The following letter was written by Gabriel Andrew Cornish (1833-1850), the 16 year-old son of Jared Bradley Cornish (1810-1849) and Saphronia Louisa Cornish (1806-1880) of Algonquin (formerly called Cornishville or Cornish Ferry), McHenry county, Illinois. We learn from the letter that Gabriel’s father was on his way to California when he wrote the letter in mid-August 1849, having traveled at least as far as Fort Laramie at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers in present day Wyoming. He was most likely traveling with a party of “49ers” on their way to the gold fields of northern California. If he made it to California—which is doubtful, he didn’t stay for the date of his death is given as 10 October 1849 and he is apparently buried in La Grange, Walworth county, Wisconsin.

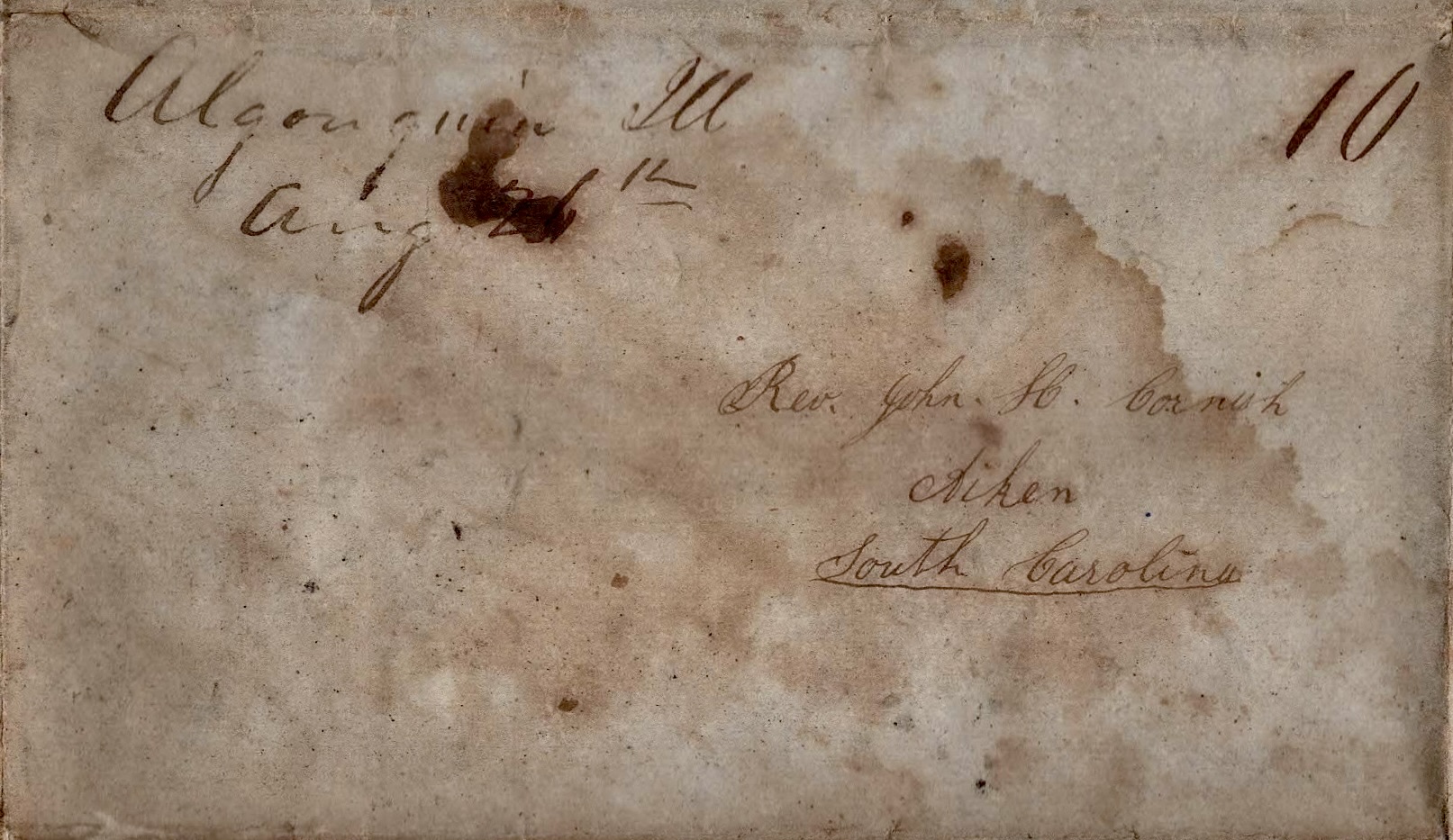

Gabriel wrote the letter to his uncle, Rev. John Hamilton Cornish (1815-1878), a native of Lanesborough, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, and the son of Andrew Hiram and Rhoda (Bradley) Cornish. When John was still a child, the family moved to the Michigan Territory, and it was from there that John left home in 1833 to attend Washington College in Hartford, Connecticut (Washington College changed its name to Trinity College in 1845). It was from there that he graduated in 1839 and later enrolled at the General Theological Seminary, though he never graduated from that institution. He moved to Edisto Island, off the South Carolina coast in January of 1840 and began tutoring the children of E. Mikell Seabrook. By 1843 he became a minister, ordained in the Episcopal Church, serving a number of different churches in the Sea Island and Carolina Low-country. By 1846, he had settled down at the St. Thaddeus Episcopal Church in Aiken, South Carolina. He married Martha Jenkins and with her had six children—Rhoda, Mattie, Mary, Sadie, Ernest, and Joseph Cornish. John Cornish died in 1878. [Sources: The Inventory of the John Hamilton Cornish Papers (Mss 01461), Wilson Library, at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.]

See also—1839: Andrew Cornish to John Hamilton Cornish on Spared & Shared 8.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

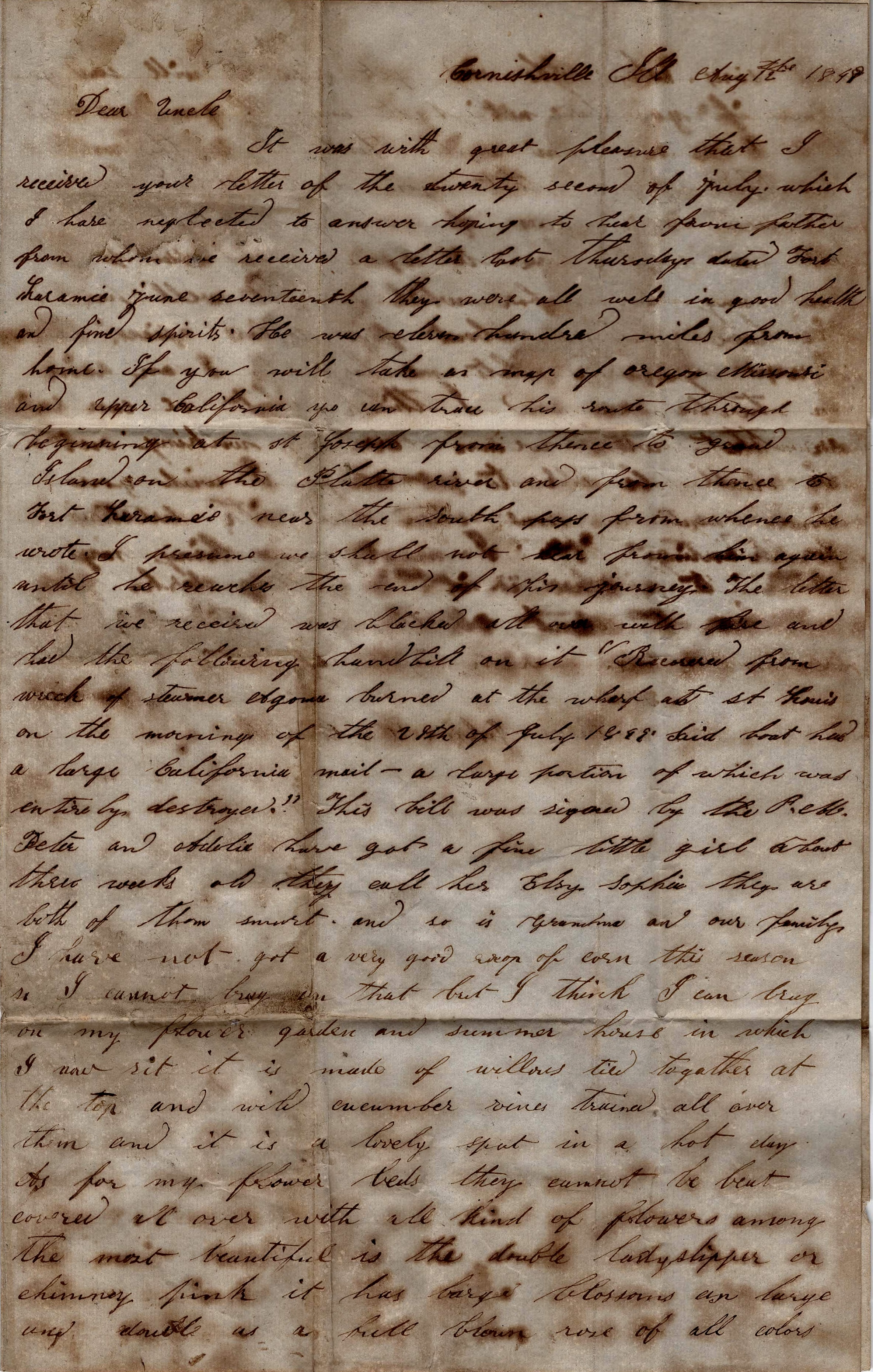

Cornishville, Illinois

August 12th 1849

Dear Uncle,

It is with great pleasure that I received your letter from the twenty-second of July which I have neglected to answer hoping to hear from father from whom we received a letter last Thursday dated Fort Laramie, June 17th. They were all well, in good health and fine spirits. He was eleven hundred miles from home. If you will take a map of Oregon, Missouri, and Upper California, you can trace his route through beginning at St. Joseph, from thence to Grand Island on the Platte river, and from thence to Fort Laramie near the South Pass from whence he wrote. I presume we shall not hear from him again until he reaches the end of his journey.

The letter that we received was blacked all over with fire and had the following hand bill on it, “Recovered from wreck of steamer Algoma burned at the wharf at St. Louis on the morning of the 28th of July 1849. Said boat had a large California mail—a large portion of which was entirely destroyed.” This bill was signed by the P. M. [postmaster]. 1

Peter [Arvedson] and [sister Hannah] Adelia have got a fine little girl about three weeks old. They call her Elsy Sophia. They are both of them smart and so is Grandma and our family. I have not got a very good crop of corn this season so I cannot brag on that but I think I can brag on my flower garden and summer house in which I now sit. It is made of willows tied together at the top and with cucumber vines trained all over them and it is a lovely spot in a hot day. As for my flower beds, they cannot be beat, covered all over with all kind of flowers. Among the most beautiful is the double ladyslipper or chimney pink. It has large blossoms as large and double as a full blown rose of all colors and sizes. When the seed gets ripe, I will send you some if you have not got any. If you was only here, I am sure you would think it is the most beautiful place that you ever see.

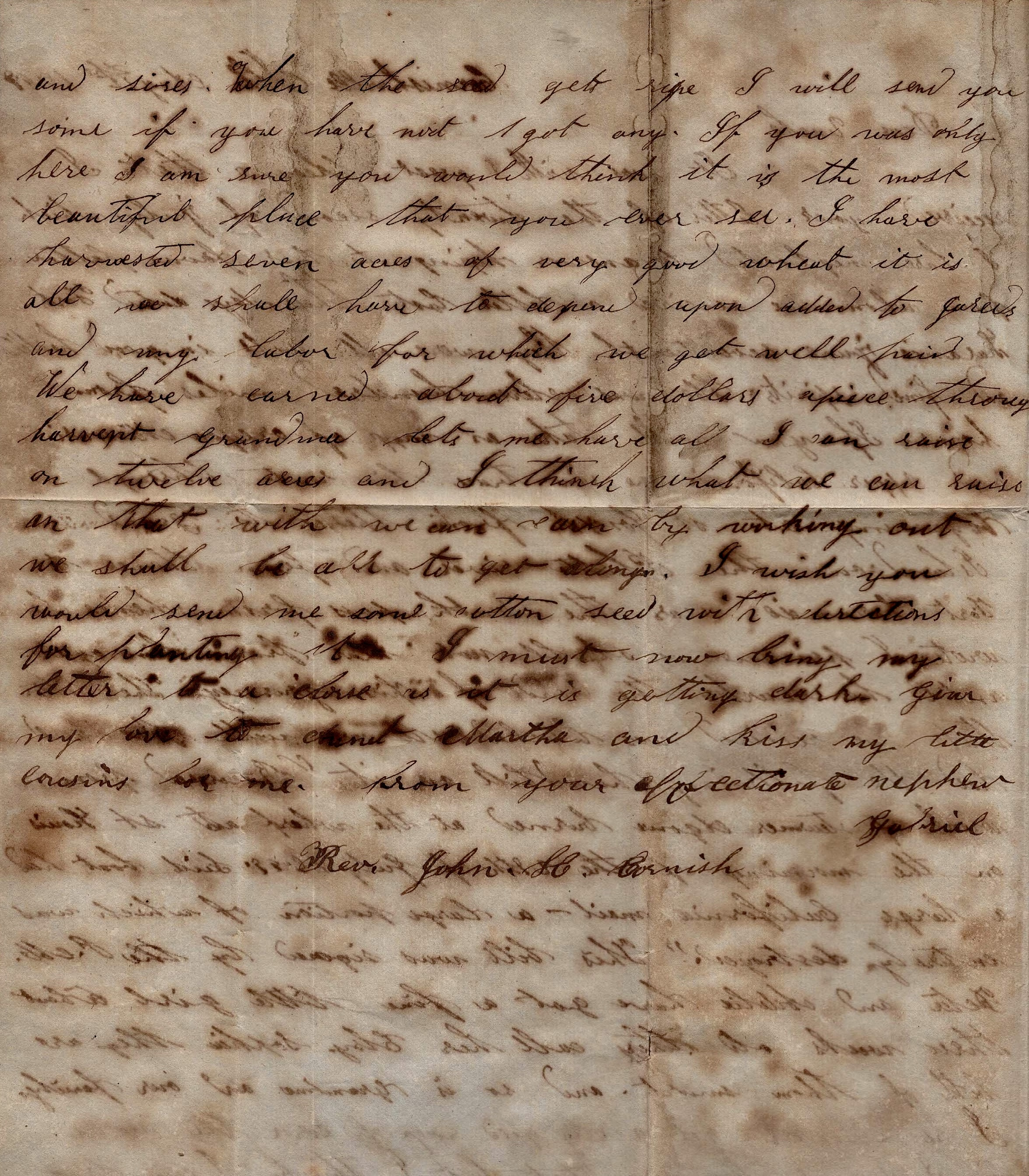

I have harvested seven acres of very good wheat. It is all we shall have to depend upon added to Jareds’ and my labor for which we get well paid. We have earned about five dollars apiece through harvest. Grandma lets me have all I can raise on twelve acres and I think what we can raise on that with [what] we can raise by working out we shall be able to get along. I wish you would send me some cotton seed with directions for planting it.

I must now bring my letter to a close as it is getting dark. Give my love to Aunt Martha and kiss my little cousins for me. From your affectionate nephew, — Gabriel

to Rev. John H. Cornish

1 Newspapers reported a fire on 29 July 1849 at ST. Louis aboard the steamboat Algoma which spread to four others steamers including the San Francisco at the waterfront. “The steamers San Francisco and Algoma, “had just come in loaded from the Missouri river. Their freights consisted of tobacco, hemp, grain, bale rope, bacon, and a variety of produce….A large mail, containing letters from California emigrants, was destroyed on the Algoma, but most of the papers and money on the boat were saved with the exception of $4,000. Two lives were lost, one, Capt. Young of the Algoma, and the other a passenger on the same boat.” It was further reported in the papers that after the fire, “a terrible fracas ensued between the firemen and a party of Irishmen, by whom, it is supposed, the provocation was given. Captain Grant, of the Missouri company, during the melee, received a pistol shot which slightly wounded him—The houses of the Irishmen, which was a resort for boatmen, were then assailed and one of them severely stabbed in several places….The fire and subsequent disturbances, coupled by the recent calamities endured by our city, from the [Cholera] epidemic, and the former sweeping and destructive fire [of May 1849 in which 23 steamboats were destroyed at the wharf and 430 buildings of the city burned] has cast a gloom over all our citizens.” [Source: The Cayuga Chief, 9 August 1849]