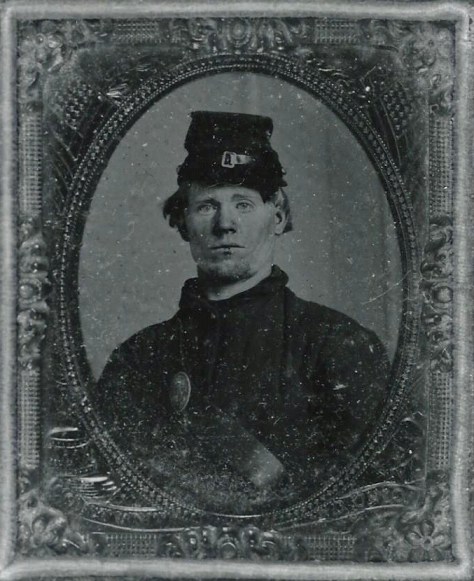

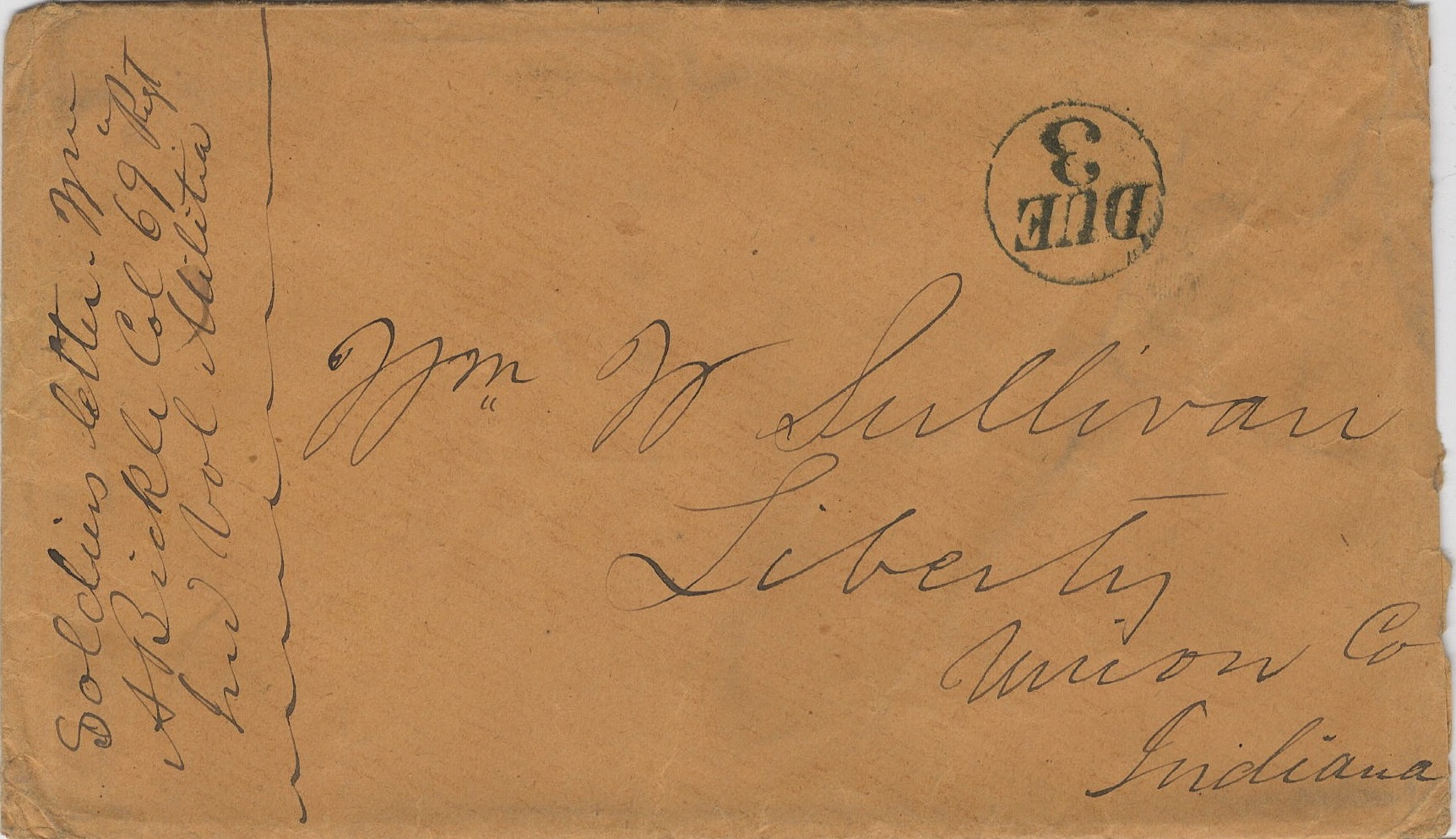

The following letter was written by 39 year-old wagon maker James Perkins (1823-1863) of Clifton, Union county, Indiana. James enlisted on 9 August 1862 in Co. G, 69th Indiana Infantry. He died of chronic diarrhea while in the service at St. Louis, Missouri, on 27 July 1863.

James was born, raised, and married in Kennebec county, Maine. His wife, Evira F. (Wade) Perkins died in January 1861 and left him with four children born between 1848 and 1857. After James’ death, the Wade family stepped in as guardians.

The 69th Indiana, along with other Union forces, suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Richmond on August 29–30. The overwhelming Confederate victory led to the capture of a substantial number of Union troops, including the entire 69th Indiana regiment. Following their capture, the soldiers of the 69th were paroled, a prevalent practice at the time wherein captured soldiers were released with the stipulation that they would refrain from combat until formally exchanged. Perkins’ letter was written during this period of time while still in Kentucky.

Later in September 1862, they returned to Indianapolis to await their official exchange. It was during this period of enforced inactivity that controversy emerged; Union authorities exhibited reluctance to expedite the exchange and reintegration of the captured and paroled soldiers into active duty. This created a phase of idleness and disarray, raising serious concerns regarding the regiment’s preparedness and morale. Once officially exchanged and reorganized, the regiment distinguished itself in several major campaigns, notably the Vicksburg Campaign and the Red River Campaign. However, the memory of the calamity at Richmond and the ensuing period of compulsory inaction remained a poignant and bitter chapter in its early history.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Four miles south of Louisville

September 9th 1862

Mr. Sullivan, sir,

How the thing looks outside of this horrible place I don’t know, but as near as I can learn, we are in an awful fix. There is great dissatisfaction here among our broken regiment. They say they will die before they will consent to consolidate with any other. The 14 Kentucky wants us but we will not go in. We think our Kentucky officers are not all right. We have many among us that is sick, many wounded that wants to go home but cannot leave camp unless pronounced by the doctor very dangerous. One man laid here on the ground and died day before yesterday. We have not got 50 men in our regiment that is well enough to bear arms and what will be our destiny, you know as well as we. We think we have been used worse than dogs. Col. Bickle we think is doing all he can to get us home but I guess he will not succeed.

We are in Kentucky and we must do as they do but if we was in Indiana, I would not think much of Kentucky. They are waiting to know how the scale will tip. But we might as well laugh as cry. Crying will do no good although I have not tried it yet. Neither have I laughed much either but I think if I was to your place, it would be the first thing I’d do. I think as little of home and its pleasures as I possibly can.

Freeman Ward and Wallace Stanton are my messmates. We have two blankets between us. We sleep together. We try to take a little comfort but hard to get at. We have no tents. We sleep on the damp ground—no covering over us but the heavens. Old Mr. Preston came here last Wednesday and stayed till yesterday. He said if he had heard how we was used, he could[n’t have] believed it but he said he should go home and tell the tale anyhow.

There is a fellow in camp that cut his foot off splitting wood yesterday morning [and] can never be fit for duty, but he cannot get home now—even to the hospital. There is a nasty creek running through our campground and thousands of dead fish in it. We have no water nearer than one mile fit to drink and that is worse than your slop. I think I would be as glad to see you as you was to see me at Maine. If I knew you could leave home and come here safe and get back safe, I should have you come and see me—perhaps for the last time. But I do not want you to come bad enough to endanger your own life for you very well know that I have too much love and respect for you all to endanger your lives to please me. I have already asked many favors of you which has been cheerfully granted, I believe.

I did not expect when I left your house to change my situation for the better. I did not come because I wanted to. I did not come because I expected to find an easy time. But I came because my country called me. I came for the welfare of my children and your children which I think as much of as I do of my own. But it will not do to dwell on thoughts like these.

There is 6,000 people [with]in sound of my voice. No place you might say to be lonesome. But the most of them will leave very soon. Everyone seems to be in for himself and fighting mad. We had someone say there would be a speedy compromise and the reply to that was to point of bayonet, but that may be our only chance—God only knows.

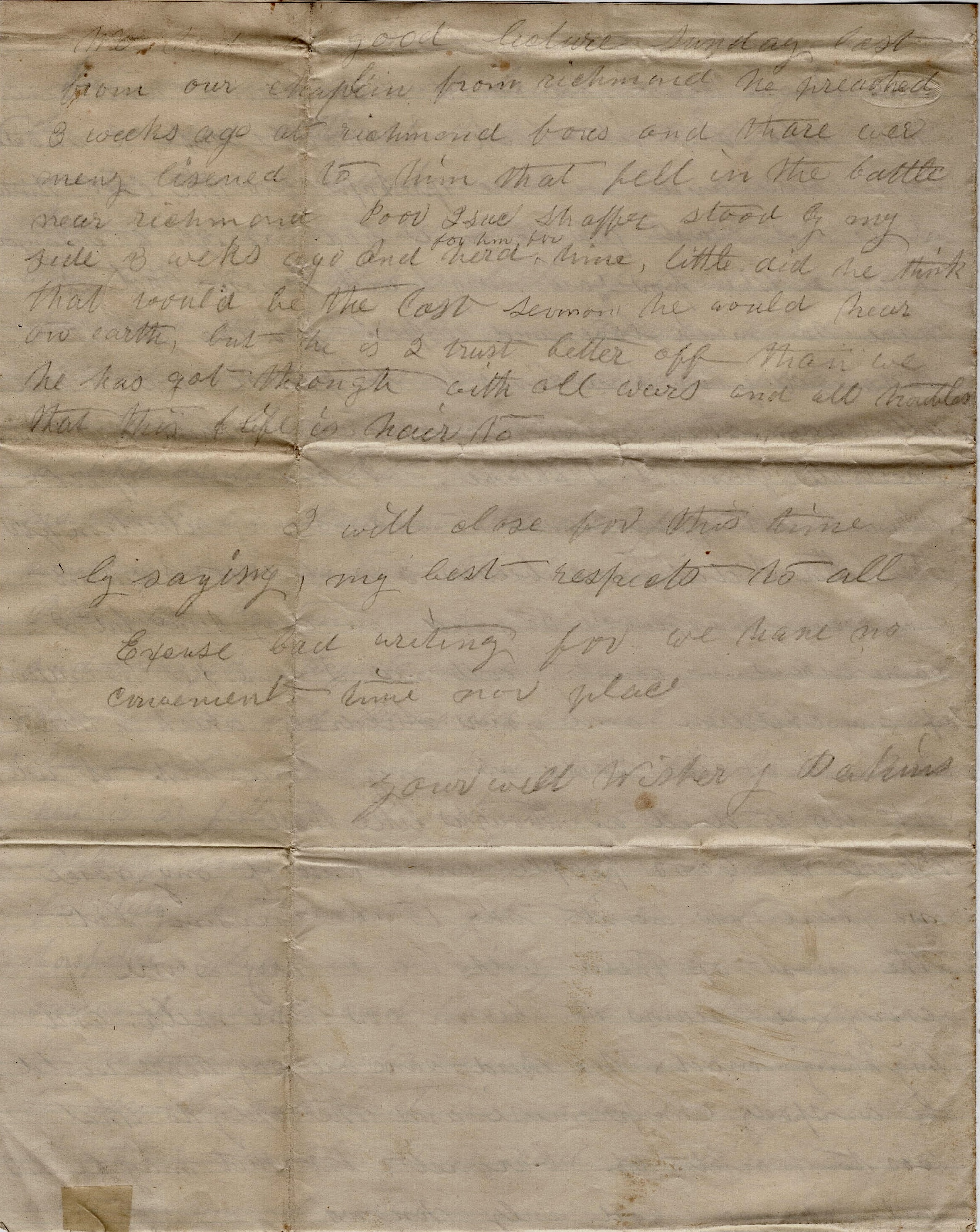

We had a good lecture Sunday last from our Chaplain from Richmond. He preached three weeks ago at Richmond for us and there every man listened to him that fell in the battle near Richmond. Poor Isaac Shaffer stood by my side three weeks ago and heard him; little did he think that would be the last sermon he would hear on earth. But he is, I trust, better off than we. He has got through with all wars and all troubles that this life is near to.

I will close for this time by saying my best respects to all. Excuse bad writing for we have no convenient time nor place. Your well wisher, — J. Perkins