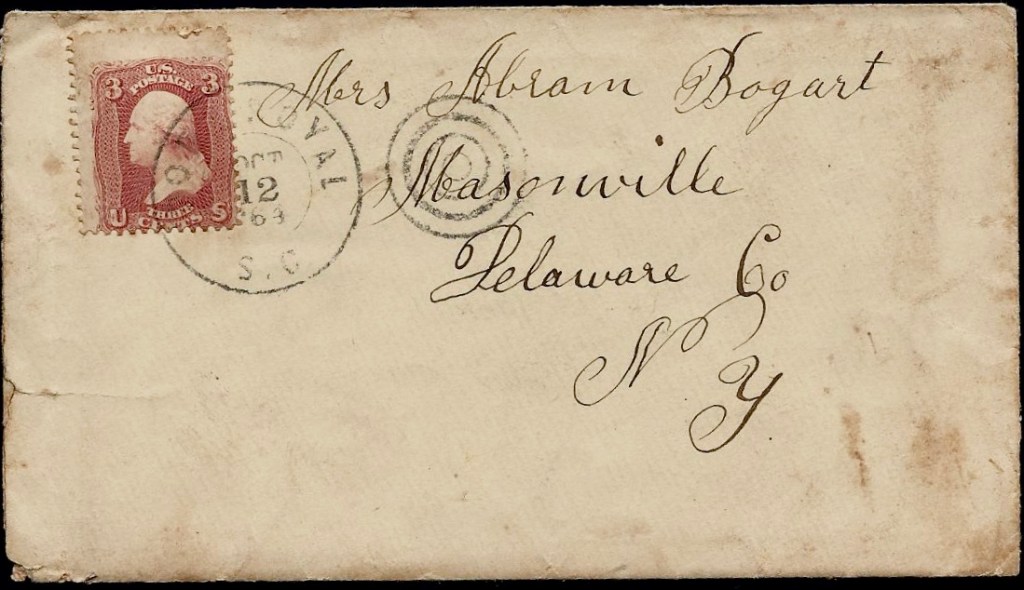

The following letters were written by 40 year-old Abram Bogart (1825-1899) of Masonville, Delaware county, New York. Abram enlisted on 15 August 1862, at Sidney, Delaware County, for a period of three years and was mustered into the 144th New York Infantry Regiment, Co. I, on 27 September 1862. At the time of his enlistment he was 37 years old and was described as being a light-haired, blued-eyed farmer who stood 5 feet 4 inches tall. He was transferred to Co. K, on 15 October 1862. He mustered out with his company on June 25, 1865, at Hilton Head, S.C. After the war he returned home where he worked as a farmer with his wife Mary, and their three children.

The greatest numbers of casualties incurred by the regiment was during its service on Folly Island during the siege of Charleston, South Carolina. Contaminated drinking water caused severe illnesses amongst almost the entire regiment. So many men became ill with diarrhea that a board of surgeons was appointed to determine which men would be eligible for furloughs so that they could recover from the sickness. A convalescent camp was established at St. Augustine, Florida where many of the men spent their illness-caused furloughs. The regiment lost 217 men during service: 2 officers and 37 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 4 officers and 174 enlisted men by disease. The most frequent causes of death listed for the many members of the Regiment who died of disease included typhoid fever and chronic diarrhea.

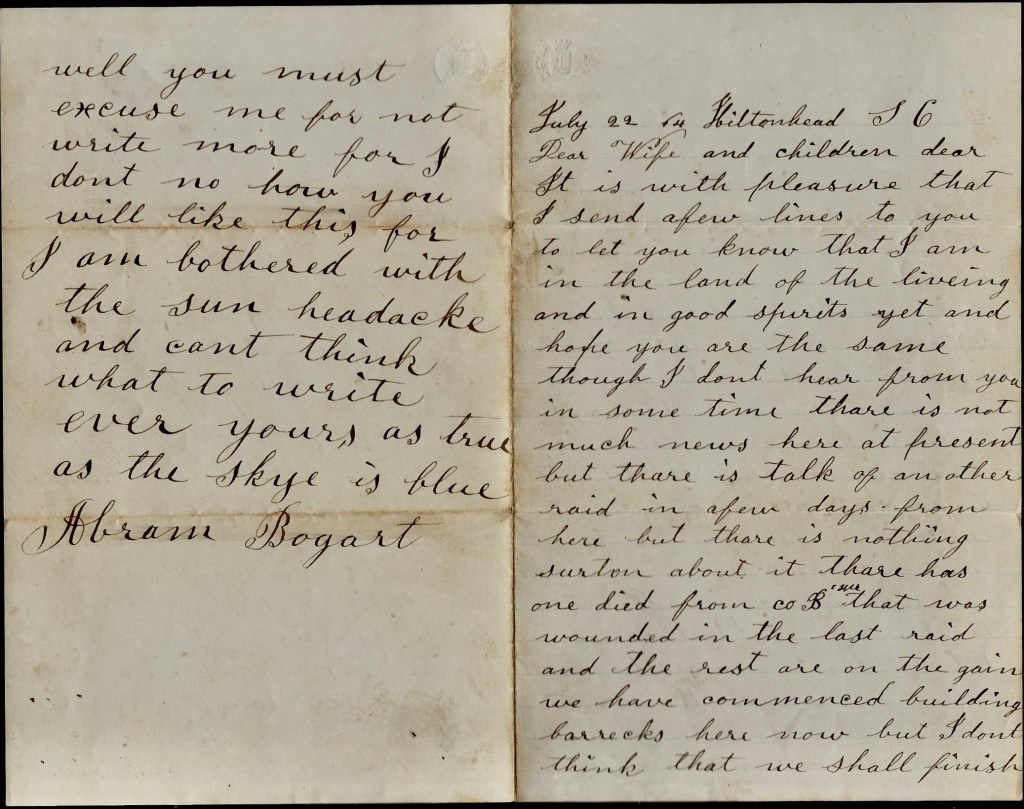

Letter 1

July 22, 1864

Hilton Head, South Carolina

Dear Wife and Children,

It is with pleasure that I send a few lines to you to let you know that I am in the land of the living and in good spirits yet, and hope you are the same though I don’t hear from you in some time. There is not much news here at present, but there is talk of another raid in a few days from here, but there is nothing certain about it. There has one died from Co. B that was wounded in the last raid and the rest are on the gain.

We have commenced building barracks here now but I don’t think that we shall finish them for I don’t think we shall stay so long in one place. But some think that we shall winter here and I am sure I don’t care where we stay for it is the same to me whether on the march or in camp if I can hear that you are all well at home. So you must write as often as you can and tell what the neighbors are doing if you can for I should like to hear what is going on around there. And tell James to write if he can, or send me a weekly paper instead for they come right through when sent from the North.

Today is Monday, the 25th of July, and the same monotony in camp as usual is the case. I want you to take good care of the children and not send Cassie to school when she is not well enough to stand it for you know that they are our all in this world and they are entrusted to your care and comfort now, and you must be their guardian while on earth. And if they are called by death, you will know that it is all right. And also take care of yourself for it is better to live in poverty than in contentions, and the way of the wicked for their paths are strewn with thorns. And a contented mind is a continual feast no matter what our rations are, [even] ff it is a cup of water and dry hardtack and raw meat.

Well you must excuse me for not writing more for I don’t know how you will like this for I am bothered with the sun headache and can’t think what to write. Ever yours as true as the sky is blue. — Abram Bogart

Letter 2

Hilton Head, South Carolina

August 5, 1864

Dear Wife and Children,

It is with pleasure that I write to you to let you know that I am in the land of the living, and have tolerable good health at this time, and hope you are the same. You spoke in your letter that you had got some things to take care of and a garden to hoe, and how do you get along with it? And have you any chickens to eat this fall? And [you said] that you had rather hear that I was killed in battle than to hear that I was under arrest. Now I had rather serve my time out in some fort than be in this aristocratical army for it gets worse every day for we have got to have everything scoured and polished til you can see your [face] in it. And the Rebs can see our guns glisten as far as they can see us, and they know right where to shoot, and we can’t see them—only by their smoke—and we can’t sight our guns for they glisten so that it hurts our eyes and draws the sun so that we are getting sun struck when we ought to be the best, and then have to retreat to save ourselves and sick. There is as many again die here as gets killed in battle on that account and that is the reason we get sick of it. And the officers put on airs and strut about and find fault with the men and punish them for nothing, but when it goes to a court martial, then they are done for.

I am back to the company and nothing found against me after laying off from the 21st June til the eighth of August, and now I am almost a mind to try them now, but the old saying is the more that you stir a turd, the worse it stinks, so I think that I shall let them be this time. So you see how it is now and I don’t want you to feel bad for I have told you that when the worst comes to worst, that I should look out for myself and so I shall never fear.

I don’t see why my folks don’t write to me anymore, or have they got ashamed of me. If so, just let me know it for I don’t want to think that I have got friends when I haven’t got any for I hate assumed friends anywhere, for that is the great curse in this war, and when we are out of sight, they are against us. And I think it is time there was a sifting of the wheat and see who is right and who is wrong, for it is in the army as it is in the country, when they are with you, they are friends, and when you are away, they will talk about you and find fault with what you do. And it is just so with the generals. One finds fault with the other, and that is the way with this army down here. And then they say that they can’t depend on the troops, and the private has it after all.

I should like to have you see some of the slaves as they are on the plantations with all their notions for they have been made to believe that the Yankees have horns and tails like an ox and are great thieves and robbers and destroy everything where they go. And to see them roll their eyes when they see the Yankee soldiers come around the plantations and the little ones hide and then come to their Ma and say I don’t see any horns and some of them are as pretty as a nigger can be—slim and straight—and they hain’t over black around here, but are very timid and keep off as far as they can.

Well, you say that if I want to say anything to you, I must put it on a separate piece of paper. Well, I should like to know if you are willing that I should get breakfast for you some Sunday morning and how you would pay for it and whether to or not be particular about it if I should take out my pipe to spit after eating for I am getting awfully in want by this time and would like to know how you stand it for want of help by this time, or have you got a past want in those things pertaining to nature. Well, I guess you will think that I have got a foolish spell. So good by, — Abram Bogart

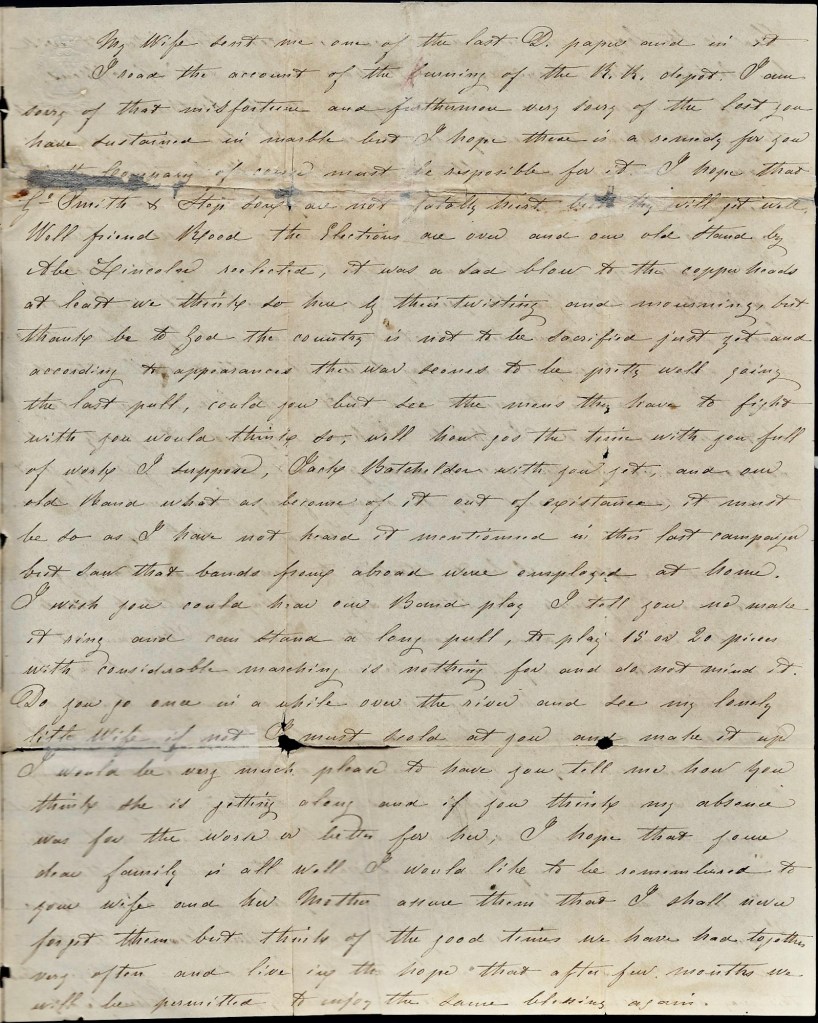

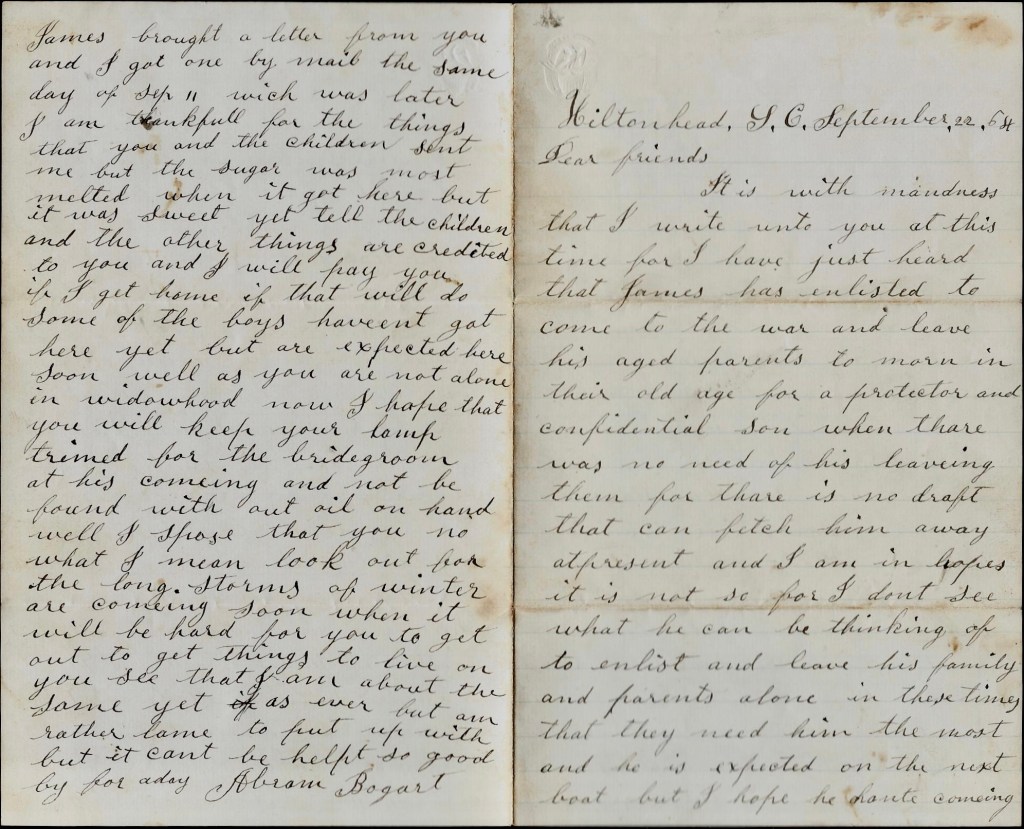

Letter 3

Hilton Head, South Carolina

September 22, 1864

Dear Friends,

It is with madness that I write unto you at this time for I have just heard that James has enlisted to come to the war and leave his aged parents to mourn in their old age for a protector and confidential son when there was no need of his leaving them for there is no draft that can fetch him away at present. I don’t see what he can be thinking of to enlist and leave his family and parents alone in these times that they need him the most and he is expected on the next boat, but I hope he ain’t coming.

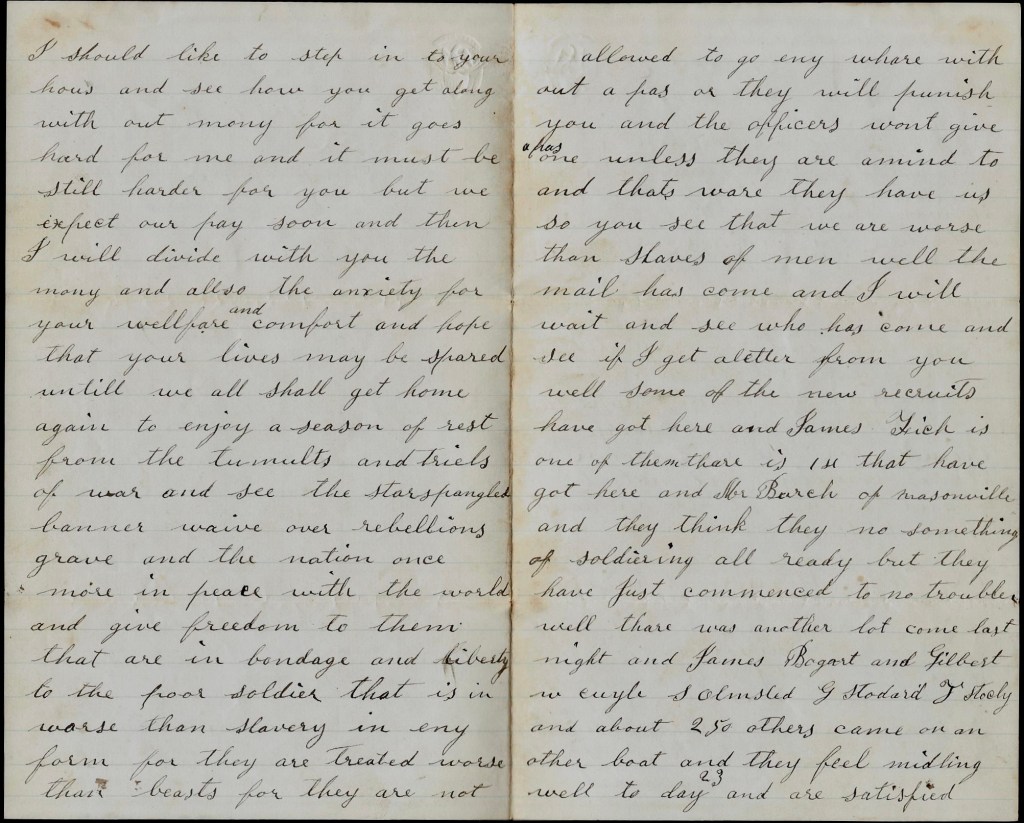

I should like to step in your house and see how you get along without money for it goes hard for me and it must be still harder for you. But we expect our pay soon and then I will divide with you the money and also the anxiety for your welfare and comfort and hope that your lives may be spared until we all shall get home again to enjoy a season of rest from the tumults and trials of war, and see the Star Spangled Banner wave over rebellious graves and the Nation once more in peace with the world, and give freedom to them that are in bondage and liberty to the poor soldier that is worse than slavery in any form for they are treated worse than beasts, for they are not allowed to go anywhere without a pass or they will punish you, and the officers won’t give a pass unless they are a mind to and that’s where they have us. So you see that we are worse than slaves.

Well the mail has come and I will wait and see if I get a letter from you. Well, some of the new recruits have got here and James is one of them, and Mr. Burch of Masonville, and they think they know something of soldiering already, but they have just commenced to know trouble. Well, there was another lot come last night and about 250 others came on another boat and they feel middling well today (23rd) and are satisfied. James brought a letter from you and I got one by mail the same day of September 11th. I am thankful for the things that you and the children sent me, but the sugar was most melted when it got here, but it was sweet yet. Tell the children and the other things are credited to you and I will pay you if I get home if that will do. Some of the boys haven’t got here yet, but are expected here soon. Well, as you are not alone in widowhood now, I hope that you will keep your lamp trimmed for the bridegroom at his coming and not be found out oil on hand. Well, I suppose that you know what I mean. Look out for the long storms of winter are coming soon when it will be hard for you to get out to get things to live on.

I am about the same yet as ever but am rather lame to put up with but it can’t be helped. So good bye for a day, — Abram Bogart

Letter 4

Hilton Head, South Carolina

October 8th 1864

Dear Wife and Children,

It is with pleasure that I send a few lines to you to let you know that I am here and am like to stay for what I see, but James and Gilbert are in the First N. Y. Engineers Regiment, and a lot more that enlisted for the 144th and I wish that I was there too. And James is gone to the general hospital so I am left alone again and I am glad that they had some good luck in getting out of the regiment for they seen enough to convince them to get out if they could and they improved the chance for it was no place for them here.

Silas Olmsted is in the hospital and the rest from our place are well for what I know. Franklin Stoddard and [John W.] Hoskin are in the tent with me and the rest from there are in Co. H and B, what are here, and the rest that are left behind have got to go in another regiment. So you can see what they get by enlisting for the 144th. They have got to go just where they send them.

Sunday. I have been down to the hospital to see James and he is on the gain I think, and is very contented and thinks he is in a good place now, and has good care and Gilbert was to my tent so I guess that he is well and he thanks his stars that he is out of the regiment and has nothing to do with the 144th Heavy Artillery which they never was nor never will be.

Tuesday morning and I have just come off picket and it was rather cold in the night for this place, but I got warm as soon as I heard that there was a letter here for me, and I got it before I unharnessed myself and read it, and it was a joy to hear that you was all well at that date. But you didn’t say anything about James’s folks nor Gilbert’s, and I guess you had better next time for I want to know what [they] think of being alone this winter. And I should like to know which is the loneliness of you all and how you get along. And tell Jeremiah that he must do the best that he can for the widows that are left to his care.

There was a lot more soldiers came here today for our regiment, but they were turned over to the engineers for them to manage. They felt rather bad to be turned off, but I think they will get over it in a few days when they have a chance to see how it is here, and what they have to do, and how they are treated [by] their officers.

You must not try to do too much and get sick yourself for then who would take care of the children, much less yourself. It is better to have less and health than to not enjoy the fruit of your labor after you have got it and try to get along as well as you can this winter for I think the war is almost done. But it will take some time to get around. But the fighting is about done. The deserters that come in now say it is and they come in by the hundreds everyday with us and more in other places. There was over a hundred come from Charleston last week.

This from your ever loving, — Abram

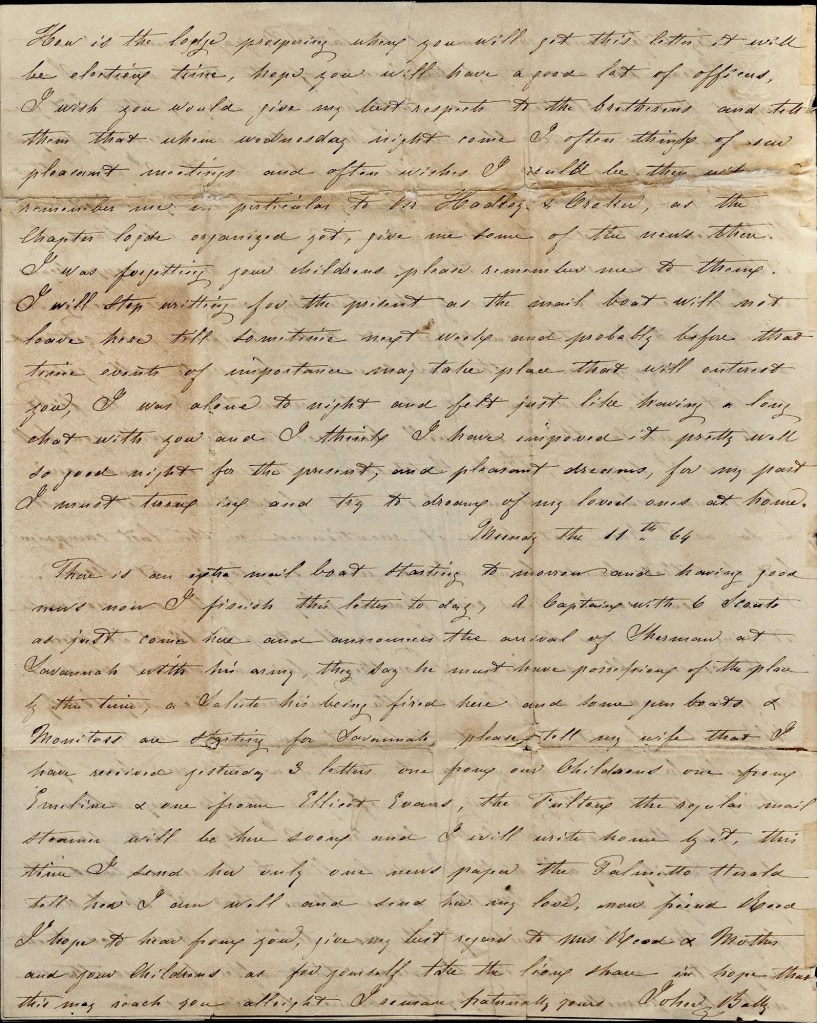

Letter 5

Hilton Head, South Carolina

December 21, 1864

Dear Wife and Children,

It is with prospects of hearing from you that I write a few lines to let you know that I have not forgotten you nor yours and hope that these few lines will find you in good health and spirits. My health is very good but my lameness is quite bad for a few days so that I have to rest for a few days from guard and the rest of the boys are on duty all the time while the regiment are out. And how much longer they will stay, we do not know.

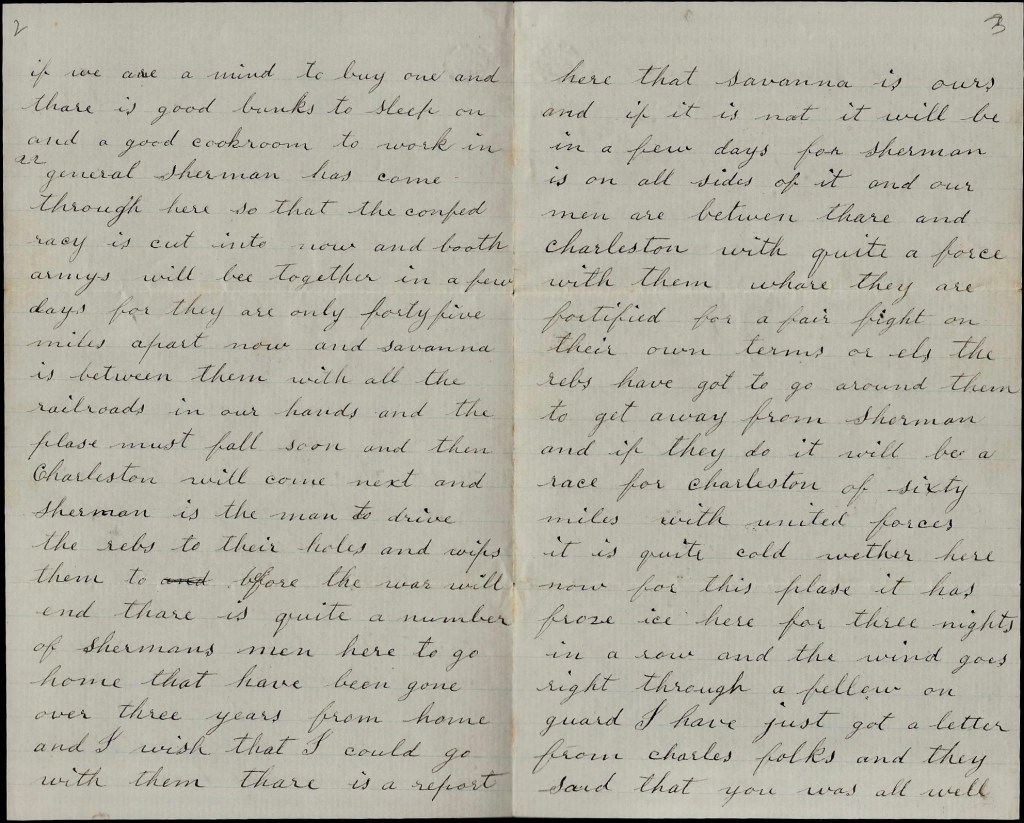

We like our duty here very much and we have good quarters to stay in. Our rooms are for eight to stay in where we can have a stove in if we are a mind to buy one and there is good bunks to sleep on and a good cookroom to work in.

General Sherman has come through here so that the Confederacy is cut in two now and both army’s will be together in a few days for they are only forty-five miles apart now and Savannah is between them with all the railroads in our hands and the place must fall soon, and then Charleston will come next, and Sherman is the man to drive the Rebs to their holes and whip them too before the war will end. There is quite a number of Sherman’s men here to go home that have been gone over three years from home and I wish that I could go with them.

There is a report here that Savannah is ours and if it is not, it will be in a few days for Sherman is on all sides of it and our men are between there and Charleston with quite a force with them where they are fortified for a fair fight on their own terms or else the Rebs have got to go around them to get away from Sherman. And if they do, it will be a race for Charleston of sixty miles with united forces.

It is quite cold weather here now for the place has frozen ice here for three nights in a row and the wind goes right through a fellow on guard. I have just got a letter from Charles’ folks and they said that you was all well. James was here yesterday and he says that he feels better than he has for two years, and I think that he looks better than I have seen him in that time, and I went up to the dock with him and in the town and he out walked me all together and would [have] went over to nigger town if I could stand it, but I could not, so we went into a saloon and had some pancakes and [mo]lasses and came home. And today I am in my quarters lamer than ever. But I shall get over it in a few days and go at it again.

Sunday. The island is covered with troops from Sherman’s men that are waiting to go home and they have brought a lot of Rebel prisoners here with them for us to take care of and some are sick and some are wounded and look hard. I went down and saw James today and he has got some Rebs to take care of.

This is a new town built since the war began and is a military town and used for that purpose and is fortified with entrenchments and stockade posts ten feet high on the outside and the stockade is six miles long with three gates to pass out and in that are guarded day and night and no one can pass without a pass and the entrenchments mount about forty guns besides the forts that mount sixty guns more. And we do the guard duty in the entrenchments and dock, and headquarters guard, and then there is forts on the outside and pickets there besides ours some twelve or fifteen miles from here, but this is the main boat landing for this department and the whole South and everything is first fetched here and then sent to other posts in the South so it makes a business place of [it] here and we have mail every week, here from New York in three days, and Rebel news when we can get it, and we have to pay ten cents for New York papers. I should like to get a weekly but I am too poor to take one at present and how is it with you? Do you take a paper? If not, try and get one if you can spare the money for it is company for you these long nights to read, and you can tell how the war goes in some places. And you can send one to me now and then to wile away the hours for papers come when letters don’t sometimes.

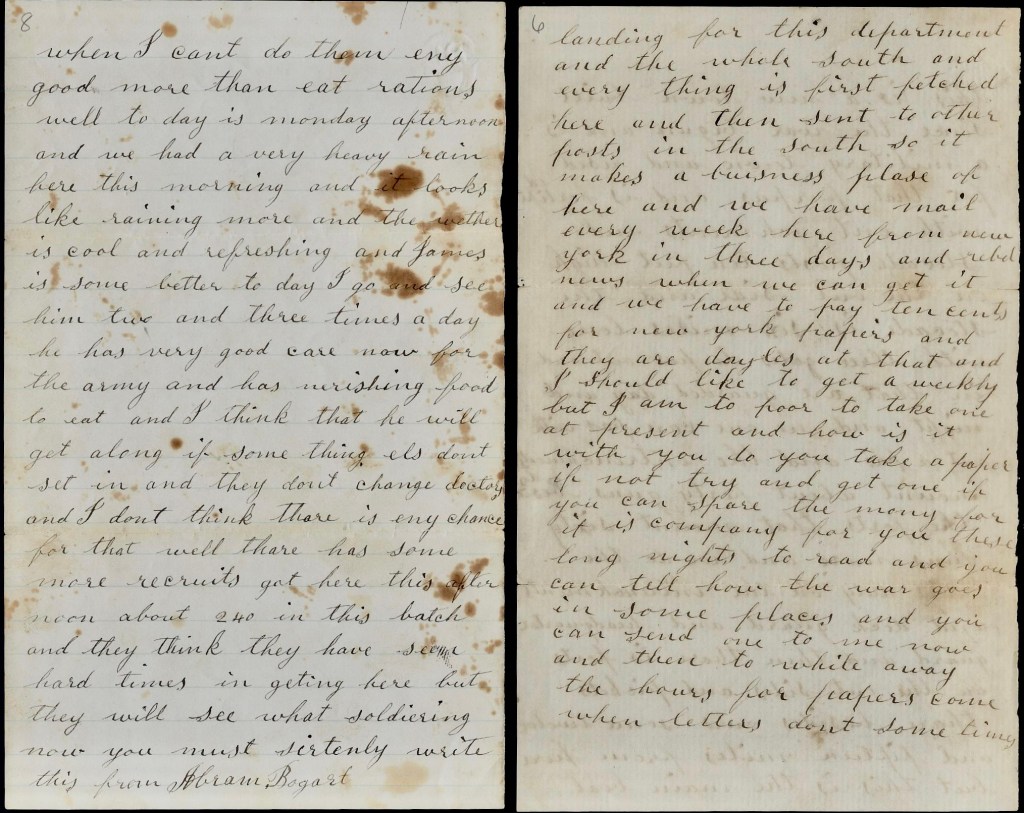

Sunday evening and I thought that I would send a few lines more to you to let you know what rumor is in camp. They say that a vessel has sunk loaded with soldiers for this place and all was lost onboard but there is no certainty about it. And they say that I am going to be transferred to the Invalid Corps but I don’t believe that neither till I see it for I am not fit for duty and have not done much for the last year, though my health is tolerably good yet. And I guess that I can worry out another year in the same way if they want I should, and live, but it is hard to stay here when I can’t do them any good more than eat rations.

Well, today is Monday afternoon and we had a very heavy rain here this morning and it looks like raining more and the weather is cool and refreshing and James is some better today. I go and see him two and three times a day. He has very good care now for the army has nourishing food to eat and I think that he will get along if something else don’t set in and they don’t change doctors and I don’t think there is any chance for that. Well there has some more recruits got here this afternoon about 240 in this batch and they think they have some hard times in getting here but they will see what soldiering is. Now, you must certainly write.

This from Abram Bogart

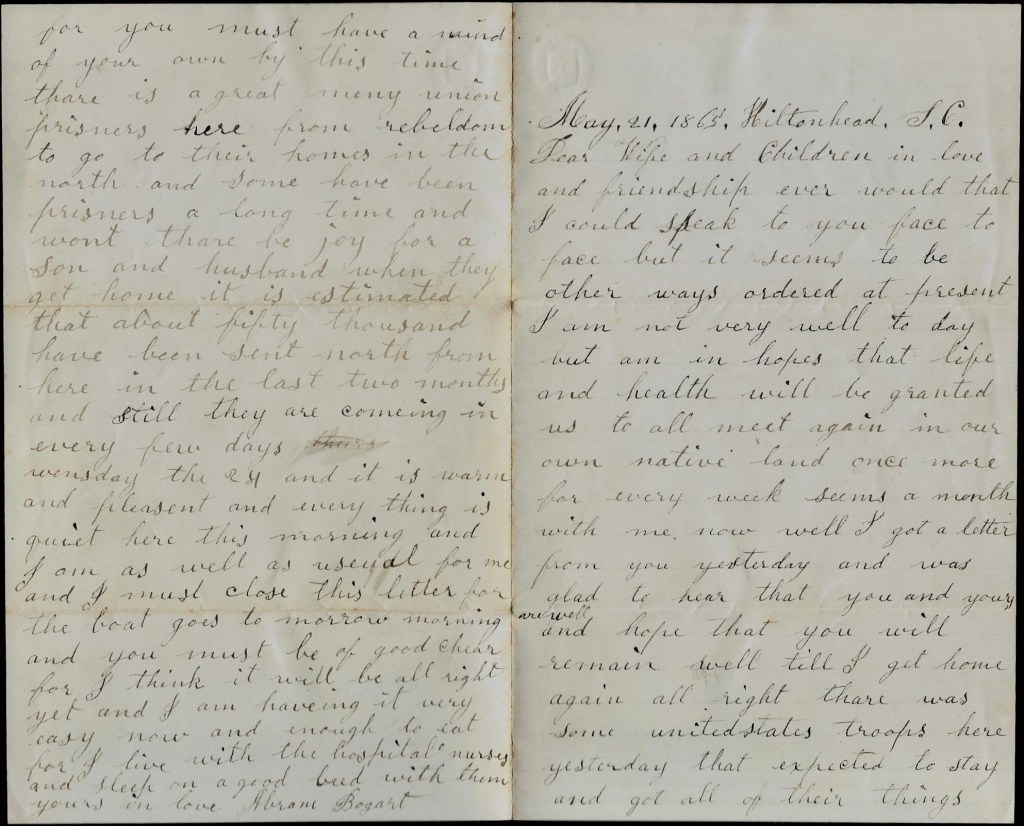

Letter 6

Hilton Head, South Carolina

May 21, 1865

Dear Wife and Children,

In love and friendship ever would that I could speak to you face to face, but it seems to be other ways ordered at present. I am not very well today but am in hopes that life and health will be granted us to all meet again in our own native land once more for every week seems a month with me now.

Well, I got a letter from you yesterday and was glad to hear that you and yours are well and hope that you will remain well till I get home again all right. There was some United States troops here yesterday that expected to stay and got all of their things in the yard and then was ordered to Florida and left before night again and when there will be others come, we don’t know, but am in hopes it will be soon. There is every sort of rumor here as well as there about our going home soon. I have not heard from James nor Gilbert since I last wrote to you for it is about sixty-five miles from here to Charleston and we don’t have to go there since Johnston surrendered. There is no more soldiers going to their regiments, but go to New York instead of coming from there here, but it is all the other way and I am glad of it for my part so that some can get home [even] if I can’t. But our turn will come by & by, I think, for there is a good deal of talk about going and I think we shall come between this and July. There is some a going on this boat that are unable to do anything here.

I should like to know if there is any chance for you to sell the place at a pretty high price and what you think of living in the South where the winter is not so cold and as for the summer, I don’t think there is much difference in the heat and the land is richer here too and easier to work. And everything will grow here that will grow there and some things that won’t. But you must make your own choice for you must have a mind of your own by this time. There is a great many Union prisoners here from Rebeldom to go to their homes in the North and some have been prisoners a long time and won’t there be joy for a son and husband when they get home. It is estimated that about fifty thousand have been sent North from here in the last two months and still they are coming in every few days.

Wednesday the 24, and it is warm and pleasant and everything is quiet here this morning and I am as well as usual for me and I must close this letter for the boat goes tomorrow morning and you must be of good cheer for I think it will be all right yet and I am having it very easy now and enough to eat for I live with the hospital nurses and sleep on a good bed with them. Yours in love, — Abram Bogart