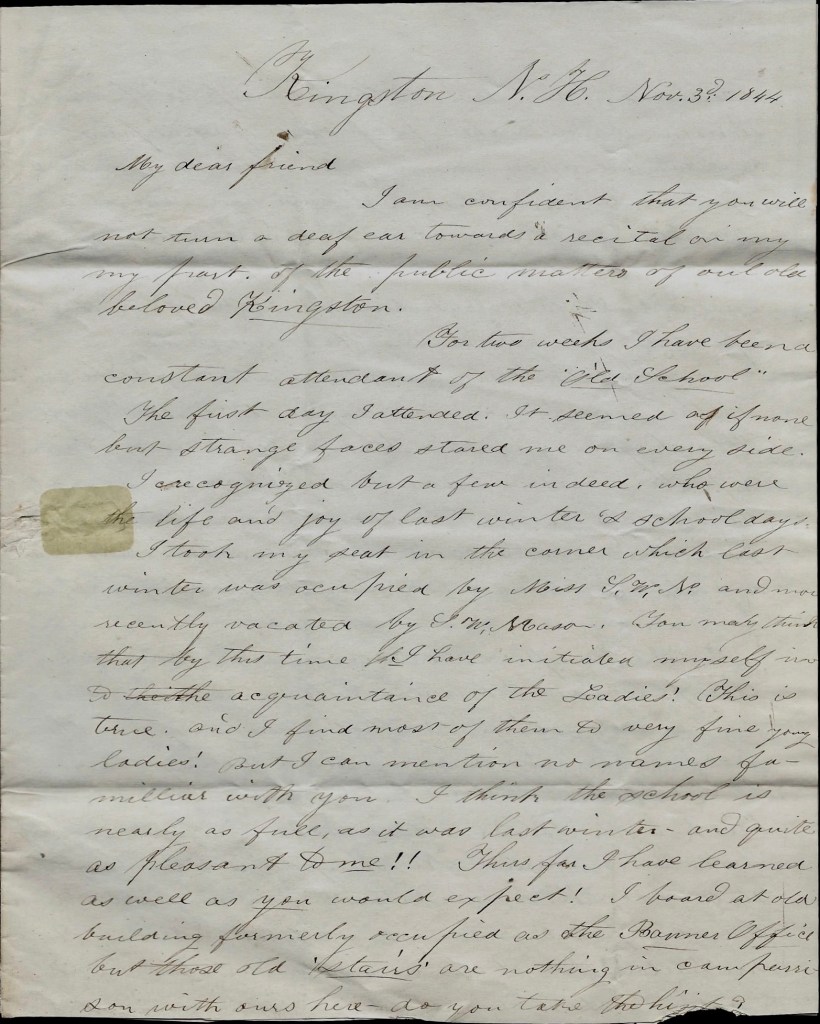

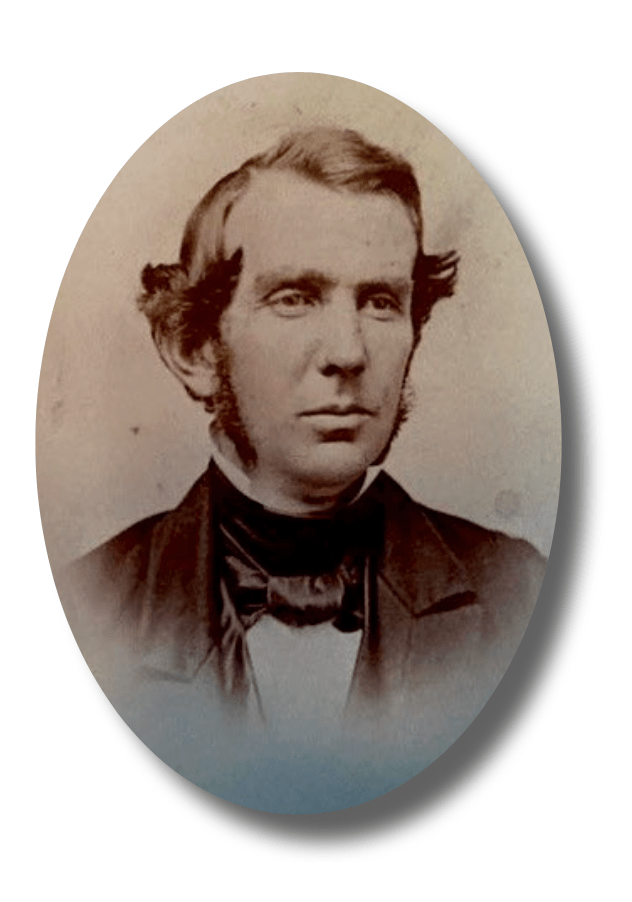

The following letter was written by Jeremiah Woolston Duncan (1810-1854), the son of John Duncan (1776-1852) and Elizabeth Woolston (1778-1851). He wrote the letter from New Orleans in February 1844 to his older brother, John A. Duncan (1806-1868) of Wilmington, Delaware.

Jeremiah was married in 1833 to Elizabeth Strode Brinton (1810-1859) and the couple had two children by the time of this 1844 letter. They would have at leasts four more children, the last two after the family moved to the fledgling city of Chicago in 1849.

“Jeremiah was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1810. He received, in common with all the other members of his father’s family, a good English education, but his active and enterprizing nature early asserted itself, and while still but a boy in years, he proceeded of his own volition to Philadelphia, where he became a clerk in a hardware store, remaining till he was twenty years of age. He then went into partnership, in Wilmington, with his brother, John A. Duncan, in the hardware business. In 1830 he withdrew from the firm and went into the lumber business with Baudy Simmons and Company, of Wilmington. He afterwards retired, also, from this firm and went into the West India trade and wholesale grocery business, in partnership with Matthew and Andrew Carnahan, in the same place. He next erected a steam saw mill on the “Old Ferry” property. In 1850 he removed to Chicago, where he engaged extensively in the lumber business. He owned large tracts of land in Michigan, near the straits of Mackinaw, and the town of Duncan, in that vicinity, was named in his honor. But the life he now led subjected him to frequent and severe exposures, and carried away by his activity and energy, he paid too little regard to his health. It thus happened that in the prime of his vigorous and most valuable life he contracted a fatal sickness. He returned to Wilmington and died, December 31, 1854. Mr. Duncan was a man highly respected in all his wide circle of acquaintance, and warmly regarded among his friends. His activity and energy were remarkable, and the results proportionate.” [Source: History of New Castle County, Delaware]

(Courtesy of Fred Diegel)

[Note: This letter is from the private collection of Richard Weiner and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

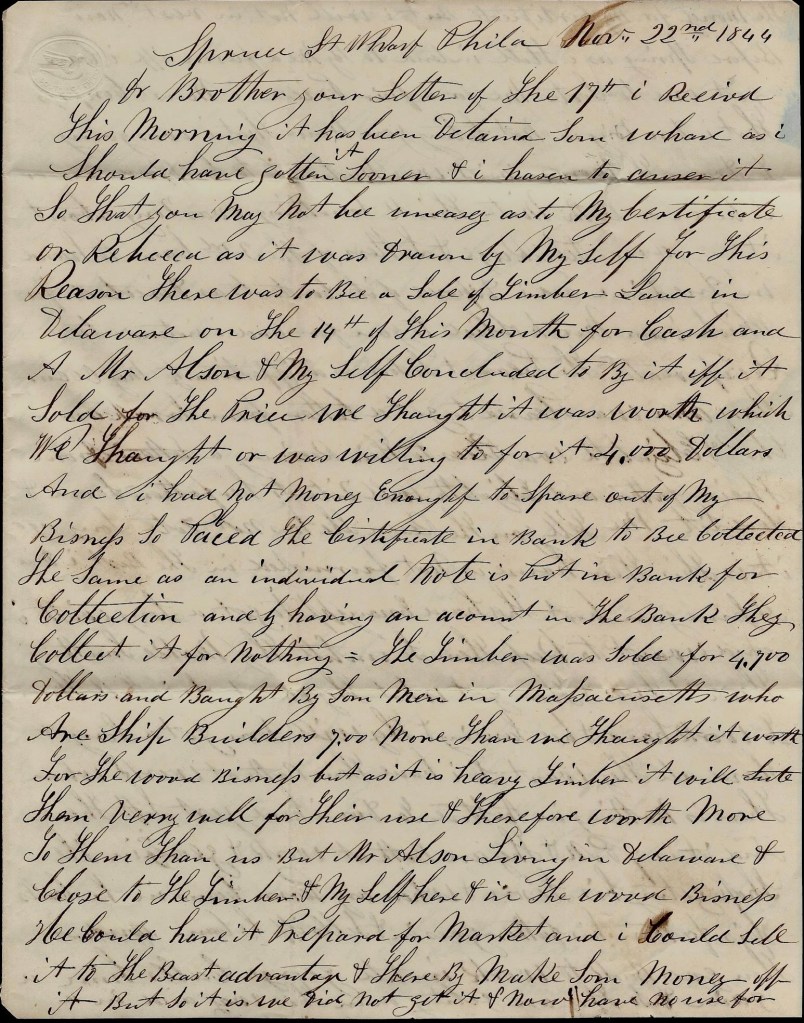

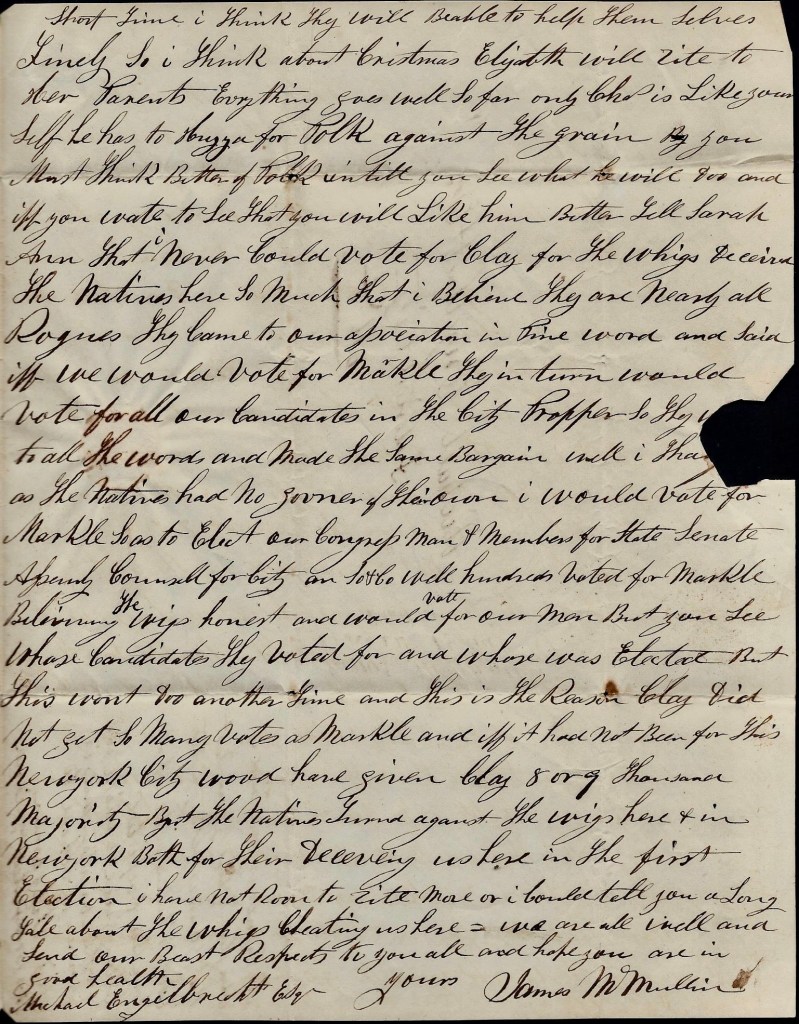

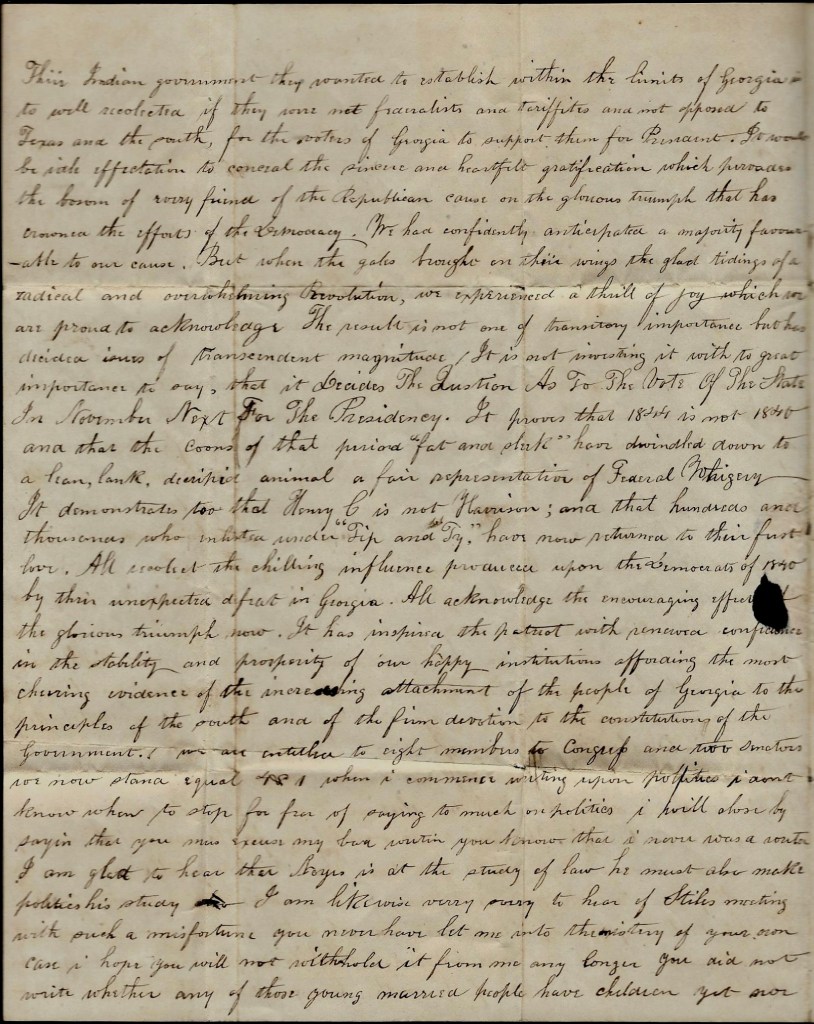

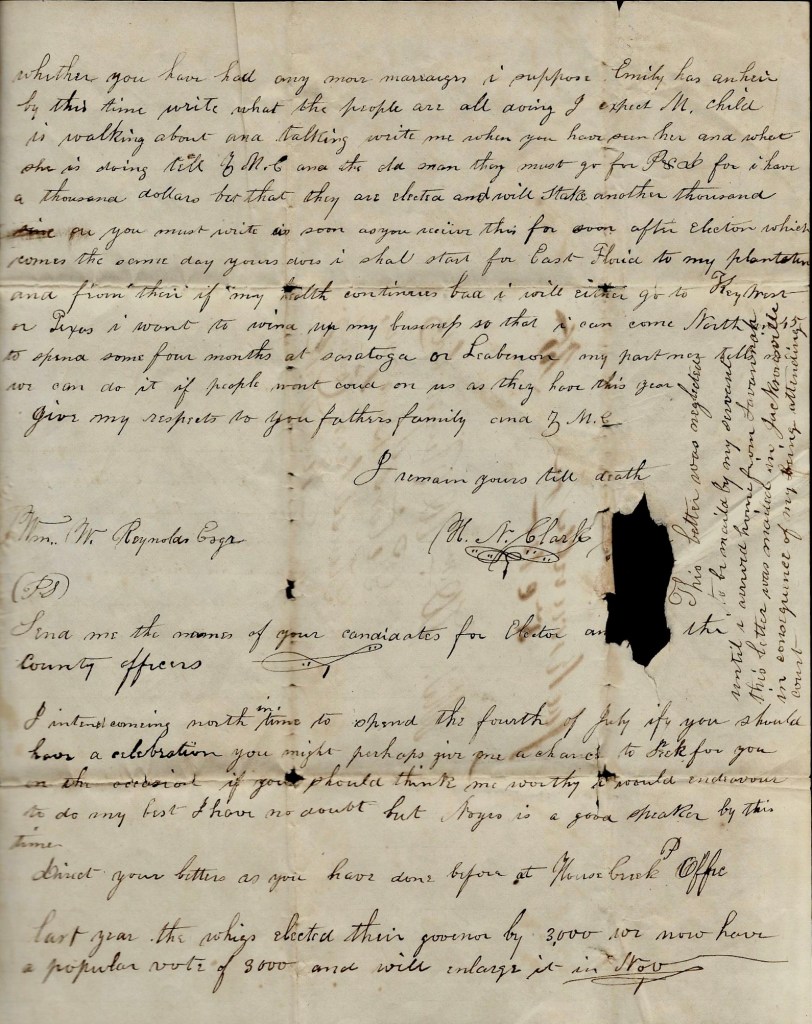

Transcription

St. Charles Exchange Hotel 1

New Orleans

February 22, 1844 2

Dear John,

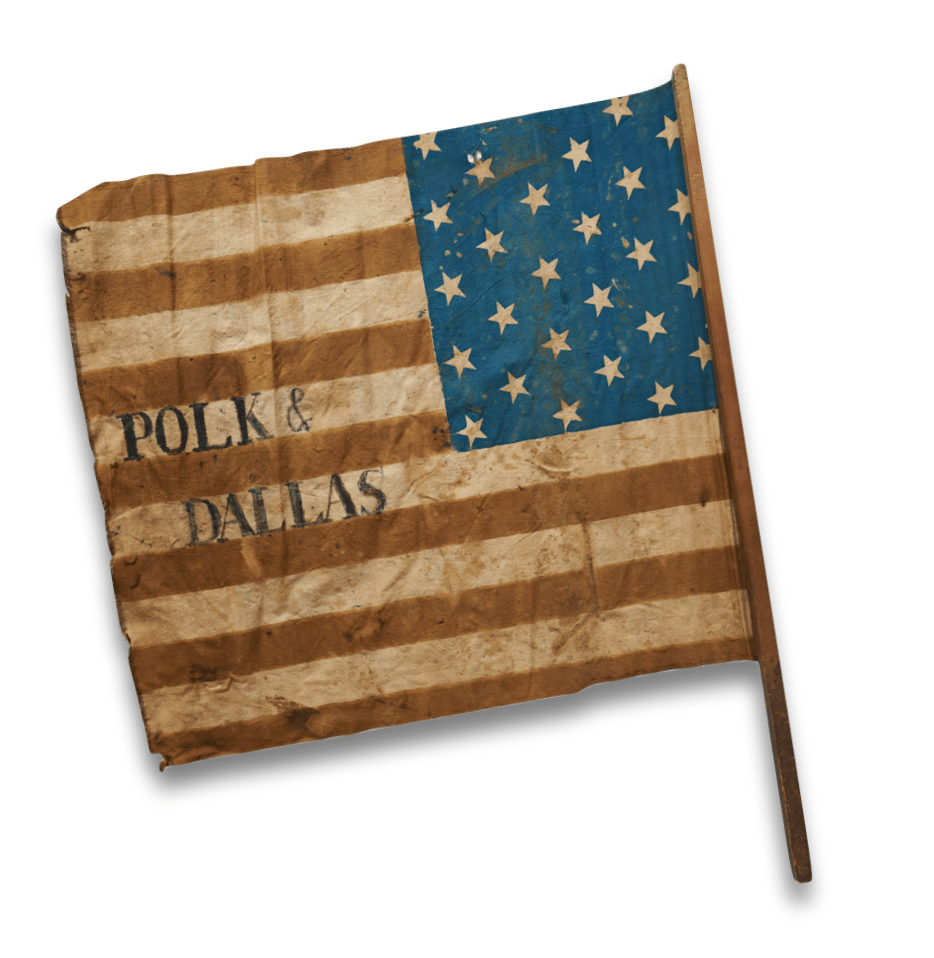

Having a little leisure before dinner, I thought I would improve it by writing you a few lines. Today here you will observe by a paper I mailed to you this morning, is a busy one. There is a great gathering of the Whigs of Louisiana beside a grand military parade, sham battle, &c. about going on at this moment—2 o’clock—and most of the business is stopped on account of it. Many stores closed.

Yesterday was another gala day being Mardigra [Mardi Gras 3] on which occasion carriage of men and women ride about the city in mask & all kinds of grotesque forms imaginable & form a procession the B[ ] throwing dust and flour in their faces at the corners (and by the way, you never saw a dusty city—it is here about ankle deep—and as far as flour, until yesterday we had a little rain which reversed the matter into mud half shoe deep). The citizens consider the turn on yesterday pretty near a total failure—nothing much but ordinary women & rowdies whereas heretofore respectable people used to parade. Old Harry stay much of his time at [illegible] & is to be here tomorrow & hold a sort of Levee in our spacious dining room. 4

This is the finest hotel I ever was in—much ahead of the Tremont or Astor House but, O Harry, how they plaster it on $3 per day or $15 per week if you stay a week at a time. This city is like all other cities—plenty of people here for the business at this time but the prospect for a lively spring trade is pretty good. The wharves look beautiful today. The immense number of ship with all their flags displayed—ships of many nations. It is really a pleasing sight. Steam boats by dozens a belching like volcanoes. I must say I really hate these high pressure boats. With all I had heard about the immense boats on the Mississippi, I am disappointed. The Empire on the North River would eat one of the largest for a breakfast. But there is a great quantity of them going & coming all the time and full of freight.

The Daily Picayune, 23 February 1844

February 24. I had to knock off for dinner. I have not found time sure to get at it again until this morning at 7 o’clock. If you ever saw a swarm of bees, this house has been one for three days past. I was at a great Whig gathering last night & they began to call for [Seargeant Smith] Prentiss of Mississippi who addressed the convention the day before & one continual cry for at least one hour.

I have ridden out round the city, down the Shell Road & Cr & taken a general survey. Went on the Parade [ground] after the Battle had been fought & see company after company of Frenchmen—all small men and all commanded in French—not a word in English. These French here are great military men. The 2nd Municipality, you could not be from New York in which most of the business is done & in the 1st and more in the 3rd. you will hear all the negroes talk French. I had not been down in the 3rd before the afternoon of the parade the whole of which I spent in that part of the town as it was a complete holiday.

The idea I had formed of the levee was a very enormous one. It to be sure is much higher than the rest of the city, but a stranger may land on it and walk into the city & not observe it. I could write you an hour more but must close. I have some other writing to be done this morning. Give my love to my dear wife & little ones & all your folks & to all my friends my best respects.

From your affectionate brother, — Jeremiah W. Duncan

P. S. Shall have much to talk [about] when I see you. T. H. Larkin is here. Old Mr. Handy of Chil & the 2 McMain Boys & sundry others.

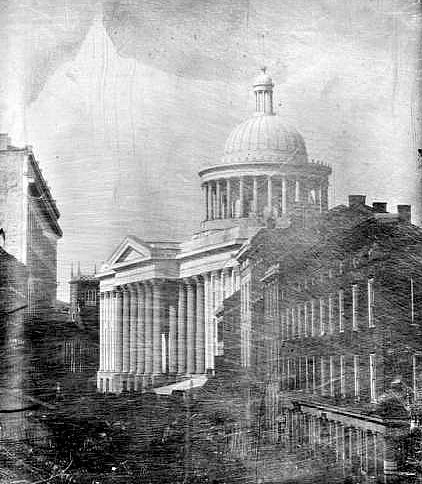

1 “The St. Charles was the first large building erected above Canal Street. Within its walls,

over the next hundred years, half the business of the city was to be transacted and half the

history of the state of Louisiana was to be written. The hotel was designed by noted architect James Gallier. It was the grandest hotel in the South, in fact, the first of all great American

hotels. Oakey Hall, who later became the mayor of New York, said of it, ‘Set the St. Charles

down in St. Petersburg, and you would think it a palace; in Boston, you would christen it a

college; in London, it would remind you of an exchange; in New Orleans, it is all three.’ Mr.

Hall was unable to contain his surprise at finding in the city of New Orleans something far

grander than anything New York could boast of. The hotel had a magical effect upon the quarter of the city in which it stood. It rapidly built up the First District, known as the American sector. Around it, as a center, gathered the traffic and trade of the city. Churches sprang up near it; stores and dwellings spread out in every direction. St. Charles Street, which did not extend far above the hotel, became the most animated thoroughfare in the United States.”

2 Jeremiah’s visit to New Orleans in February 1844 was just prior to a fire in the summer of 1844 which destroyed about seven blocks of buildings between Common and Canal Streets, near the Charity Hospital.

3 After decades of suppression (under Spanish rule) the Mardi Gras parade was reinstated in New Orleans in 1837 (at least the first recorded). It remained popular until the early 1850s when it began to wane, but then was reinvigorated in 1857.

4 “Old Harry” is often an alternative name for the Devil but in this case it is referring to Henry Clay, the Senator from Kentucky, who was being nominated again by the Whig Party as their choice for President in 1844.