some very nice painting from our daughter. I hope to see some soon.

We have prayer meetings every evening & I hope God has given us His blessing & many are enquiring the way to Heaven & hope they have obtained mercy in giving themself to Jesus who clenseth from all sin.

Write all the news. Capt. Davis is at home on furlough. Officers can go home or resign, & do about as they please but privates have to knuckle [down]. Capt. Dwinnell & Lt. Nye have been at home to Glover. They said they spoke about Sartwell running away & the people had not heard of it & they saw him drawing wood. I sasw Joseph the other day at my tent. They are all at Williamstown. Betseney was at his place. I am getting sleepy so good night. Yours ever, — Corp. E. J. Williams

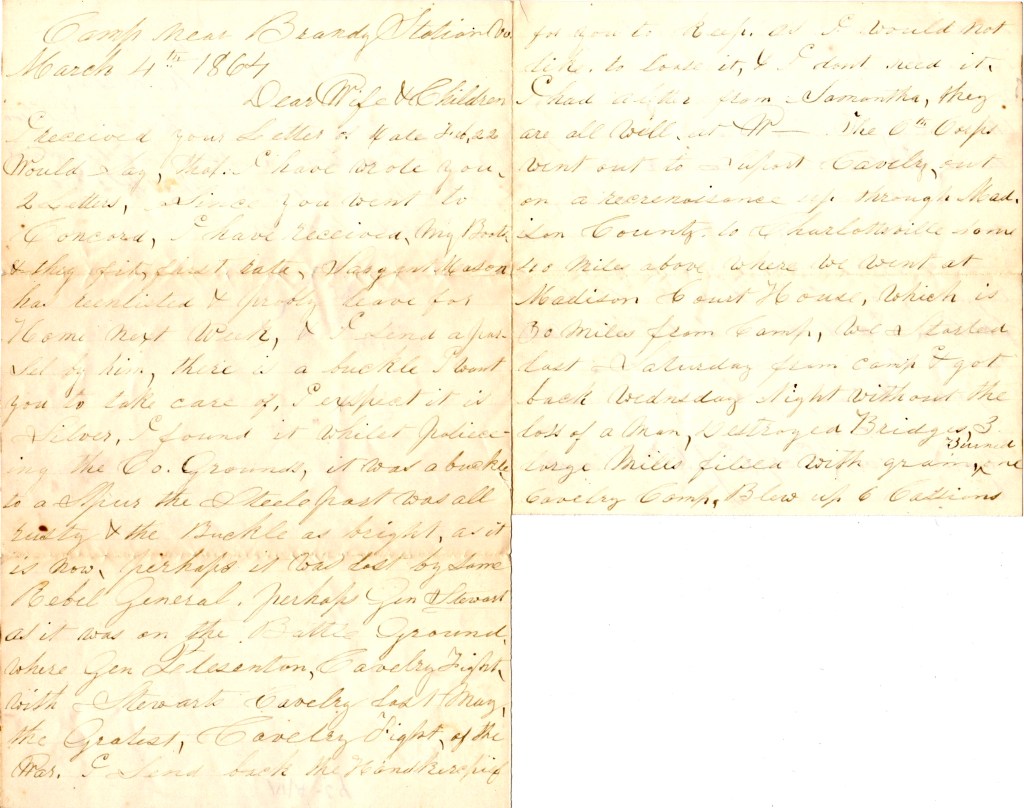

Letter 25

Camp near Brandy Station, Va.

March 4th 1864

Dear wife & children,

I received your letter of [ ] February 22. Would say that I have wrote you two letters since you. went to Concord. I have received my boots & they fit first rate. Sergeant Mason has reenlisted & [will] probably leave for home next week & I send a parcel by him. There is a buckle. I want you to take care of [it]. I expect it is silver. I found it whilst policing the company grounds. It was a buckle to a spur. The steel part was all rusty & the buckle as bright as it is now. Perhaps it was lost by some Rebel General, perhaps General Stuart as it was on the battle ground where Gen. Pleasanton [had his] cavalry fight Stuart’s cavalry last May—“the greatest Cavalry fight of the War.” I send back the handkerchief for you to keep as I would not like to lose it & I don’t need it.

I had a letter from Samantha. they are all well at Williamstown. The 6th Corps went out to support cavalry out on a reconnoissance up through Madison county to Charlottesville some 40 miles above where we went at Madison Court House, which is 30 miles from camp. We started last Saturday from camp & got back Wednesday night without the loss of a man, destroyed bridges, three large mills filled with grain, burned one cavalry camp, blew up six caissons, captured 50 prisoners, & 500 horses and brought in a lot of Negroes without losing a man. Had four wounded.

I wish you would get me a watch chain hook costing some ten cents. Brads or Steel, I don’t care which. Get a good stout serviceable one. Give my best regards to all and kiss the babies for me. I don’t know but Elthea will resent being called a baby. God’s blessing be with you all. So goodbye. Yours ever, — Corp. E. J. Williams

P. S. When I got into camp, I found Messrs, J, K. DRew, Thomas Baker, Matherson & Nelson from Barton. Mr. Baker said you should have that $4.50 board money.

Letter 26

Brandy Station, Virginia

April 6th 1864

Dear wife & children,

I received your letter. Was glad to hear that you was back to your home. You must write me all about your visit to the East. The money paid to Mr. Nye was just as it should be. Lt. Nye paid me $10 on that receipt & saved the risk of Lewis sending it to me by mail. I was paid on the 4th & hope you will get it soon.

I hope you got my letter. I sent 50 cents to get me a watch chain hook but I have made two axe halves & let a man have them for one he said he paid a dollar for. So you can keep the money or let either have it for the one sent back. I have not been over to the Commissary Department yet. I had it of them. If they. do not take it back, I shall have to lose it.

There is no news of importance. It has rained for the last two days & for the most part of the last 15 days—either snowed or rained, high wind, and cold. Mr. Barnard of Williamstown preached in our chapel last Sabbath p.m. He is stationed in Reserved Artillery Corps about one mile from our camp. He is a going to stop six weeks. Been some three since he came. The people in Williamstown are about the same as when you left. Uncle John Palmer has had a very bad hand & [at] one time they thought it would have to be cut off. But was better & thought they could save it. Marshall’s wife was not as well when he left.

Martin Burnham has sold his farm and going West. Mrs. Carlton is dead. She died very sudden.

I saw A. A. Earle of Irasburg Monday. He said it was very sick in that vicinity. I am glad Elthea has some taste and talent. Hope she will improve. Kiss the babies for me. In the course of three to five weeks probably we shall be on the move. Give my love to all. So goodbye for this time. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

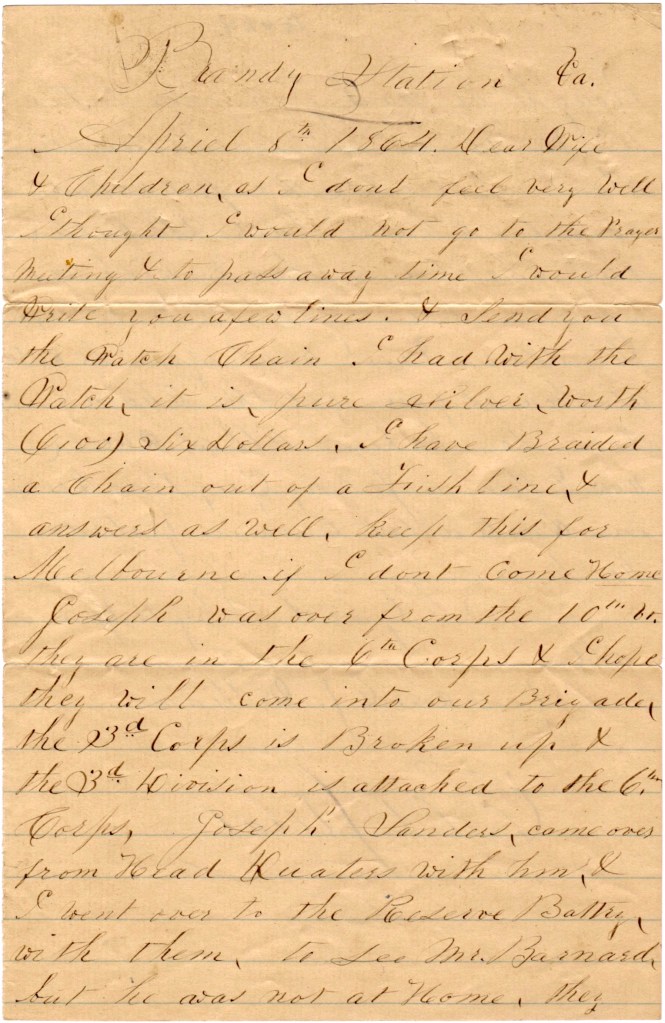

Letter 27

Brandy Station, Virginia

April 8th 1864

Dear wife & children,

I don’t feel very well. I thought I would not go to the prayer meeting & to pass away time, I would write you a few lines & send you the watch chain. I had with the watch, it is, pure silver, worth six dollars. I have braided a chain out of a fish line & answers as well. Keep this for Melbourne if I don’t come home.

Joseph was over from the 10th Vermont. They are in the 6th Corps & I hope they will come into our Brigade. The 3rd Corps is broken up & the 3rd Division is attached to the 6th Corps. Joseph Sanders came over from headquarters with him and I went over to the Reserve Battery with them to see Mr. Barnard but he was not at home. They thought he had gone over to the 10th Vermont. He starts for home in about two weeks. He preached at our chapel last Sabbath. Our chaplain is back with us again. The Rev’d A. Webster of Windsor, Vermont.

I want you to write as soon as you get this chain. Love to babies. All is quiet. Now and then a Johnny grayback comes in. Quite a lot came in yesterday. No more. So goodbye to you all. Yours ever, — E. J. Williams

Letter 28

Brandy Station, Virginia

April 29th 1864

Friend Lewis, dear sir,

As we are preparing for an active and, I hope, successful termination of this war, and as life is uncertain, would say if [my] life is not spared to return to my family, I wish both homesteads & bounty land warrants may be located & taxes paid so as to give my children the benefit of its rise, and if they should live to settle on the same. You may not be surprised if our communications, cut off from Washington for three months, we are preparing to live without Washington & not starve up in the mountains of Virginia.

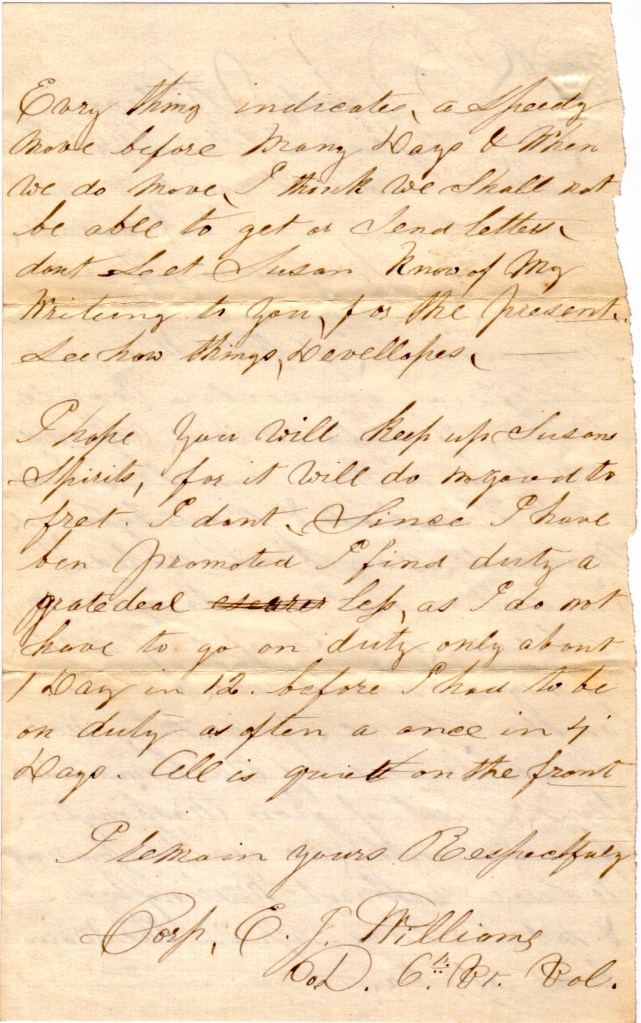

Everything indicates a speedy move before many days and when we do move, I think we shall not be able to get or send letters. Don’t let Susan know of my writing o you for the present. See how things develops.

I hope you will keep up Susan’s spirits for it will do no good to fret. I don’t. Since I have been promoted, I find duty a great deal less as I do not have to go on duty only about 1 day in 12, Before I had to be on duty as often as once in four days. All is quiet on the front. I remain yours respectfully, — Corp. E. J. Williams, Co. D, 6th Vermont Vol.