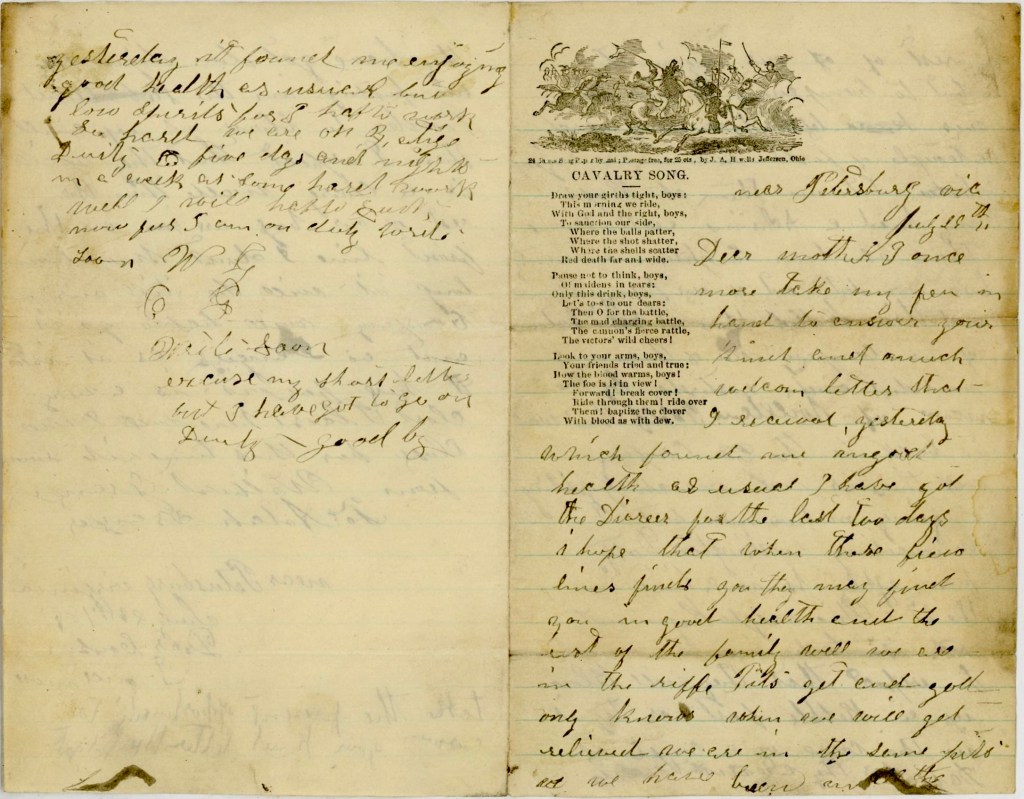

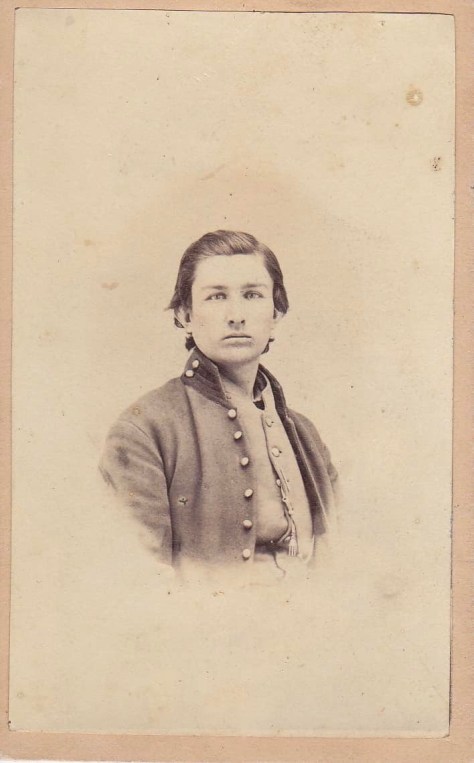

The following letter was written by Wilbert Granger (1845-1904), the son of Dr. George Granger of Westfield, Morrow county, Ohio. Wilbert enlisted initially in Co. B, Fifth Independent Battalion, Ohio Volunteer. Cavalry (OVC) and then reenlisted 5 May 1864 in Co. B of the 13th OVC when the 4th and 5th Cavalry Battalions were consolidated. The regiment left Ohio for Annapolis, Md., in May and then moved to White House Landing, Va. where they soon joined Grant’s Overland Campaign. According to his obituary, Wilbert “participated in all the battles in which his regiment was engaged. In one battle he received an injury which resulted in partial deafness and at the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House he received a wound in his left shoulder” that troubled him the remainder of his life. He was married in 1867 to Mary A. Olds and lived out his days in Olathe, Kansas.

Gilbert wrote this letter on 29 July 1864, the day before the mine explosion that initiated the Battle of the Crater in which the 13th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry were only partially involved. See footnote 2.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Near Petersburg, Va.

July 29th [1864]

Dear mother,

I once more take my pen in hand to answer your kind and much welcome letter that I received yesterday which found me in good health as usual. I have got the diarrhea for the last two days. I hope that when these few lines find you, they may find you in good health and the rest of the family well.

We are in the rifle pits yet and God only knows when we will get relieved. We are in the same pits as we have been and all the rest of our regiment but two companies—B and H—was left here to guard a couple of forts here. We are laying between them. It keeps my head aching all the time.

There has been eighteen or twenty been wounded out of our regiment and three killed. There is three out of our company. One of them was wounded yesterday by the name of William Wolf. Bill Ward is back to the company.

Well, there is not much fighting a going on here now but I have been visiting [George] Washington Doty from Ashley. He is a [1st] Lieutenant in [Co. G of] the 27th Ohio Negro Regiment and is back in the woods. 1 I expect that they will blow up a Rebel fort or try it in the course of a couple of days for they are most ready. They have got done digging. They are putting in the powder to blow it up. Then I expect that there will be a charge made then.

The rest of our boys are on the front line. I don’t know how long it will be till our company will have to go it and as dangerous as it is, I have forgot it is a very close place here. Well I now close for this time. Write soon. From Wilbert Granger

To Adah Granger

Near Petersburg, Virginia,

July 28th, 1864

Dear cousin, I once more take the present opportunity to answer your kind letter that I got yesterday. It fond me enjoying good health as usual but low spirits for I have to work so hard. We are on fatigue duty for five days and nights in a week at some hard work. Well, I will have to quit now for I am on duty. Write soon. — W. G.

Excuse my short letter but I have to go on duty. Goodbye.

1 The 27th USCT was the second black regiment organized in Ohio. The state government of Ohio was slow to organize black regiments and the first African Americans from the state to join the Union army from Ohio were those who enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts in the early months of 1863. The 27th was not organized until January of 1864. It participated in the Overland Campaign guard supply trains and did not experience its first real combat until the Battle of the Crater. Because it was one of the last Black regiments to enter the battle, it did not suffer as many casualties as the other Black regiments.

2 The 13th OVC and the Battle of the Crater: “Through July 29, 1864 the men of the 13th Ohio would be engaged in direct, position to position line fire. Most of the wounds received would be to men who were unlucky enough to break their cover, and a good number of the dead were the result of disease. The harshness of the campaign would take a visible toll on the men, their appearance from when they first moved out on the march until now differs substantially. They are now dirty, their clothes are ragged and torn, hair is a mess, and to make matters worse most of the food was bad. Their hardtack was infested with bugs, a problem that was solved simply by dipping it in hot coffee, forcing the bugs out. Their meat had turned rancid and the water used for drinking and cooking was gathered from contaminated sources from the battling raging around them, yet the men would still report that they were generally a jolly set of men. Most of the men had not washed their shirts in over a month at this point.

Sometime during July 29, 1864, the men received orders to leave their positions and return to the rear. A chance would finally be granted for them to clean up, and they received word that The Christian Commision had sent them a large shipment of canned fruit, red herring, tobacco and bandages. Around 2 a.m., on Saturday July 30,1864, the men would hear the troops that they thought were coming to relieve them approaching. When the men of the 13th Ohio could see them, to their surprise, they were equipped with bayonets fixed on their rifles. The boys of the 13th Ohio asked, “What’s up?” And they were met with the reply of “Don’t know, but guess we’re going to make a charge. The 13th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry Regiment poured out of their breast works, formed a column, and moved to a depression in the bluff towards an open space that sloped and ran up to the breast works. Here in the predawn darkness, the boys could see a large body of troops from other Union units, they now knew for sure they were to make an assault.

During the time the boy of the 13th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry Regiment manned their positions across from Elliots Sailent, Colonel Pleassants and of his men (the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, composed mostly of men who had worked in the coal mines), had done what they knew best. They dug a tunnel that reached all the way under the confederates position, they excavated two or three rooms at the end of the tunnel and rolled barrels, totaling approximately 8,000 pounds of black powder, into said rooms and ran a fuse back to the mouth of the makeshift mine. Colonel Pleassants would light the fuse at approximately 3:15 a.m. but due to a malfunction at the fuse splice approximately halfway through the tunnel, he would have to crawl back in and relight it from that point. It would finally go off right after sunrise, the ground could be felt rumbling as dirt, dust, smoke and a 200 foot fireball could be seen coming from Elliott’s Salient.

Leslie’s First Division was to spearhead the attack. Meanwhile Potter’s Second Division (on the right side), and Willcox’s 13th Ohio (on the left side) followed directly behind. The men watched as the explosion blew Confederate soldiers into the air, and in some cases to pieces. Due to a last minute change of personnel, prior the attack, it was approximately a full ten minutes before the assault commenced, but the surrounding forts opened up every gun aimed at the Rebel positions immediately. The 13th Ohio Boys watched as cannon balls and other heavy ammunition bounced off the ground and through the enemy. During this the Union men receive the order to move forward over their breast works. They fought through all of the carnage going on in the air until they were forced to lay down in a covered position approximately halfway between their original positions to the “crater”.

After the firing let up just a little bit the Union men were able to advance on the crater. What they found were horrors they could not imagine. The bodies of horses, wreckage of gun carriages and half bodied rebels, some still alive and begging for help, littered the ground. The crater, which was no more than the result of the black powder explosion the Union Army let off, was a hole approximately 150 feet long, 60 feet wide and 30 to 40 feet deep.

As it took more time than originally thought, by the time the assault force of The Union Army reached the lip of the crater, the surviving Confederates soldiers had a few minutes to compose themselves and line up along their top ridge of the crater. As the Union soldiers (approximately 2,000) entered the crater, the Rebels had a turkey shoot, picking off the men who were piled up in the confusion inside of the hole, as well as directing artillery directly into the crater. A large group of approximately 300 Union Army troops stood at the base of the edge, staring up at the Rebels, and firing to hopefully help defend their comrades towards the opposite end of the crater.

Some small groups that were able to escape the crater and flank to the right engaged the Rebels directly at their lines. Engaging in very close hand to hand fighting, the Union troops drove the Rebels back for several hours until another group of rebels reinforced their men and drove the Union Soldiers back to the East for good.

The battle would rage on until approximately 3 p.m. on August 1, 1864, when the men reached a ceasefire. It would be a technical Confederate win, resulting in 3,798 Union Casualties. 1,413 were missing or captured, 1,881 would be wounded and 504 would be killed. Sometime during this carnage of “The Battle of The Crater”, Daniel Kester would receive a bullet wound to his left shoulder in which he would later succumb to, most likely due to blood loss. Many of the men of the 13th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry Regiment could be identified only by their distinctive cavalry jackets.

It is not known with 100% certainty where the mortal remains of Daniel Kester are buried. Due to the lack of a publicly recorded grave site, it is believed that he is buried in the Civil War Unknowns Memorial, located in Arlington National Cemetery, along remains of over 2,100 other soldiers who were not able to be identified after the hostilities of The Civil War ended.” [Source: Mid Ohio Military Collection: A Traveling Museum Exhibit’s Post]