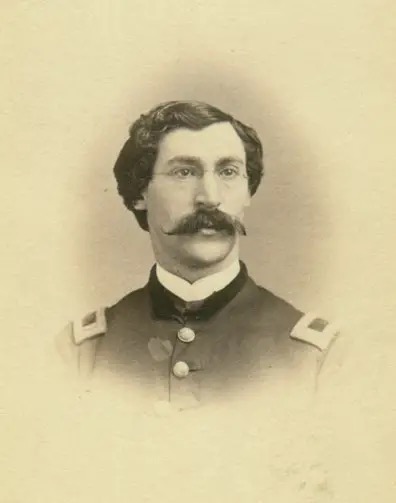

The following letters were written by Dr. Morris Joseph Asch, before and after the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. Morris was born on July 4, 1833, and was the second son of Joseph Morris Asch (1802-1866) and Clarissa Ulman (1812-1869) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His early education was mainly under private tutors and in the autumn of 1848 he entered the University of Pennsylvania where he was graduated on July 2, 1852, with the baccalaureate degree. His Master’s degree was received in course July 3, 1855. He was a member of the Alpha Chapter (University of Pennsylvania) of the P. K. E. fraternity. In the fall of 1852 he entered the Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia from which he received the doctorate in 1855. Soon after graduation Dr. Asch was appointed clinical assistant to Dr. Samuel D. Gross, with whom he remained for several years.

When war was declared and his country called, it was but natural that he should enter the Army where three brothers had already volunteered. He passed the examination for assistant surgeon of the United States Army, which he entered on August 5, 1861. He was on duty at the surgeon-general’s office from August, 1861, to August, 1862. He subsequently became surgeon-in-chief to the Artillery Reserve of the Army of the Potomac, medical inspector Army of the Potomac, medical director of the 24th Army Corps, medical inspector of the Army of the James, staff surgeon of General P. H. Sheridan from 1865 to 1873. Some of the battles of the Civil War in which Dr. Asch participated were Chancellorsville, Mine Run, Gettysburg, The Wilderness and Appomattox Court House. On March 13, 1865, he was brevetted major for faithful and meritorious services during the war. He resigned from the Army of the Potomac on March 3, 1873, and entered into the practice of medicine in New York City, devoting himself largely though not exclusively to the study and treatment of diseases of the nose and throat and holding the position of surgeon to the throat departments of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Manhattan Eye and Ear Hospital. When the American Laryngological Association was formed he was one of its founders, and he was president in the work of the section of laryngology. [Source: American Medical Biographies]

Morris wrote the letters to his brother-in-law, George King—husband of Rachel Rosalie Asch (b. 1835). They were married in New York City in February 1853.

Letter 1

Washington [D. C.]

July 10, 1861

Dear George,

I promised to write you and take the first opportunity to fulfill my engagement although I have nothing to write that you don’t see in the papers before I do. Nobody here is allowed to know anything. It is too near the enemy and if any information was afforded, the secessionists would know it before our own. I had expected to be sent into the field but instead I have been retained here to assist in establishing a military hospital. There are several here but a larger one is needed and to that duty I am assigned. It is abominable there is so much red tape to go through. If we want an ambulance or any important article, I go to the Surgeon General. He send me to the Medical Director. He approves and I go to General Mansfield. He approves and I go to the quartermaster. He says that he can’t give it without an order from Gen. Meigs. I go to him and he says that the President’s orders are not to issue anything except on Gen. Scott’s order. I go to Gen. Scott and he says that he can’t be troubled with such details. I go back to the quartermaster to ask what the devil he means by sending me on such a round and he says that there is no use coming for he hasn’t got what I want. That is the way that everything has to be done here so you can imagine what a pleasant time one has to establish a hospital with furniture for 400 men. But we are pretty nearly through and I hope that when the thing is in operation they will send me off with McDowell.

I went to Alexandria the other day and rode out to the outposts and round the pickets to Arlington. It is a real secession country. I asked in Alexandria where the Colonel lived and a fellow said that he didn’t know any such crowd. Shepard 1 the Provost Marshal said that they were tired of kicking the fellows but that it was the only thing that they could do with them. Alexandria looks deserted. You hardly see a soul in the streets. All the houses and stores are shut and the horses feet sounded as if we were in a deserted city.

From there we rode out to the [New York Fire] Zouave camp and saw [Col. Noah L.] Farnham and his men. They are good soldiers but need discipline. Farnham gave a captain some order about his men’s muskets and he said that he’d be damned if he would. There are some strong earth works around the town and whole round to Washington is one line of pickets and camps.

We took dinner at the Minnesota camp 2 (the best shots I ever saw hitting the target as big as your hat every shot at 230 yards) and from there passed through the camp to the earthworks of the 69th and from there to Arlington, Gen. McDowell’s headquarters, and from there to Washington. The entrenchments are very strong and extend over the whole round. We passed through the Garibaldi Guard on the march and they stoned us for going through their lines on a run. We had a couple of secession horses that were captured at Mathias Point by Capt. [James H.] Ward and the red shirts scared them. We went out as far as the pickets would let us towards Fairfax. We wanted to see the “seceshers” but didn’t get a chance. We were on horseback all day and was pretty well used up when we got home.

Give my love to Rachel and Judah and the children & let me hear from you. Regards to May. 3 Tell him his hats looked fine on the Garibaldi’s. Direct to Dr. Asch, USA, Washington D. C.

Yours, — Morris

1 Lieutenant Charles H. Shephard of Co. B, 5th Massachusetts Infantry was serving as the Provost Marshal at the time of Morris’ visit to Alexandria in July 1861.

2 The 1st Minnesota saw heavy fighting on Henry House Hill at 1st Bull Run. They were one of the last regiments to leave the field and suffered one of the highest number of casualties of the Union regiments engaged—49 killed, 107 wounded, and 34 missing. Just prior to advancing on Manassas, the regiment was encamped at Camp Forman at the reservoir on the Little River Turnpike near Alexandria.

3 Morris was probably referring to Lewis May, a hat maker at 43 Broadway in New York City. The letter suggests that the hats supplied to the Garibaldi Guards (39th New York) came from May. The regiment was famous for their distinctive Bersaglieri hats, red shirts, and black gaiters when they first took the field in 1861. Lewis was active in politics and was one of the featured speakers at Union Square War Meeting in April 1861 in which he encouraged the Germans to organize themselves into a regiment and march to Washington in its defense. German’s comprised the greatest percentage of the foreign born members of the 39th New York, Garibaldi Guard. [Source: New York Herald, 24 April 1861]

Letter 2

Columbian Hospital 1

July 29, 1861

Dear George

Now that things look a little better, I hope that you have got out of the desponding mood that you were in when you last wrote. In fact, there is no reason why you should not be. The thrashing that we got will only make us more alive to our deficiencies and our next army will be worth a dozen of the last. Anyhow, we hurt them as bad as they did us, and if it were not for the number of our prisoners that they have, I think that we would be the best off. But one government liberates every rebel that it catches and when they catch ours we have nothing to exchange.

As to the battle itself from all that I can hear from regulars who were not scared and from volunteers who were, our men had the best of it in every way until forced to give up by hunger & exhaustion. They had nothing to eat since the night before and our fine politician officers took them for miles into action on the double quick and then gave them no rest. The regulars found that their men couldn’t stand that game so they rested them for an hour or two before they went in again and then did good service. If it had not been for that cowardly panic, I believe that we would have remained masters of the field.

By the way, some of your New York Regiments behaved very well—the 69th and 71st and 14th [Brooklyn], but others lost the battle through their cowardice. The Fire Zouaves behaved in the most cowardly manner and could not be brought up for a charge—squatting and firing till they ran away and some have not turned up yet they ran so far. The enemy ran too. An officer told me that we charged and they ran. Then they charged and we ran. Then we charged and they ran. Then they charged and we ran farther and faster than they did. There is no doubt but that they must have been used up and scared or they would have advanced on Washington—for they could have taken it up to Wednesday for there was no discipline of any kind. Troops were straggling all over the country and there were not a half dozen regiments together. People were scared and if Beauregard had any chance of fighting he would have been here.

They say today that Johnston is about to attack Banks but I presume that he is prepared for him. The enemy’s lodd must have been severe. Our artillery worked well but we had not enough of it. An officer of Sherman’s Battery 2 told me that after silencing a battery, he went out to reconnoiter and saw a regiment of Louisiana Zouaves coming up a ravine to outflank them. They turned their guns—six pieces—on them and as they came in range, they let drive with grape and canister into them and made lanes right through them and routed them in short order.

[Capt. Romeyn] Ayres’ Battery got their range on a railroad crossing an open space between the woods where reinforcements were being brought up, and as the head of the train came in sight, let fly and smashed five cars with troops in all to pieces. A man who escaped from them and was employed by them in the hospital says that they have 2800 wounded. We have some of our wounded here but not many. Most of them are in town.

I have to thank you and May for that beautiful hat that you sent me. I mean to write to May soon but till I do, consider this as a joint letter to you both. The hat has been very much admired. It is the handsomest that has been seen here. You may imagine that I have to steal some time to write when I tell you that I have been four hours writing this letter. I am officer of the day and have to receive and discharge patients, attend to the business of the house, and even bury the dead—and consequently am hopping up and down every five minutes which accounts for the gaps in my letter. We have about 225 patients in the house and more coming in every hour.

Have you hot weather in New York? Here is is delightful. It is always cool and a pleasant breeze always blowing so that it scarcely seems to me that I am south of Philadelphia. I don’t know who your friend, the recruiting captain in Broadway, may be but I do know that he is a damned impertinent fellow and I will tell him so if I see him.

Give my love to Rachel and the children and Judah. Tell Ally 3 that I will bring him a secession sword of the first battlefield that I get to. My respects to the family. Ask May to write. Yours affectionately, — Morris

Direct to Columbian Hospital, Box 266, P.O., Washington

1 Built in 1820, the Columbian College was appropriated by the government on 13 July 1861 to be used as a hospital. It was located on Meridian Hill, west of 14th Street Road. The hospital was initially operated in the Washington Infirmary at the college until it burned in November 1861 at which time the hospital was relocated to the main College building.

2 Co. E, 3rd U. S. Artillery, or more commonly called “Sherman’s Battery,” was commanded by Thomas W. Sherman.

3 “Ally” was Albert G. King, b. 1854, the son of George & Rachel (Asch) King.