The following letter was written by 1st Sergeant Daniel H. Schriver (1836-1864) of Co. I, 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. He enlisted in September 1861 and was promoted from 1st Sergeant to 2nd Lieutenant on 8 November 1863. He was killed in a brisk skirmish at Flat Creek Bridge, Virginia, on 14 May 1864. At the time of his enlistment, Daniel was described as a 25 year-old, 5′ 4″ tall, black-haired saddler.

Schriver’s letter informs his brother of the evacuation from White House Landing, McClellan’s Supply Depot on the Pamunkey river in June 1862 when J. E. B. Stuart conducted his raid. He referred to him as Jackson but it was actually Stuart.

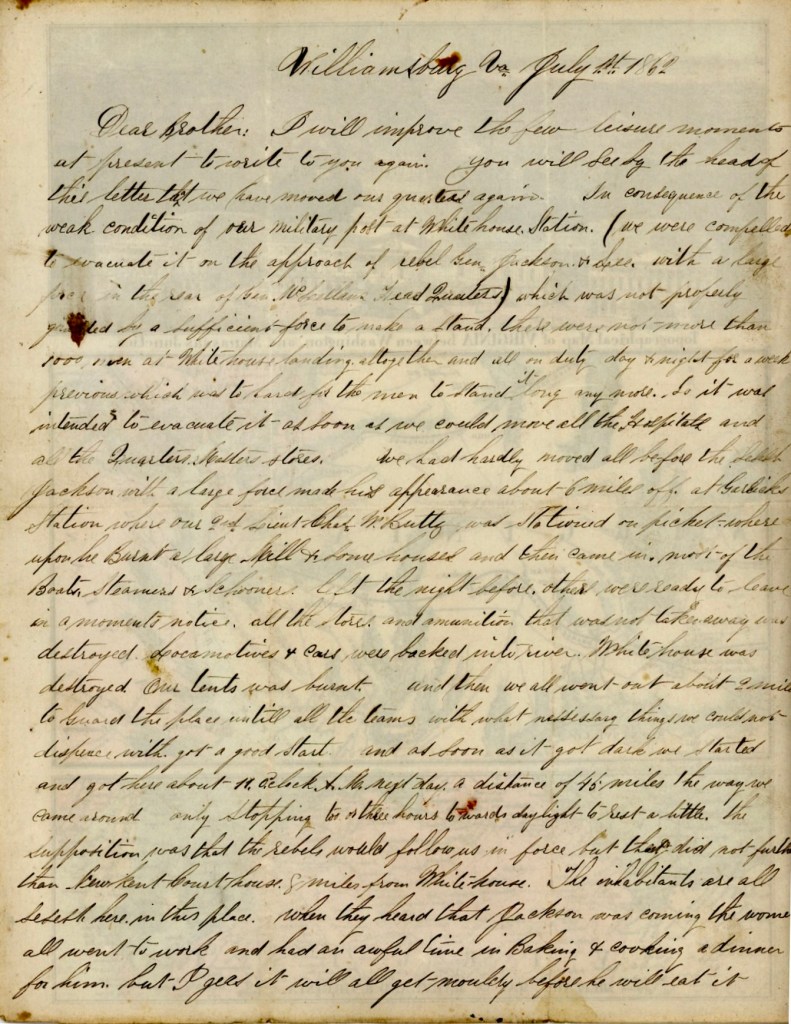

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Williamsburg, Va.

July 1st 1862

Dear Brother,

I will improve the few leisure moments at present to write to you again. You will see by the head of this letter that we have moved our quarters again. In consequence of the weak condition of our military post at White House Station, we were compelled to evacuate it on the approach of Gen. Jackson & Lee with a large force in the rear of McClellan’s Headquarters which was not properly guarded by a sufficient force to make a stand. There were not more than 1,000 men at White House Landing altogether and all on duty day and night for a week previous which was too hard for the men to stand it lone anymore. So it was intended to evacuate it as soon as we could move all the hospital and all the quartermaster’s stores.

We had hardly moved all before the Secesh Jackson with a large force made his appearance about 6 miles off at Garlick’s Station where our 2nd Lieutenant Chas. W. Butts was stationed on picket whereupon he burnt a large mill & some houses and then came in. Most of the boats and schooners left the night before; others were ready to leave in a moment’s notice. All the stores and ammunition that was not taken away was destroyed, locomotives and cars were backed into river. 1 White House was destroyed. Our tents was burnt. And then we all went out about two miles to guard the place until the teams with what necessary things we could not dispense with got a good start, and as soon as it got dark, we started and got here about 11 o’clock a.m. next day—a distance of 45 miles the way we came around, only stopping two r three hours towards daylight to rest a little.

The supposition was that the rebels would follow us in force but they did not further than New Kent Court House, 8 miles from White House. The inhabitants are all secesh here in this place. When they heard that Jackson was coming, the women all went to work and had an awful time in baking and cooking a dinner for him but I guess it will all get moldy before he will eat it.

I do not think we will stay here long but where we will go to next I cannot say. But I hope not to a place where there are too few troops and so much duty to do. There sounds the bugle for sick call. I must go and see if anybody is sick enough to go to the Doctor’s 9in order to shirk duty). Excuse this scratching. I have to do it all on my knee under two India rubber blankets for tents. Yours expecting a letter soon from you, I remain your devoted brother, — Dan’l H. Schriver, 1st Sergt. Co. I

The surest way to direct your letters since we have no permanent encampment is to Camp Hamilton, Fort Monroe, Va., or to Washington D. C. and the other preliminaries and it will follow.

P. S. Enclosed you will find part of a Magnolia flower that grows wild here on pretty large trees.

1 J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry raided Garlick’s Landing on the Pamunkey River above the railroad bridge and captured 14 wagons and some sutler’s stores, and burnt two schooners laden with forage and then headed toward Tunstall’s Station.

War Correspondent George Alfred Townsend was heading back to White House at the time of Stuart’s raid and described what he saw at Garlick’s Landing and White House when he arrived: “I remained a full hour under cover; but as no fresh approaches added to my mystery and fear, I sallied forth, and kept the route to Putney’s, with ears erect and expectant pulses. I had gone but a quarter of a mile, when I discerned, through the gathering gloom, a black, misshapen object, standing in the middle of the road. As it seemed motionless, I ventured closer, when the thing resolved to a sutler’s wagon, charred and broken, and still smoking from the incendiaries’ torch. Further on, more or these burned wagons littered the way, and in one place two slain horses marked the roadside. When I emerged upon the Hanover road, sounds of shrieks and shot issued from the landing a “Garlic,” and, in a moment, flames rose from the woody shores and reddened the evening. I knew by the gliding blaze that vessels had been fired and set adrift, and from my place could see the devouring element climbing rope and shroud. In a twinkling, a second light appeared behind the woods to my right, and the intelligence dawned upon me that the cars and houses at Tunstall’s Station had been burned. By the fitful illumination, I rode tremulously to the old head-quarters at Black Creek, and as I conjectured, the depot and train were luridly consuming. The vicinity was marked by wrecked sutler’s stores, the embers of wagons, and toppled steeds. Below Black Creek the ruin did not extend: but when I came to White House the greatest confusion existed. Sutlers were taking down their booths, transports were slipping their cables, steamers moving down the stream. Stuart had made the circuit of the Grand Army to show Lee where the infantry could follow.”

Joel Cook described what he heard about the attack on the train passing through Tunstall’s Station and the reaction at White House Landing: “There were numerous passengers on the cars, mostly laborers, civilians, and sick and wounded soldiers, and a general effort was made to jump off, and, if possible, elude the enemy’s fire. Several succeeded, and hid themselves in the wood; but the quickly increasing speed of the train prevented the majority from following their example. The cars, however, were soon out of reach of the Rebels, and the engineer, fearful of pursuit or of meeting more enemies, increased the pressure of steam so that the train almost flew over the distance between Tunstall’s Station and White House. There the news of what had occurred spread like lightning, and there was the utmost consternation among the sutlers, civilians, clerks, laborers, and negroes who inhabited the canvas town which had sprung up on the Pamunky. Lieutenant-colonel Ingalls, of the quartermaster’s department, was the officer in command, and, under fear of impending danger, he mustered the few soldiers who were at the place, and armed the civilians and laborers. He also placed all the money, records, mails, and other valuable property of the United States upon a steamboat in the river. The panic among the sutlers was beyond all description: each one expected utter ruin, and awaited, with an anxious heart, the approach of the enemy. They did not come, however, and White House, though it was so soon to be destroyed, had a short respite.” [Source: White House Landing Sustaining the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign.]