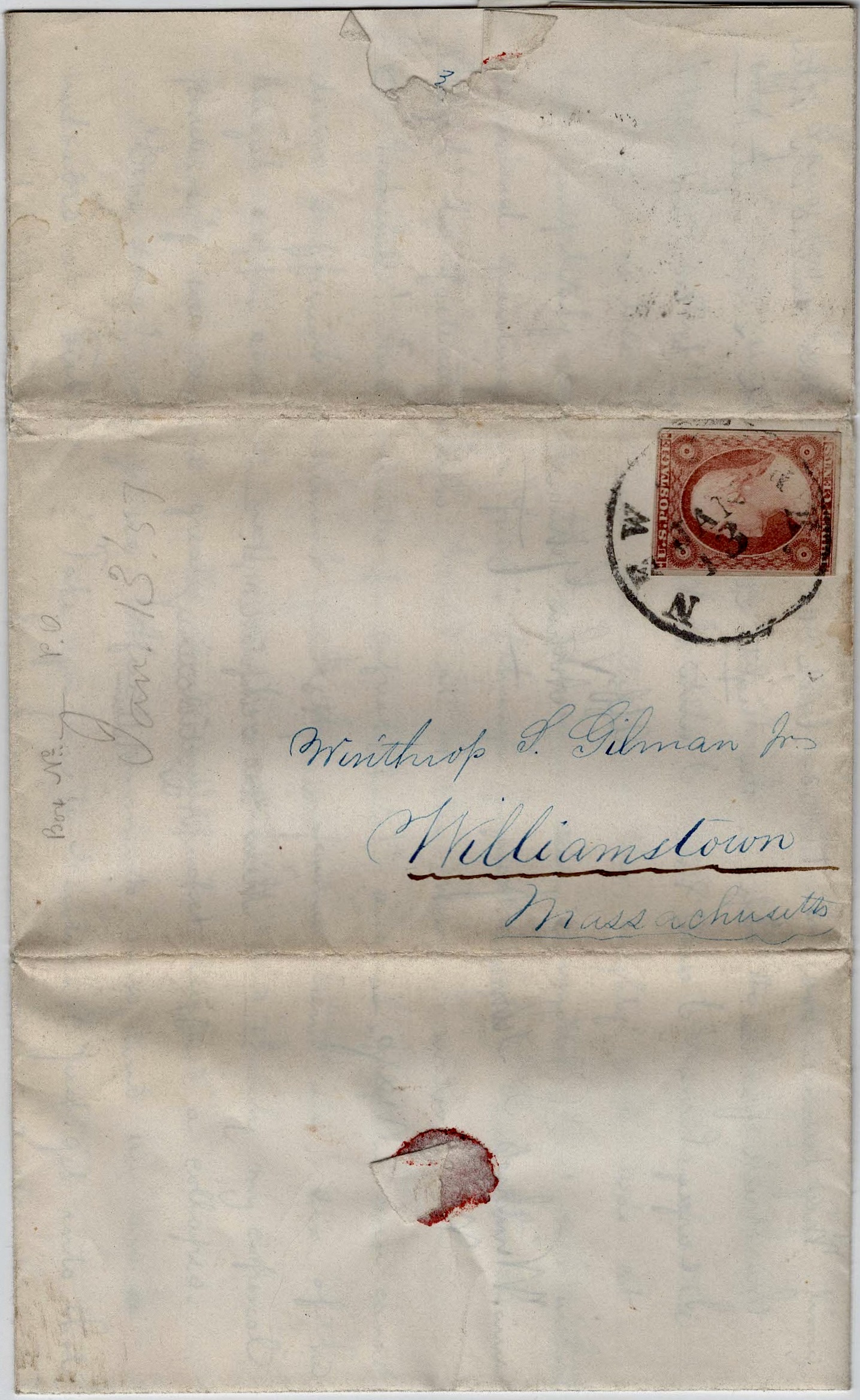

The following letter was written in January 1857 by Arthur Gilman (1837-1909), the son of Winthrop Sargent Gilman, Sr. (1808-1884) and Abia Swift Lippincott (1817-1902). He wrote the letter to his younger brother Winthrop (“Wint”) Sargent Gilman, Jr. (1839-1923) attending Williams College in Massachusetts.

Arthur’s father was a businessman who had a wholesale business in Alton, Illinois, and St. Louis, Missouri, before settling in New York City as an agent of the St. Louis firm in 1848. In 1860 he opened a banking house known as Gilman, Son, & Co. Arthur worked for his father in the bank for a while and then devoted his life to the education of women through the Harvard courses (the “Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women”). In 1886, he established a school for girls which he called the Cambridge School but it was more generally known by his name.

Arthur’s letter recounts a day-long journey from New York City to Newburgh, a distance of 60 miles up the Hudson River on a frigid day in January 1857. He embarked on a river steamer to Fishkill Landing and subsequently traversed the ice on a heavily laden sleigh, a choice he later deemed unwise.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

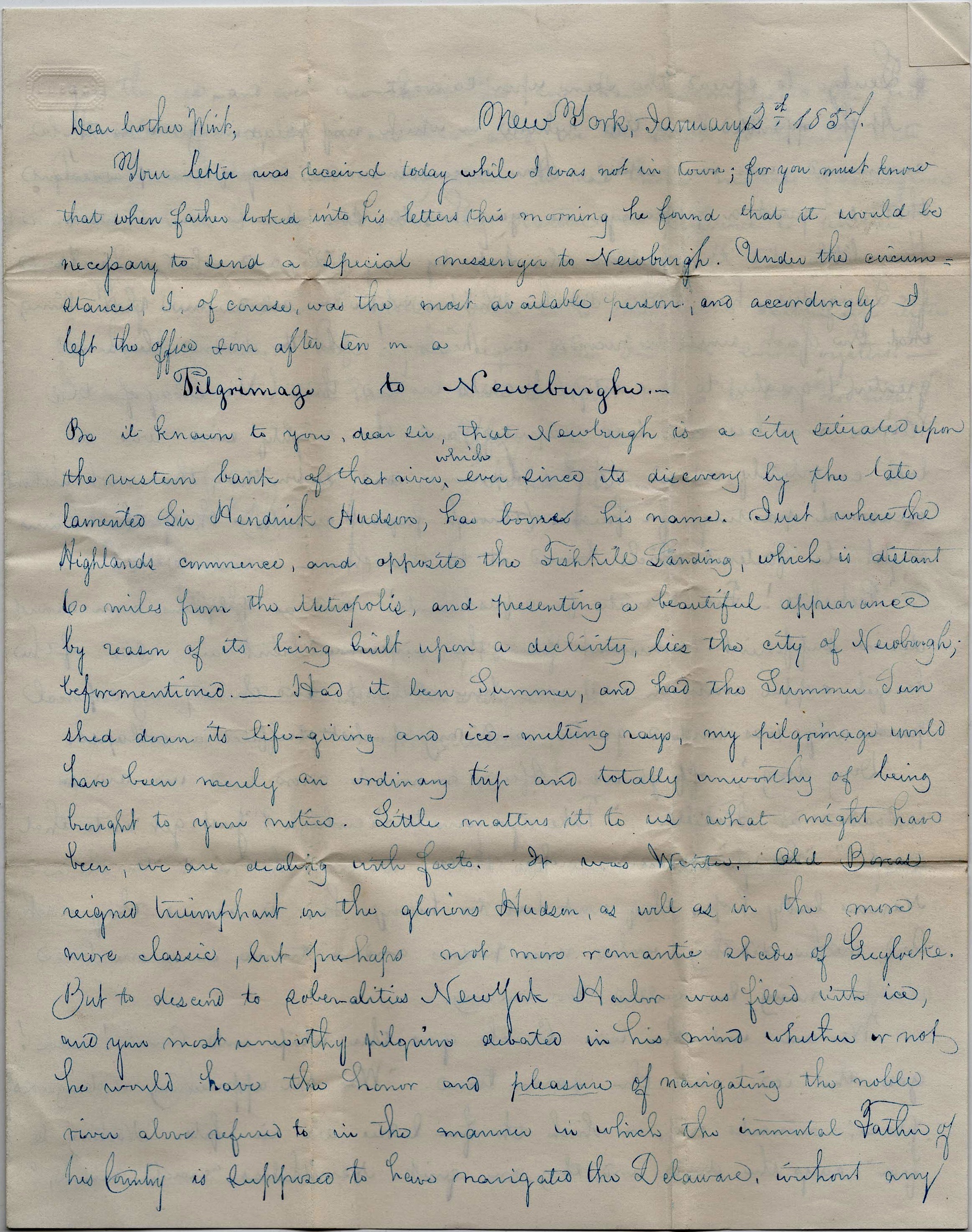

New York [City]

January 12, 1857

Dear Brother Wint,

Your letter was received today while I was not in town, for you must know that when father looked into his letters this morning, he found that it would be necessary to send a special messenger to Newburgh. Under the circumstances, I, of course, was the most available person and accordingly I left the office soon after ten on a…

Pilgrimage to Newburgh.

Be it known to you, dear sir, that Newburgh is a city situated upon the western bank of that river which ever since its discovery by the late lamented Sir Hendrick Hudson has borne his name. Just where the Highlands commence and opposite the Fishkill Landing, which is distant 60 miles from the Metropolis, and presenting a beautiful appearance by reason of its being built upon a declivity, lies the City of Newburgh, before mentioned.

Had it been summer and had the summer sun shed down its life-giving and ice-melting rays, my pilgrimage would have been merely an ordinary trip and totally unworthy of being brought to your notice. Little matters it to us what might have been; we are dealing with facts. It was winter. Old Boreas reigned triumphant on the glorious Hudson as will as in the more classic, put perhaps not more romantic shades of Greylocke.

But to descend to soberalities, New York harbor was filled with ice and your most unworthy pilgrim debated in his mind whether or not he would have the honor and pleasure of navigating the noble river above referred to in the manner in which the immortal Father of his Country is supposed to have navigated the Delaware, without any [Emanuel] Leutze to spread the scene upon canvas.

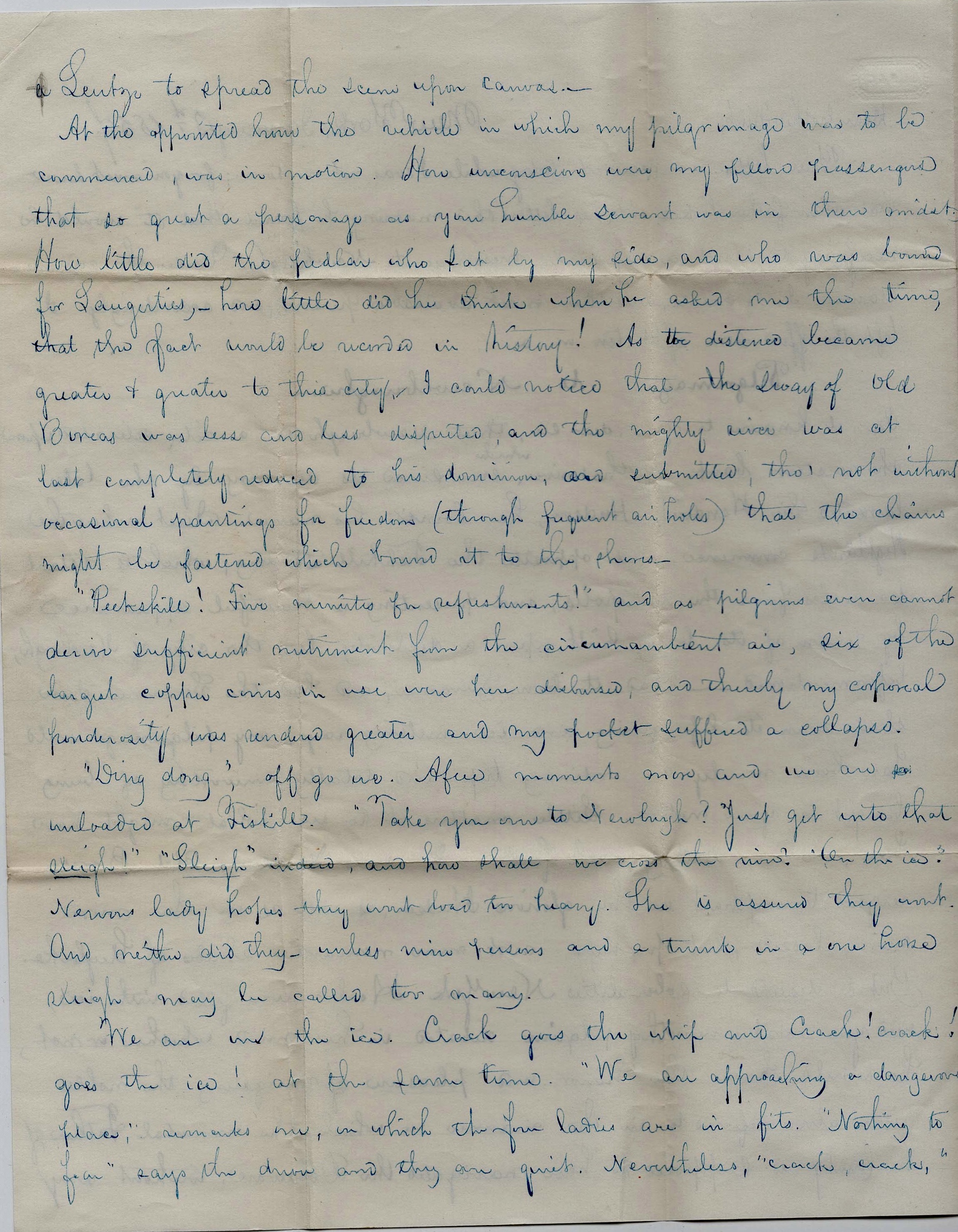

At the appointed hour the vehicle in which my pilgrimage was to be commenced was in motion. How unconscious were my fellow passengers that so great a personage as your humble servant was in their midst. How little did the pedlar who sat by my side and who was bound for Saugerties,—how little did he think when he asked me the time that the fact would be recorded in history! As the distance became greater and greater to this city, I could notice that the sway of Old Boreas was less and less disputed and the mighty river was at last completely reduced to his dominion and submitted, tho’ not without occassional pantings for freedom (through frequent air holes) that the chains might be fastened which bound it to the shore.

“Peekskill! Five minutes for refreshments!” and as pilgrims even cannot derive sufficient nutriment from the circumambient air, six of the largest copper coins in use were here disbursed and thereby my corporeal ponderosity was rendered greater and my pocket suffered a collapse.

“Ding dong,” off go us. A few moments more and we are unloaded at Fishkill. “Take you over to Newburgh? Just get into that sleigh!” Sleigh indeed, and “how shall we cross the river?” “On the ice.” Nervous lady hopes they won’t load too heavy. She is assured they won’t. And neither did they, unless nine persons and a trunk in a one horse sleigh may be called too many.

We are on the ice. Crack goes the whip and crack! crack! goes the ice! at the same time. “We are approaching a dangerous place,” remarks one on which the four ladies are in fits. “Nothing to fear,” says the driver and they are quiet. Nevertheless, “crack, crack” goes the ice and we are there. Yes, we have accomplished the feat. A mile of ice is in our rear and we are safe! I hurried onto terra firma determined on my return to use those means of conveyance with which I was endowed by nature in preference to another sleigh ride.

My business over, I trotted back [over the ice] with my arms doubled up after the Greek fashion. Safe on the right side, I took some oysters! I came home. I am here. I write to Whit. I go to bed. Good night!

Affectionately, — Arthur Gilman

P. S. January 13th. Alice had a comfortable night. Affectionately, — Arthur.