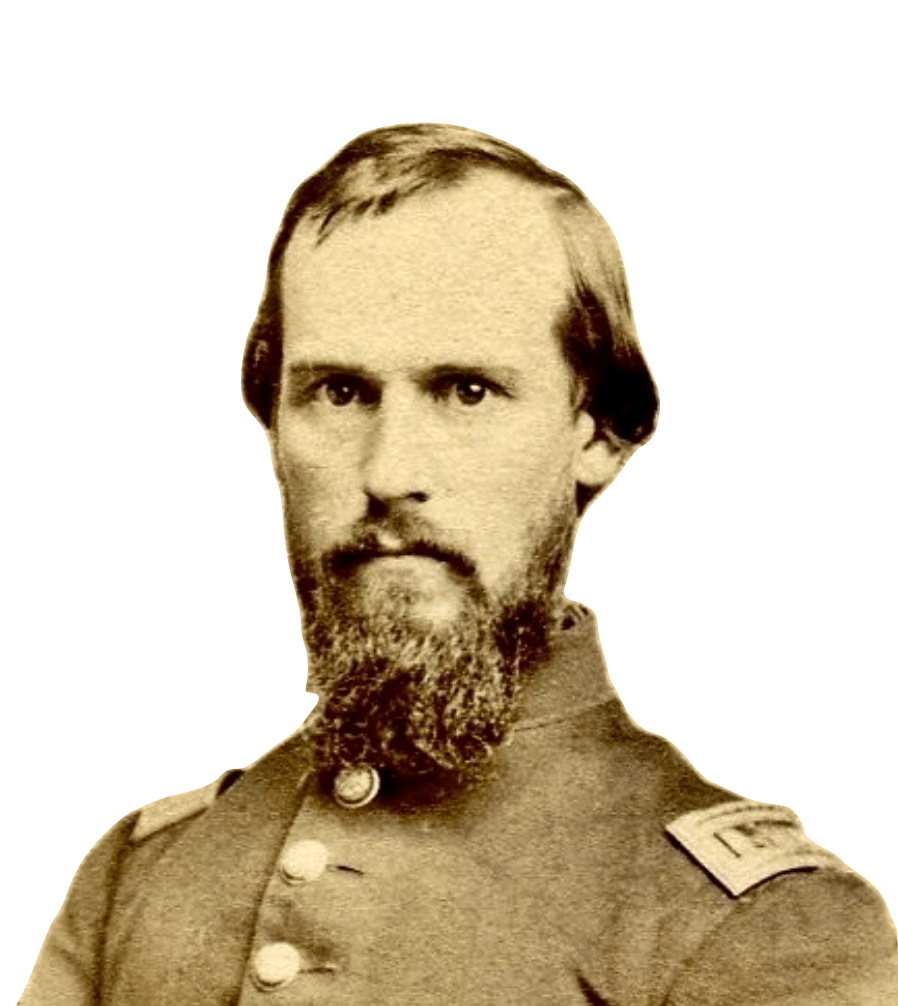

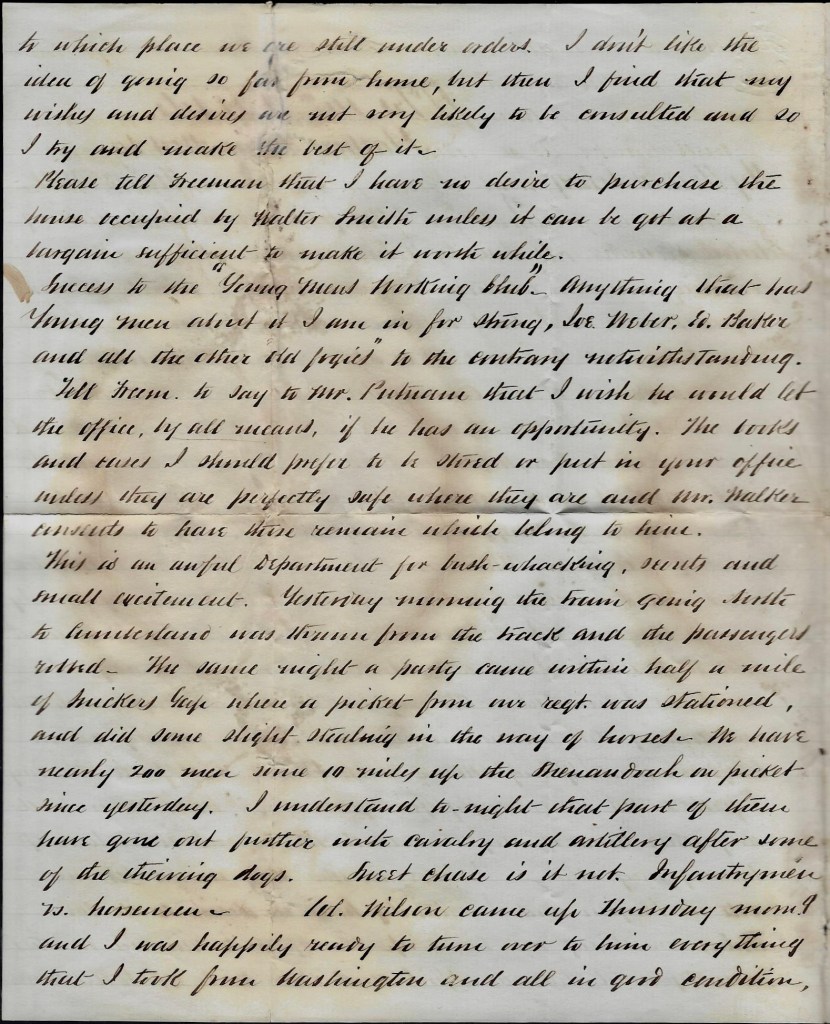

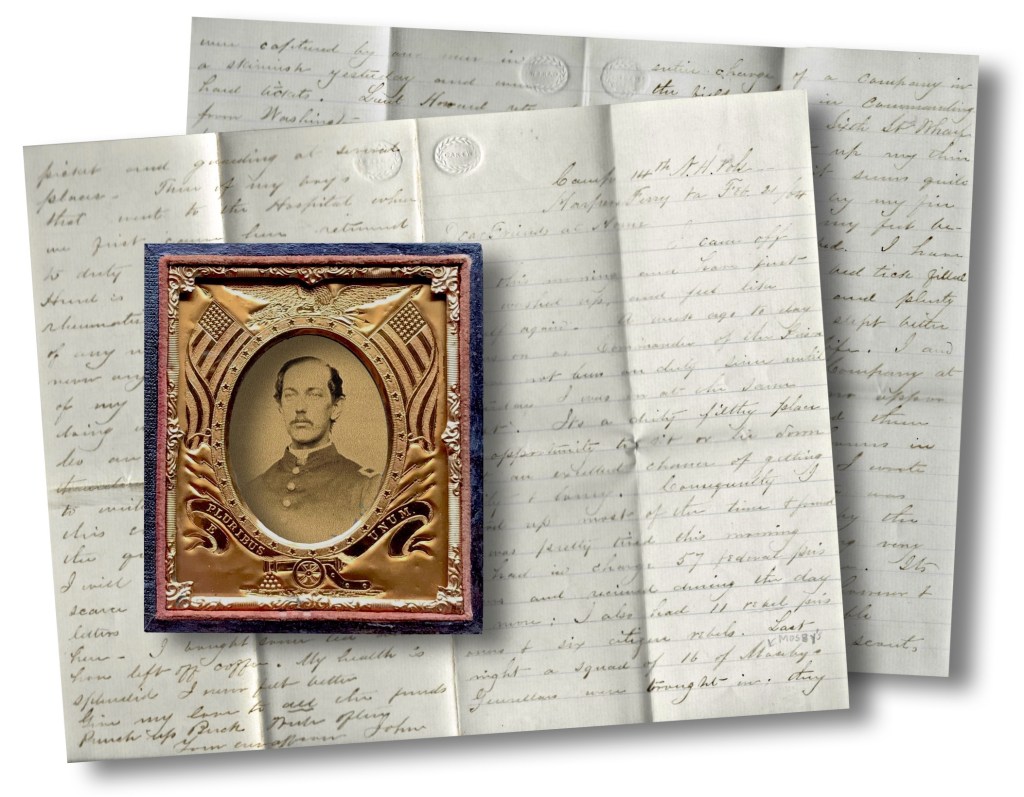

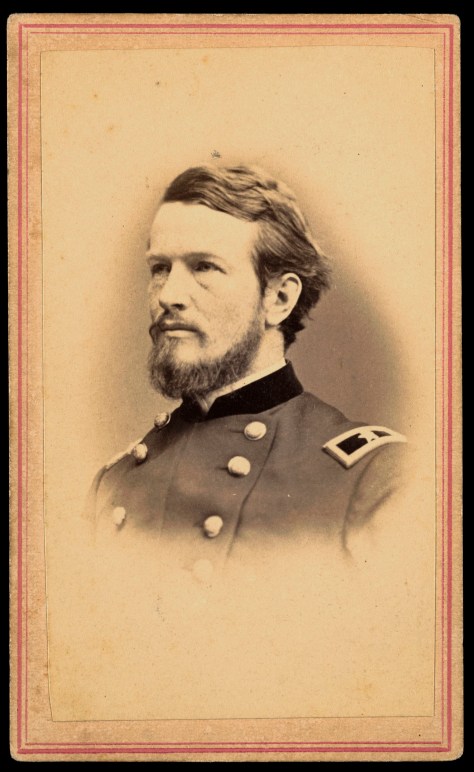

The following letter was written by Samuel Augustus Duncan who began his service in the Civil War as Major of the 14th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment and was later commissioned the Colonel of the 4th U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry Regiment. He was brevetted Brigadier General, US Volunteers on October 28, 1864 for “gallant and meritorious services in the attack upon the enemy’s works at Spring Hill, Va.” On March 13, 1865 he was brevetted Major General, US Volunteers for “gallant and meritorious services during the war.” After the end of the conflict he became a patent lawyer, and served as Assistant United States Commissioner of Patents from 1870 to 1872.

Duncan’s letter is primarily focused on the treatment and care provided to Col. Alexander Gardner (1833-1864), 14th New Hampshire Infantry, following his mortal wounds sustained at the Battle of 3rd Winchester (or Opequon) on September 19, 1864. It can be inferred from the correspondence that the Gardner family harbored resentment toward the regimental surgeon, Dr. William Henry Thayer, for his inability to preserve the colonel’s life. Nevertheless, Duncan offers a robust defense of the doctor’s decisions and actions during in the aftermath of the battle.

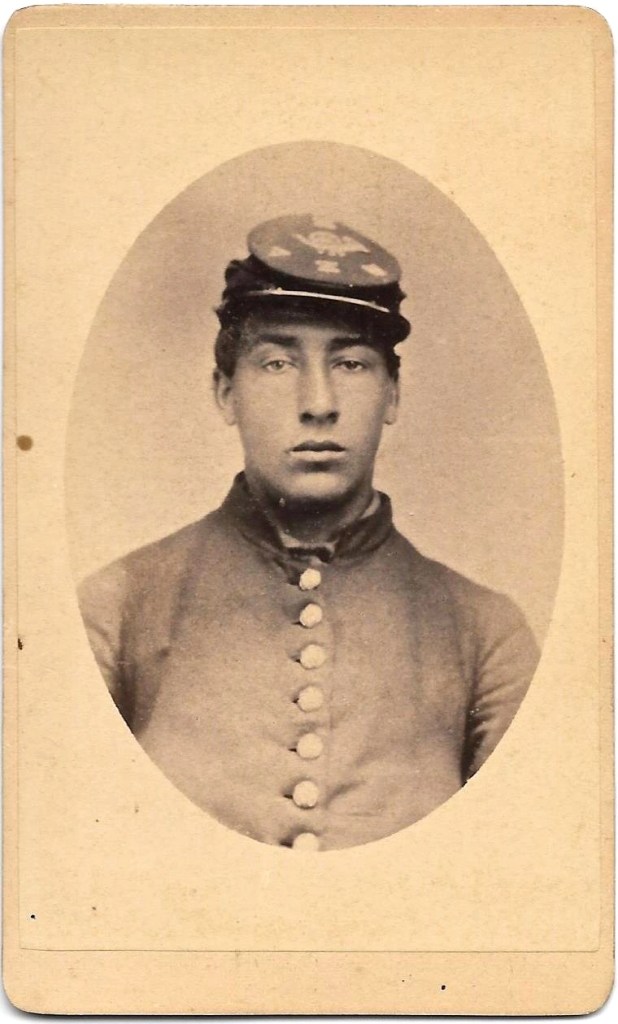

Samuel wrote the letter to James “Graham” Gardiner who served as an adjutant to Samuel in the 4th USCT but who resigned following the death of his brother Alexander as he was the only surviving son in the family.

See also—1864: Alexander Gardiner to Ira Colby

Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

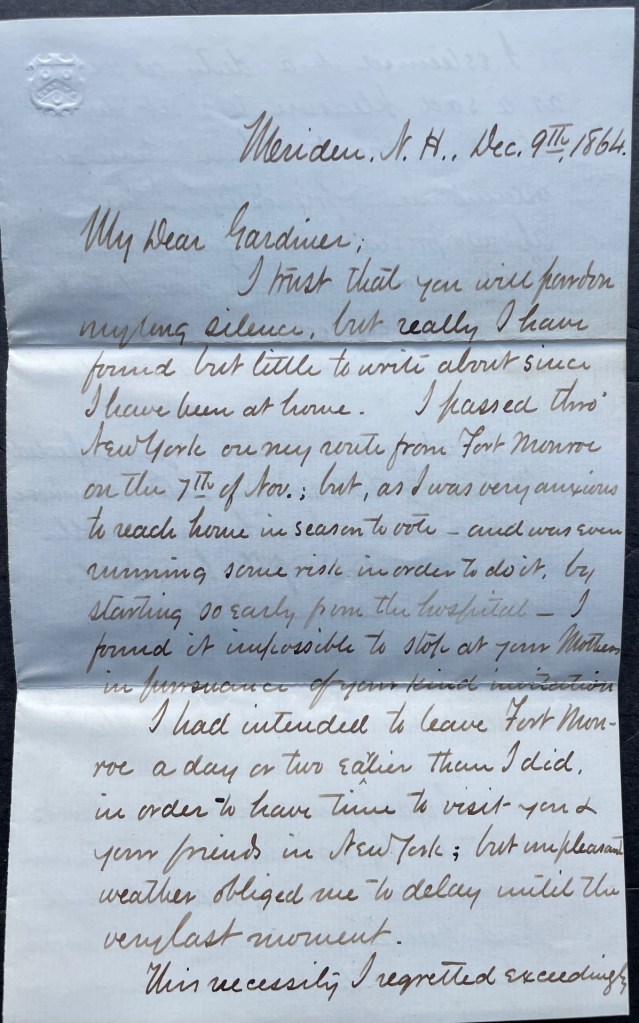

Meriden, New Hampshire

December 9th 1864

My dear Gardiner,

I trust that you will pardon my long silence but really I have found but little to write about since I have been at home, I passed through New York on my route from Fort Monroe on the 7th of November, but as I was very anxious to reach home in season to vote—and was even running some risk i order to do it by starting so early from the hospital—I found it impossible to stop at your Mother’s in pursuance of your kind invitation. I had intended to leave Fort Monroe a day or two earlier than I did in order to have time to visit you & your friend in New York, but unpleasant weather obliged me to delay until the very last moment. This necessity I regretted exceedingly as I esteemed it a duty, as well as a sad pleasure to visit the afflicted friends of him whose acquaintance & friendship I had always prized most highly while he lived, and whose memory now that he has been called away is treasured up among the most valued recollections of the past.

Do not fail to extend to your respected Mother, to that stricken sister with whose acquaintance I am honored, & to the other members of the household, renewed assurances of my profoundest sympathy with them in the great sacrifice which the country called for in the life of Col. Alexander Gardiner.

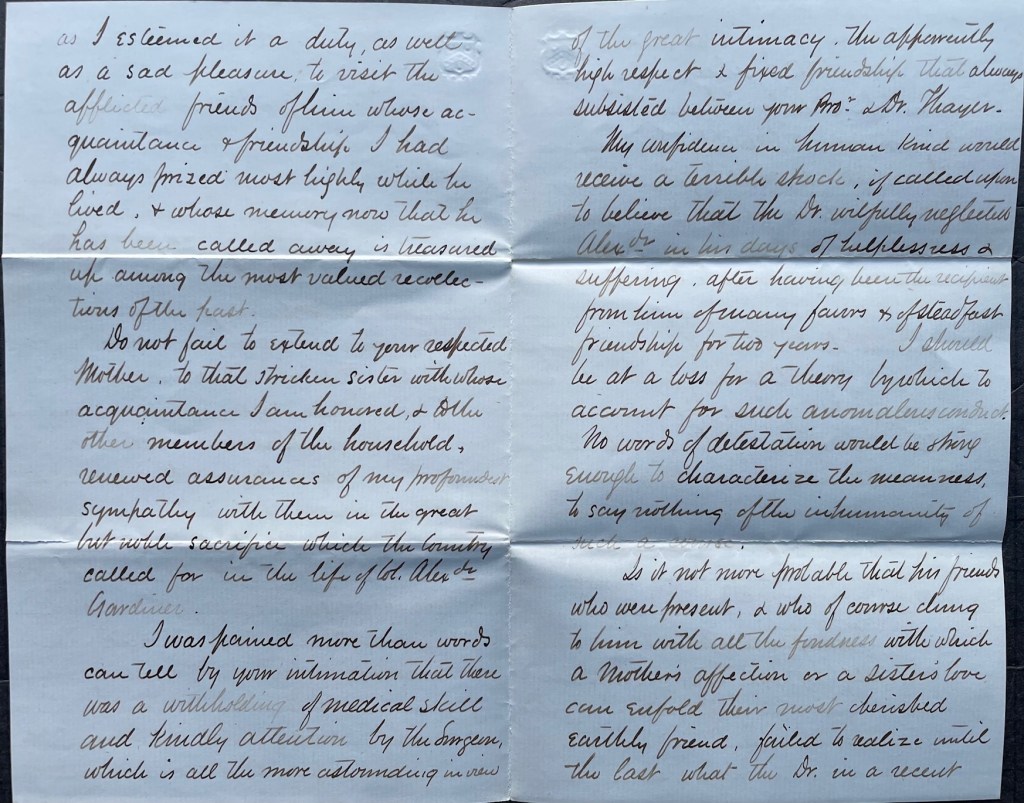

I was pained more than words can tell by your intimation that there was a withholding of medical skill and kindly attention by the surgeon which is all the more astounding in view of the great intimacy, the apparently high respect & fixed friendship that always subsisted between your brother and Dr. [William Henry] Thayer. 1 My confidence in human kind would receive a terrible shock if called upon to believe that the Dr. willfully neglected Alexander in his days of helplessness & suffering after having been the recipient from him of many favors and of steadfast friendship for two years. I should be at a loss for a theory by which to account for such anomalous conduct. No words of detestation would be strong enough to characterize the meanness to say nothing of the inhumanity of such a course.

Is it not more probable that his friends who were present & who of course clung to him with all the fondness with which a Mother’s affection or a sister’s love can enfold their most cherished earthly friend, failed to realize until the last what the Dr. in a recent letter to me says it was apparent to himself and other skillful surgeons whom he called in council from the first, viz. that the Colonel’s wounds were necessarily of a mortal character. and , failing to realize this fact, easily and almost naturally formed wrong ideas respecting the course of treatment which was actually adopted, and which was sanctioned by the consulted surgeons of acknowledged skill.

Of course this would not excuse any inattention or lack of friendly ministration that could prolong life or assuage pain & could be given consistently with the manifold imperative duties that at such a time & in such an emergency tax a surgeon’s time and energies to their utmost capacity.

I can but hope that you and all your friends in forming your final estimates in this matter will give due prominence to the multifarious and distracting cares that fall to a surgeon’s lot after a great battle as well as to the repeated consultations which Dr. Thayer had about your brother with other prominent surgeons, and especially to the peculiarly intimate relation which had always subsisted between the surgeon and his patient, and it would be a great relief to me, I assure you, could I know that such a belief at last obtains among those who were present by your brother’s bed, as will notdo violence to thoserelations of intimacy and warmest friendship.

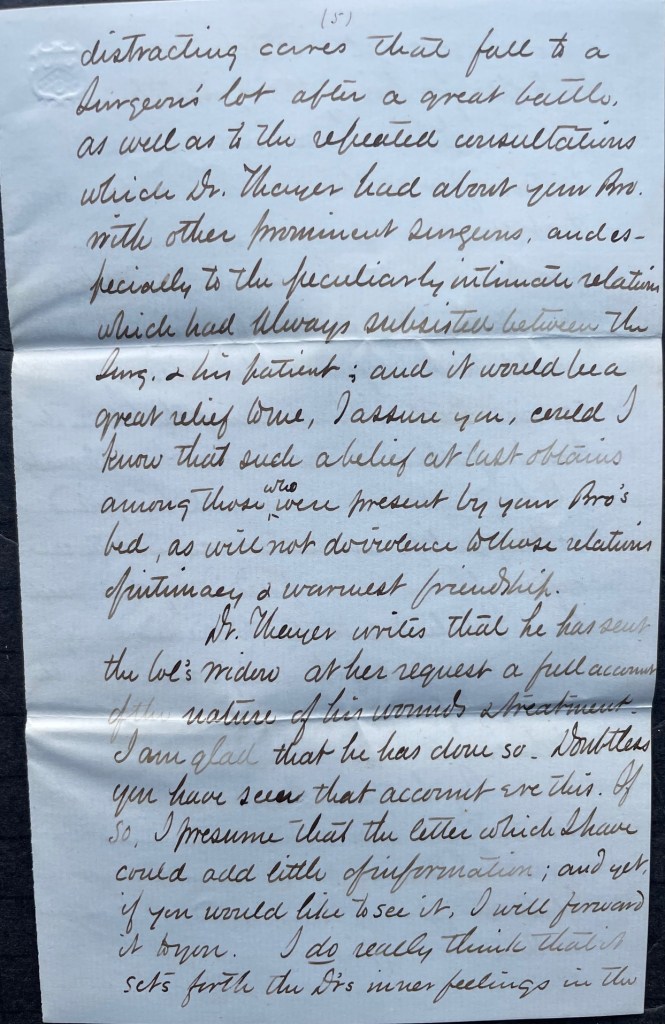

Dr. Thayer writes that he has sent the Colonel’s widow at her request a full account of the nature of his wounds & treatment. I am glad that he has done so. Doubtless you have seen that account ere this. If so, I presume that the letter which I have could add little of information, and yet if you would like to see it, I will forward it to you. I do really think that it sets forth the Dr.’s inner feeling in the case more explicitly than it might be proper for him to express them in a letter to Mrs. Gardiner, whom he has known for so short a time only. For that reason it may be a satisfaction to you to see it, as I assure you it has been to me, His assertion that he would have preferred dismissal from the service rather than leave the Colonel in the hands of others—that in fact he had made up his mind to remain with his friend so long as life remained, even at the sacrifice of his official position, if that need be, I believe entitled to credit. Might not such a resolve to weigh much in the forming of any judgment of the Dr.’s treatment of the case.

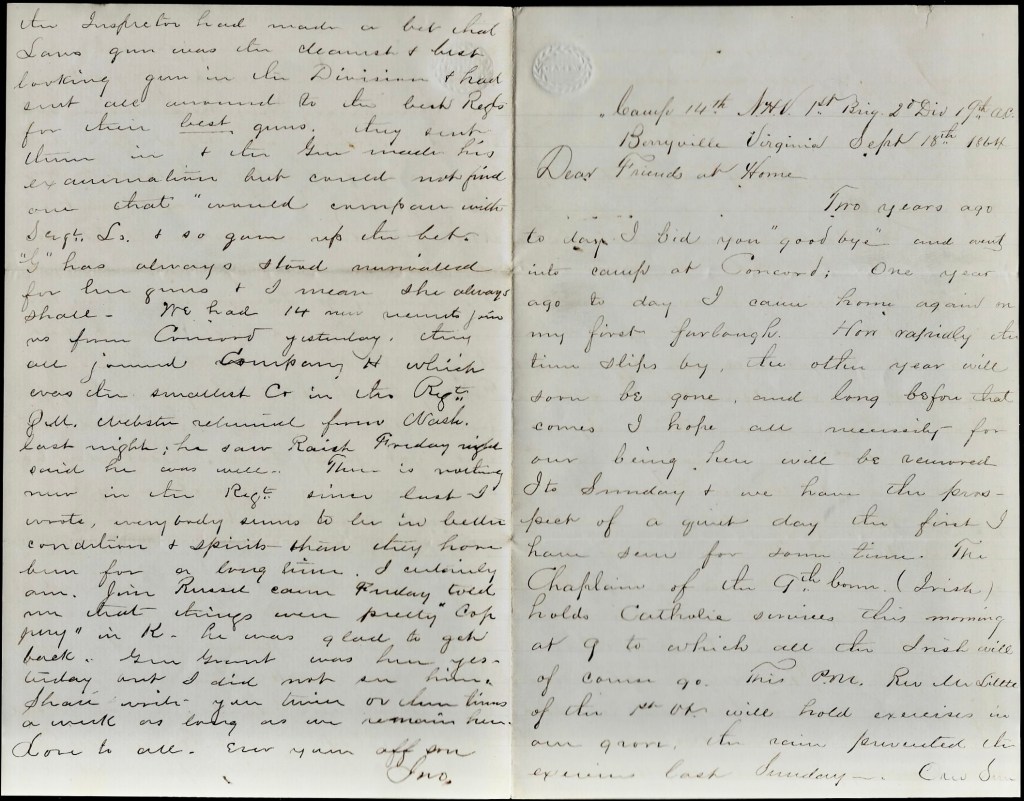

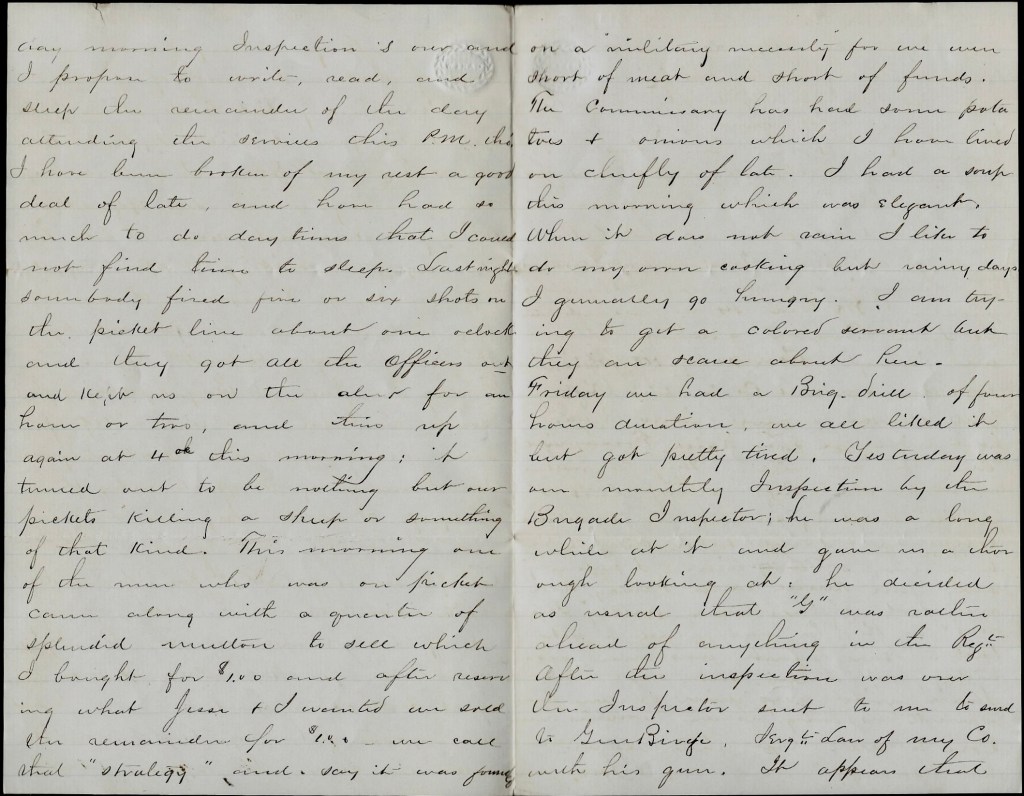

By this time I suppose that our Division has been incorporated into the 25th Corps under Gen. Weitzel. A recent letter from Col. [John Worthington] Ames [of the 6th USCT] represents him as well. Buckman is A.A.A.G.; Appleton of the 4th A.A.A. G.; Chamberlain of the 6th, Aide-de-Camp; and Spaulding of the 2nd Cavalry. Commissary–Wilber is still Quartermaster. The Colonel says that he recently rode over the battleground of New Market Heights [and] that everything there is so changed that he could hardly recognize the place. Troops are encamped all around, and all the trees in the vicinity have been felled and consumed. Gardiner, that was a terrible morning. It is not often that troops are called upon to enter such a murderous fire as was that. Even now I fail to comprehend the policy of putting us into it as we did go in. The affair might have been more successfully managed with less loss of life. Did you before leaving the Brigade hear this feature of it talked over any? I cannot see how any of us came out of that fight alive. How I ever got back from the skirmish line unharmed, mounted as I was, is a mystery. But believe me, my dear fellow, my thoughts that morning were not for myself half so much as for you. In the heat of the battle, I reproached myself, as my mind went out to that scene of suffering at Winchester and glanced at the probable fate hanging over your dear brother—if in fact he were then alive—for having allowed you to encounter the perils of that hour. Had harm befallen you, I know not how I could have reconciled your friends to my instrumentality in having drawn you into the service.

I would most gladly have spared you the anguish of that battle scene—anguish not from fear occasioned by appalling terrors that encompassed us, for I do not believe that you would shrink in the presence of danger however great, but by reason of your consciousness, the necessarily kindled into unwonted life, that after Alexander you would be the sole surviving son of your Mother on whom her hopes and affections would center more and more as other supports should be withdrawn. My own wound was forgotten in my joy at your safety.

And then I felt too that had a reasonably generous spirit been manifested by one who had the power, you would have been on your way to carry aid and comfort to your brother instead of being subjected to that ordeal. What pit ’tis that so much gaul should be found in men’s composition that they cannot lend a respectful ear to a reasonable request!

I cannot blame you should your recollections of your former superior officers be other than the most pleasant.

When I left the hospital (Nov. 5th), Lt. Pratt was very low. His case seemed hopeless. His wife was with him & was very calm & resigned, but Col. Ames now writes that Pratt has “weathered the storm” and will recover. I hope so, certainly, for he is a pleasant & companionable officer. But poor Vannays [?] we shall see no more. I think the commander–his staff of the 3rd Brigade—should be satisfied with their record of exposure to danger that day.

I am getting on well. Can walk a little in the house with a cane, but it is very slow and awkward work. Shall probably leave for Annapolis soon after the 1st of January, although it will be two months before I can return to the field.

[Col.] Ames [of the 6th USCT] writes that the “Canal” is a humbug still. It will not be near completion this year. It has among other novelties an old dredging machine sunk in the middle of it. Our men are all out of it. Thanks for that. It has cost Butler a good deal to make a Brigadier out of the Superintending Genius of the [Dutch Gap] Canal.

I hope that you are not suffering from the ague acquired on the James [river]. My diarrhea has troubled me much since I came home. Now, my dear Gardiner, if I can at any time be of any service to you, I am yours to command. Should you ever incline to reenter the service, I could doubtless assist you, and it would be a great pleasure to me to have you near me. My sorest regret connected with your resignation, aside from the sad circumstances that called for it. was that I should be deprived of your services and the pleasure of your society. It is but right that you should know that my regret was generally shared by those who had come to know you.

Again, please present my warmest regards to your friends. Letters from you will always be welcome. Cordially, your friend, — Sam’l A. Duncan

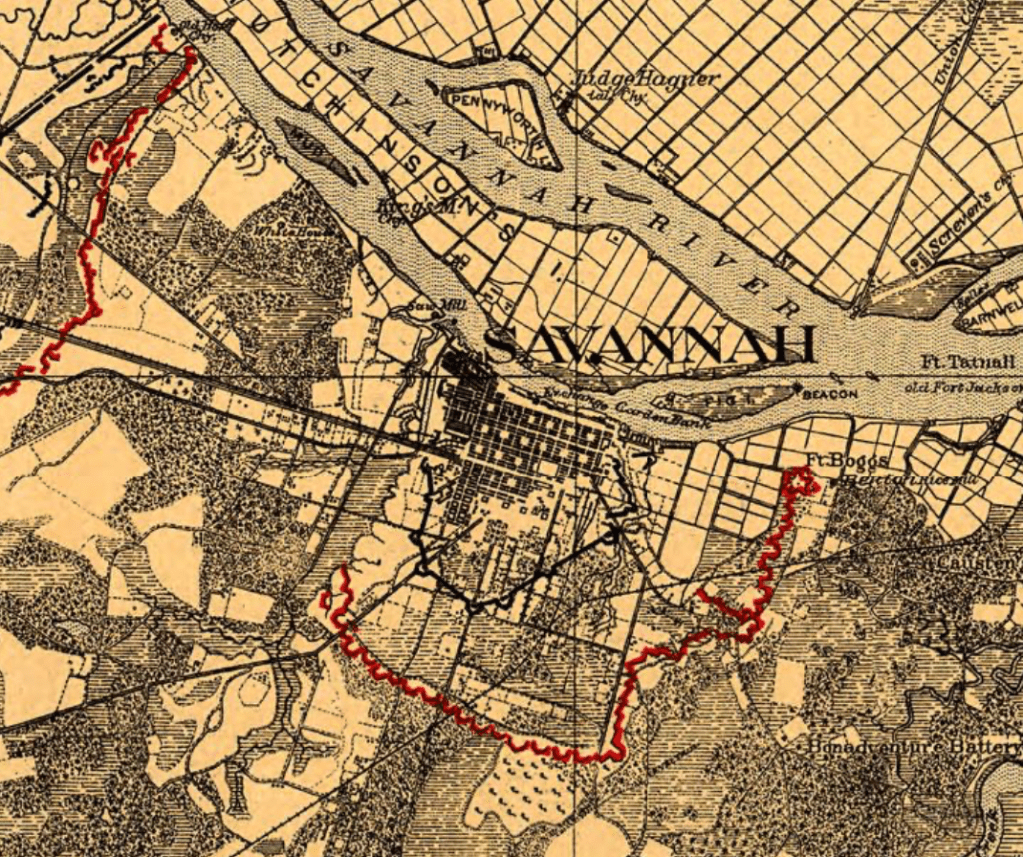

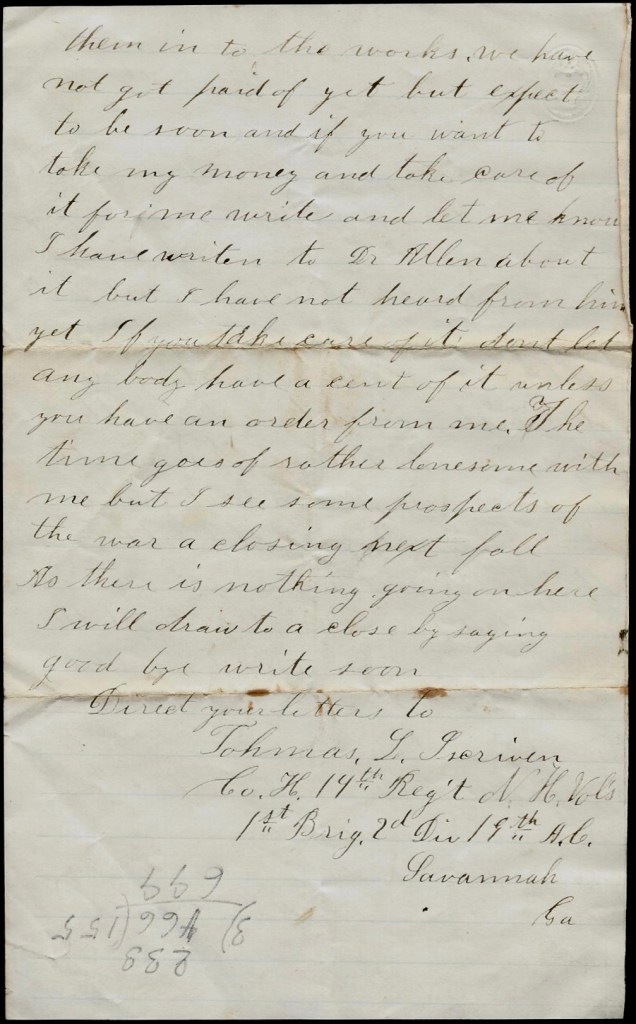

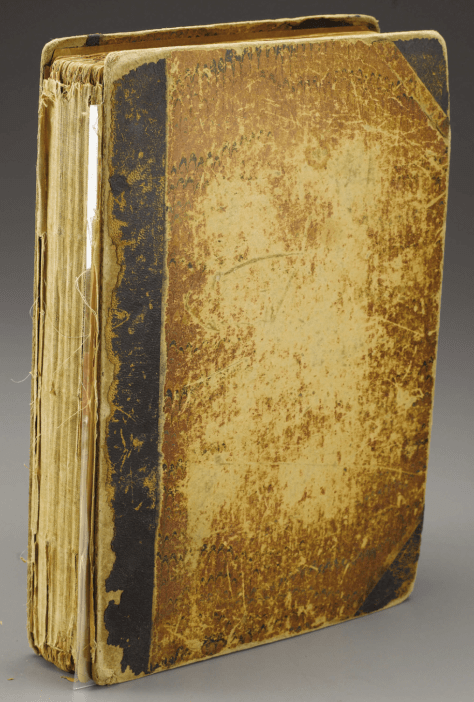

1 William Henry Thayer began his military career as a medical officer in the 14th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. He was appointed Medical Inspector in November, 1863, and served in that capacity until January, 1864. He earned the promotion to Surgeon-in-Chief in February, 1865. Thayer’s letters sold at auction in 2007 with dates from January 3, 1864 to March 10, 1865, written from various locations between Washington D.C. and Savannah, and ranging in length from one to 15 pages. They were pasted to the pages of the scrapbook in chronological order. The correspondence began in Concord, where Dr. Thayer wrote to his wife after being “…so fully occupied with my duties that I could not get through with my reports, & instructions for the medical officers…” One of the more interesting letters includes his account of meeting President and Mrs. Lincoln on a Saturday trip to the White House. Upon seeing the exhausted President, Thayer wrote that “…Mr. L was near the door, looking so haggard…” Later, Dr. Thayer related his experience after gaining a private audience with the President, and reiterates that Lincoln looked “very thin and hollow-eyed.”