The following letters were written by James Hopkins (1839-1904), the son of William Hopkins (1805-1863) and Emma Goodwyn Hopkins (1808-1868) of Richland county, South Carolina. James attended the University of Virginia and during the Civil War served in the States Rights Guards, Co. B 1 of the 9th South Carolina Infantry and Co. K of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry. He was wounded on Oct. 22, 1862, at the Second Battle of Pocotaligo and was captured at the Battle of Matadequin Creek, Va., on May 30, 1864. He was held as a prisoner of war at Point Lookout, Md., until he was exchanged in March 1865.

Mentioned in several of the letters was English Hopkins (1842-1918), a younger brother of James. English also attended the University of Virginia and served in the same regiments as his brother, though he was not an officer.

1 Co. B—the States Rights Guards (aka the Fork Troop)—was one of the three companies of the original 2nd SC Regiment (SCV) that refused to serve in Virginia during April of 1861. The men were from the lower part of Richland District, and having remained in Charleston, SC it also helped to form the nucleus of the 9th SC Regiment (SCV). While at Ridgeville, SC in Colleton District (Dorchester County today) on June 27, 1861 the men mustered into Confederate service for twelve months, effective April 8, 1861. Duncan William Ray, MD was elected Captain in State service on April 8, 1861, and was then elected Lt. Colonel of the 9th SC Regiment (SCV) on July 12, 1861. 1st Lieutenant Robert Adams was promoted to succeed him as Captain of Company B on that same date. When the 9th SC Regiment (SCV) was disbanded in April of 1862, some of the men enlisted in Company C and 2nd Company H of the 6th SC Regiment (SCV), and two (2) men joined 2nd Company A of the 5th SC Regiment (SCV).

[Note: The following letters are from a private collection (RM) and were offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Letter 1

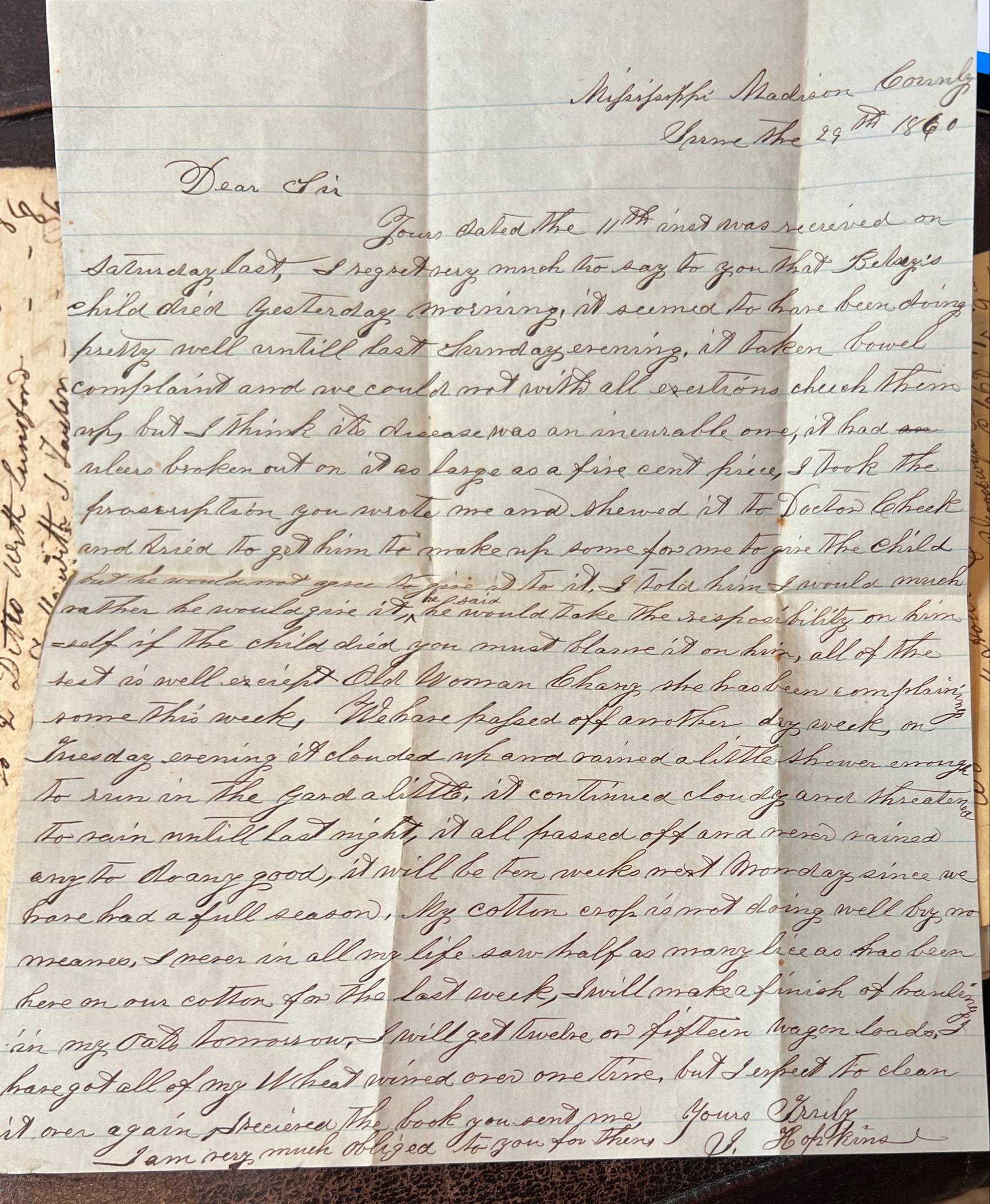

Mississippi, Madison county

June the 29th 1860

Dear Sir,

Yours dated the 11th inst. was received on Saturday last. I regret very much to say to you that Betsy’s child died yesterday morning. It seemed to have been doing pretty well until last Sunday evening. It taken bowel complaint and we could not with all exertions check them up. But I think its disease was an incurable one. It had ulcers broken out on it as large as a five cent piece. I took the prescription you wrote me and showed it to Doctor [William Alston] Cheek 1 and tried to get him to make up some for me to give the child but he wouldn’t agree to give it to it. I told him I would much rather he would give it. He said he would take the responsibility on himself if the child died. You must blame it on him. All of the rest is well except Old Woman Chany. She has been complaining some this week.

We have passed off another dry week. On Tuesday evening it clouded up and rained a little shower enough to run in the yard a little. It continued cloudy and threatened to rain until last night [when] it all passed off and never rained any to do any good. It will be ten weeks next Monday since we have had a full season. My cotton crop is not doing well by no means. I never in all my life saw half as many lice has been here on our cotton for the last week. I will make a finish of hauling in my oats tomorrow. I will get twelve or fifteen wagon loads. I have got all of my wheat wined over one time but I expect to clean it over again. I received the book you sent me. Yours truly, — J Hopkins

I am very much obliged to you for them.

1 Dr. William Alston Cheek (1825-1897) was born in North Carolina. In was enumerated in Beat 4, Madison county, Mississippi in the 1860 US Census. He died in Canton, MS, in 1897.

Letter 2

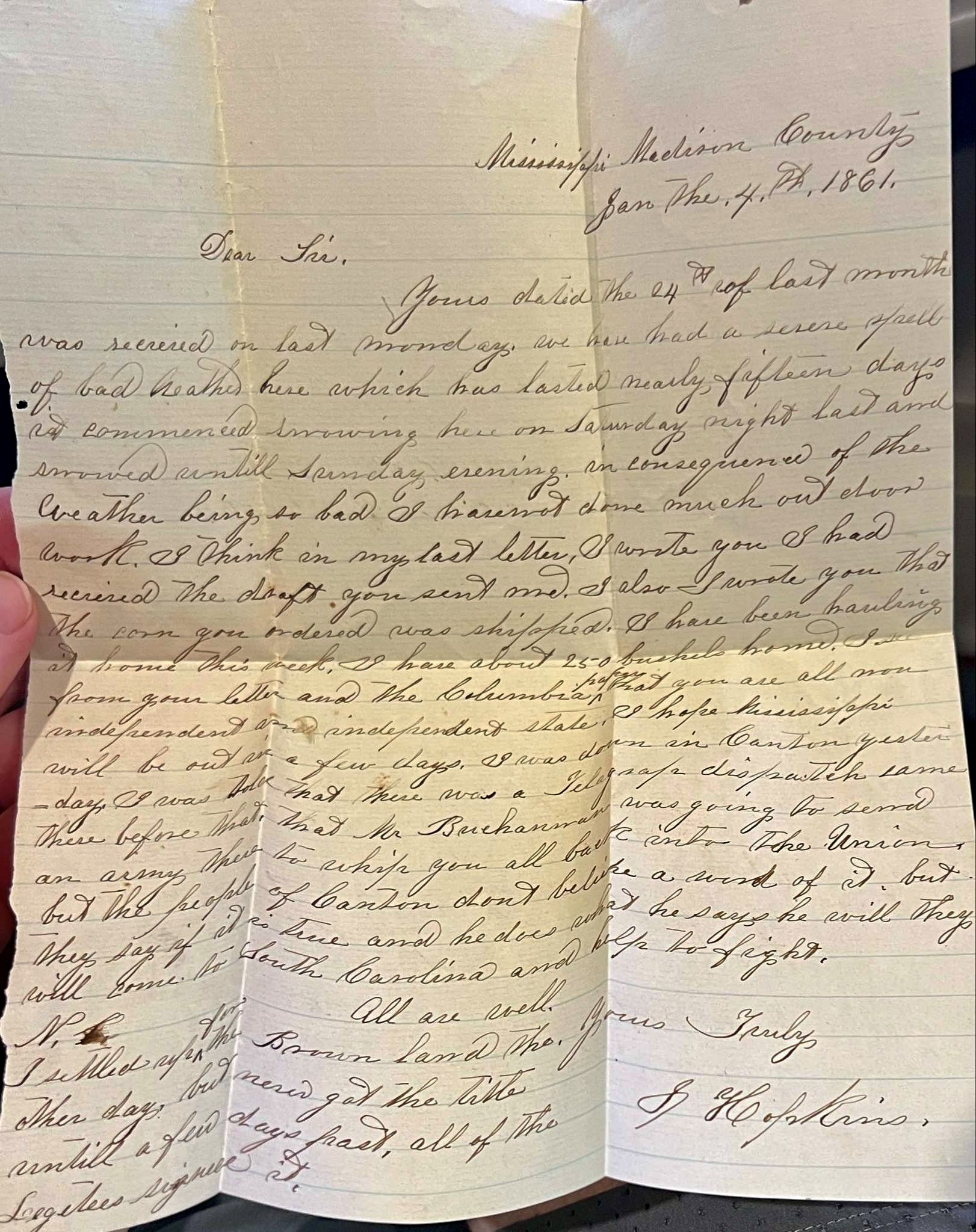

Mississippi, Madison county

January 4, 1861

Dear Sir,

Yours dated the 24th of last month was received on last Monday. We have had a severe spell of bad weather here which has lasted nearly fifteen days. It commenced snowing here on Saturday night last and snowed until Sunday evening. In consequence of the weather being so bad, I have not done much out door work. I think in my last letter I wrote you I had received the draft you sent me. I also [think] I wrote you that the corn you ordered was shipped. I have been hauling it home this week. I have about 250 bushels home.

I see from your letter and the Columbia papers that you are all now independent—an independent state. I hope Mississippi will be out in a few days. I was down in Canton yesterday. I was told that there was a telegraph dispatch [received] there before that Mr. Buchanan was going to send an army there to whip you all back into the Union but the people of Canton don’t believe a word of it. But they say if it is true and he does what he says he will, they will come to South Carolina and help to fight. All are well. Yours truly, — J. Hopkins

N. B. I settled up for the Brown land the other day but never got the title until a few days past. All of the Legatees signed it.

Letter 3

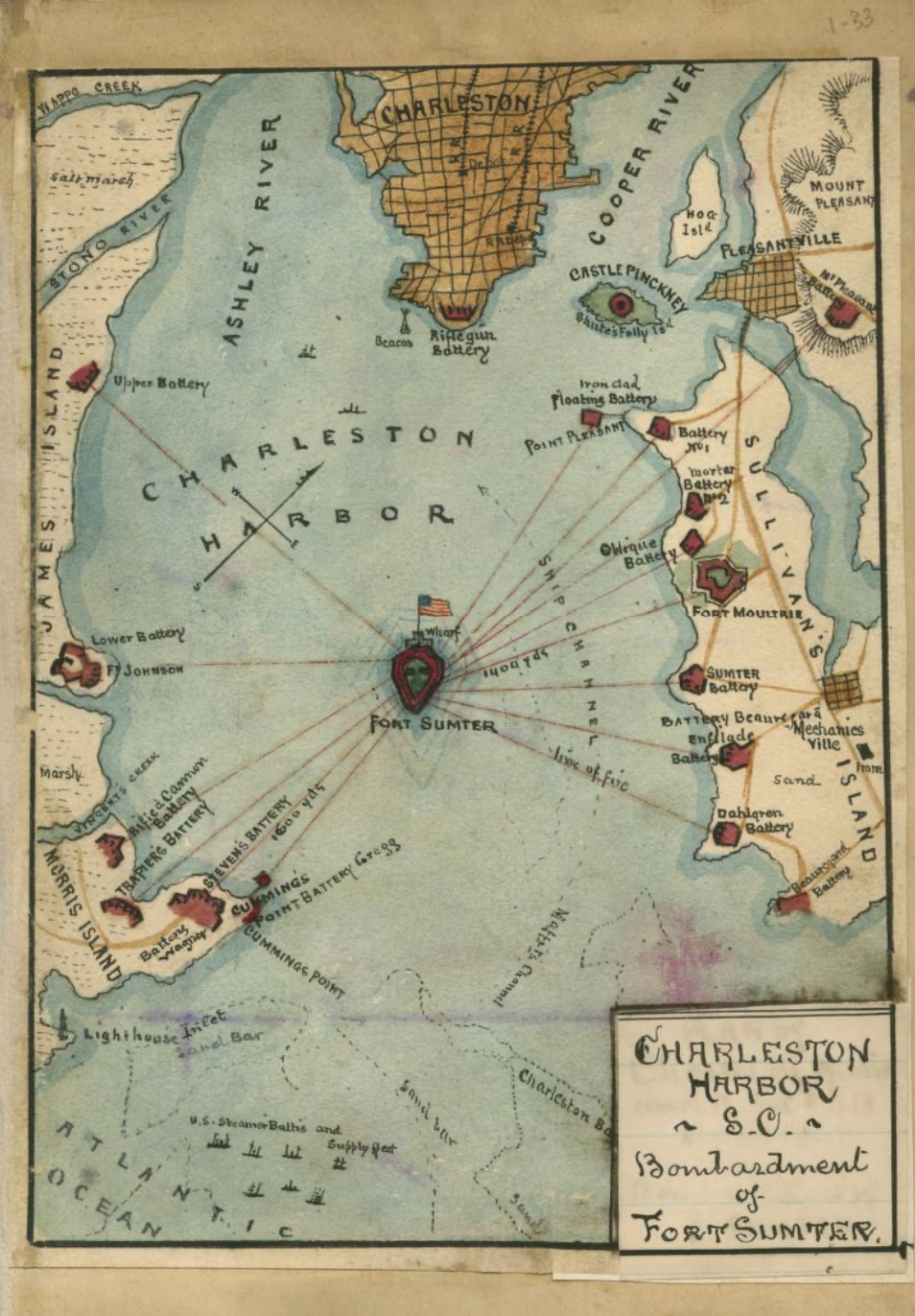

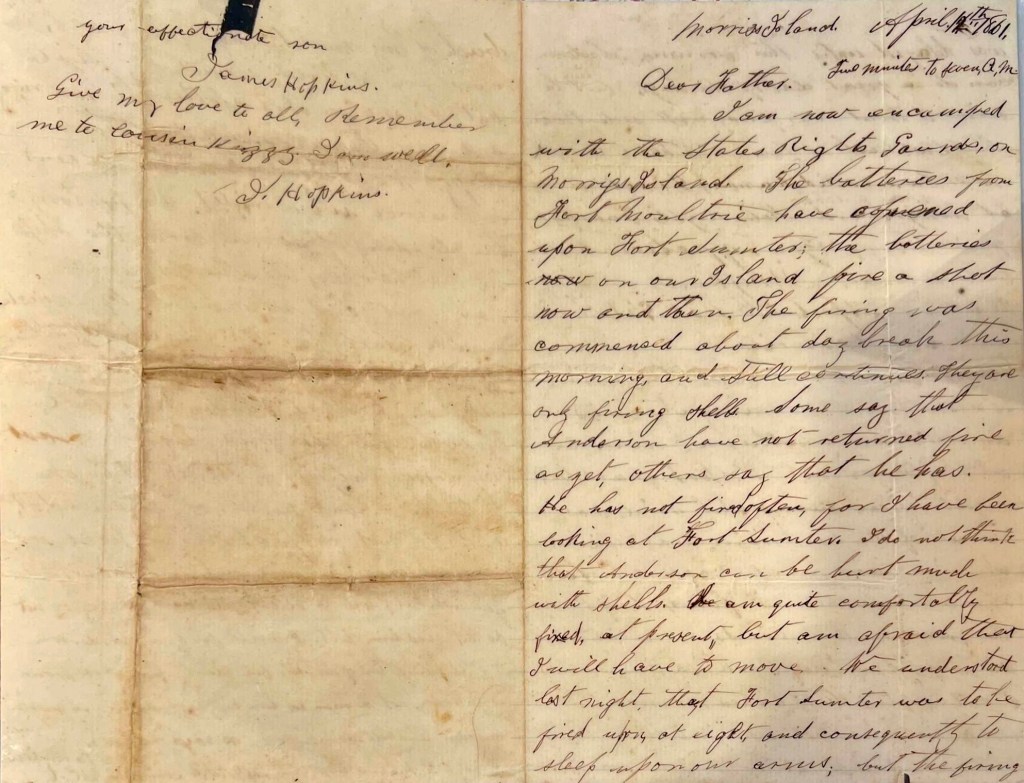

Morris Island

April 12, 1861

Five minutes to Seven a.m.

Dear Father,

I am now encamped with the States Rights Guards on Morris Island. The batteries from Fort Moultrie have opened upon Fort Sumter. The batteries on our Island for a shot now and then. The firing was commenced about daybreak this morning and still continues. They are only firing shells. Some say that Anderson have not returned fire as yet. Others say that he has. He has not fired often for I have been looking at Fort Sumter. I do not think that Anderson can be hurt much with shells. I am quite comfortably fixed, but am afraid that I will have to move. We understood last night that Fort Sumter was to be fired upon at eight and consequently to sleep upon our arms, but the firing was delayed until this morning. Anderson can do a great deal of damage but he seems to treat our firing with silent contempt—at least so far. I have to stop now. I am called to arms. Direct to me at Morris Island, States Rights Guards. — J. Hopkins (wrong direction, you will see the right directions at the end of the letter)

April 13th 1861, 9:30 a.m. o’clock. Our batteries have fired Fort Sumter. It still burns. 1 There is some talk of storming it but I do not know whether it will be attempted or not. I stood guard last night from seven until nine, was in all of the hard rain, was relieved at nine and went back at two and was relieved at four. I slept on the ground on two boards for about a half an hour before daybreak (in the open air). I only slept a half an hour during the whole night and that was just before daybreak. I slept with my head on the breach of my musket. I got very wet. Never was so tired in all my life but I have on dry clothes this morning and none the worse—only I am very sleepy.

We have been under arms ever since we arrived expecting the landing of forces from the ships in the harbor. An attempt was made but our men were too much on the alert for the Black Republicans. We will sleep on our arms tonight. Although Fort Sumter is on fire, Anderson still has his flag up.

I lost my large valise. I think it is on the Island but have not received it and do not expect to. I have not received my uniform as yet. I cannot tell you whether I will be allowed to have a boy or not. Do not send him till I write for him. Anderson is still firing. One of his balls fell about fifty yards from us yesterday. Not a man has been killed by Anderson. A mortar bursted and kill[ed] twenty men, so says rumor.

Direct to James Hopkins, Capt. [Duncan William] Ray’s Company, 2 S. C. Volunteers, Charleston

Your affectionate son, — James Hopkins

Give my love to all. Remember me to Cousin Kizzy. I am well. — J. Hopkins

1 Most reports of the bombardment claim that a dense volume of smoke was seen suddenly to arise from Fort Sumter following at explosion around 9 o’clock a.m. of April 13th 1861.

2 Duncan William Ray, MD, (1812-1868), of Richland District, was Captain of the States Rights Guards in the original 2nd SC Regiment (SCV) that refused to march to Virginia. This Company became Company B—the Fork Troop—in this, the 9th SC Regiment (SCV). During the second election of Field Officers on July 12, 1861, he was elected Lt. Colonel of the 9th SC Regiment (SCV) in lieu of Dixon Barnes (above) who had been elected on July 5th. Dr. Duncan William Ray graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and was a well-known physician and planter in Lower Richland County, South Carolina.

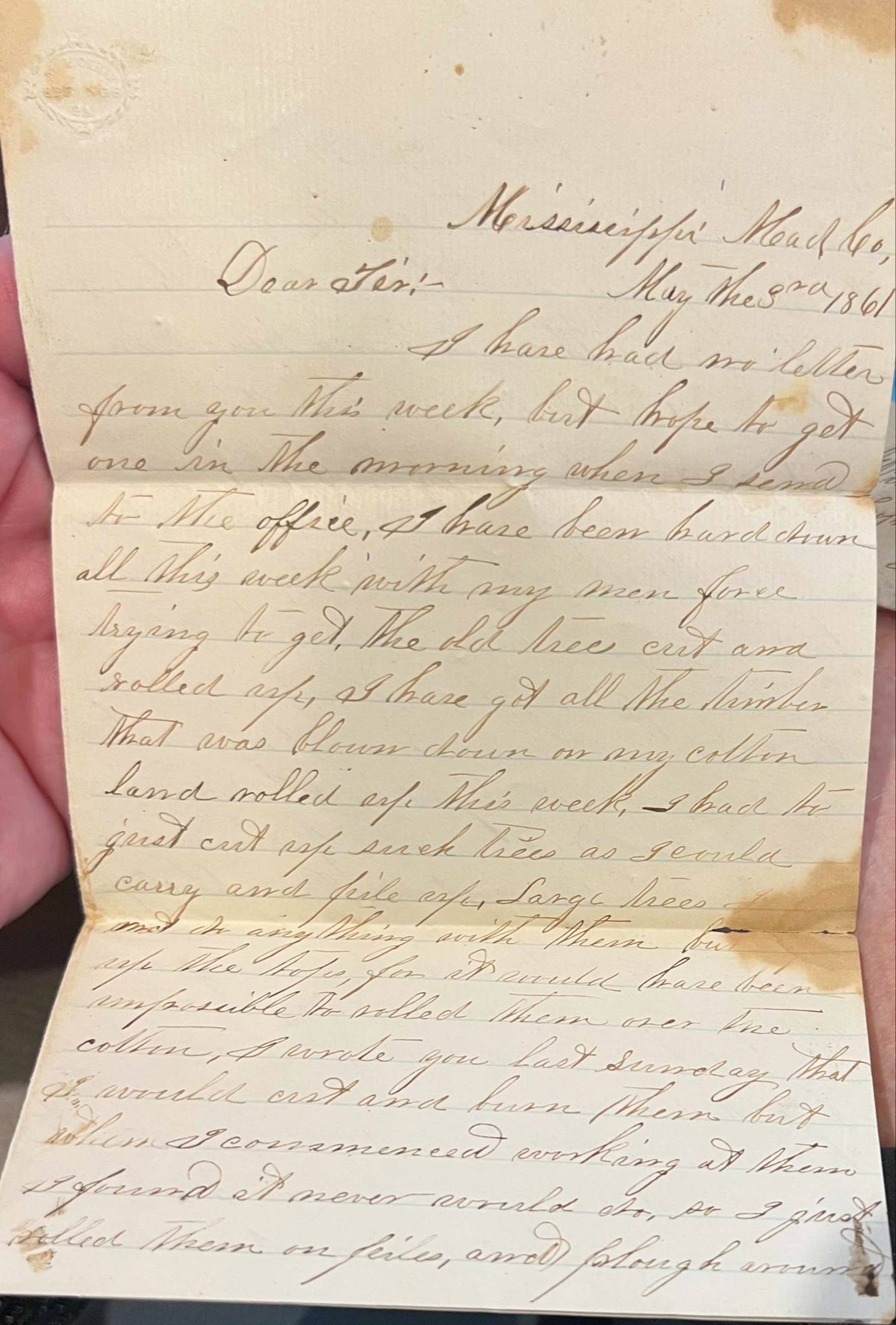

Letter 4

Mississippi, Mad[ison] County

May the 3rd, 1861

Dear Sir,

I have had no letter from you this week but hope to get one in the morning when I send to the office. I have been hard down all this week with my men force trying to get the old trees cut and rolled up. I have got all the timber that was blown down on my cotton land rolled up this week. I had to just cut up such trees as I could carry and pile up. Large trees I cannot do anything with them but cut up the tops for it would have been impossible to rolled them over the cotton. I wrote you last Sunday that I would cut and burn them but when I commenced working at them I found it never would do, so I just rolled them on piles and plough around them the best I could. It will take me another week with my men to get the timber piled so I can do anything with them. There is some places in the land that I cleared last winter that I cannot do anything with in consequence of so much timber being on it.

We have had more heavy rain here this year tham I ever witnessed in the spring. On Monday evening last it commenced raining and continued all night as hard as ever you heard it I recon. Yesterday we had another wet day. Our swamp has been flooded up this week so that I could do nothing but roll up logs this week. I see my cotton has not come up as well as I would like but that is very easy accounted for nothing like corn or cotton could come up with the rain that has fallen here for the last four weeks. I don’t see how I am to save my wheat & oats and take care of my corn and cotton, losing so much time now. [It] will throw me late in getting my crop worked over. But rest assured, I will do all I can to save both. I see my wheat has got the rust in it. But I only noticed it on the blades. I don’t see any on the stalk yet. I have been searching my oats to see if it had attacked them but didn’t discover any. There is a good deal of complaint in the country of the oats and wheat having the rust. I have ploughed around 160 acres of corn this week. I couldn’t get [ ] tomorrow but will finish on Monday.

I see that Old Abe has declared war and nothing else will do him but it. There was 1200 Louisiana troops passed through Canton last Tuesday for Virginia. All are well.

Yours truly, — J. Hopkins

Letter 5

[Editor’s Note: From September 14-20, 1861, the 9th SC Regiment (SCV) performed picket duty, which included light picket firing. Circa September 25th, the Regiment was again on picket duty for three (3) days near Lewinsville, then again October 5-9 at Wells Cross Roads, both in Virginia. On October 16th, the Regiment left Germantown for McLean’s Ford, VA and was engaged in picket firing the next day near the Makeley House, where it mistakenly fired on a Georgia regiment. The 9th SC Regiment (SCV) took one or two (1 or 2) prisoners only to discover they were Georgians.]

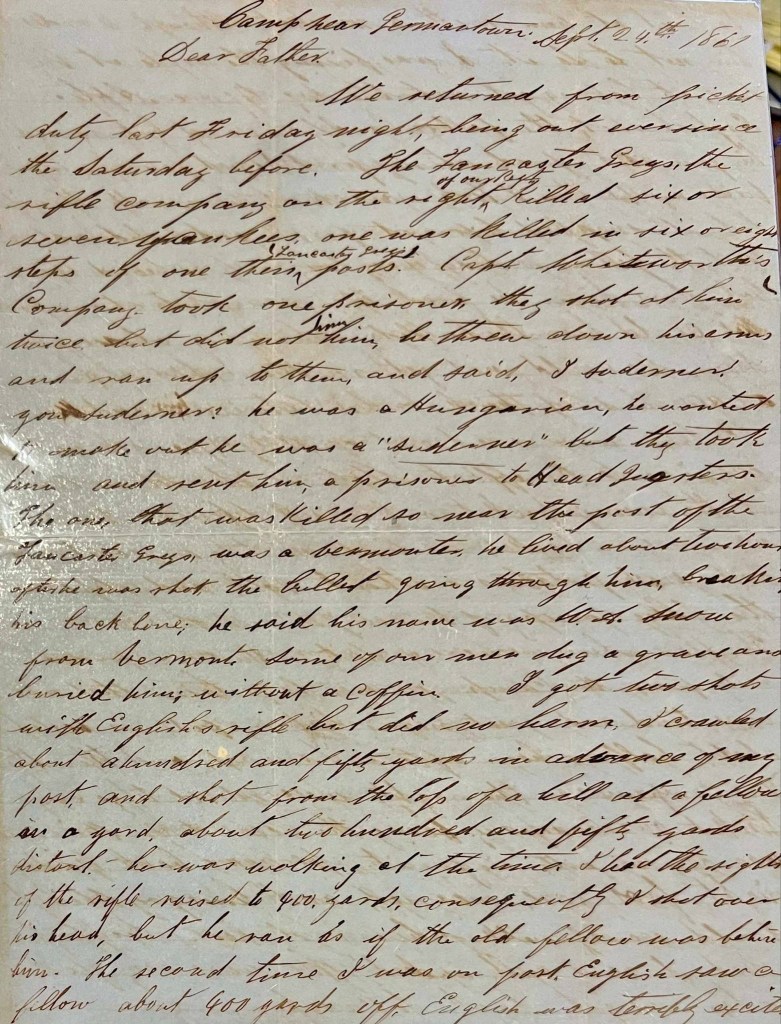

Camp near Germantown [Fairfax county, Va.]

September 24th 1861

Dear Father,

We returned from picket duty last Friday night, being out ever since the Saturday before [Sept. 14-20]. The Lancaster Greys [Co. A], the rifle company on the right of our regiment, killed six or seven Yankees. One was killed in six or eight steps of one of their (Lancaster Greys) posts. Capt. Whitworth’s Company [Co. C] took one prisoner. They shot at him twice but did not hit him. He threw down his arms and ran up to them and said, “I Suderner, you Suderner.” He was a Hungarian. He wanted to make out he was a “suderner” but they took him and sent him a prisoner to Headquarters. The one that was killed so near the post of the Lancaster Greys was a Vermonter. He lived about two hours after he was shot, the bullet going through him, breaking his backbone. He said his name was W. A. Snow 1 from Vermont. Some of our men dug a grave and buried him without a coffin.

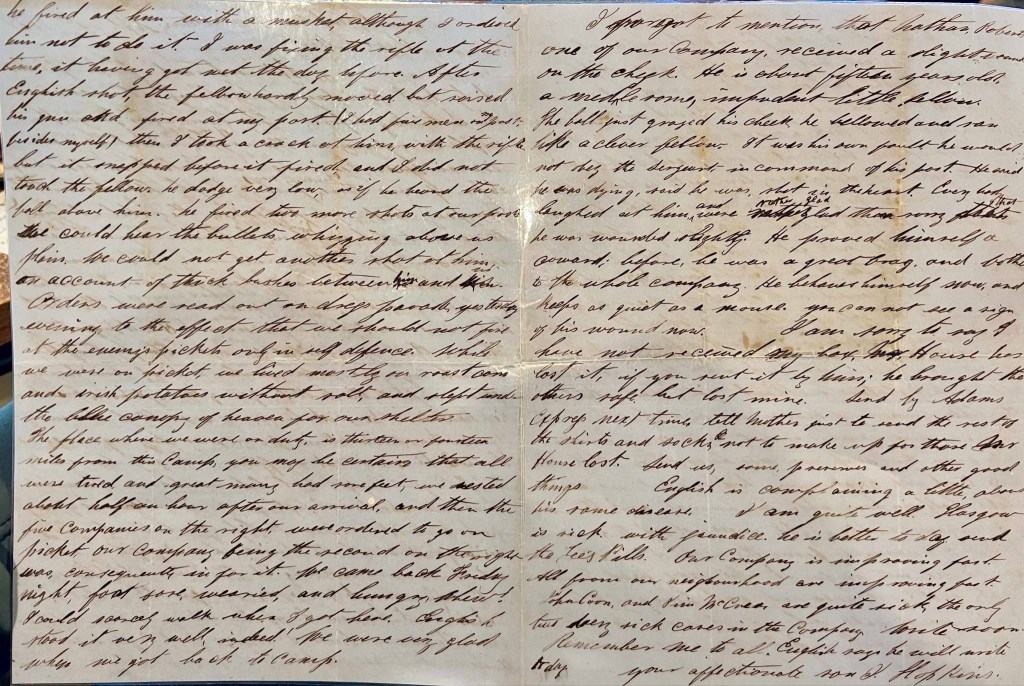

I got two shots with English’s rifle but did no harm. I crawled about a hundred and fifty yards in advance of my post and shot from the top of a hill at a fellow in a yard about two hundred and fifty yards distant. He was walking at the time. I had the sights of the rifle raised to 400 yards. Consequently, I shot over his head but he ran as if the old fellow was behind him. The second time I was on post. English saw a fellow about 400 yards off. English was terribly excited. He fired at him with a musket although I ordered him not to do it. I was fixing up the rifle at the time, it having got wet the day before. After English shot, the fellow hardly moved but raised his gun and fired at my post (I had five men at my post besides myself). Then I took a crack at him with the rifle but it snapped before it fired and I did not touch the fellow. He dodged very low as if he heard the ball above him. He fired two more shots at out post. We could hear the bullets whizzing above us plain. We could not get another shot at him on account of thick bushes between him and us.

Orders were read out on dress parade yesterday evening to the effect that we should not fire at the enemy’s pickets—only in self defense. While we were on picket, we lived mostly on roast corn and Irish potatoes without salt, and slept under the blue canopy of heaven for our shelter. The place where we were on duty is thirteen or fourteen miles from this camp. You may be certain that all were tired and a great many had sore feet. We rested about half an hour after our arrival and then the five companies on the right were ordered to go on picket, our company being the second on the right was, consequently, in for it. We came back Friday night, foot sore, wearied, and hungry sure! I could scarcely walk when I got here. English stood it very well indeed! We were very glad when we got back to camp.

I forgot to mention that Nathan Roberts, one of our company, received a slight wound on the cheek. He is about fifteen years old—a meddlesome, impudent little fellow. The ball just grazed his cheek. He bellowed and ran like a clever fellow. It was his own fault. He would not obey the sergeant in command of his post. He said he was dying, said he was shot in the heart. Everybody had laughed at him and were rather glad than sorry that he was wounded slightly. He proved himself a coward. Before he was a great brag and bother to the whole company. He behaves himself now and keeps as quiet as a mouse. You cannot see a sign of his wound now.

I am sorry to say I have not received my box. Mr. House has lost it if you sent it by him; he brought the others safe but lost mine. Send by Adams Express next time. Tell Mother just to send the rest of the shirts and socks & not to make up for those Mr. House lost. Send us some preserves and other good things. English is complaining a little about his same disease. I am quite well. Hasgow is sick with jaundice. He is better today. Send to Lee’s Pills. Our company is improving fast. All from our neighborhood are improving fast. John Coon and Jim McCrea are quite sick, the only sick cases in the company. Write soon. Remember me to all. English says he will write today. Your affectionate son, — J. Hopkins

1 James remembered his name as “W. A. Snow” but it was surely William E. Snow (1841-1861) of Co. H, 2nd Vermont Infantry. Only the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Vermont regiments had been formed and deployed to Virginia by September 1861 and William was the only private in any of these three regiments whose first name started with a “W.” His military records indicate he was “wounded” while on picket and taken POW. He was officially removed from the muster rolls on 30 September 1861. William was the son of Lewis and Hannah (Shaw) Snow of Milton, Chittenden county, Vermont.

Letter 6

Camp of CSA

June 15, 1863

Dear Mother,

Your letter was received last week. I hope sister is not seriously ill. I will excuse her for not writing to me but hope to hear from her soon. I wrote to Father yesterday and to Sallie today.

Jack Bates came to camp Friday last and returned yesterday. He was looking very bad indeed. He intends to put in a substitute. I think he is perfectly right for he is not able to stand the service. If he continues in service another year, I believe it will kill him. He did not bring the wine. He will bring it this week. He expects to bring his substitute down tomorrow or next day.

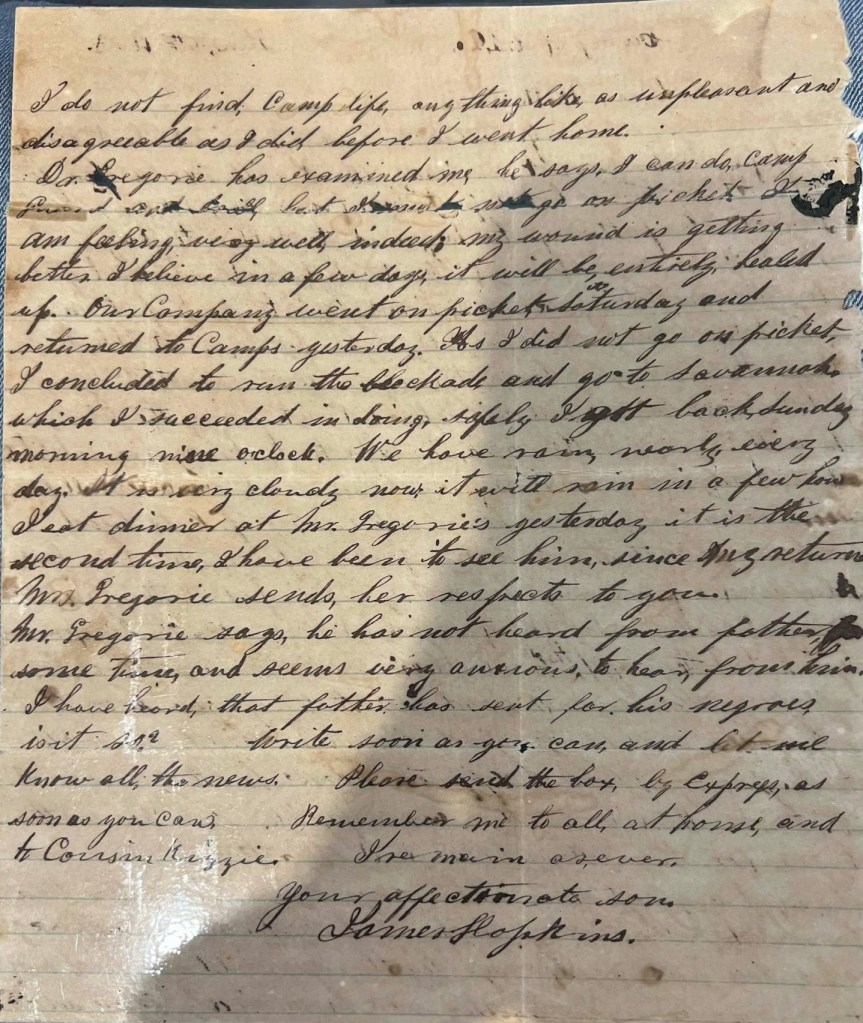

Please send me a small box with some ginger and pound cakes, a loaf of light bread, a can of butter, and about a peck of flour. We have lard. Also send a few cucumbers and squashes. Put the things in as small a box as possible. If no one at home eats the fig preserves, you had better send them to me. Please make me a bottle or two of cherry bonnce [?] and send me—that is, if you have the cherries. I left the pad that goes behind my saddle to keep my blanket off the horse’s back. Please send it to me. Have as small a box as possible. Bob has written home for two or three hams and other things. Bob has changed a great deal in his ways. I like him better than I ever did. He is very much liked by the whole company. Bob, Joel, and myself mess together. you could not find any three men who agree together more harmoniously than we do. I do not find camp life anything like as unpleasant and disagreeable as I did before I went home.

Dr. Gregorie has examined me. He says I can do camp guard and drill but I must not go on picket. I am feeling very well indeed. My wound is getting better. I believe in a few days it will be entirely healed up. Our company went on picket Saturday and returned to camp yesterday. I did not go on picket. I concluded to run the blockade and go to Savannah which I suceeded in doing safely. I got back Sunday morning nine o’clock.

We have rain nearly every day. It is very cloudy now. It will rain in few hours. I eat dinner at Mr. Gregorie’s yesterday. It is the second time I have been to see him since my return. Mrs. Gregorie sends her respects to you. Mr. Gregorie says he has not heard from father for some time and seems very anxious to hear from him. I have heard that Father has sent for his negroes. Is it so? Write soon as you can and let e know all the news. Please send the box by Express as soon as you can. Remember me to all at home and to Cousin Kizzie. I remain as ever, your affectionate son, — James Hopkins