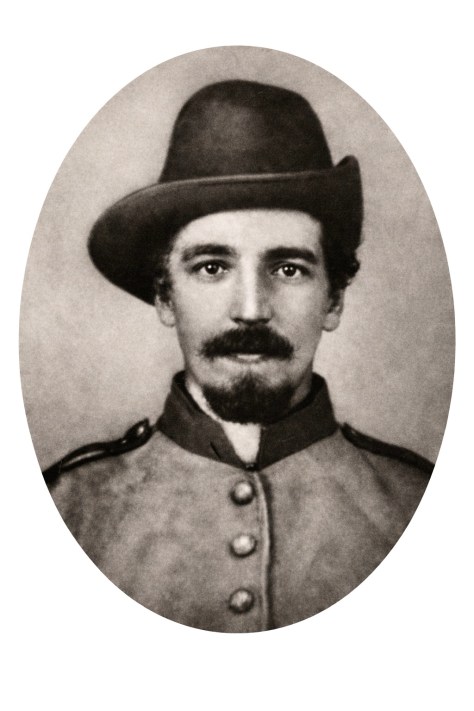

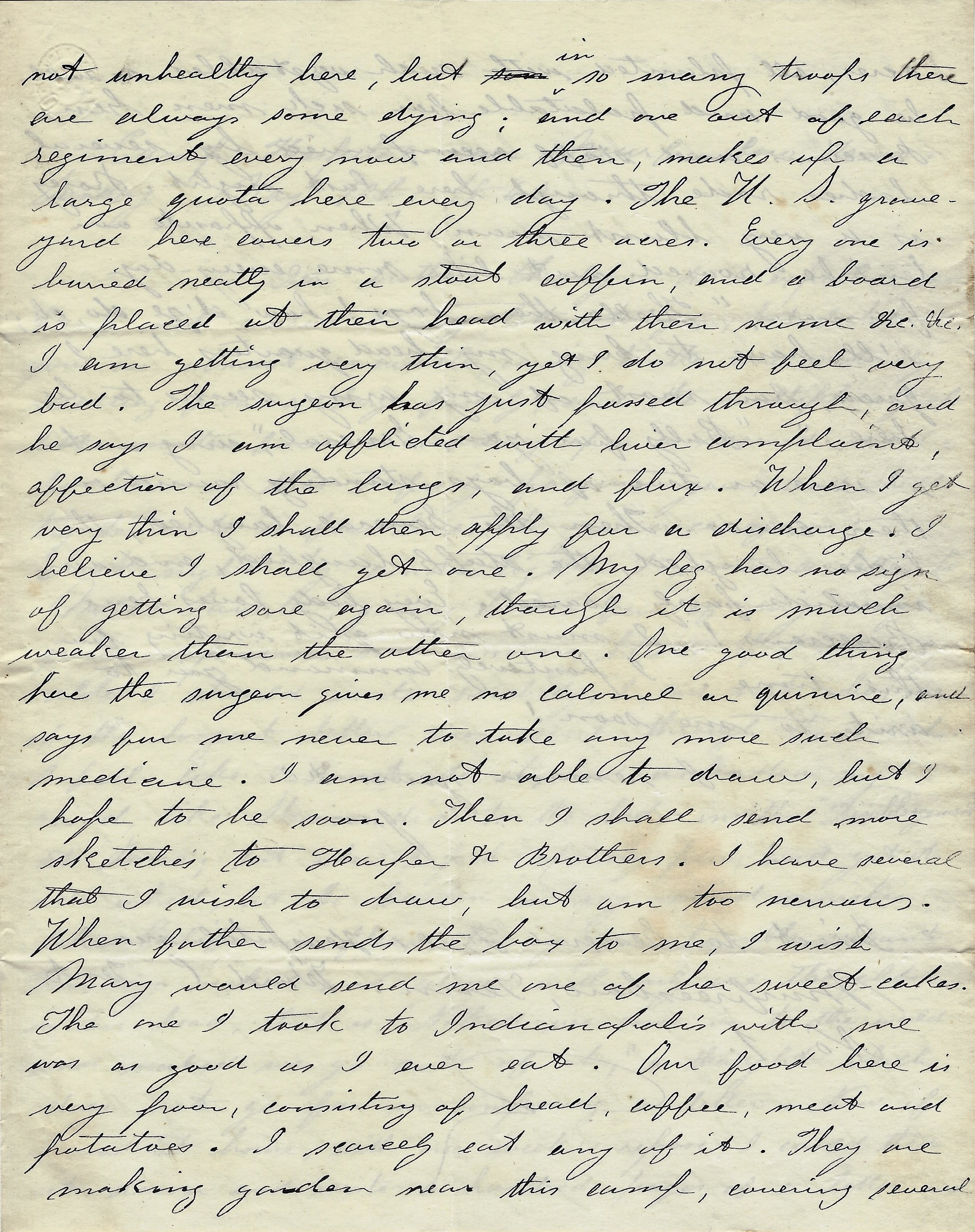

These four letters were written by James Andrew Guirl (1841-1868), the son of Isaac Guirl (1813-1879) and Jane Redick (1813-1888) of Benville, Jennings county, Indiana. In the 1860 US Census, James was enumerated in his parent’s home as a 19 year-old portrait painter. Just prior to his enlistment, James moved to San Jacinto in Jennings county, and while there offered his services in Capt. Michael Gooding’s Co. A of the 22nd Indiana Volunteers in July 1861. He later transferred to Captain David Dailey’s Co. D. Throughout his time in the service, James suffered ill health and a game leg. He was eventually discharged for disability in August 1863. After the war, he moved to Franklin, Venango county, Pennsylvania to visit an uncle and work in the oil fields but again his health failed and her returned to Indiana where he died in 1868.

James had an older brother, William McGowan Guirl (1838-1861), who served in the same company with him but died on 14 December 1861 at Otterville, Cooper county, Missouri.

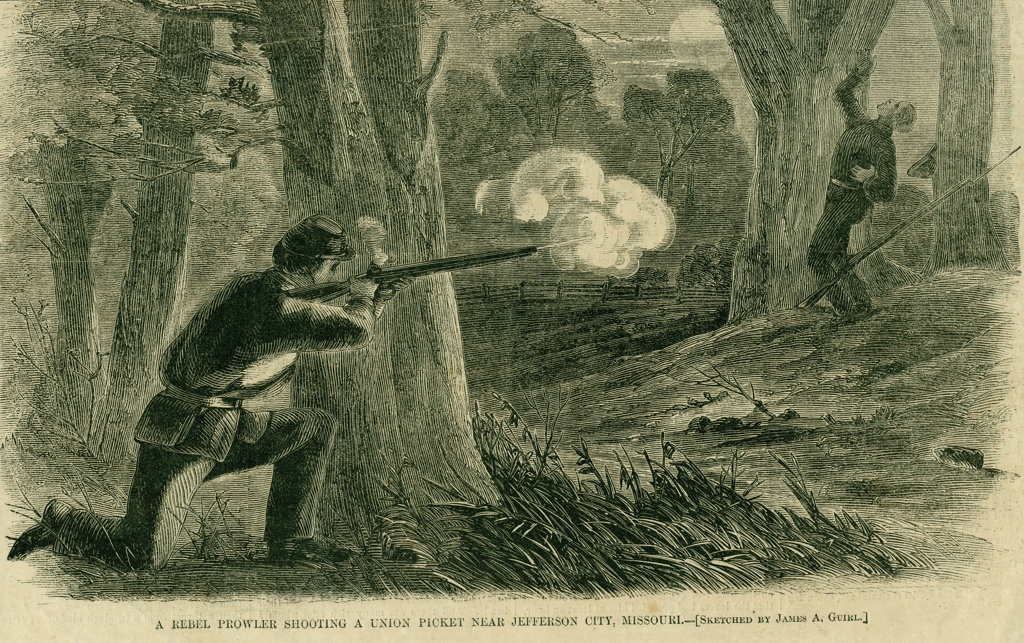

In his letters, James makes several references to his drawings and some of his artistry was indeed utilized by Harpers Magazine. Here is one of his most famous drawings entitled, “A Rebel Prowler Shooting A Union Picket near Jefferson City, Missouri.”

Letter 1

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

April 6th 1863

Dear father and mother,

It seems strange that I now write from this place away down here in the “Sunny South” when only three short weeks ago I wrote to you from the “frozen regions” of Western Pennsylvania. How quick one can fly over this old world of ours now-a-days. In the good old days of yore, when minstrels played from cottage to cottage, when powdered knights and gallant warriors fought for honor and glory, and when it took a man a lifetime to go half way round the world, if they could then have gotten a transient peep into the future and save us at this age, how bewildered they would have been; aye, more, like Sancho Panza when officiating as Governor of the island, they would wish themselves safely out of it, back to the simple and primitive manners of their own period.

I wrote to you from the guard house at Indianapolis on Thursday last and then expected to be severely punished; but that evening I begged our jailor to take me to Gen. [Henry B.] Carrington and let me explain the whole matter. He did so and it proved satisfactory, and that evening at eight I was put under a strict guard with about three hundred others and sent to Louisville. We arrived there at three in the morning and placed in a dismal barracks in the city. There was no fire and we were very cold and uncomfortable all day, and at night we suffered a great deal.

At eight next morning we took the train for Nashville. It was Saturday and a clear, lovely day. When about 80 miles out from Louisville, the train met with a serious acident. A rail gave way over a courfit [?], throwing two cars off the track, one of which rolled over a steep embankment and was totally demolished. It was filled with ladies and children, besides a number of officers returning to their regiments. I was in the other car that ran off but escaped except a sprained shoulder. The sight of the wounded was sickening to behold. A brakeman was completely crushed about the thighs and groin, and was carried to a neighbor’s house insensible. He was in a dangerous position, but instead of jumping off like the other brakeman did, he hung to his post trying to stop the train till he met his fate. One woman with a little child in her lap was bruised from head to foot and almost blinded with her own blood, and when she came to conciousness, she saw her child unhurt sitting, smiling, at the distance of twenty rods. It had been thrown there by the violence of the shock, but alighted unhurt. The woman said it was smiling when the accident took place and it had taken placed so sudden that the child was still smiling when the tragedy was over.

We started on again at two o’clock with 8 or 10 of the wounded in the baggage car, and arrived at Nashville at midnight, We took on a heavy guard of well-armed men at Bowling Green to protect us from the guerrillas who were expected to attack us every moment but we got through in safety. Next morning we took the train to Murfreesboro and about noon I arrived at my old regiment. The boys came from all directions to shake me by the hand and Col. [Michael] Gooding spoke very kindly to me, and this morning elected me as Adjutant’s Clerk. He says that he knew all along that I was unfit for duty but he got word from some of my “friends” on Graham [Creek] that I was as stout as any man in the army, and had boasted as much several times, and he said he then thought I deserved punishment.

Some of the boys say that I was discharged long ago but I can’t tell how it is. I am now writing in the Adjutant’s office, and feel very happy and contented. I want you to thank Joe Passmore for me as he was the sole cause of my returning to honor and duty. Being so long sick in the hospital, I have had ever since a untold honor of the army. But now I am all right again.

George Thomas is unwell at the convalescent camp and Jack Haynes is well and hearty. Poor fellow—his hair is far more gray than when I saw him last, but his great warm heart is just as it always was. I am very unwell, but the surgeon says he will get me well in a few days. I got a desperate cold at Louisville and can scarcely speak above a whisper. It has settled on my lungsm but the mild climate here I hope will prove a cure for me. I feel so confused that I can write no more today. I have jumbled together all that I have written so that I expect you will all laugh at it. Send all letters to me as follows:

James A. Guirl, Co. D, 22nd Regt. Indiana Volunteers, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in care of Captain [David] Dailey.

Write soon. Yours, — Jim

Letter 2

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Monday, May 3rd 1863

Dear Father and Mother,

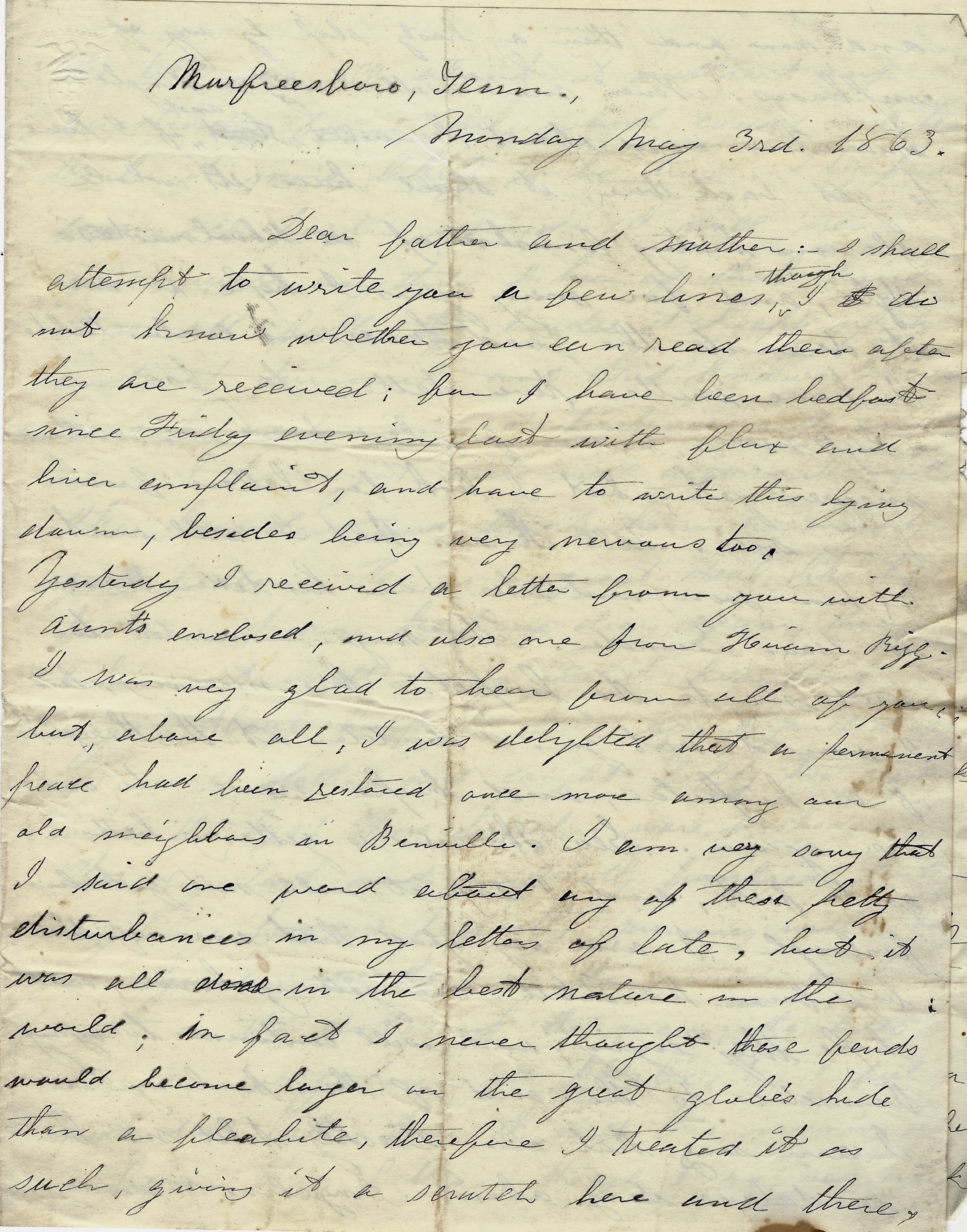

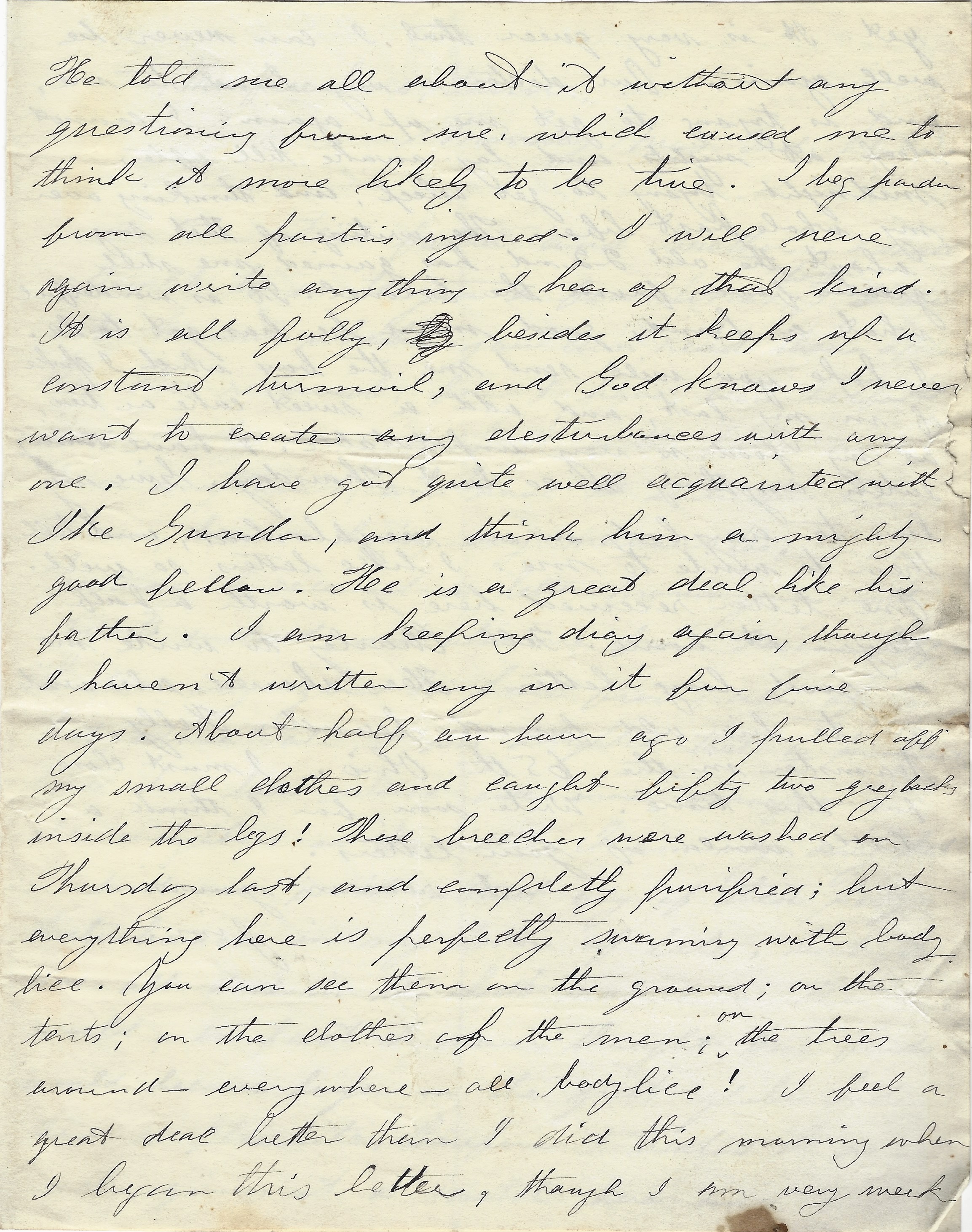

I shall attempt to write you a few lines though I do not know whether you can read them after they are received for I have been bedfast since Friday evening last with flux and liver complaint, and have to write this lying down, besides being very nervous too.

Yesterday I received a letter from you with Aunt’s enclosed, and also one from Hiram Bigg. I was very glad to hear from all of you but, above all, I was delighted that a permanent peace had been restored once more among our old neighbors in Benville. I am very sorry that I said one word about any of these petty disturbances in my letters of late. But it was all done in the best nature in the world. In fact, I never thought those feuds would become larger in the great globe’s hide than a flea bite. Therefore, I treated it as such, giving it a scratch here and there, and now and then a hasty slap by way of emphasis. Never more will I say a single uncourteous word about Benville and if I live to get back there, it shall have its whole glorious history finished up un schoolmaster’s style, and for many years I hope to see it decorate the good Governor’s enter table. I have written two letters to Joe Passmore, neither of which have met with an answer yet, but I look for letters from him soon.

Tell Hiram that I will write to him soon, and also show his letter to Isaac Gunder.

The surgeon wanted to send me to the hospital this morning, but I would not go. I shudder at the thoughts of a hospital, and hope never to enter one again. George Thomas is getting better quite fast, and I expect will not get his furlough. I am very glad that some of the boys from the 26th [Indiana] are getting home and hope they enjoy—and will continue to enjoy—themselves to the end of their furloughs.

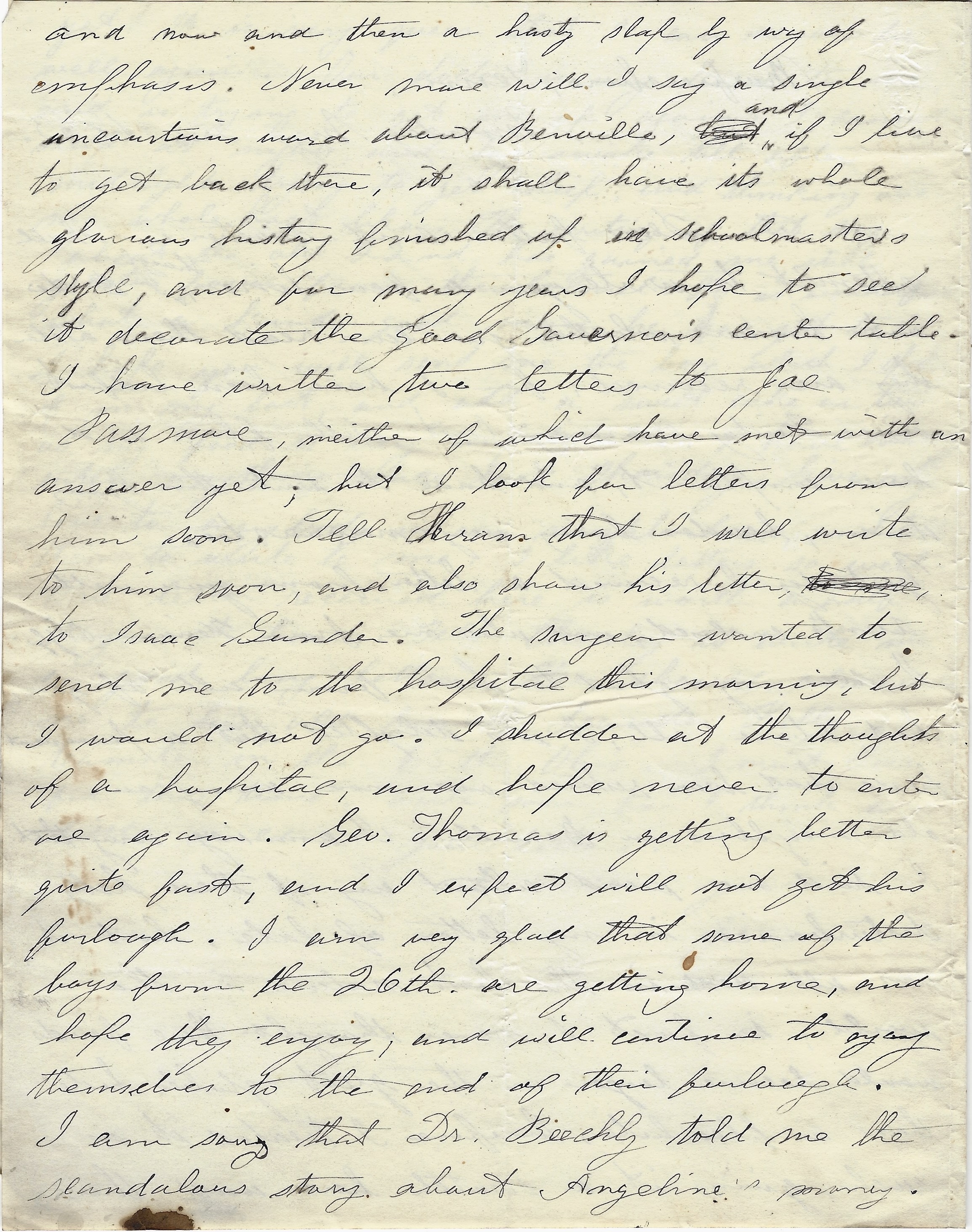

I am sorry that Dr. [Nathaniel J.] Beachley 1 told me the scandalous story about Angeline’s money. He told me all about it without any questioning from me which caused me to think it more likely to be true. I beg pardon from all parties injured. I will never again write anything I hear of that kind. It is all folly. Besides, it keeps up a constant turmoil, and God knows I never want to create any disturbances with anyone.

I have not got quite well acquainted with Ike Gunder and think him a mighty good fellow. He is a great deal like his father. I am keeping a diary again though I haven’t written any in it for five days. About half an hour ago I pulled off my small clothes and caight fifty-two greybacks [lice] inside the legs! These breeches were washed on Thursday last, and completely purified, but everything here is perfectly swimming with body lice. You can see them on the ground, on the tents, on the clothes of the men, on the trees around—everywhere—all body lice!

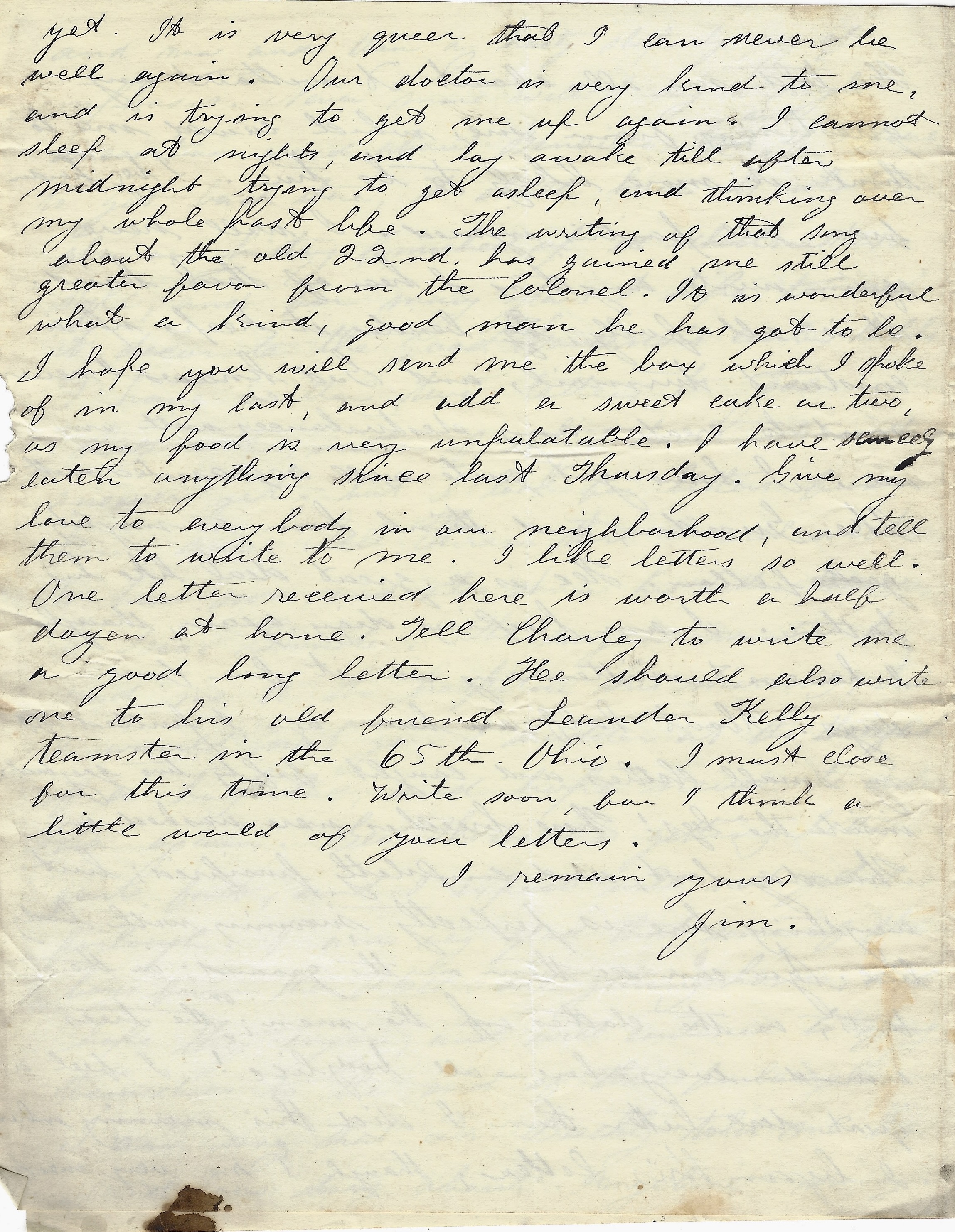

I feel a great deal better than I did this morning when I began this letter though I am very weak yet. It is very queer that I can never be well again. Our doctor is very kind to me and is trying to get me up again. I cannot sleep at nights and lay awake till after midnight trying to get asleep and thinking over my whole past life.

The writing of that song about the Old 22nd has gained me still greater favor from the Colonel [Michael Gooding]. It is wonderful what a kind, good man he has got to be. 2

I hope you will send me the box which I spoke of in my last and add a sweet cake or two as my food is very unpalatable. I have scarcely eaten anything since last Thursday. Give my love to everybody in our neighborhood and tell them to write to me. I like letters so well. One letter received here is worth a half dozen at home. Tell Charley to write me a good long letter. He should also write one to his old friend Leander Kelly, teamster in the 65th Ohio.

I must close for this time. Write soon for I think a little world of your letters. I remain yours, — Jim

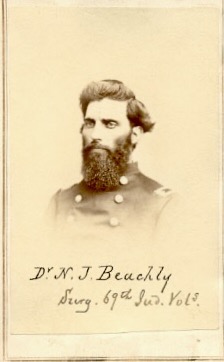

1 Nathaniel Jacob Beachley (1831-1908), a native of Somerset county, Pennsylvania, and a graduate of the Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia who was practicing medicine in Vernon, Jennings county, Indiana, when the Civil War began in 1861. In the first year of the war he organized Co. H, 26th Indiana Volunteers and served with that company until mustering out on 24 February 1863 to accept a commission as Assistant Surgeon of the 22nd Indiana Volunteers. In April 1864, he was commissioned Major Surgeon of the 69th Indiana Volunteers. See 1861-64: Nathaniel Jacob Beachley to George Washington Shober.

2 James must have written the lyrics of a song (“The Old 22nd”) dedicated to the 22nd Indiana Infantry that no doubt praised the Colonel of the regiment, but I have not been able to find a copy.

Letter 3

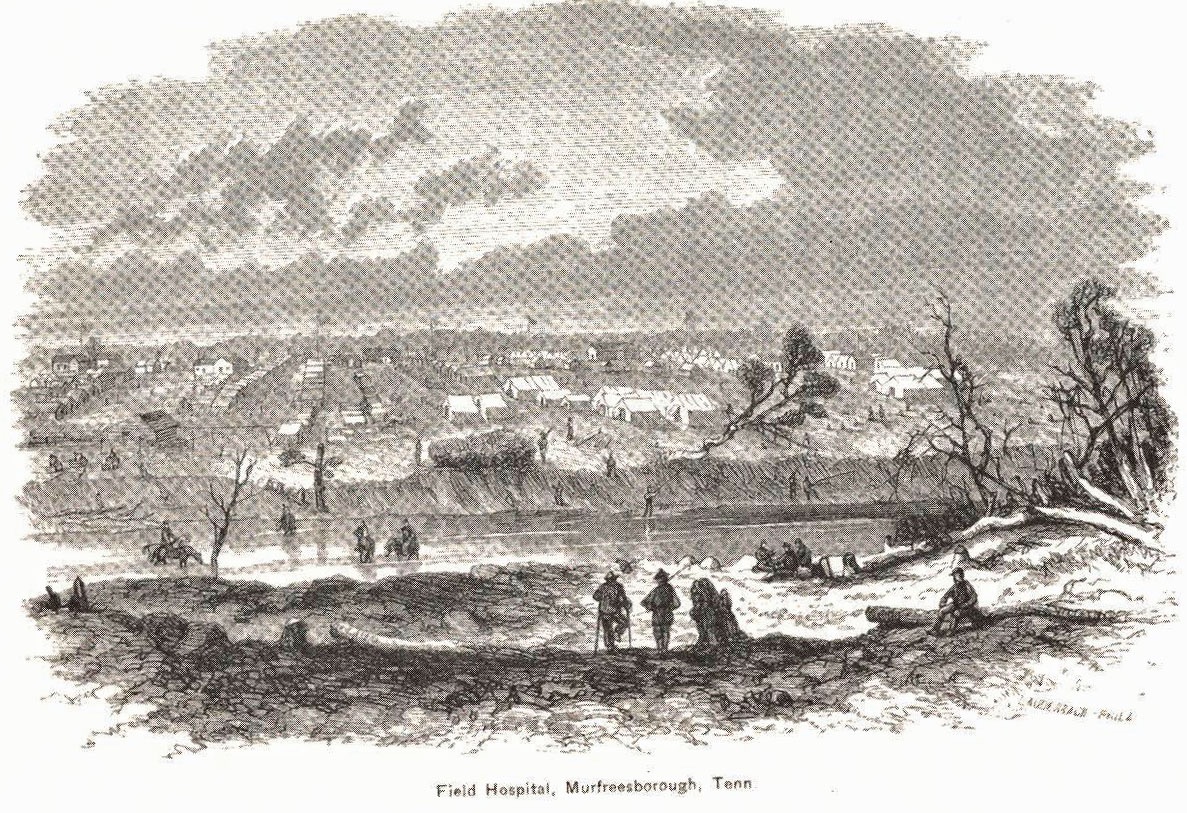

Camp Hospital near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Sunday, May 10th 1863

Dear brother Charley,

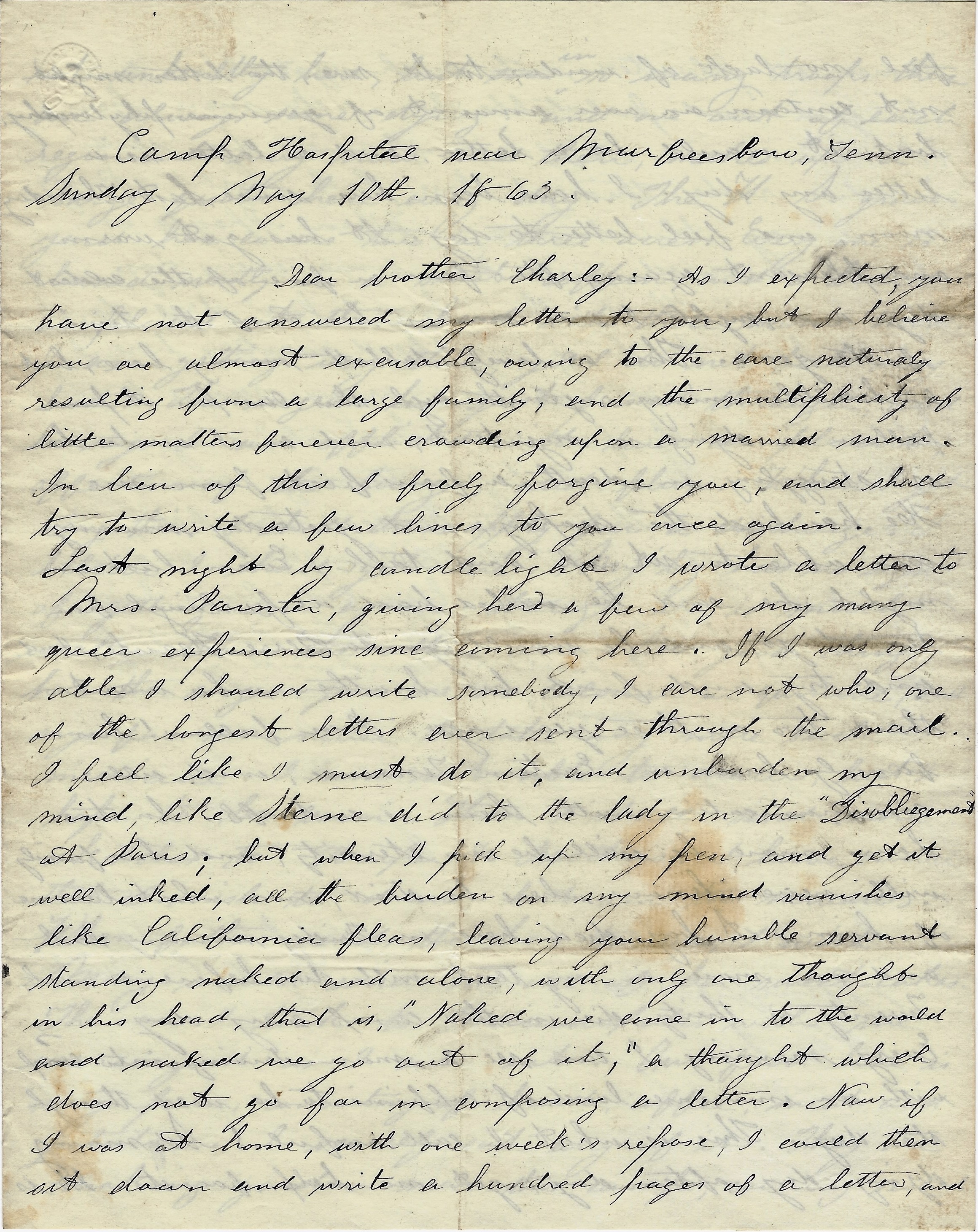

As I expected you have not answered my letter to you but I believe you are almost excusable owing to the care naturally resulting from a large family, and the multiplicity of little matters forever crowding upon a married man, In lieu of this, I freely forgive you and shall try to write a few lines to you once again.

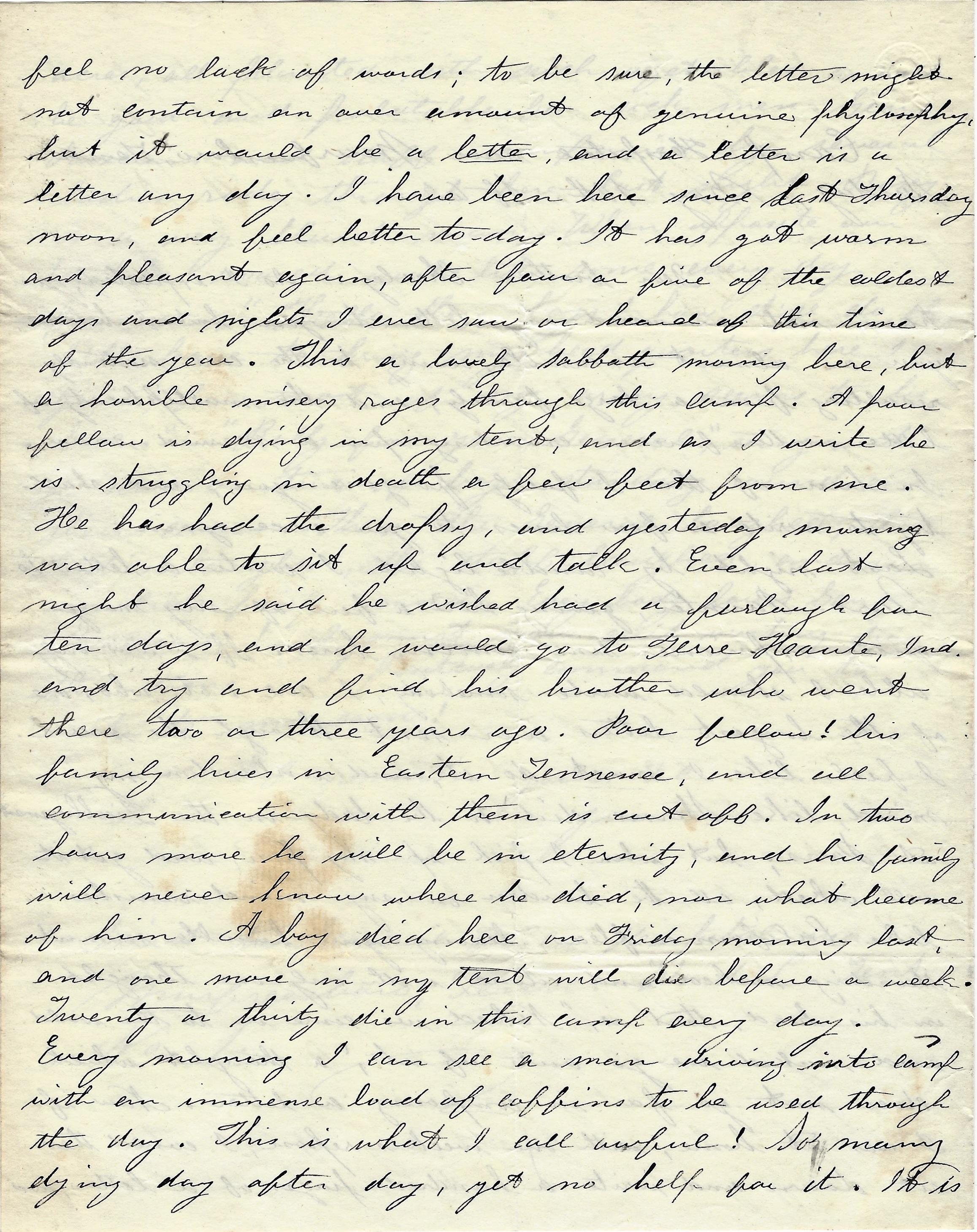

Last night by candlelight I wrote a letter to Mrs. Painter giving her a few of my many queer experiences since coming here. If I was only able I should write somebody, I care not who, one of the longest letters ever sent through the mail. I feel like I must do it, and unburden my mind, like Sterne did to the lady in the “Disobligement” at Paris. But when I pick up my pen and get it well inked, all the burden on my mind vanishes like California fleas, leaving your humble servant standing naked and alone, with only one thought in his head—that is, “Naked we come in to the world and naked we go out of it,”—a thought which does not go far in composing a letter. Now if I was at home with one week’s repose, I could then sit down and write a hundred pages of a letter and feel no lack of words. To be sure, the letter might not contain an over amount of genuine philosophy, but it would be a letter, and a letter is a letter any day.

I have been here since last Thursday noon, and feel better today. It has got warm and pleasant again, after four or five of the coldest days and nights I ever saw or heard of this time of the year. This is a lovely Sabbath morning here but a horrible misery rages through the camp. A poor fellow is dying in my tent and as I write, he is struggling in death a few feet from me. He has had the dropsy, and yesterday morning was able to sit up and talk. Even last night he said he wished he had a furlough for ten days and he would go to Terre Haute, Indiana, and try and find his brother who went there two or three years ago. Poor fellow! his family lives in Eastern Tennessee and all communication with them is cut off. In two hours more, he will be in eternity, and his family will never know where he died, nor what became of him.

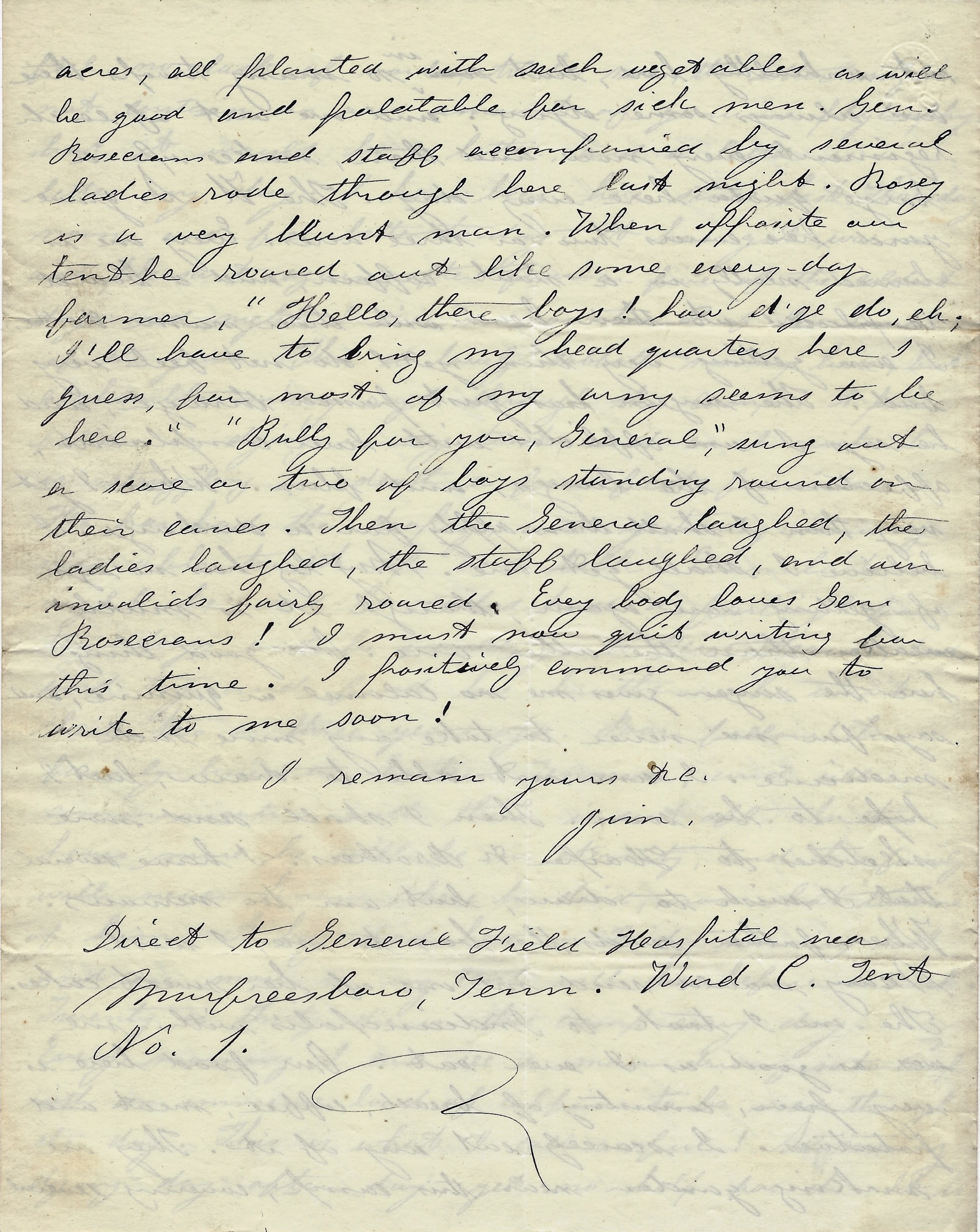

A boy died here on Friday morning last and one more in my tent will die before a week. Twenty or thirty die in this camp every day. Every morning I can see a man driving into camp with an immense load of coffins to be used through the day. This is what I call awful! So many dying day after day, yet no help for it. It is not unhealthy here but in so many troops, there are always some dying, and one out of each regiment every now and then makes up a large quota here every day.

The U. S. graveyard here covers two or three acres. Everyone is buried neatly in a stout coffin and a board is placed at their head with their name, &c. &c. I am getting very thin, yet I do not feel very bad. The surgeon has just passed through and he says I am afflicted with liver complaint, affection of the lungs, and flux. When I get very thin, I shall then apply for a discharge. I believe I shall get one. My leg has no sign of getting sore again though it is much weaker than the other one. One good thing here, the surgeon gives me no calomel or quinine and says for me never to take any more such medicine.

I am not able to draw but I hope to be soon. Then I shall send more sketches to Harper & Brothers. I have several that I wish to draw, but I am too nervous.

When father sends the box to me, I wish Mary would send me one of her sweet cakes. The one I took to Indianapolis with me was as good as I ever eat. Our food here is very poor, consisting of bread, coffee, meat and potatoes. I scarcely eat any of it. They are making garden near this camp, covering several acres, all planted with such vegetables as will be good and palatable for sick men.

Gen. Rosecrans and staff accompanied by several ladies rode through here [at the hospital camp] last night. Rosey is a very blunt man. When opposite our tent he roared out like some every-day farmer, “Hello there boys! how d’ye do, eh? I’ll have to bring my headquarters here, I guess, for most of my army seems to be here.”

“Bully for you, General!” sung out a score or two of boys standing round on their canes. Then the General laughed, the ladies laughed, the staff laughed, and our invalids fairly roared. Everybody loves Gen. Rosecrans!

I must now quit writing for this time. I positively command you to write to me soon! I remain yours, &c. — Jim

Direct to General Field Hospital, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Ward C, Tent No. 1.

Letter 4

General Field Hospital near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

May 22nd 1863

My dear Father and Mother,

Your letter of the 18th arrived yesterday evening and I should have answered it immediately had I been able, but then I felt worse than usual and was confined to my bed. This morning I was still worse but now (three o’clock p.m.), I am able to sit up and write. A few days ago I was able to ride to the 22nd Regiment and get my Descriptive List and Pay Roll so that I can draw my pay here. Thanks to the kindness of Jack Haynes, who is now orderly of Co. D, for procuring me the necessary papers, as my Captain and Lieutenants were all too lazy and indifferent to make them out though they knew that I had come most a mile through a severe illness to procure them. How infernally mean are some of the officers of the 22nd Regiment! While at camp I received two letters but neither from Benville.

I came back late in the evening, weak, sick, and exhausted. I had almost given up the idea of ever receiving any more letters from you. It seems so very long since I came to this place. I have some of the best of friends here and most of them were brought round by my drawings and kindness to my fellow sick. The young lady who brings us our delicacies after the meals each day never fails to give me a goodly portion and then follows a pleasant chit chat of a minute or two, which, I assure you, is very agreeably maneuvered by us so as to interest all in the tent.

The doctor is also interested in me and my drawings and the result may bethat I may get a discharge sometime; but God only knows when. Several have been discharged since my arrival here, but they were men entirely ruined and who will die on the way home, or shortly after reaching there. When I first returned to my regiment, I thought that I would have refused a discharge had they offered me one; but now I plainly see that I cannot stand army service of any kind. Lying on the ground, drinking strange water, eating hard and worse food, and all the time laboring under a kind of excitement from the multiplicity of strange things constantly taking place in a great army is more than I can undergo.

How thankful and doubly thankful I was when I learned that you had started a box of eatables to me. I have no appetite, but I know I can eat something that comes from the hands of my mother and sister! I only hope that you will not think me a son who is far more trouble to his parents than he is worth. I know I have always been a poor, needy wretch, forever unfortunate, yet sometimes one of the happiest fellows alive. When I look back at the golden times when I built miniature railways round our pleasant cottage, when I sauntered along to the Old Quaker School on the hill on bright spring and summer mornings, and when I greedily looked for books in the library at San Jacinto and proudly carried my selection home to be perused with untold joy—then a dizziness seems to grow over me, and in spite of all my efforts, tears will come into my eyes, and a foreboding that such times are gone forever come into my soul never to be effaced.

I am a queer, queer fellow. No one can read me in a day or even a year. No man but Dr. Davidson of Madison ever got a complete confession of thoughts from me. That outpouring was like a fairy view of Heaven to me, It was joy of the purest kind. I shall never forget what he told me on separating at DuPont on the day I took him home from brother Charley’s. “You are poor now,” he said, taking my hand, “but before you die, you will be the coveted companion of the greatest men!”

I thought of this for a long time, and tried to imagine myself at some future day a “hale old fellow with silver hair” surrounded by opulence and wealth, with a name equal to that of the great painter Raphael. The doctor had built a dangerous castle in the air for me, and I was constantly adding and enlarging its beauty. Next I would see myself a great author—a perfect literary lion, with the whole world enraptured with my works. How much larger was my castle then! How gloriously it shone down through th mystic clouds and vapors of time! It has all faded and disappeared now. I am left standing on a barren shore, made tenfold more desolate by the remembrance of the golden structures which once hovered around and above me. My only hope now, like Irving’s Poor-Devil-Author, is to be a common village portrait painter, or maybe half an author for frivolous magazines. Is not the just and sober reality of the future of my life? But enough of this.

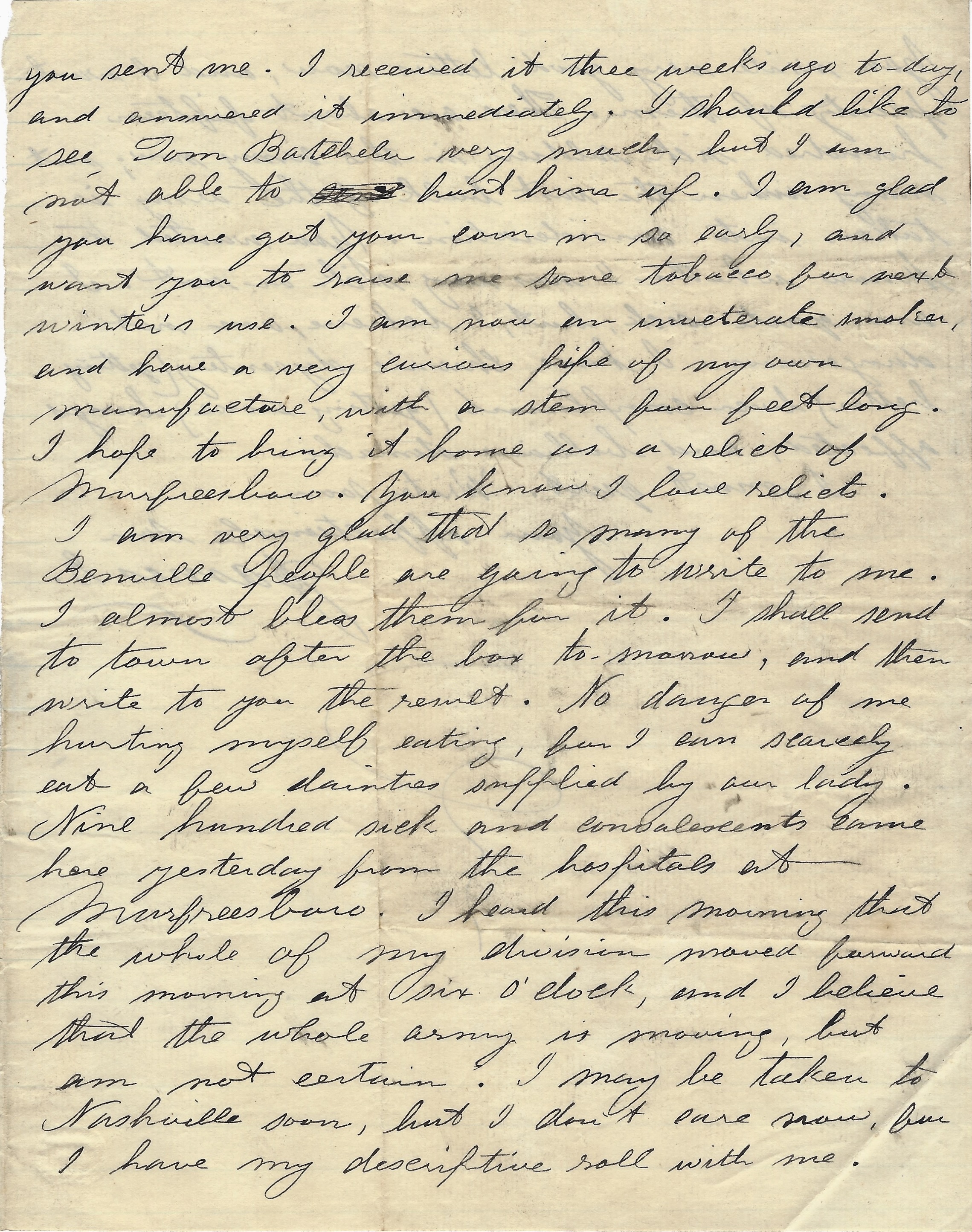

I have received Hannah Bigg’s letter which you sent me. I received it three weeks ago today and answered it immediately. I should like to see Tom Batcheler very much but I am not able to hunt him up. I am glad you have got your corn in so early and want you to raise me some tobacco for next winter’s use. I am now ab inveterate smoker and have a very curious pipe of my own manufacture with a stem four feet long. I hope to bring it home as relic of Murfreesboro. You know I love relics.

I am very glad that so many of the Benville people are going to write to me. I almost bless them for it. I shall send to town after the box tomorrow and then write to you the result. No danger of me hurting myself eating for I can scarcely eat a few dainties supplied by our lady. Nine hundred sick and convalescents came here yesterday from the hospitals at Murfreesboro. I heard this morning that the whole of my division moved forward this morning at six o’clock and I believe that the whole army is moving, but am not certain. I may be taken to Nashville soon, but I don’t care now, for I have my Descriptive Roll with me.

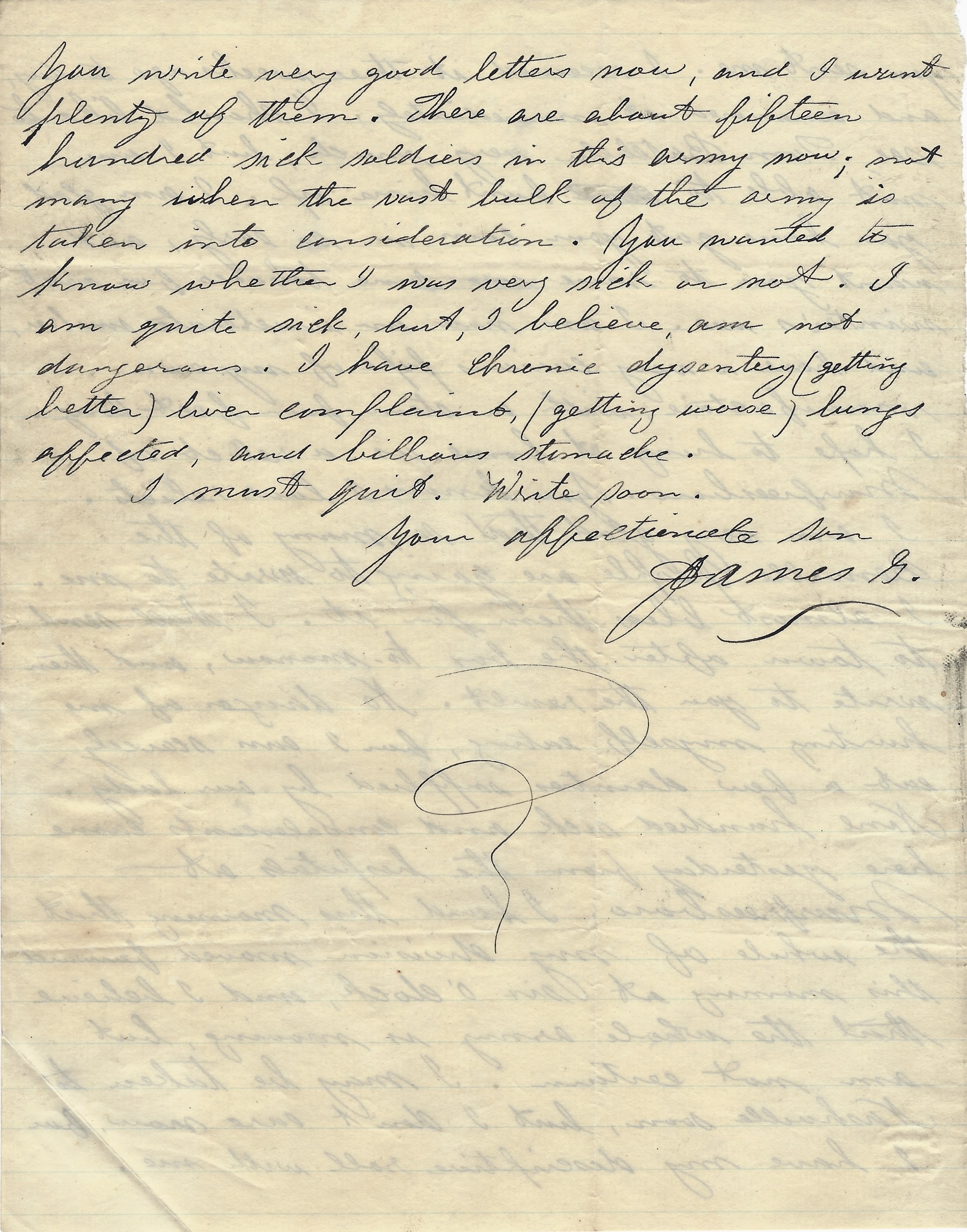

You write very good letters now and I want plenty of them. There are about fifteen hundred sick soldiers in this army now; not may when the vast bulk of the army is taken into consideration. You wanted to know whether I was very sick or not. I am quite sick but I believe am not dangerous. I have chronic dysentery (getting better), liver complaint (getting worse), lungs affected, and billious stomach. I must quit. Write soon.

You affectionate son, — James G.