The following letter was written by Felix J. Williams (1844-1863), the second son of eight children born to Henry John and Mary (Weaver) Williams of Elk Creek, Alleghany County, North Carolina. Felix enlisted in Co. K, 37th North Carolina Infantry on 15 August 1862. He joined his regiment near Martinsburg in the Army of Northern Virginia on 26 September. This letter, from a private collection, was written shortly after his arrival.

Twenty letters authored by Felix, acquired in 1995, are preserved within the North Carolina Digital Collections. These correspondences were predominantly directed to his entire family, although select letters were intended specifically for his mother or father. For a duration of two months, Williams endured the rigors of camp life and arduous marches. In late October, he and his regiment were assigned the task of dismantling the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad between Hedgesville and North Mountain Depot in West Virginia, and on December 13, 1862, Williams encountered the harsh realities of warfare at Fredericksburg.

After the battle, the regiment took up winter quarters in Camp Gregg at Moss Neck, positioned on the Rappahannock River approximately eight miles downstream from Fredericksburg. Here, Williams and the regiment endured the harsh conditions until the commencement of the 1863 campaign at the close of April. On 1 May 1863, the regiment advanced towards Chancellorsville. On May 3, during a fierce engagement, Jackson’s corps, commanded by Gen. Stuart, repelled Hooper and the federal forces, resulting in severe casualties for the 37th Regiment—19 officers were wounded and 1 was killed; among the ranks, 175 men were wounded and 35 were killed—-including 19 year-old Felix J. Williams.

“Though not from a wealthy family, Williams had come from a prosperous and self sufficient one. He and his father had raised grains and hay on the family farm of 100 acres of cleared land and 250 acres of woodland. The farm had also produced wool, butter, honey, nuts, and fruits for the family. The young soldier’s letters hearken back to apples, dried peaches, chinkapins, eggs, and other good things at home when he writes from his comfortable but hungry winter quarters at Camp Gregg. He reports the visit of his father and grandfather with boxes of food just at the time that soldiers convicted of desertion are being shot in the camp (letters of Feb. 23 and 28, 1863). A subsequent letter (March 8) mentions two desertions from the regiment and assures his family that he’d never desert—“I will come out of this war like a man or I will die in it.” Other letters refer to the issue of Austrian rifles to replace his company’s old muskets (Feb. 18, 1863), contain reflections on his captain as a company commander (Mar. 19, 1863), and speak of sickness and religion in the camp (Apr. 18, 1863). A final letter written to Mr. and Mrs. Williams on September 4, 1863, by a cousin, H. B. Williams of the 48th Regt. (Va. Vols.), speaks at greater length on the subject of religion in the camp, and condoles with the parents on the death of their son.” [Source: N. C. Digital Collections]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

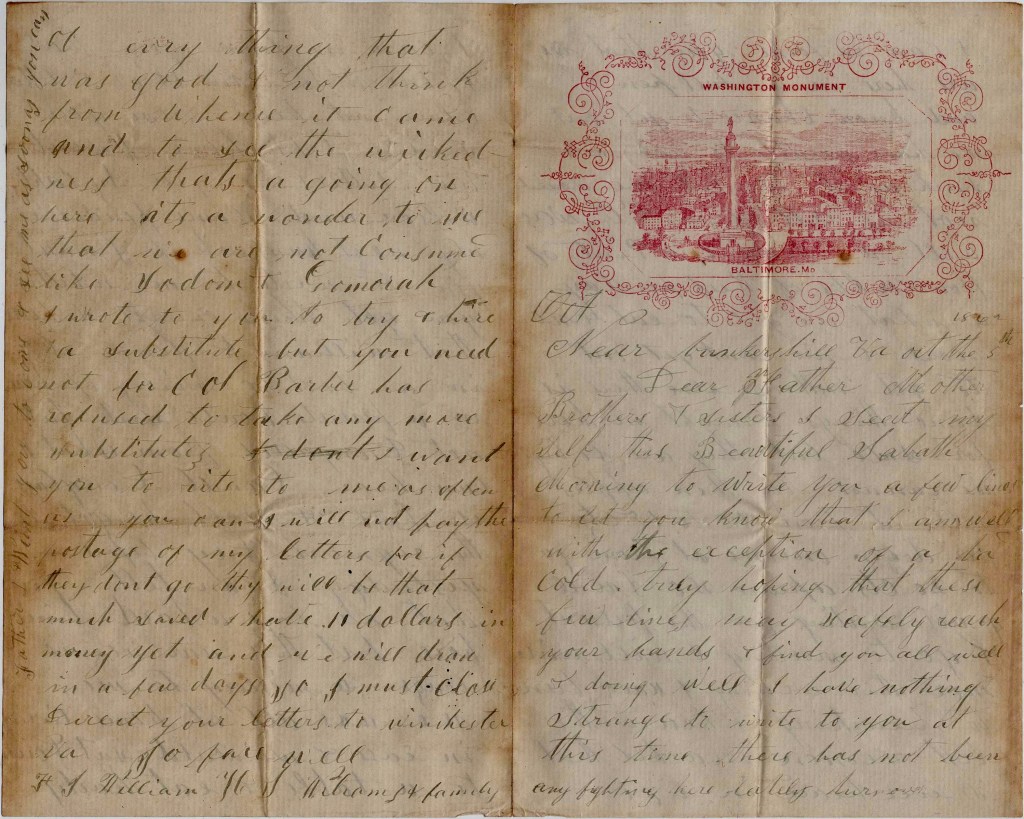

Near Bunker Hill, Va.

October 5th 1862

Dear Father, Mother, Brothers & Sisters,

I seat myself this beautiful Sabbath morning to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well—with the exception of a bad cold—truly hoping that these few lines may safely reach your hands & find you all well & doing well. I have nothing strange to write to you at this time. There has not been any fighting here lately.

I can inform you that we are here in a bull pen and no chance to get out. We have plenty to eat here—such as it is, but we would not if all of our company was well. We draw one pint of flour & one and a half pounds of beef per day is what we get to eat & no more & we can’t get out to get nothing else. There is some things brought in here for sale but they are so high we cannot buy them. Apples sells at from 50 to 75 cents per dozen. Onions at from 10 to 20 cents apiece. So I will quit writing for the present & go to meeting & will write more this evening.

I have been to preaching and heard the best sermon preached that I ever heard in life. I can inform you that I have wrote four or five letters & have not heard from you since I left home. I sent two letters to you by Capt. Wilson and some powder and my neck handkerchief. I want you to write to me whether you got them or not. I hear that William D. Jones is in about 30 miles of here in a private house sick but not dangerous from what I can hear. Daniel Douglass is here & well. He got to the regiment day before yesterday.

I can tell you that we boys have a hard time here but this war is no longer a mystery to me. We was all at home living in ease & we would sit down to a table & eat hearty of everything that was good & not think from where it came. And to see the wickedness thats a going on here—it’s a wonder to me that we are not consumed like Sodom and Gomorrah.

I wrote to you to try & hire a substitute but you need not for Col. [William Morgan] Barber has refused to take any more substitutes. I want you to write to me as often as you can. I will not pay the postage of my letters for if they don’t go, they will be that much saved. I have 11 dollars in money yet and we will draw in a few days. So I must close. Direct your letters to Winchester, Va. So farewell. — F. J. Williams to H. J. Williams & Family

Father, I want you to come and see me as soon as you can.