The following letter was written by Newell Dyer (1835-1899), the son of Bela Dyer (1802-1878) and Ruth Ranney (1806-1863) of Plainfield, Hampshire county, Massachusetts. Newell enlisted in Co. C, 31st Massachusetts Infantry on 12 October 1861 and served five months, mustering out on 21 March 1862, discharged for disability.

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

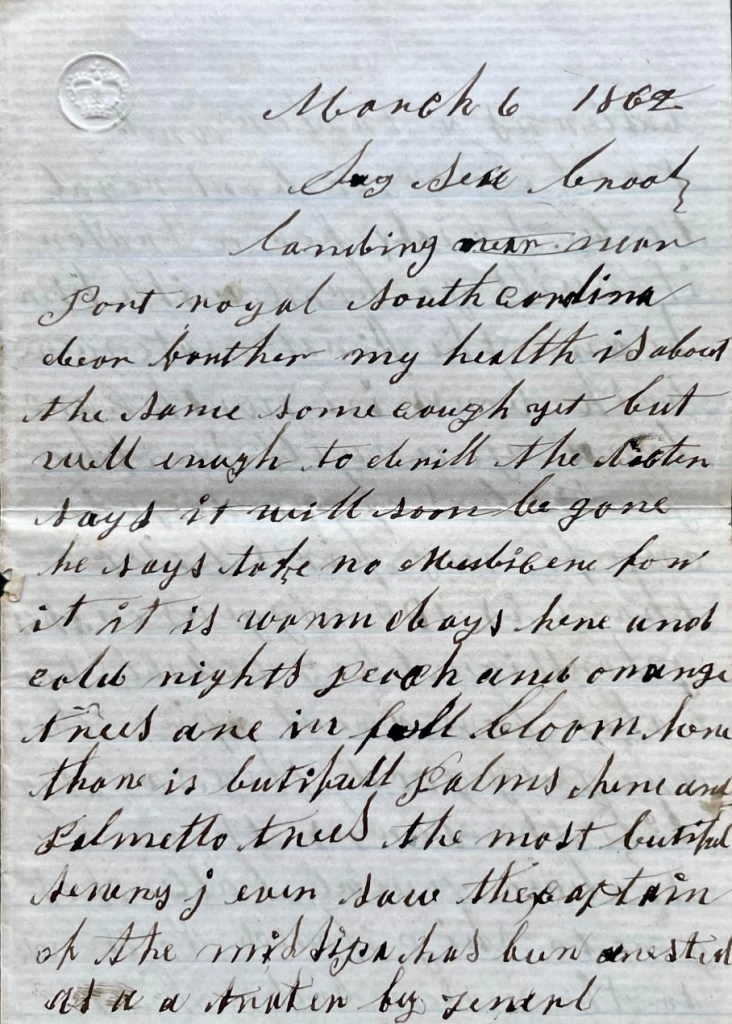

Seabrook Landing near Port Royal, South Carolina

March 6, 1862

Dear Brother,

My health is about the same. Some cough yet but well enough to drill. The doctor says it will soon be gone. He says take no medicine now. It is warm days here and cold nights. Peach and orange trees are in full bloom here. There is beautiful palms here and palmetto trees. The beautiful scenery I ever saw. The captain of the militia has been arrested by General Butler as a traitor and took down to Port Royal to be tried for a traitor. It will go hard with him. He and the first mate were both born in North Carolina. You will see the particulars of our voyage in my first letter.

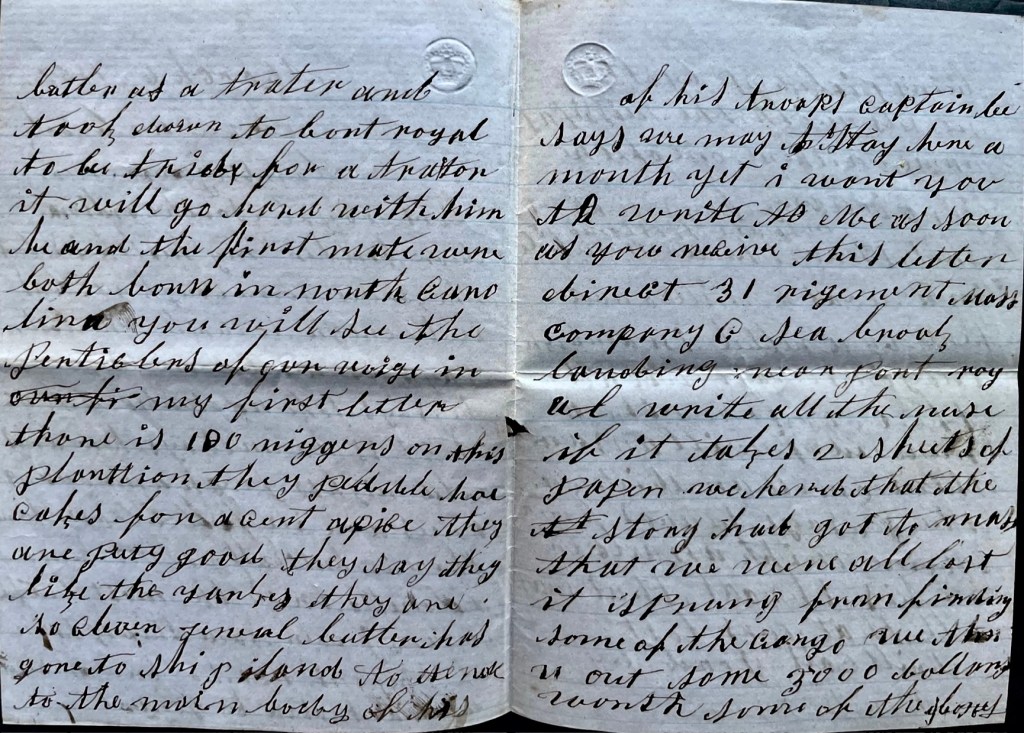

There is 100 niggers on this plantation. They peddle hoecakes for a cent apiece. They are pretty good. They say they like the Yanks. They are [ ]. Gen. Butler has gone to Ship Island to the main body of his troops. Captain B. says we may stay here a month yet. I want you to write to me as soon as you receive this letter. Direct to 31st Regiment Massachusetts. Company C, Seabrook Landing near Port Royal.

Write all the news if it takes two sheets of paper. We heard that the story had got to Massachusetts that we were all lost. It sprang from finding some of the cargo. We threw out some 3,000 dollars worth. Some of the boxes being picked up by other vessels with the [steamer] Mississippi‘s name on them. 1

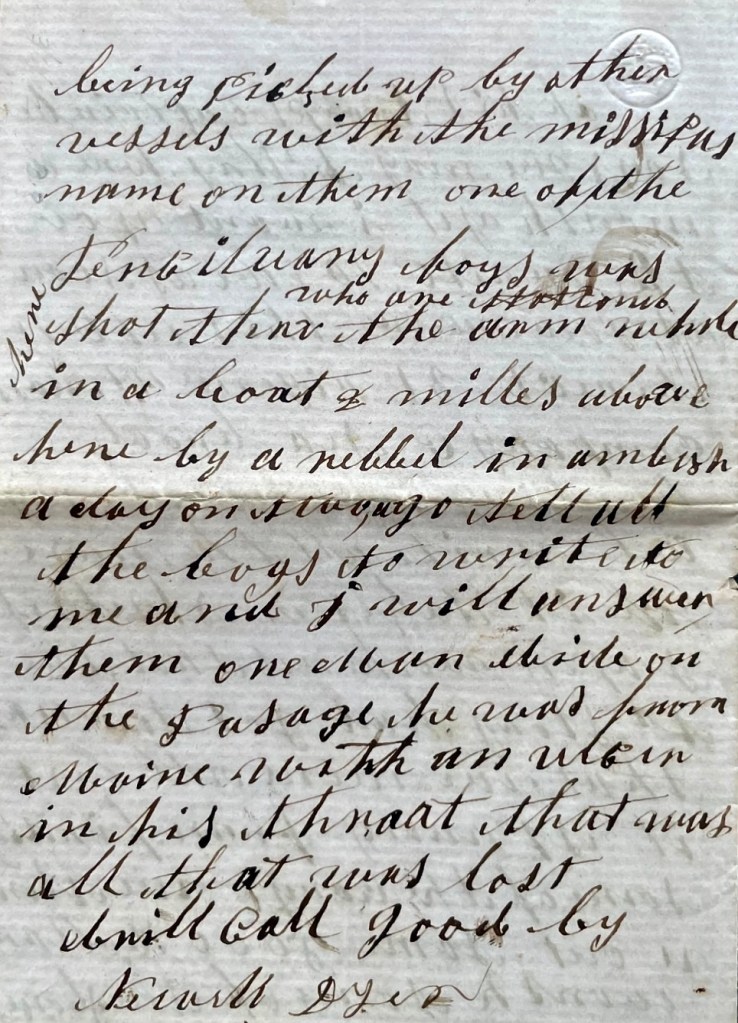

One of the Pennsylvania boys was shot through the arm while in a boat two miles above here by a rebel in ambush a day or two ago. Tell all the boys to write to me and I will answer them. One man died on the passage. He was from Maine with an ulcer in his throat that was all that was lost. I will call goodbye, — Newell Dyer

1 At Boston the 31st Mass., 1,000 strong, and five companies of the 13th Me. embarked on the new transport Mississippi, bound for the Crescent City. In addition to the troops, the vessel carried a heavy cargo of military stores and 1,300 tons of coal…At Fortress Monroe, where we arrived in a brisk gale, Gen. Butler, his wife and maid, and his staff joined us. The voyage was resumed Feb. 25. When near Cape Hatteras we were tempest-tossed. The Captain in bed, locked in his room, was aroused with difficulty, and informed that disaster was imminent. He headed the ship east, standing in that direction until morning. The ice-house, in which was packed quarters of beef, gave way. Beef, barrels of pork, potatoes, rice and other provisions mingled with ammunition muskets and equipments, broken bunks and mangled humanity, rolled and smashed fore and aft’. Hatches were battened down, and Egyptian darkness prevailed, the roar of the storm neutralizing all other sounds. No brush can pain, o pen can describe, the horrors of that tempestuous night. At sunrise of the 27th the ship quivered. We were stranded on Frying Pan Shoals, five miles from shore, and in full view of Fort Macon. Casting the “gipsy,” we found 14 feet of water. The normal draft of the ship was eighteen feet. We were told that but one vessel in like predicament had ever been saved. The anchor was cast, and the ship forged against it, crushing a five inch hole in the side, through which water poured with resistless force. Fortunately, there were water-tight compartments. The men began to murmur, accusing the Captain of being a “Baltimore Secessionist.” For protection he was placed in the charge of the best drilled company on board, commanded by Capt. Fisk, who later became a General...While on the way from Cape Fear to Port Royal Gen. Butler emulated the old lady who tried to mop up the ocean. All the pumps in the steamer were started, and lines of men formed with buckets, trying to bail the water out of the fore compartment. As the hole in the vessel was the size of a large anchor fluke, of course the water in the vessel kept level with that outside, in spite of all that could be done. Sometimes the men on the steamer would move towards the stern, so that the bow would rise, and then the officers would cry, “Go it boys, you are gaining on it!” In a few minutes they would perhaps move the other way, causing the bow to sink and the water to rise in the compartment; then the cry would be, “For God’s sake, hurry, boys, the water is rising!” And that useless labor was continued night and day till March 2, when the steamer reached Port Royal. The next day the Mississippi was taken to Seabrook Landing, about five miles from Hilton Head. The troops were disembarked, the stores unloaded, and the steamer repaired sufficiently to risk finishing the voyage. March 13, the stores having been reloaded on the Mississippi, the 31st Mass. re-embarked, the battalion of the 13th me., taking the steamer Matanzas, and a new start was made for Ship Island. Before leaving the harbor, however, the Mississippi ran aground again on a bank of oyster shells. After taking off the troops, the steamer was pulled off by tugs, the troops put on board again, and (the Captain being removed and a new one appointed) she at last left the harbor. After this nothing occurred worthy of special mention, and both steamers in due time reached Ship Island in safety.” E.B. Lufkin, Co. E, 13th Me., Weld, Me. [National Tribune, March 12, 1885]