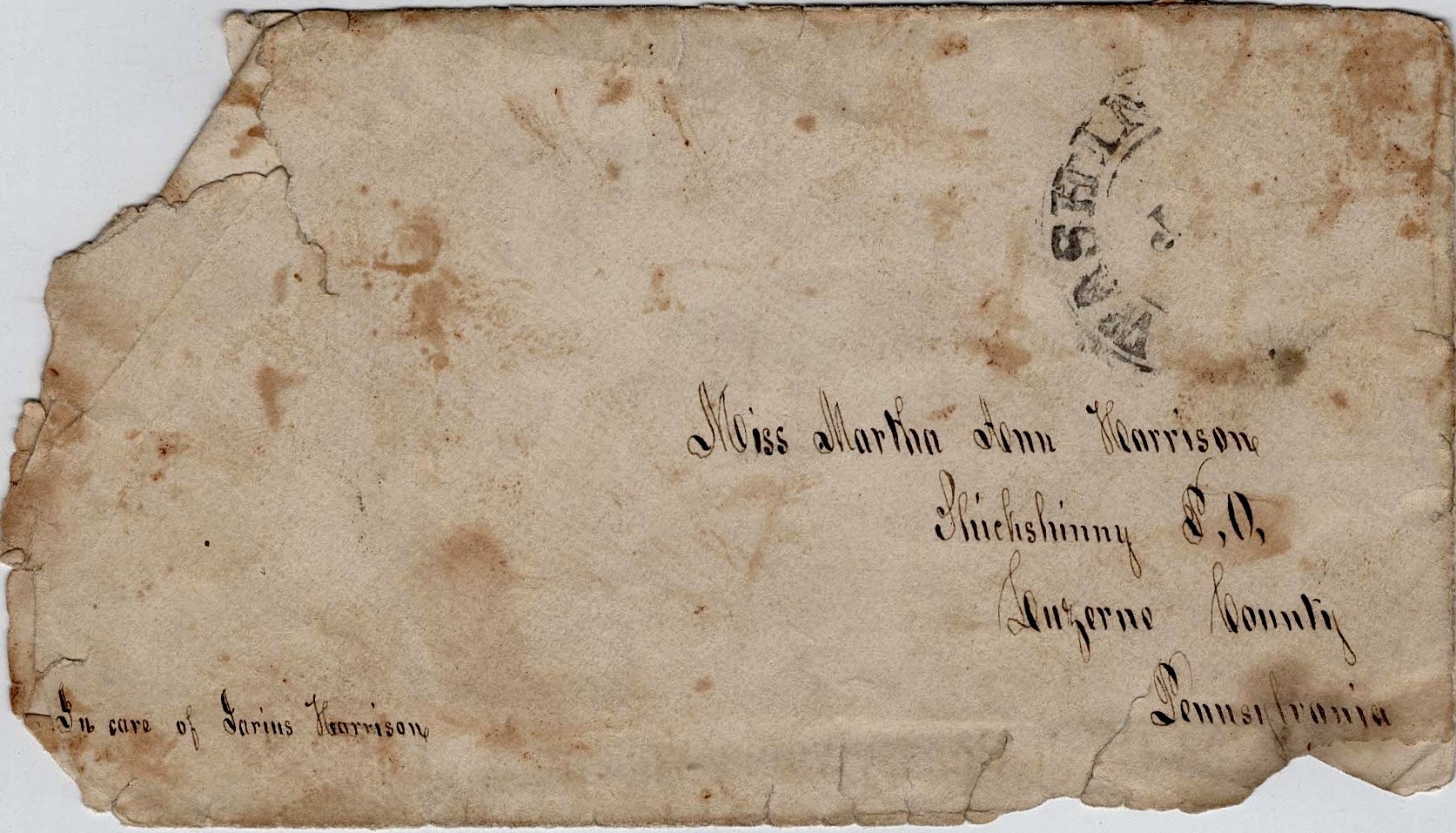

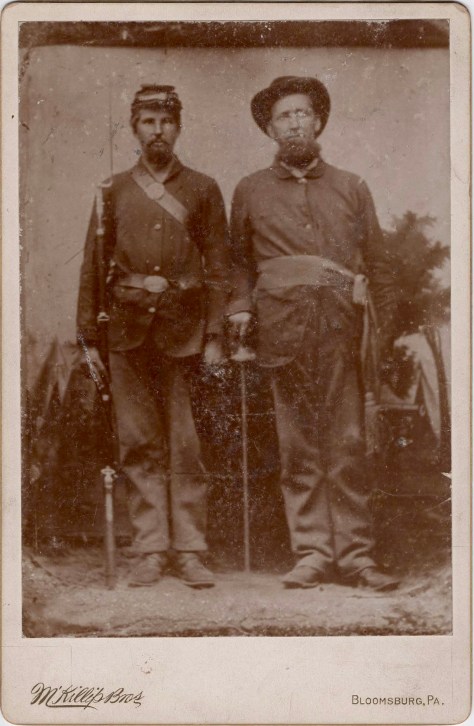

The following letters were written by Jesse Harrison (1818-1863), the son of Stephen Harrison, Jr. (1777-1865) and Mary Dodson (1779-1859). He was married to Phoebe Tubbs (1818-1881) and was the father of five children prior to his entering into the service. His children were Daniel W. Harrison (1839-1901), Antrim Byrd (“Brice” or “Bird”) Harrison (1842-1893), Mary Elizabeth Harrison (1844-1935), Martha Ann Harrison (1846-1927), and Samuel Herbert (“Herb”) Harrison (1846-1931).

Jesse was 44 years old when he enlisted on 20 September 1862 to serve three years in Co. I, 143rd Pennsylvania Infantry. He was mustered in as 1st Sergeant on 18 October 1862 under the command of Col. Edmund L. Dana. He remained with his company until he was mortally wounded in the 1st day’s fighting at Gettysburg. He died at Camp Letterman—the field hospital set up near Gettysburg—on 20 August 1863 from the wound of his shattered right thigh. His 19 year-old daughter Mary came to the camp hospital to care for her father but could not save him. Her letter to her mother is the last letter in this collection. Curiously, Mary mentions having become acquainted with Julia Culp of Gettysburg fame while staying in Gettysburg in the weeks following the battle.

Letter 1

[Editor’s Note: The 143rd Pennsylvania Infantry was organized at Wilkes-Barre in October 1862 and left Pennsylvania for Washington, D.C. in November 7th. They served duty in the defenses of that city until January 17, 1863 when they were ordered to join the Army of the Potomac in the field January 1863 following the Battle of Fredericksburg.]

Camp Slocum [northern defenses of Washington D. C.]

November 30, 1862

My dear friends, wife, children, father and all,

It is Sabbath morn and very pleasant though it was very cold through the night that is past and gone. Yet we fared tolerable well considering all things. And having performed the duties of the morning, I have seated myself by the side of a board to write a few of my unconnected thoughts to you that you may know of my welfare, my whereabouts &c. &c.

And to commence, I am well—perfectly well, never having enjoyed better health in my life. And our Boys are generally well though some of them complain of colds and I often wonder that we are not all sick, or where sickness never comes. But we have been wonderfully preserved for which we should have been wonderfully preserved for which we should be more thankful than we are. Yet I do try to remember from where the many blessings arise which I enjoy from day to day and from time to time and although many complain of the exposure and hardships to which our regiment has been subject (for which no one can blame them), yet I try to look on the bright side of the picture and to be content with my lot. And I do hope this may find you all enjoying the greatest of blessings—viz, health, prosperity, and contented minds, which rightly appreciated are continual feasts.

I promised to write to Mary some days ago but have not had time untill today and today I am hurried and interrupted so much and often that I shall not be able to write anything interesting for which you must excuse me this time.

I received your kind and thrice letters in due time and there is no use of my telling you that I was pleased and that I would like to answer each one separate and singly, but have not time at present. Perhaps in a few days I may be differently situated and have more time. Then look out, though I think I have done pretty well—at least better than you could expect of me.

Yesterday for the first time since we left Virginia I went out of our camp to visit the Boys who lie in the hospitals in and around the City of Washington. Charles Wm. Betzenberger, a very worthy young man, sergeant of our company, and I left about half past 7 a.m. and in one hour we were in the City, when having to get some blank certificates struck (one of which I enclose) and our motto being business first and then pleasure, we found a printing office and go the blanks, then went to Armory Square in which are encamped the company enlisted under Capt. [Edmund Osborne [Co. F, 149th Pennsylvania]. I soon met Charles Wilson, Wm. & Ezra Zimmer and many others of my acquaintance. Weston [D.] Millard in particular I would mention as he looks remarkably well and appears to enjoy himself well as do all who are reported for duty. They number 56 at present. I stayed a few minutes with them and then Charles Wilson and I left for Emory Hospital to see D. K. Harrison [56th Pennsylvania], some two miles distant where we soon arrived when the surgeon told us that he had just gone to the City. About march was the word and back we came to the camp [of the 149th Penn] which is situated near the centre of the City, only a short distance from the Capitol.

Dinner being ready, I dined with the Boys in Charles Wilson’s tent. Had good fare. I then went to the Armory Hospital where I found Caleb McCafferty. Though not looking very well, yet he thinks that he is improving. Dr. Culver was there also and looks very bad. I then returned to quarters and found [Sergt.] D[aniel] K. Harrison and I don’t have to guess that I was pleased. I was confident of the fact, and if appearances indicate anything he was equally gratified. We were together some two hours during which you may rest assured there was some talking done. He looks very well and expects to go to his regiment this week. He says [our son] D. W. [Daniel W. Harrison, 56th Penn.] was all right when he left but how the poor boy is by this time we know not. Many skirmishes have taken place since he left. I have written to him but have received no answer. If you hear from him, let me know immediately.

At 3 o’clock we parted regretting very much the shortness of the time but such is the life of a soldier—we meet to part, and often to meet no more on Earth. May my God grant that we all may meet in heaven. My friend, Milton Laycock and I then went to the Mount Pleasant Hospital, visited Isaac Tubbs who talks of joining his regiment this week. I took supper with him, about 1,000 of us sitting at one table, the most of whom were unfit for duty. We then returned to our camp. If I had room and time I could write all night but I have neither and consequently must come to a close by subscribing myself your dutiful son, husband, father, brother & friend. The enclosed certificate is for mother. The $100 for Bird. The $20 for Herb. The two Bills cost me five cents.

I had not told you that a man by the name of [George] Platt of our regiment died last Friday night in the hospital. He was much thought of in his company [Co. C].

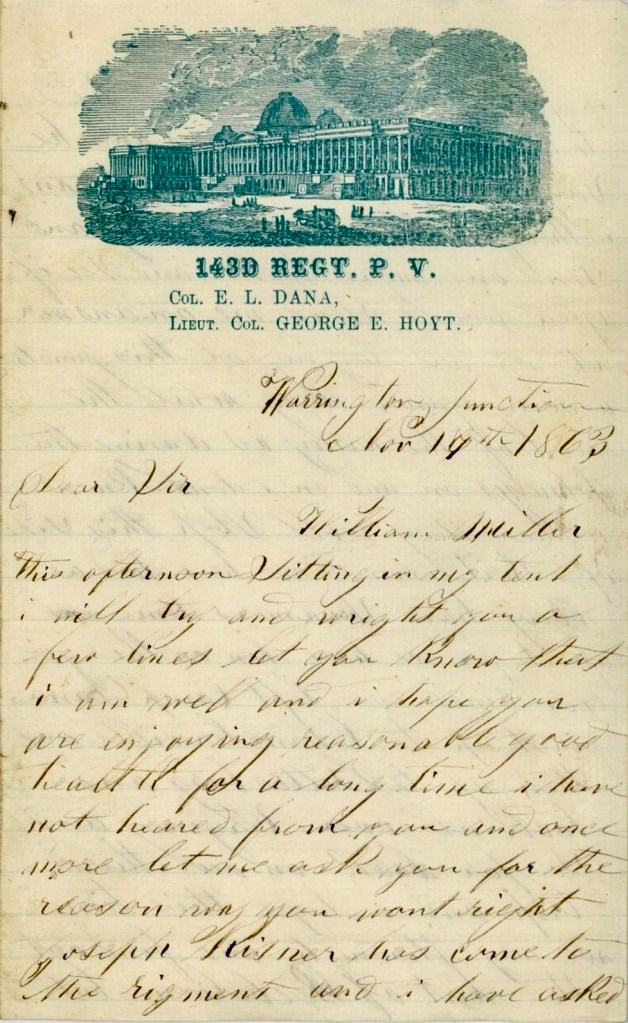

Letter 2

Camp near Fort Slocum

December 5th 1862

My Dear Mary,

Having promised in Frank’s letter of last evening to write an answer to your blessed, kind letter of the 29th ult., I embrace the present opportunity for so doing. And once more, through the mercy of Divine Providence, I can say that I am well and I do sincerely hope this may find you all enjoying the greatest of blessings conferred upon us while in this world. You stated in yours that it was storming. Also that you were all busy. If I could have dropped in just one moment I think we could have had a good time. Don’t you? But that privilege is denied me and I have to be content, though I may disappoint you some of these days and drop in before you are aware. Then we will have a time, won’t we, eating buckwheat cakes & sausage.

You stated that you expected visitors. I received a letter from one of them last night—Sylvina K. She wrote that whe was much pleased with her visit. I answered her letter today. You spoke about your bonnets, the price, &c. Get those that suits you. Otherwise go bare-headed. Don’t stint yourselves in anything though it stands us all in hand to be economical. You ask about Wesley Hoyt. He has seen some hard times with the rest of us but has lived through. He was in this morning and looks very well. The guard house knows him well.

In regard to the beef cattle, I think with father’s consent, they had better be sold if it can be done to advantage. Tell Bird to consult with Hat about it and submit to father’s decision. You say that father has a great deal of trouble about Dan and I. You must take my place. Be all the comfort you can to him. Counsel with the boys and have them try to please him. He will not expect anything unreasonable of any of you. He never has of me and I have lived with him longer than you have. Tell him that I seen Ezekiel’s Dan, that he had week in the hospital on account of rheumatism, but is better now. He says our Dan is fat as a pig, that he enjoys himself well, and that he has a situation as Provost Guard, and consequently is not exposed as much as he used to be.

Frank Koons has not got back yet. Where is he? And where is Will Monroe? Write and tell me everything that I want to know. You can guess some. Tell Bird to keep his fingers in his pocket and he would not get them marked. If you had let me known in time, I would have tried to come up and helped you to eat that Rib. But so it is. I am always behind though I have the advantage in one thing—the coffee line. I don’t have to drink shuck, but have good strong coffee three times a day with plenty of good sugar. Ain’t that Bully. Our company draws more than they can use and we have towards a hundred pound on hand. Don’t you wish you had some of it?

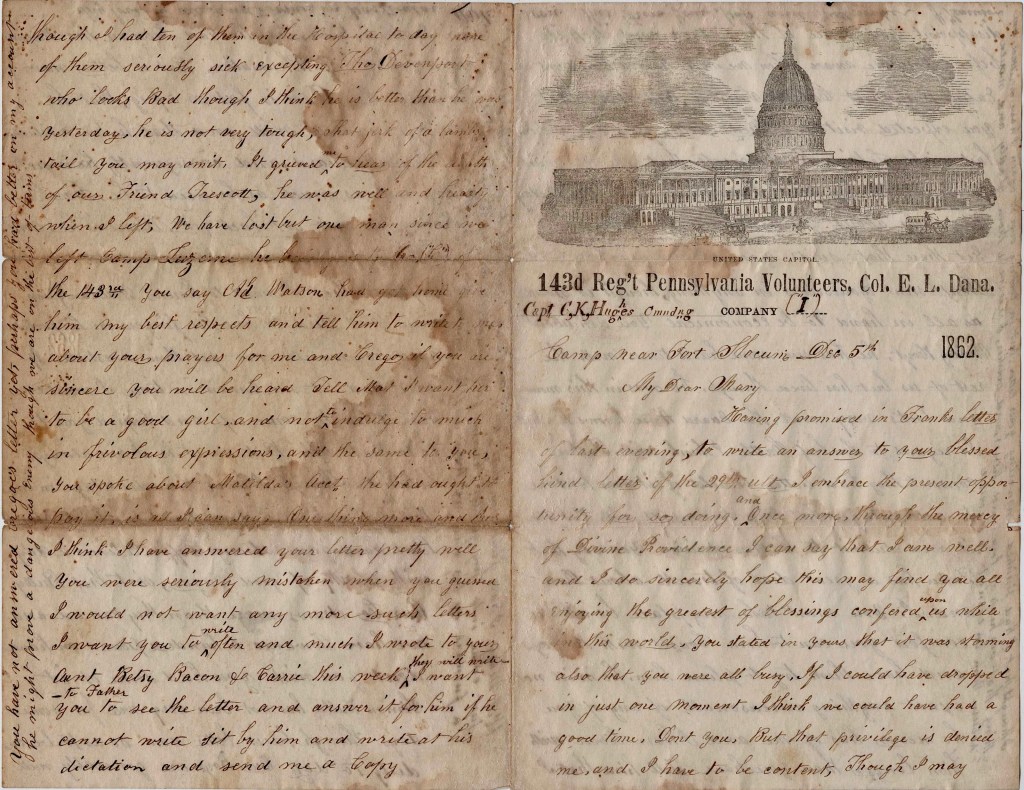

Simon Hubler has not been very well for some days though he is better now so as to be on duty today. Our Boys are generally well though I had ten of them in the hospital today, none of them seriously sick excepting Thomas Devenport who looks bad though I think he is better than he was yesterday. He is not very tough. The jerk of a lamb’s tail you may omit.

It grieved me to hear of the death of our friend Trescott. He was well and hearty when I left. We have lost but one man since we left Camp Luzerne, he belonging to Company C of the 143rd.

You say Ad. Watson has got home. Give him my best respects and tell him to write to me. About your prayers for me and [Warren H.] Crego, if you are sincere, you will be heard. Tell Mat I want her to be a good girl and not to indulge too much in frivolous expressions, and the same to you. You spoke about Matilda’s account. She had ought to pay it is all I can say. One thing more and [ ]. I think I have answered your letter pretty well. You were seriously mistaken when you guessed I would not want any more such letters. I want you to write often and much. I wrote to your Aunt Betsy Bacon and Carrie this week. They will write to father. I want you to see the letter and answer it for him. If he cannot write, sit by him and write at his dictation and send me a copy. You have not answered Crego’s letter yet. Perhaps you had better on my account. He might prove a dangerous enemy though we are on the best of terms.

Well Mary, I have filled my sheet and I hardly know how to quit. Thomas Devenport just came into my quarters have got smoked out of his own. He has a furnace in his and we have a stove which is much better.

My love to all and to some in particular. Write.

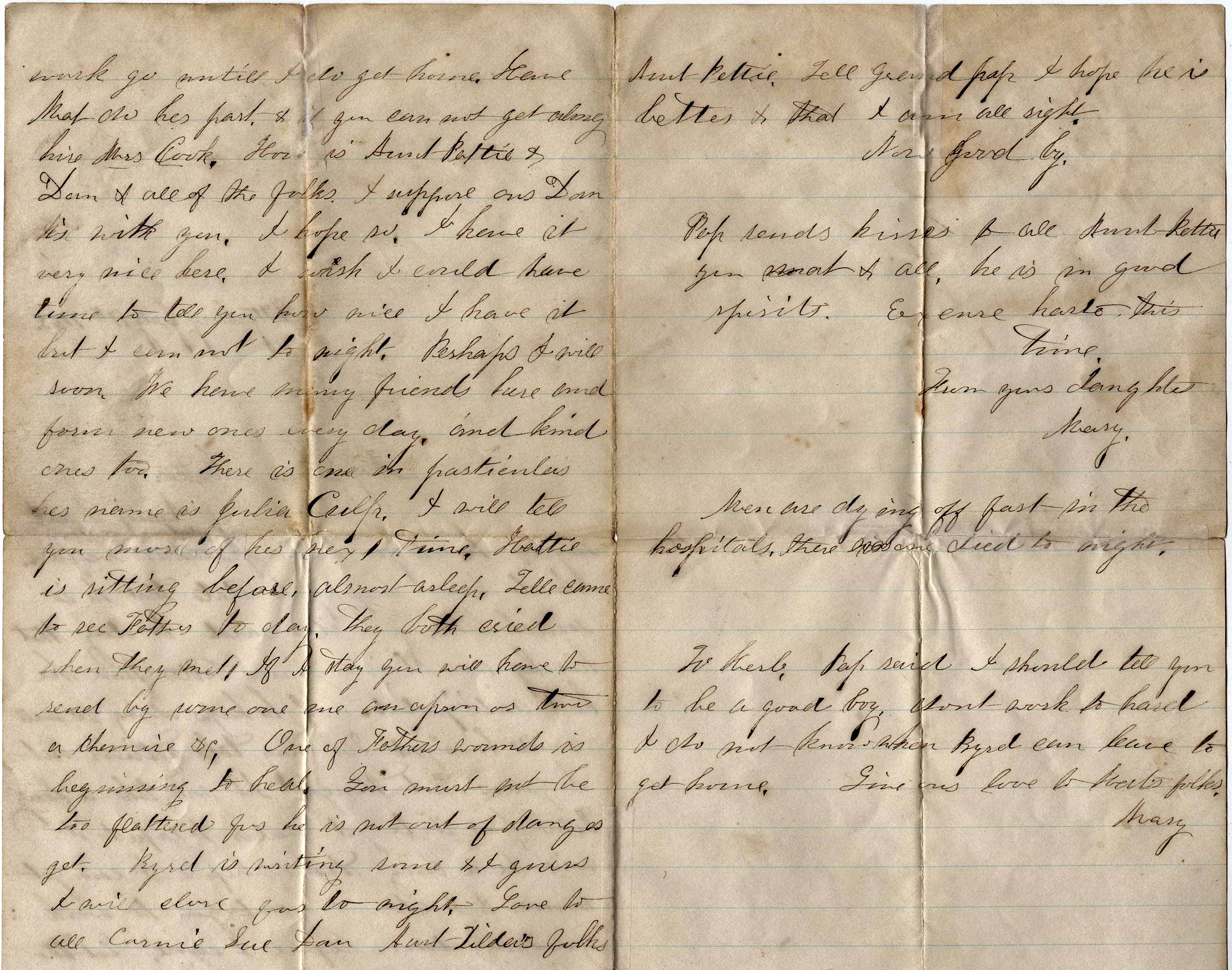

Letter 3

Camp near Fort Slocum

December 19th 1862

Much esteemed and dear gals,

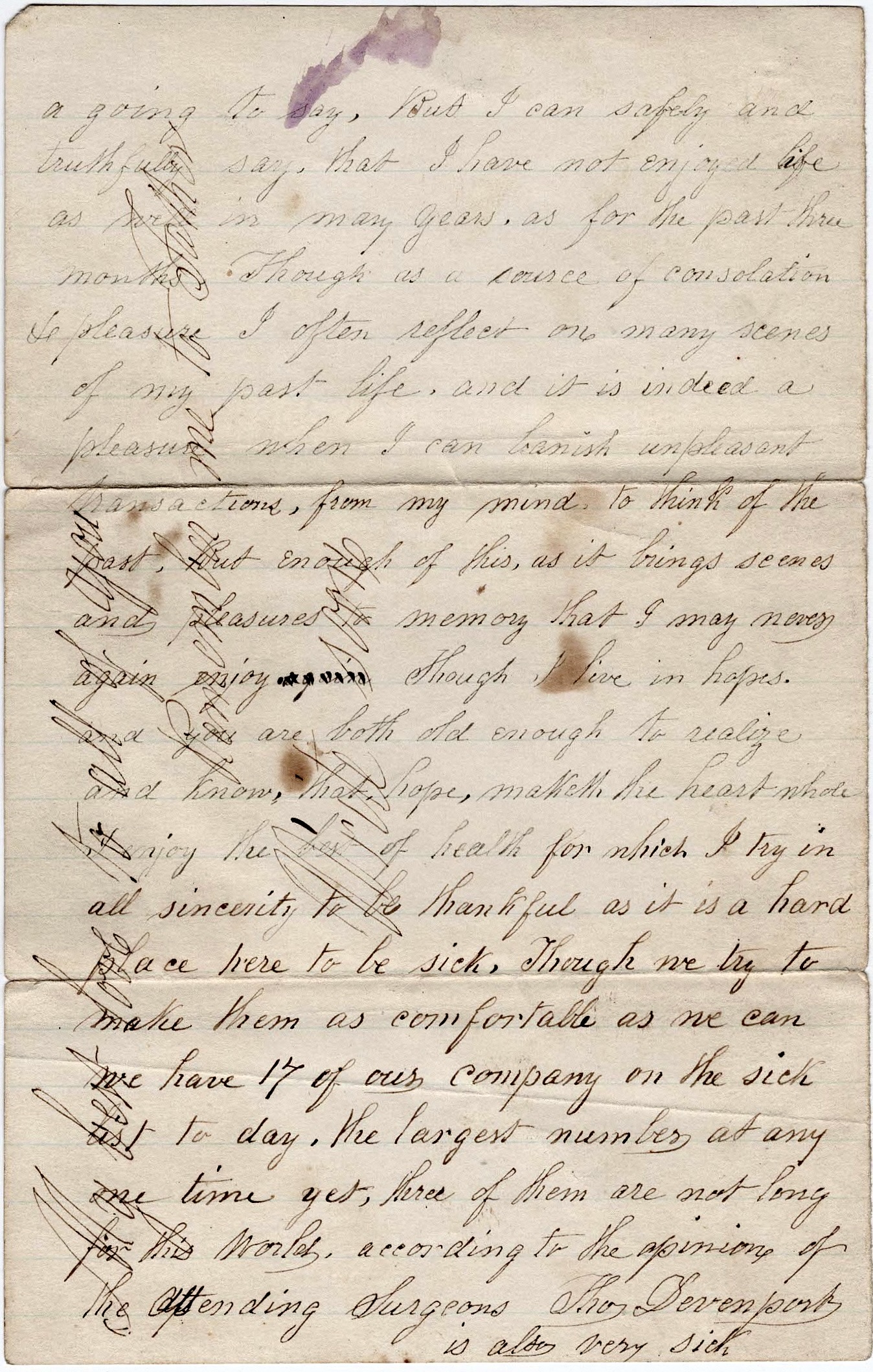

As I have a few moments leisure I have, after ruminating over many scenes and transactions of my past life, made up my mind that I cannot pass the time in a more profitable way to me than to converse with you, though I may not write anything that will interest you. Yet to think of th many pleasant hours we have passed together in singing and other past times is one of my chief amusements while thus separated from those whom I highly esteem and respect. You may think from my writing so often and the tone of my letters that I am down in the mouth or homesick or something else. But I can assure you that I never—-I was a going to say, but I can safely and truthfully say, that I have not enjoyed life as well in many years as for the past three months. Though as a source of consolation & pleasure I often reflect on many scenes of my past life and it is indeed a pleasure when I can banish unpleasant transactions from my mind to think of the past.

But enough of this, as it brings scenes and pleasures to memory that I may never again enjoy. Though I live in hopes. And you are both old enough to realize and know that hope maketh the heart whole. I enjoy the best of health for which I try in all sincerity to be thankful as it is a hard place here to be sick. Though we try to make them as comfortable as we can, we have 17 of our company on the sick list today—the largest number at any time yet. Three of them are not long for this world according to the opinion of the attending surgeons. Thomas Devenport is also very sick.

My best love to all of you. Remember me to father, Write soon.

Letter 4

Camp near Fort Slocum

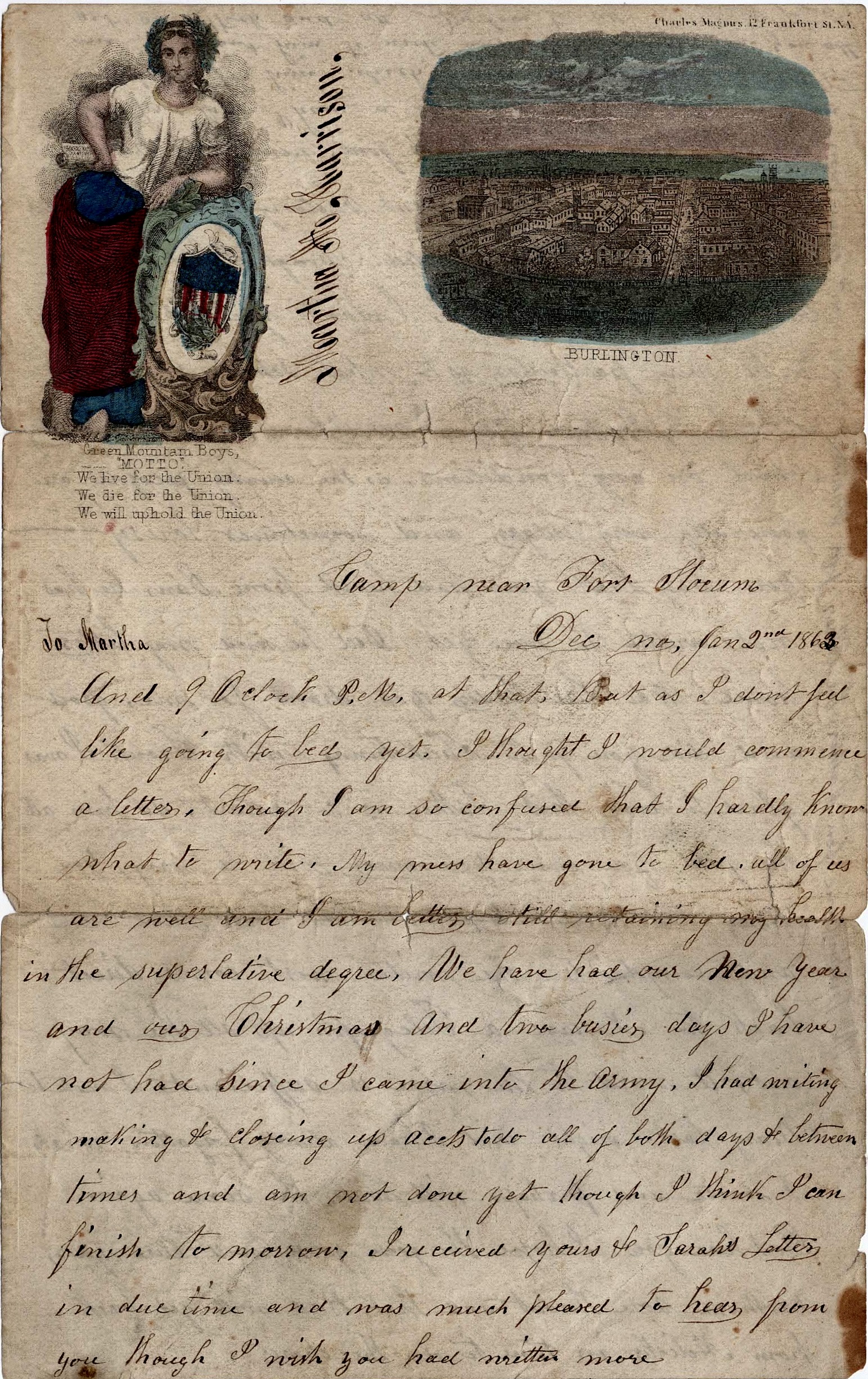

December—no, January 2, 1863

To Martha,

And 9 o’clock p.m. at that. But as I don’t feel like going to bed yet, I thought I would commence a letter though I am so confused that I hardly know what to write. My mess have gone to bed. All of us are well an I am better, still regaining my health in the superlative degree. We have had our New Year and our Christmas and two busier days I have not had since I came into the army.

I had writing, making and closing up accounts to do, all of both days and between times, and am not done yet though I think I can finish tomorrow. I received yours & Sarah’s letter in due time and was much pleased to hear from you though I wish you had written more. You can’t imagine how much good news from home does me. I hope those that went visiting enjoyed themselves ad I have no doubt they did. Though I had rather been at home with you, I want you and Sarah to be very particular as to what schools you teach. I think if I were you, I would not take a country school on any conditions as the country people are country people are generally very vulgar and sometimes lousy.

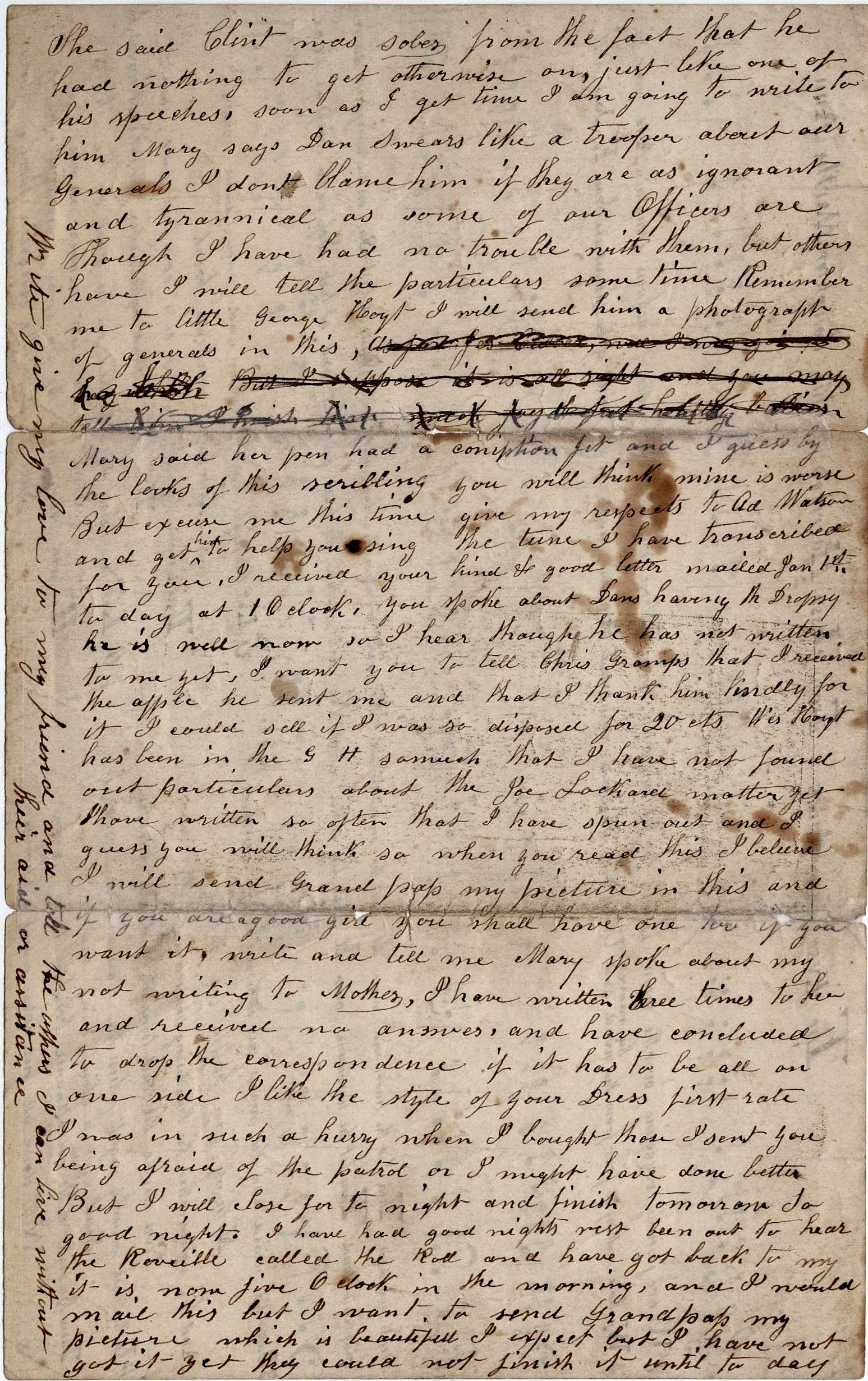

You say that you had heard from Dan. He has not written to me yet. Did he send my letter home? Was the cider you drank for me good? And did you go to Shickshinny with Frank? I was glad to hear that father is so smart. Do him all the good you can. You never will be sorry. You may tell your Aunt Matilda that what news and complaints she writes west comes direct back to [me]. I have a telegraph up all the way out. A word to the wise is sufficient. I wrote to Mary last night and I have already forgotten what I wrote and perhaps will write the same again. But here goes. I hope the goose grease will cure your mother’s sore throat and that Bird will get back from Melick’s in time to do the chores. She said Clint was sober from the fact that he had nothing to get otherwise on, just like one of his speeches. Soon as I get time, I am going to write to him. Mary says Dan swears like a trooper about our generals. I don’t blame him if they are as ignorant and tyrannical as some of our officers are, though I have had no trouble with them. But others have. I will tell the particulars some time.

Remember me to little George Hoyt. I will send him a photograph of generals in this.

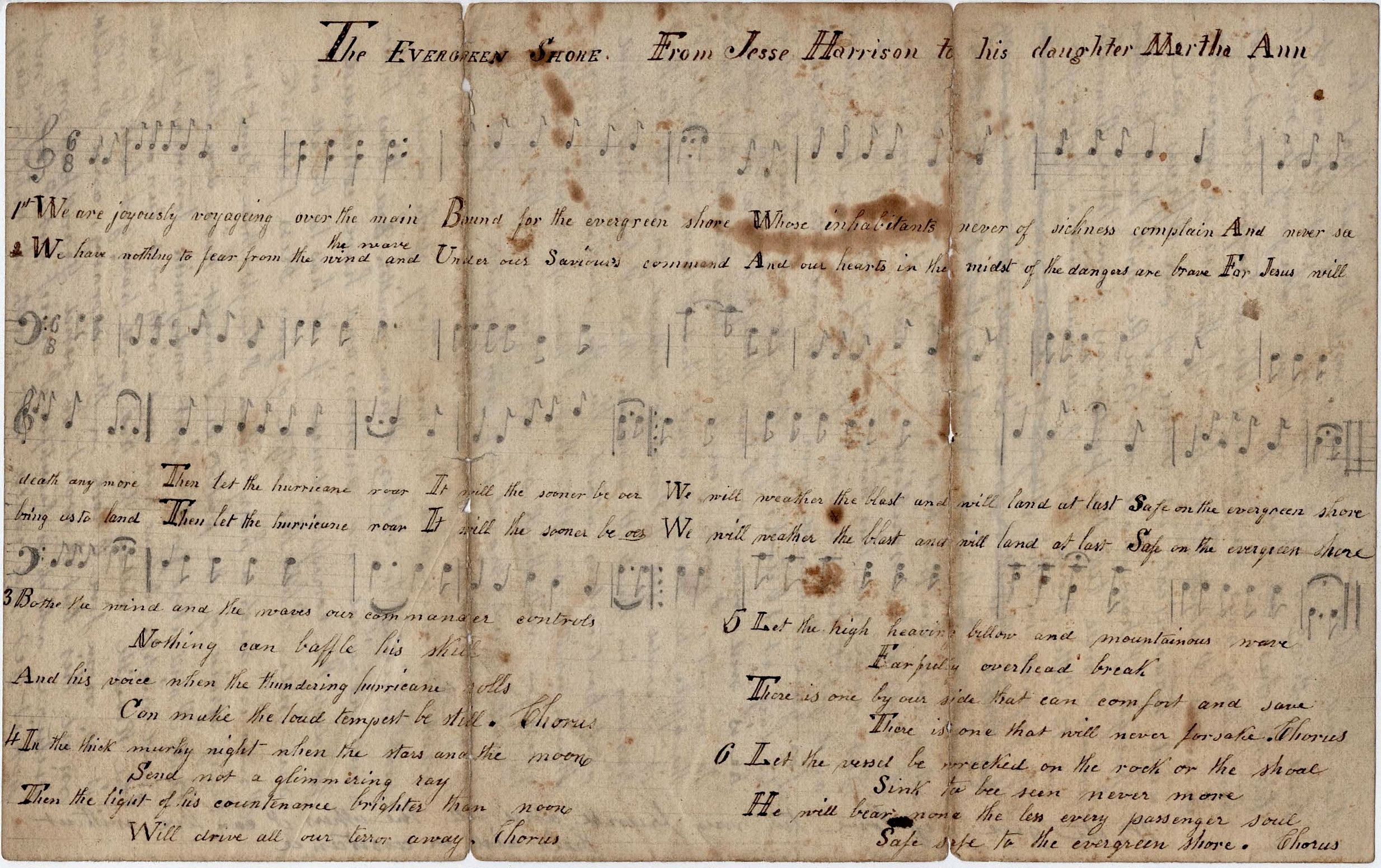

Mary said her pen had a coniption [?] jet and I guess by the looks of this scribbling you will think mine is worse. But excuse me this time. Give my respects to Ad Watson and get him to help you sing the tune I have transcribed for you.

I received your kind & good letter mailed January 1st today at 10 o’clock. You spoke about Dan’s having the dropsy. He is well now so I hear though he has not written to me yet. I want you to tell Chris Gramps that I received the apple he sent me and that I thank him kindly for it. I could sell if I was so disposed for 20 cents. Wes Hoyt has been in the Gen. Hospital so much that I have not found out particulars about the Joe Lockard matter yet. I have written so often that I have spun out and I guess you will think so when you read this. I believe I will send grand pap my picture in this and if you are a good girl, you shall have one too if you want it. Write and tell me. Mary spoke about my not writing to mother. I have written three times to her and received no answer and have concluded to drop the correspondence if it has to be all on one side.

I like the style of your dress first rate. I was in such a hurry when I bought those I sent you being afraid of the patrol or I might have done better. But I will close for tonight and finish tomorrow so good night.

I have had a good nights rest. Been out to hear the reveille, called the roll, and have got back to my [writing]. It is now five o’clock in the morning and I would mail this but I want to send Grand pap my picture which is beautiful I expect but I have not got it yet. They could not finish it until today. Tell Bird that I have a splendid sheet of paper and an envelope for him which I will send when he writes to me. I want him to write all the particulars how you all get [along], stock and all. My love to all. The pictures are for father. The other for Phebe. Yours will come soon.

Letter 5

Camp near Fort Slocum

Sunday Eve, January 11th 1862 [should be 1863]

To Mary and all from Jesse Harrison

My dear girl, I received your very kind letter this afternoon. It was not dated but it was mailed the 9th. It grieved me to hear that your mother is sick and would to God that I could drop in according to your wish. I feel that I would try to comfort her in her afflictions. You must fill my place. Do all you can for her. She has suffered much for you. And a mother. Oh, Mary, the value of ones’ own mother, we never appreciate. We never realize their worth until we are deprived of their kindness, of their faithfulness towards us, of their oft repeated kindly admonitions, and of the benefits we receive through the many sacrifice, both of health and comfort for us. And now my dear children each and all of you, I ask of you (and I feel that my request will be complied with), be kind to your mother; she hath ever labored faithfully for you, even to the sacrificing of her health which should not have been. But now you have the opportunity of returning those kindnesses and of repaying her for the many hours of toil and suffering for your sake.

And now, to Phebe I would say the image of your pensive face is continually before my eyes and I feel that for your sake I had ought to be with you and had I the wings of a dove, how soon would I use and soar above the pickets and guards with which we are now surrounded, though I would not desert. I would drop back in the morning, but this is only fancy. I know not what to say about my coming home now though I am going to make an effort. If Col. Dana and Capt. Hughes had the authority, I could start tonight. But they are like the boy that you know, neither can thy have anything to say. Even our commissioned officers can very seldom get a pass to go to Washington. Yet I will try to get a furlough for a few days though I have but faint hopes that I shall succeed. But if I do, you will see me early.

And now to close. Cast your burden on Him who is able to sustain you. With patience and resignation, abide the will of heaven, and may the Father of Mercies support you and pour into your bosom the rich consolations of His grace and preserve and strengthen you for your family. May God bless you and breathe into your bosom peace and cheerful resignation is the prayer of your absent one.

I received a letter from Daniel day before yesterday and one from Wm. R. Monroe yesterday and have answered both of them. They said they were both well and enjoying themselves first rate, though they were not anxious to see any more fighting. They are about 2 and a half miles apart. Will said in his letter that on Christmas day, he was over to see Dan and had a good visit. He also said that he had just received a letter from Frank enclosing a dollar bill and that the talk was that the Division in which he is are about to remove to Pennsylvania to recruit and he hoped to God they would.

Did Martha tell you that [Warren H.] Crego was dead? If I wrote anything of the kind, I must have been asleep when I wrote. He is not dead but has been on the sick list for several days. Tell Aunt Patty to do as she agreed to before I left, and if I don’t live to reward her, my prayers are that heaven’s choicest blessings may rest upon her and that she will be rewarded by Him who is a Father to the Fatherless and the Widow’s God. Tell Matilda that I feel grateful for her kindness. Tell Lib Hubler that I consider her extremely lucky. Simon Hubler is getting along fine though he came very near committing a grave error by deserting with Pealer &c, But as luck for him would have it, I had him detailed as Corporal of the Fatigue Party on the day they left. He himself told me the arrangement. I wish Lib would write to him and advise him.

I received Frank’s letter and answered it. Did he receive my answer? Albert says he has answered yours. I have sent each of you my photograph and one to Father. Have you received them? Write to me soon. Write to me often. I will come home if I can but don’t be disappointed if you don’t see me. Did Sarah K M get her ring? I sent it in a letter by Joseph Moss. Write and tell me everything. Remember me to ll enquiring friends, To Dr. Warner and family in particular & to Jarius Hoyt. I would like first rate to see you all just a minute anyhow. I am perfectly well and like the service better every day. Give my best love to grandpap and reserve each of a good share. But I must close. Excuse this scribbling as I wished to send by this evening’s mail which is called for at half past eight. Good night. Good night.

Letter 6

Camp near Fort Slocum

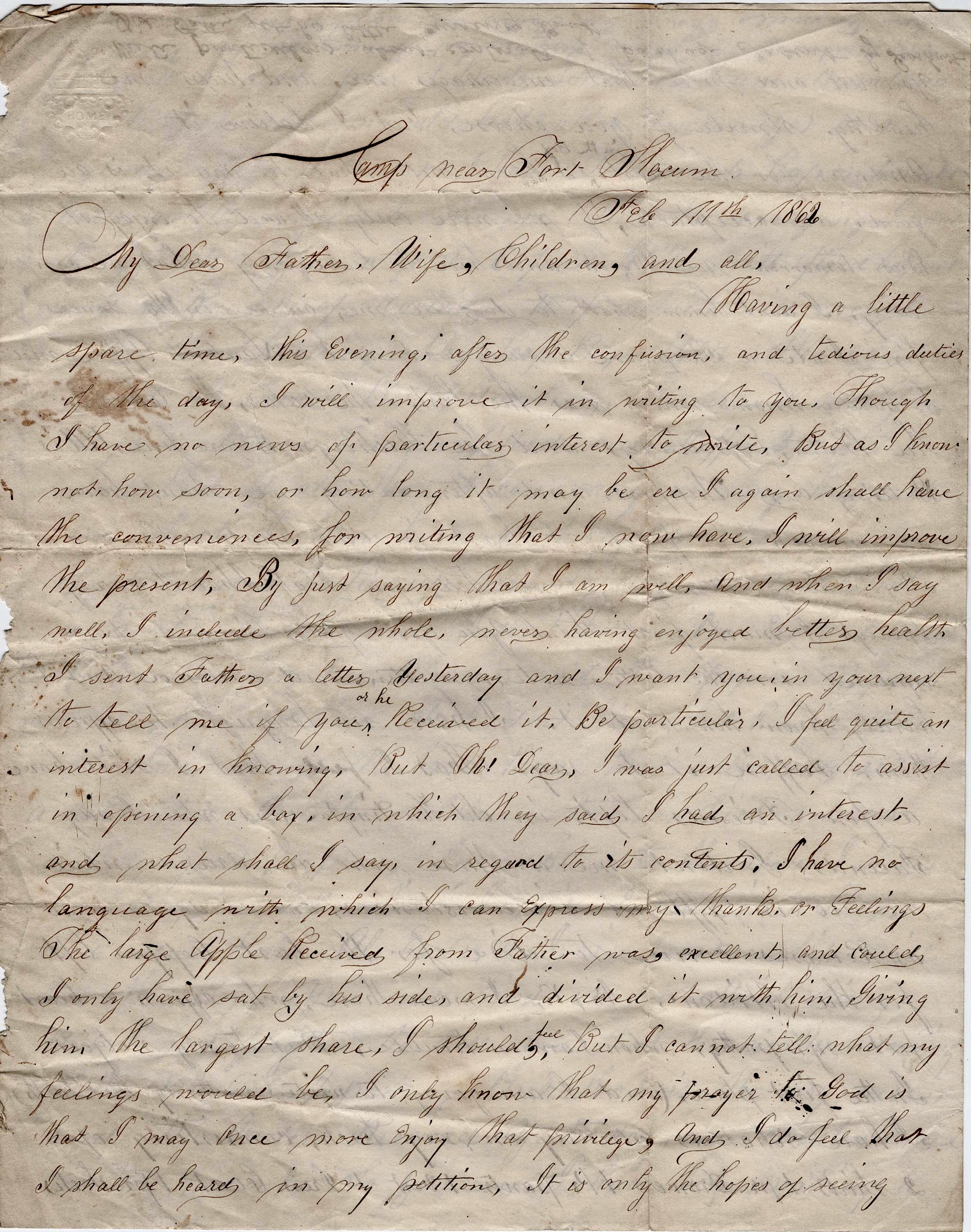

February 11th 1862 [should be 1863]

My dear father, wife, children, and all,

Having a little spare time this evening after the confusion and tedious duties of the day, I will improve it in writing to you though I have no news of particular interest to write. But as I know not how soon or how long it may be ere I again shall have the conveniences for writing that I now have, I will improve the present by just saying that I am well. And when I say well, I include the whole, never having enjoyed better health.

I sent father a letter yesterday and I want you in your next to tell me if you or he received it. Be particular. I feel quite an interest in knowing. But oh! dear, I was just called to assist in opening a box in which they said I had an interest and what shall I say in regard to its contents. I have no language with which I can express my thanks or feelings. The large apple received from father was excellent and could I only have sat by his side and divided it with him, giving him the largest share, I should feel—but I cannot tell what my feelings would be. I only know that my prayer to God is that I may once more enjoy that privilege. And I do feel that I shall be heard in my petition. It is only the hopes of seeing you all once more that encourages me and keeps me healthy. Smile if you choose, but I believe it.

And, as for the rest in the box, I know not what to say. It is all good, all acceptable. If we were only allowed to enjoy it. But tomorrow we march and have to leave only what we can carry. I don’t know what to do, tell me, all are in the same fix. I ate a sheep nose, a rusty coat, and a Laubach apple and I hardly know which was the best. The cakes, the chicken, the butter, especially, and the hickory nuts are fine. All is getting our suppers and after eating we shant have so much to pack, at least in our knapsacks, and as I go along, I might as well tell you what I have to carry. Though I must first thank you for your kind wishes expressed in the little notes written and enclosed. And I hardly know how to do it. I have no language to express them. Suffice it to say that I feel that I still have a few friends left in old Huntington and ready as soon as reverses come to dive for the last copper left for the Widow. No, no, I mean those who express a heart felt sympathy when I am in trouble.

But to my object. In the first place (and I am going to write nothing but truth), I have what is already on my back, consisting of 2 shirts, 1 pair drawers, 1 pair pants, 1 vest, 1 dress coat, 1 pair socks, and a noble pair of boots, for which I a also indebted to you. Also my old hat which I wear yet as a general thing, though I have Lieutenant’s cap on tonight. You would smile to see me.

But the carrying I want to get at. I have a good Enfield rifle with fixed bayonet and 60 rounds of cartridge, 16 of which will weigh a pound, then cartridge box, cap box, belt, shoulder belt, sword and sword belt, revolver, haversack with five days rations, canteen filled with coffee 3 pints, and last of all that I can carry is my knapsack in which I now have 6 shirts, two pair drawers, a lot of bandages to up wounds if I happen to have courage enough to get close enough to to the enemy to receive them, one woolen blanket—a mate to the one I sent home, one excellent oiled rubber blanket, one blouse, and then paper, ink, pens, plate, knife and fork, and I don’t know but I will take a stove along—we have them that only weights 2 lbs., a patented portable soldiers stove, which answers a very good purpose. In addition to the above, I have my carpet sack which I will enclose in a box and send home. Al[bert] Earls & I in partnership will fill the box. You will find it at Shickshinny.

But I had for gotten to tell you that this is the morning of the 12th of February, half past 4. But that is the very case and the orders received yesterday are countermanded for the present so you see I have been making a lot about nothing. Still our orders are to keep our moveables packed and now I must come to a close as my left eye is still too weak to write much by candle light. Still I hate to pay postage and not have the sheet full so I will scratch a little more.

I attended meeting last Sabbath at the Soldier’s home about one mile from here and a more interesting service I never witnessed though it was rather lengthy, lasting three hours. The denomination is styled the Protestant Episcopal Church [see St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Rock Creek Parish]. The building was erected in the year 1719 and is still a splendid structure though it was repaired in 1790. The interior is decked with evergreens throughout, crosses, wreaths, and emblems of all descriptions cover the walls. They have an organ from which many beautiful strains of music was drawn and when accompanied by the soldier like voices of our old Colonel [Dana] and Lieutenants [C. C.] Plotz, [Charles W.] Betzenberger, and my humble self, the effect was highly imposing. The oldest marble in the yard to the memory of the departed was dated 1775 [see Robert Cramphin, died April 1775]. The building is situated in a beautiful park, interspersed with evergreens. The Mountain Ash through which the gravel walks wind most beautifully. There are several family vaults in which the coffins of the dead are visible and had I time I would give you an outline of services but I have not as the reveille is beating and I must attend. Hoping this may find you all in health and good spirits, I subscribe myself yours in love & affection, — Jesse Harrison

To all of you.

Ellis [B.] Gearhart & Z[ebulon] S. Rhone deserted last Monday. We had treated them too well though their father are more to blame than them.

Letter 7

Camp Dana

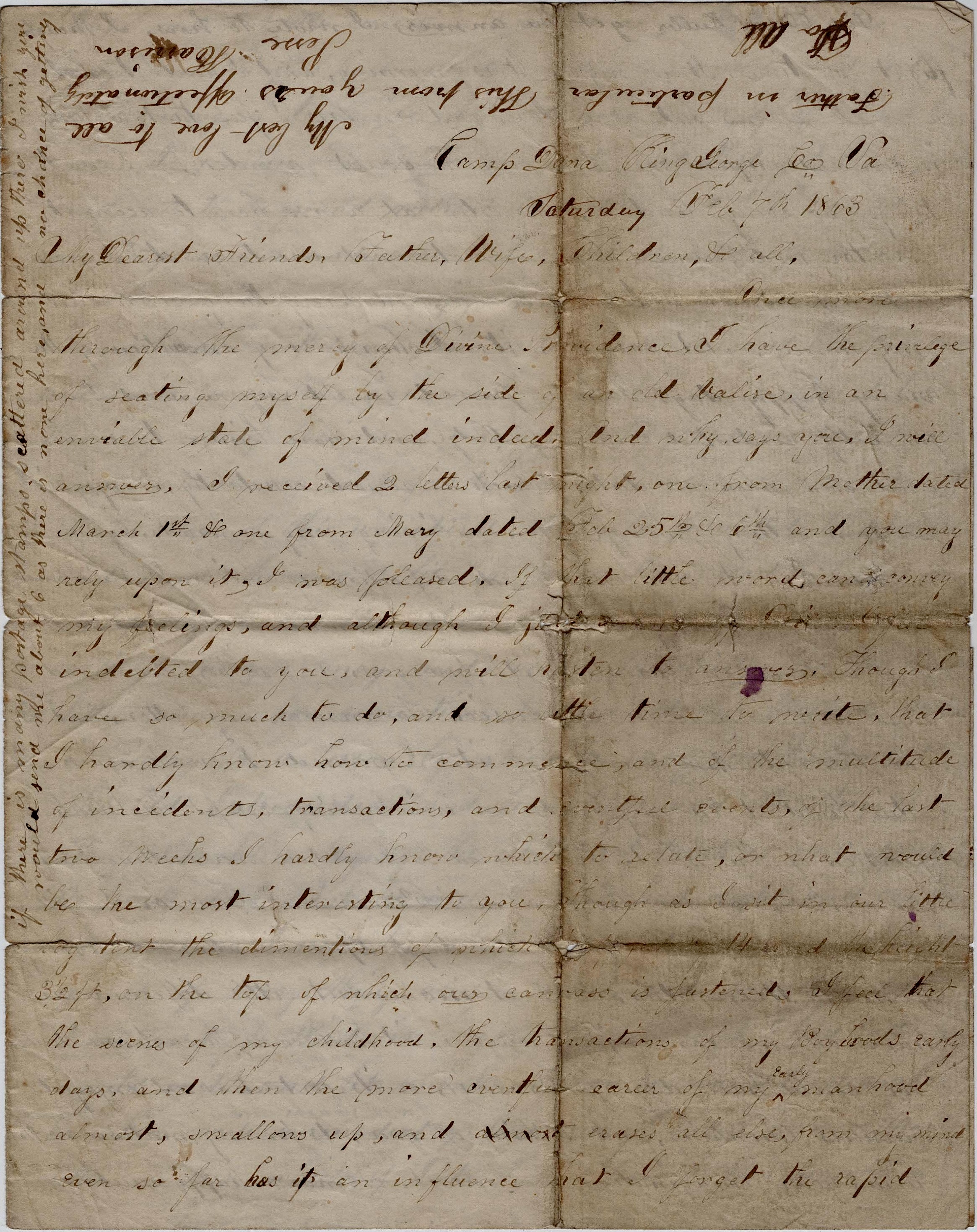

King George county, Va.

Saturday, February 7th 1863

My dearest friends, father, wife, children and all,

Once more through the mercy of Divine Providence I have the privilege of seating myself by the side of an old valise in an enviable state of mind indeed. Any why, says you. I will answer. I received two letters last night, one from mother dated March 1st, and one from Mary dated February [January] 25th & 26th, and you may rely upon it, I was pleased. If that little word can convey my feelings, and although I just [illegible] indebted to you and will hasten to answer though I have so much to do and so little time to write that I hardly know how to commence. And of the multitude of incidents, transactions, and eventful events of the last two weeks, I hardly know which to relate, or what would be the most interesting to you though as I sit in our little log tent, the dimensions of which are 12 [?] feet by 14 feet and the height 3 and a half feet, on the top of which our canvas is fastened, I feel that the scenes of my childhood, the transactions of my boyhood’s early days, and then the more eventful career of my early manhood almost swallows up and erases all else, from my mind, even so far has it an influence that I forget the rapid flight of time.

It is night, it is morning, and I heed it not. A week seems but as a day, and in this I feel that a blessing is conferred upon me. You will no doubt wonder how I can take things so coolly. And I am often at a loss how to account for the indifference (I know not what else to call it.) I feel not but what I dearly love all, and everything connected with my home. No! far from it. I cherish ever association of the many happy days I have passed in Old Luzerne, and I am perfectly contented when off duty, and have leisure to ruminate and even when on duty, which is almost constantly, I enjoy it seldom getting weary, often relieving my comrades by carrying in addition to my own load, a portion of theirs.

But I commenced this letter intending to answer yours which I shall fail in doing if I continue in this strain. So here goes. To mother, I was glad that you came to the conclusion to answer my letter and as for the interesting portion of it, I perused it over & again and still hold it in my hands. All is interesting except the blank portion of the sheet. I was glad to hear you were getting along so well. As for the box you and Frank sent, Dan or I will never see, the regiment which Capt. Spoce is attached having gone to Alexandria. But it makes but little difference. We have all we can enjoy though if it had come through, no doubt we could have done justice to it, or its contents, and enjoyed ourselves thinking and talking of you. As for my meeting with him, your imagination was correct. It was a happy meeting.

Though one thing I have already written concerning and that is the borrowing of trouble in your despair of ever seeing either of us again. Remember, there is one who hath said that not even a sparrow shall fall to the ground without His notice, and I have confidence in His promises, and also that He will do all things well, and in His confidence, I can enjoy all things both sweet and bitter, and since I have withdrawn from certain influences, and have abandoned bad habits, everything goes well, and it does really seem at times that my cup of blessings is running over. My prayers also coincide with yours. That we may ever be found faithful in the performance of our duty and at the close of this unnatural strife be permitted to return and enjoy the close of life in peace.

I was glad to hear of the prosperity of the livestock and as for the prices of such articles as you may need, in all probability there will be but little change for some time to come. As for Herbert’s watch, it may be a lesson by which he may profit. You get the Old Introduction and have him read the story of Benjamin Franklin buying the whistle. I think it is quite appropriate.

As for Bird, I think he and Herbert had ought and can do as much as I used to, which if they do, you can all have as much of everything as you want and something left. I will write to Bird in regard to it, though I had rather he would write and let me know how he wants to manage. Have him write immediately. And now, I must answer Mary’s letter in this which if I do, I will have to commence soon.

And to commence. There os no use of my telling you I was pleased to hear from you once more. How was it that you neglected writing so long? You ask me if I have seen Wood yet. I have not though I intend to soon if I get time. I wish you would write to him, that you would tell him of my location, and perhaps he has more time to visit than I have and would come and see us.

As for your parties, you already know my opinion in regard to them. Though I do not wish you to let them interfere with your duties or studies—-but I am called [away]

Sunday afternoon. You will see that I am a good while writing this letter. The reason for which is I was kept in duty yesterday and last night until half past nine, and this morning after roll call, morning reports, and inspection, I went over to see Dan. I met him coming over to see me and as I had not been over to his camp, he turned round and we went over to the camp of the 7th Indiana & 56th [Pennsylvania], who are together. Though Dan’s tent is nearly a half mile farther in to which we went, to give you a description of it would require language of which I am not master. Though as a sample, or to give you a little insight, just imagine a hole dug in the ground about 6 feet long, 5 feet wide, and three feet deep, over which is spread two shelter tents stretch on a pole sustained by two crutches. In addition to this, he has three other pieces of canvas, two stretched so as to lap on the others, the other for the gable end under this last. The earth has not been disturbed and it serves for a table, a shelf, a seat, a closet and many other purposes. Then from the first apartment you will see a hole dug straight out from the bottom near three feet which then turns up and opens on the outside, thus forming both fireplace & chimney and makes it comfortable. He has a good berth.

I stayed about two hours, ate some bread and butter, crackers, onions, and drank some whiskey, and then he came over with me and is here now. Though by the way he ready my letters and I read his, he has all he needs—that is, to live on, though he had to pay 50 cents per pound for the butter. But as I must soon close this letter, I would just say that we are both of us well and enjoying ourselves well.

Yesterday there was heavy firing on our picket lines some three miles distant. All was excitement in our camp. Troops of cavalry were passing us all the time. Soon orders came for us to empty out all our cartridges which being done, each man was furnished with 60 rounds of new ones. The firing lasted about two hours. I have not heard the particulars. One thing I know, I had no fear. I still retained my indifference though I know not what my feelings may be when brought before the enemy face to face. But I expect soon to know. Dan says I will be as cool as a cucumber.

I want you to excuse this miserable sheet. You must not expect any more fancy writing from me. I have none of the conveniences or materials.

Letter 8

[Editor’s Note: On the 20th of April, the 143rd Pennsylvania accompanied the division on an expedition to Port Royal, below Fredericksburg, where a feint was made of crossing the river. They did not cross and returned to their camp on the 22d.]

Camp Dana

April 23, 1863

My dear friends, father, wife, children and all,

According to a promise made in the two last little notes I wrote to you since my return, I seat myself for the purpose of giving you a little history of my journey from home to this place. As you are all aware, with a sad heart on the morning of the 16th inst., I left the hallowed associations of my early days on an expedition fraught with interest, and the result of which is unknown. I said with a sad heart I left. And you may infer from the expression that I regret the steps I have taken, but I can assure you that knowing what I have already learned, and after the hard experience of the past few months, were I free, I would again enlist. Yes, my friends, I feel that I am in the line of duty from which I would not swerve and my regrets are only the being deprived of the society of my family and friends and of trying to be a comfort to the few remaining days or years, I hope, of one to whom I owe all I have, or am.

But to my sojourn, I left Shickshinny 15 minutes to ten and after a pleasant ride, arrived at Northumberland 15 minutes to 1 p.m. We lay there about one hour and then went over to Sunbury which lay in sight, halted, and soon learned that we would have to remain there until 11 o’clock at night. And what do you suppose were my feelings at that time. One whole day, as it were, lost in my existence. I might have stayed at home and been just as far on our journey on the day following. But I was there and had ample time for reflection. My thoughts were not controllable and tears would flow, though I comforted myself with the maxim or saying, that the brave are tenderhearted, and I suffered them to flow. I only got out of the car for a few moments once, and then to get shaved. Could I find language to tell you what my feelings were for those longest ten hours I ever passed, I would, but language fails me and I must forbear.

At half past 11 we started and arrived at Harrisburg at 3 o’clock morning 17th. Halted a few moments and then on to York where we arrived at the break of day. Thus passing along, we arrived at Baltimore half past 10 a.m. and to Washington at noon. Took dinner, went to the Provost Marshal, got our passes for the Army of the Potomac, which it was said was on the move, but we were there and could not go until the next day. We went to the Carer Barracks Hospital near Fort Slocum and seen our Boys that had been left sick. We found them looking well and anxious to go with us but could not until a regular transfer could be made. Benjamin Belles & Edward Traxler were the only ones you would know. At night we went to the theatre, though I had rather went to bed. Still the Boys insisting so hard, I went. The plays were very good but at times my thoughts would be so engrossed with home, that when asked is not that splendid. I would have to ask what. I will enclose a programme that you may see the names & of the actors.

At 11 we returned to our lodgings, slept until morning, eat breakfast, and at 7.30 o’clock set sail. Touched at Alexandria at half past eight, at Aqua Creek 11 a.m., saw Capt, Tubbs who with many others had been sent to the General Hospital, arrived at Belle Plain Landing at 3 p.m. where if appearances indicate anything, they were as glad to see us as we were to see them. Daniel came over in the evening. Was right well. My trunk I had to leave at the Landing and he said he would come over the next day since which time I have not seen him though he sent word that he would have to march the next day.

And now I must say something about the marching, &c. &c. When I arrived in camp, I found all things packed. Each one having 8 days rations with 60 rounds cartridge. I called on the Colonel and other Field Officers and I never experienced a more cordial or warmer reception than on that occasion. They were all pleased, both officers and men. After reporting myself, I drew my rations and prepared for marching as the orders were to hold ourselves in readiness to form at a moment’s notice. Many regiments had already gone. Deserted camps were on every hand, and the appearance was gloomy indeed. But night came on apace and I had a good night’s rest.

Sunday morning was beautifully warm and pleasant though much here was to do. I had but little time to think of home and no doubt it was all the better for me. But the day passed along. Drill, reveille, inspection, dress parade, all passed along in a satisfactory manner. Night came and we all retired with the expectation of being called, perhaps within an hour. But we were not disturbed and at daybreak the reveille awoke us and we found the rain pouring down in torrents. Still the orders came to us to be in line of battle in half an hour, and at 2 o’clock the regiment started, marched out of camp, and formed Division, composed of 5 regiments, viz—143rd, 149th, 150th, 135th, 151st, marched to our picket lines about three miles and halted a half hour. It being near five o’clock, we started and did not halt again until half past ten at night when we had orders to rest one hour, at the expiration of which we again fell in and marched until half past 3 in the morning. Built fires out of secesh fence and then laid down in the mud until the break of day when we were again ordered to march. We traveled east of south and at 12 noon arrived in sight of Port Royal [below Fredericksburg], having traveled 26 miles of the worst roads I ever saw, the most of the way in the night, raining hard from time to time. We started [halted] until near daylight in the morning. But more of this anon.

The Division formed by regiments sharp shooters were selected from different companies, the command of which was given to Capt. [Chester] Hughes [of Co. I]. I was also placed on the right of the same. The Colonel came to us after we had taken our positions and gave us our instructions which was to protect the pontoon bridge builders from the enemy’s fire by popping off all who should appear or molest us. We were then near three miles distant their flags and signal flags waving gracefully or I should say disgracefully in the hill back of the town. After these dispositions were made, our Colonel rode up to us and says, “Boys, you have an honorable position and a dangerous one though I have all confidence in your courage and have no doubt you will perform your duty. We then started about one mile towards town, halted, built fires of secesh fence, cutting off posts and burning rails, thus destroying miles of fence which enclosed the most beautiful plantation I ever saw. But more of this anon.

The Boys were then ordered to rest and those that wished it to make coffee and it would have done you good to have seen us flying around. We had a good cup of coffee while the Officers reconnoitered. They soon returned. Orders were given to get in ranks and load our rifles which was soon done. We then marched toward the town until we arrived within 30 rods [165 yards] of the bank of the river when we were halted. Skirmishers were thrown out on either side, regiments filed out by divisions and placed in order of battle. Gen. Doubleday then gave notice to the inhabitants that they might have two hours to remove the women and children and you would have smiled to have seen them skedaddle over the hill back of the town. Our little army was all on tiptoe expecting a shell or ball to commence the picnic but none came. We then waved the red flag of defiance which was not answered. Our generals then surveyed the defenses of the town and with the help of glasses soon found that appearances were deceitful. Instead of a town nearly deserted except by women and children, they found that the houses and the rifle pits, besides a battery, were filled with men ready to pour a deadly fire upon us as soon as we undertook to cross the river.

A council of war was held, the decision of which was to keep up appearances until after dark and then to fall back, though we knew it not at the tie. Skirmishers were then thrown out to build fires on each side and in our read and soon a line of fires some [rest of letter is missing]

Letter 9

Camp near Falmouth or Fredericksburg

In the woods near the Rappahannock

May 12, 1863

My dear son,

I seat myself this beautiful morning to answer your very kind and welcome letter which I received in due time, and you may rest assured I was pleased. I had waited long and anxiously for a line from you and at last it came. But you never will know the pleasure until you are situated just as I am which I pray God may never be. But to answer yours, you spoke of planting potatoes. Be careful and select the best seed as some we have been planting hardly pays. You are full early for corn. But perhaps not too early. I was glad to hear that you got along with your work so well. Don’t work too hard—only be steady and you can so all that is necessary.

You spoke of laying up some stone fence. There is nearly stone enough between Fritz and us for a wall and he told me if I got the stone he would get it laid up. Try him. Hat said the same of the little strip by the same field. If they do anything, you must have the line established between Fritz, Uncle Mat, Williams & us. If you think best you may get some good hand to lay up the strip you spoke of between us and J. E. and along the lane up by the woods as that fence will have to be repaired otherwise.

Telle got with us last Saturday and looks well. He is on picket. I wish you had thought a little sooner about the tobacco though what Herbert sent came first rate, I tell you. About the calf, you know my opinion. I disapprove of raising it as it will fetch more at five weeks of age than one year.

As for your coming down, I should like very much to see you but even if you started, you could not get here now as our sutlers, one of whom is here and the other in Washington, cannot get back and firth. Daniel is here or close by and was here last night. He is right well. I bought him a good ham yesterday for 10.5 cents per lb. he could not get off their commissary. I was glad to hear Ezekiel was better. Give my love to him. I was glad to hear that things look well. You must get the cattle in pasture over by the Mill Brook as early as you can before the wild grass gets tough, If Frank wants to sow the field you spoke of, have him do so. What have you done with the red oxen? I would liked very much to have been at J. Hoyts party but could not come.

Daniel got a letter from William R. Monroe yesterday. I read it. He is well and says he is enjoying himself first rate. As for myself, I feel first rate again though I never was so near used up in my life as I was the few days past, the particulars of which I have already written. Many times I thought of you and would ask the question, what would become of Bird if he was here. Our generals will say that our Brigade has done the hardest marching that has been done since the retreat of the French from Moscow.

The weather is very warm here now, seemingly as much so as our harvest weather. Our camp is situated on a rise of ground on which the Oak [illegible] has been suffered to grow. The leaves of the trees are nearly half size and I seen timothy and clover over a foot high one week ago. This is a beautiful country—no stone, soil rich & loose, though I would rather live in Old Luzerne. Simon Hubler just came and wanted a pass to go and get some tobacco. I gave him one. 39 of our men are out on picket. Capt. Hughes is laying on our bunk. He is not well. Has a touch of the fever and expects to be sent to the general hospital and then what will become of me, I know not. But as you say, my sheet is full and I must close. My best love to you all. Remember me to Grand Pap and read this to him.

Jesse Harrison to Bird & all.

Write soon and write everything.

Letter 10

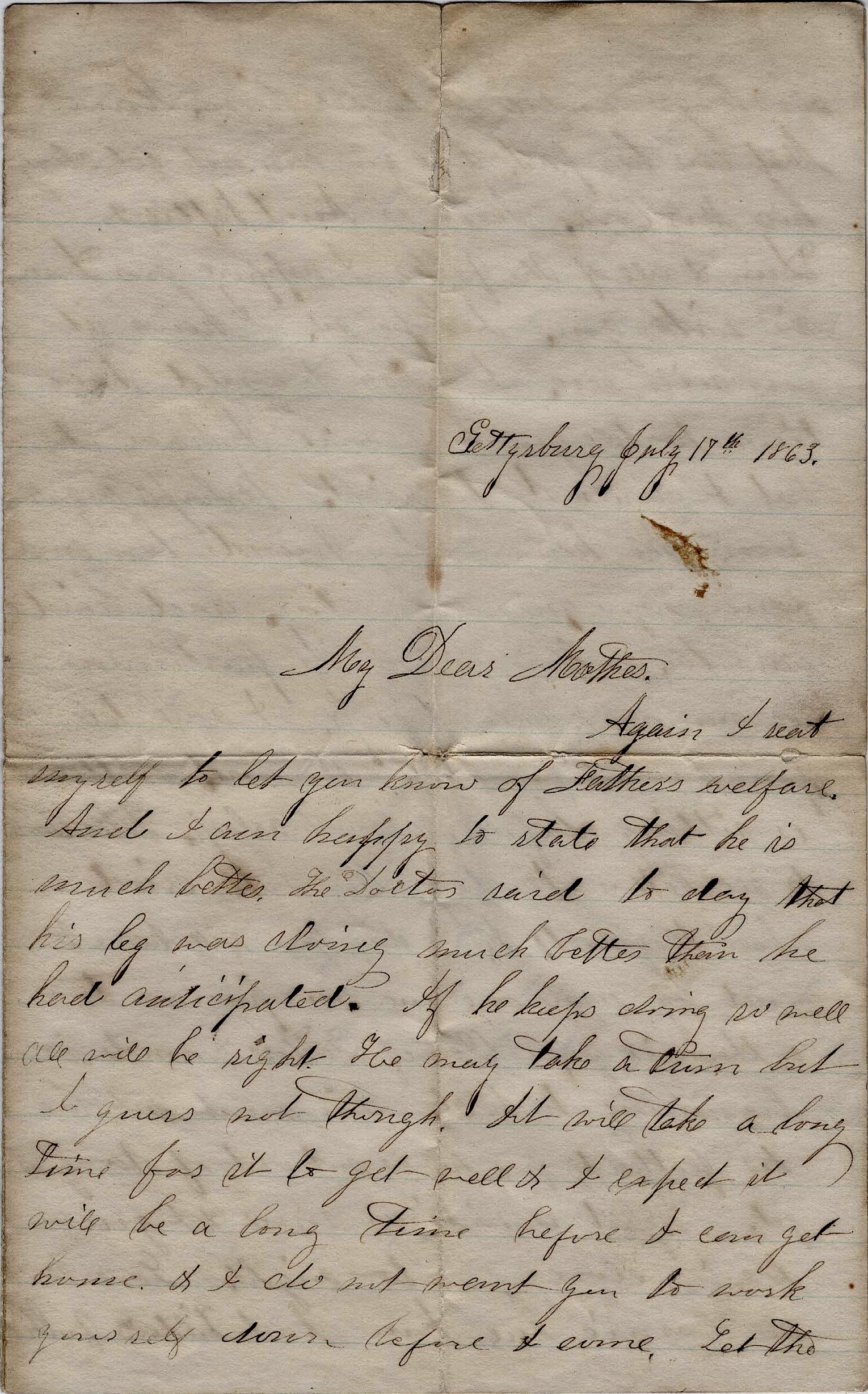

[Note: This letter was written from Camp Letterman near Gettysburg where Jesse Harrison was being treated for his leg wound sustained in the fighting on Day 1 at Gettysburg. His oldest daughter, Mary, wrote the letter to her mother, updating her on her father’s status.]

Gettysburg [Pennsylvania]

July 17, 1863

My dear mother,

Again I seat myself to let you know of father’s welfare. And I am happy to state that he is much better. The Doctor said today that his leg was closing much better than he had anticipated. If he keeps doing so well, all will be right. He may take a turn but I guess not though it will take a long time for it to get well and I expect it will be a long time before I can get home & I do not want you to work yourself down before I come. Let the work go until I do get home. Have Mat do her part & if you cannot get along, hire Mrs. Cook. How is Aunt Pattie & Dan and all of the folks? I suppose our Dan is with you. I hope so.

I have it very nice here and wish I could have time to tell you how nice I have it but I cannot tonight. Perhaps I will soon. We have many friends here and form new ones every day—and kind ones too. There is one in particular, her name is Julia Culp. 1 I will tell you more of her next time.

Hattie is sitting before, almost asleep. Telle came to see Father today. They both cried when they met. If I stay, you will have to send by someone me an apron or two, a chemise, &c. One of father’s wounds is beginning to heal. You must not be too flattered for he is not out of danger yet. Byrd is writing some and I guess I will close for tonight. Love to all—Carrie Sue, Dan, Aunt Tilder’s folks, Aunt Pettie. Tell Grand Pap I hope he is better & that I am all right. Now goodbye.

Pap sends kisses to all, Aunt Pettie, you ,Mat, and all. He is in good spirits. Excuse haste this time. From your daughter, — Mary

Men are dying off fast in the hospital. There was one died tonight.

To Herb, Pap said I should tell you to be a good boy. Don’t work too hard. I do not know when Byrd can leave to get home. Give our love to Mat’s folks. — Mary

1 Julia Culp has been forever immortalized in Gettysburg’s history as the sister of John Wesley Culp who hailed from Gettysburg but fought for the Confederacy. 16 year-old Julia was the youngest of the Esaias Jesse Culp family. Her brother, John Wesley Culp, was killed on Culp’s Hill on the morning of July 3, 1863 – fighting for the Confederacy. Another brother, William, fought for the Union but was not present at Gettysburg. Julia and her sister, Annie, lent their aid in nursing the wounded after the battle. Julia spent many hours assisting in amputations and the strong odor of ether, used to render the wounded soldier unconscious, soon made her ill. She also worked with embalming the dead, and that fluid also released toxicity. Julia was one of the Gettysburg women who soon became seriously ill from the effects of both liquids, which affected her nervous system and her circulatory system. She was never in good health after Gettysburg. Julia moved to New Jersey and married John Willever, but died soon afterward, in 1868, at the age of 21. Her death certificate marks the cause of death as “ the effects of embalming fluid that she was exposed to while serving as a nurse after the Battle of Gettysburg.”