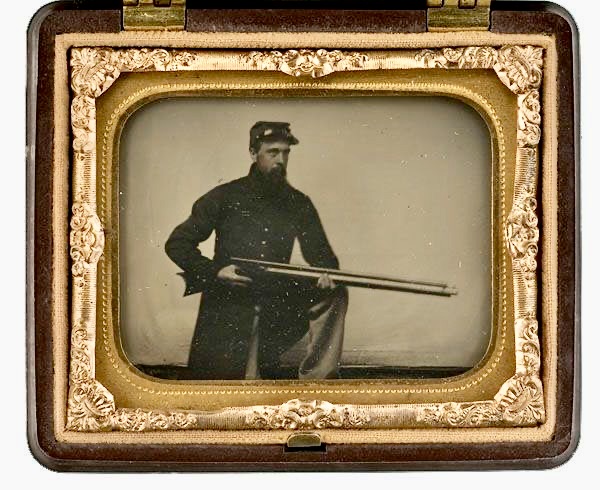

A horizontal view of Colby uniformed in ubiquitous green frock coat kneeling with an early civilian target rifle with telescopic sight adopted for use by Berdan’s famous Sharpshooters.

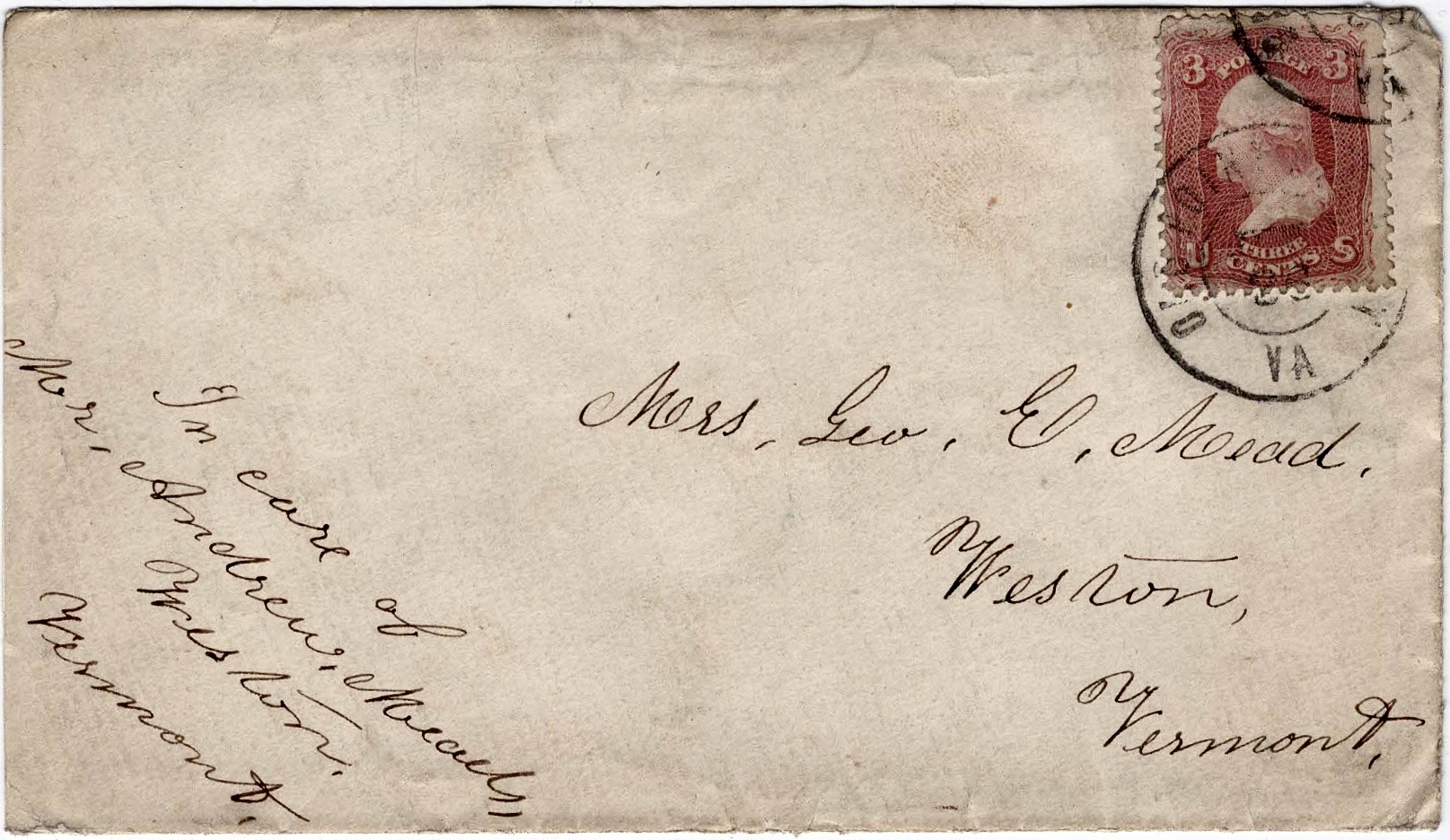

The following letter was written by George E. Mead (1837-1862) who enlisted on 11 September 1861 as a private in Co. F, 1st U. S. Sharpshooters. Prior to his enlistment, George was living in Rutland, Vermont, with his wife of four years, Katherine (Hackett) Mead, and working as a railroad hand. When he enlisted, George and the other recruits were promised breech-loading Sharps rifles, known for their accuracy and high rate of fire. Some recruits brought their own rifles and were told the government would reimburse them $60 if the rifle proved suitable. That promise was never kept.

We learn from the letter that after being in the service for four months, the sharpshooters had not been issued their rifles yet and were still laying in the camp of instruction near Washington D. C. As men were dying off rapidly due to disease without seeing any battlefield, George vented his frustration, “As for my part, if I have got to die in this country, I had rather die on the battlefield with powder and ball, then lay down and die with diseases that prevail amongst our soldiers here in camp, such as measles, small pox, diphtheria fevers, and everything that can be thought of.”

Unfortunately for George, his wish for ending the war and returning home safely was never realized. He died of disease on 9 September 1862 at Alexandria, Virginia, presumably after having been with his comrades in the Peninsula Campaign earlier in the summer.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Camp of Instruction, Washington D. C.

Co. F, Berdan’s Regiment

January 10, 1862

Dear affectionate wife,

As I have nothing to busy myself about but to sit in the corner of my tent and smoke my pipe and keep a little fire in our little brick fireplace, I will write you a few lines to let you know how I am a getting along. I am a gaining from my sickness very fast—much faster than I ever expected to. I have got so I can walk a little but I tumble down every few steps. My legs and joints are very weak yet. The steam of the ground with my measles are pretty tough but I think I come out of it bully before long, but not so quick as I should if I did not have to sleep on the bare ground with nothing under me but my blanket. But such is the poor soldier’s bed and I have got to make the best of it.

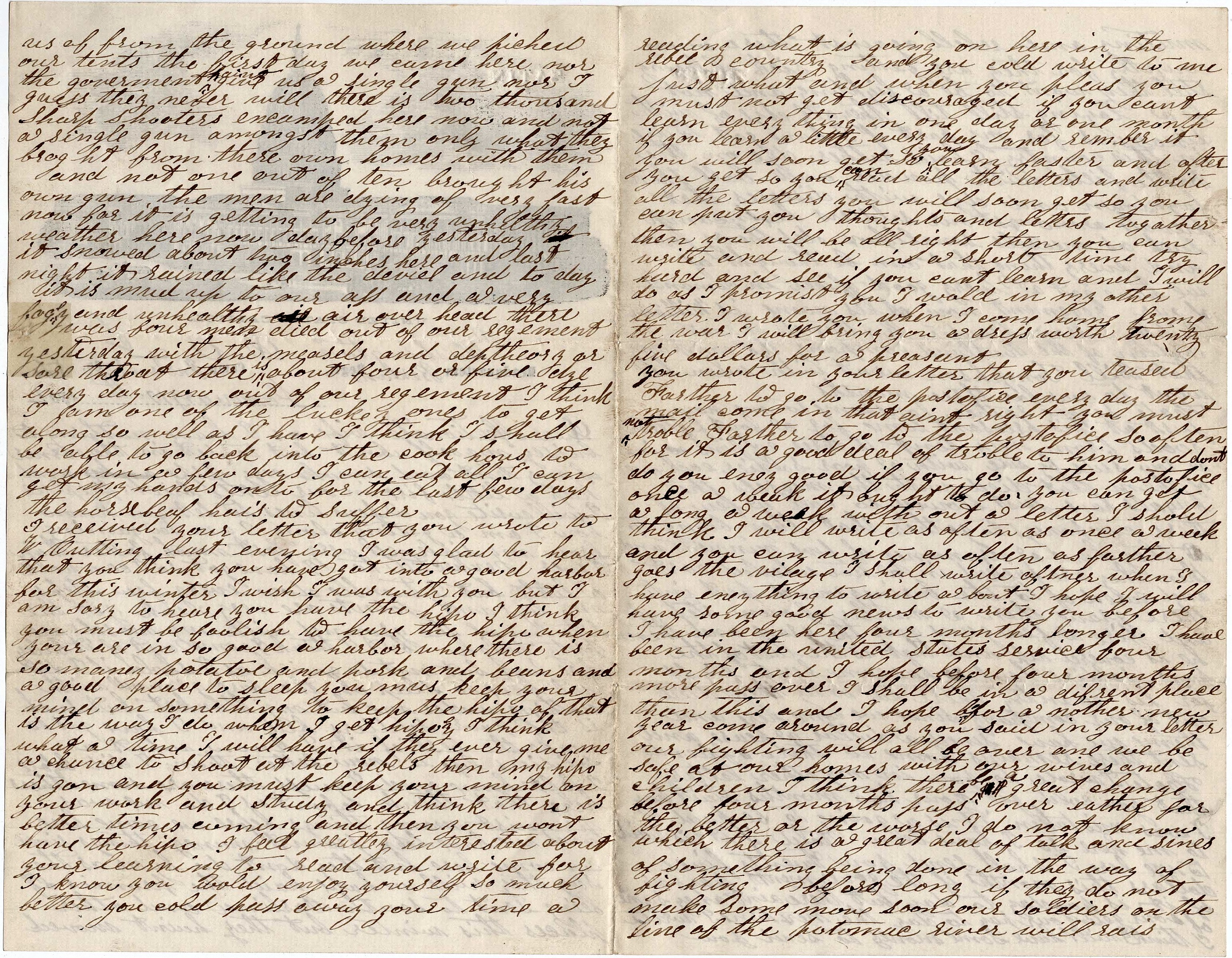

I know what a soldier’s life is now better than I did before I left home and I guess there are some others here that think about as I do. We was promised many things before we come here and we have been promised many things since we came here, but they don’t do by us as they say. They will have had the promise of being sent to South Carolina and other places this winter but they hain’t moved us from the ground where we pitched our tents the first day we came here, not the government hain’t give us a single gun nor I guess they never will. There is two thousand sharp shooters encamped here now and not a single gun amongst them—only what they brought from their own homes with them. And not one out of ten brought his own gun.

The men are dying off very fast now for it is getting to be very unhealthy weather here now. Day before yesterday, it snowed about two inches here and last night it rained like the devil and today it is mud up to our ass, and a very foggy and unhealthy air is over head. There was four men died out of our regiment yesterday with the measles and diphtheria or sore throat. There is about four or five die every day now out of our regiment. I think I am one of the lucky ones to get along so well as I have. I think I shall be able to go back into the cook house to work in a few days. I can eat all I can get my hands onto for the last few days. The horse beef has to suffer.

I received your letter that you wrote to W. Cutting last evening. I was glad to hear that you think you have got into a good harbor for this winter. I wish I was with you but I am sorry to hear you have the hypo. 1 I think you must be foolish to have the hypo when you are in so good a harbor where there is so many potato and pork and beans and a good place to sleep. You must keep your mind on something to keep the hypo off. That is the way I do when I get hypoey. I think what a time I will have if they ever give me a chance to shoot at the rebels, Then my hypo is gone. And you must keep your mind on your work and study and think there is better times coming and then you won’t have the hypo.

I feel greatly interested about your learning to read and write for I know you would enjoy yourself so much better. You could pass away your time a reading what is going on here in the rebel country and you could write to me just what and when you please. You must not get discouraged if you can’t learn everything in one day or one month. If you learn a little every day and remember it, you will soon get so you learn faster. And after you get so you can read all the letters and write all the letters, you will soon get so you can put your thoughts and letters together. Then you will be all right. Then you can write and read in a short time. Try hard and see if you can’t learn and I will do as I promised you I would in my other letter. I wrote you when I come home from the war, I will bring you a dress worth twenty-five dollars for a present.

You wrote in your letter that you teased Father to go to the post office every day the mail came in. That ain’t right. You must not trouble Father to go to the post office so often for it is a good deal of trouble to him and don’t do you any good. If you got to the post office once a week, it ought to do. You can get along a week. It ought to do. You can get along a week without a letter, I should think. I will write as often as once a week and you can write as often as Father goes to the village. I shall write oftener when I have anything to write about. I hope I will have some good news to write you before I have been here four months longer.

I have been in the United States service four months and I hope before four more months pass, I shall be in a different place than this. And I hope before another new year comes around, as you said in your letter, our fighting will all be over and we be safe at our homes with our wives and children. I think there will be a great change before four months pass over, either for the better or the worse, I do not know which. There is a great deal of talk and signs of something being done in the way of fighting before long. If they do not make some move soon, our soldiers on the line of the Potomac river will raise mutiny and rebel against their own country for they are getting sick of lying still. They want to be a fighting and not be a laying still. They all die off with diseases.

As for my part, if I have got to die in this country, I had rather die on the battlefield with powder and ball, then lay down and die with diseases that prevail amongst our soldiers here in camp, such as measles, small pox, diphtheria fevers, and everything that can be thought of. We have got a very good officer in command of our regiment now. His name is William Ripley for Center Rutland. He wsa captain of the Rutland company—the company that Bill Thompson went with when he went to war for three months.

Kate, [it] seems rather lonesome to me now just at this present time for about fifteen rods from my tent is three coffins in a row, side by side, with a poor soldier in each one of them that died with the measles. The bugles have just blowed to call a few of their companies together that they belonged to. They have a ceremony of five minutes and then they are packed in a two-wheeled cart and carried off to the burying ground, put into their grave, [and] then a number of men step up and fire a few guns over the grave adn then he is covered up, and that is the last of the poor soldier who has come here to fight for his country. There has only three died out of our company since we came here and them we have signed a dollar apiece and sent their remains home to their friends.

Kate, I wrote to you in my other letter that you could get your two months State pay. I was mistaken. It is a going to be paid to me here so I have been told. If it is paid to me here, I shall send you twenty-five dollars this month if the government pays us off. It is payday today but there ain’t any sign of our getting our pay today. The next time I write, I think I will have some money to send you.

1 “Hypo” was the term often used to refer to depression. Abraham Lincoln often said he suffered from hypo, but this is the first time I have seen the term used in the thousands of letters I’ve transcribed.