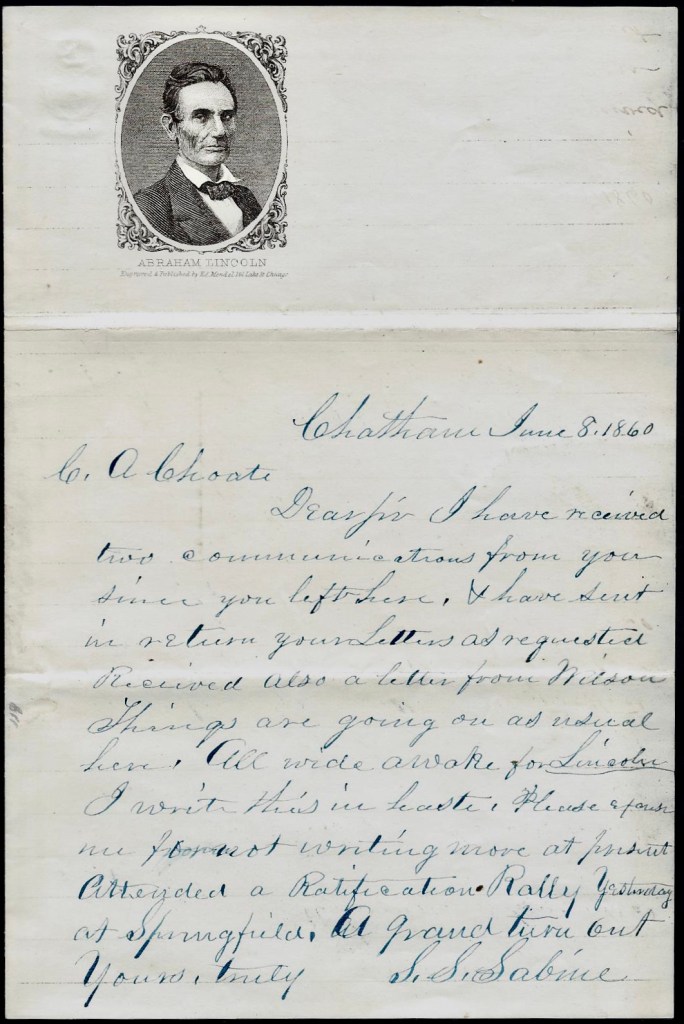

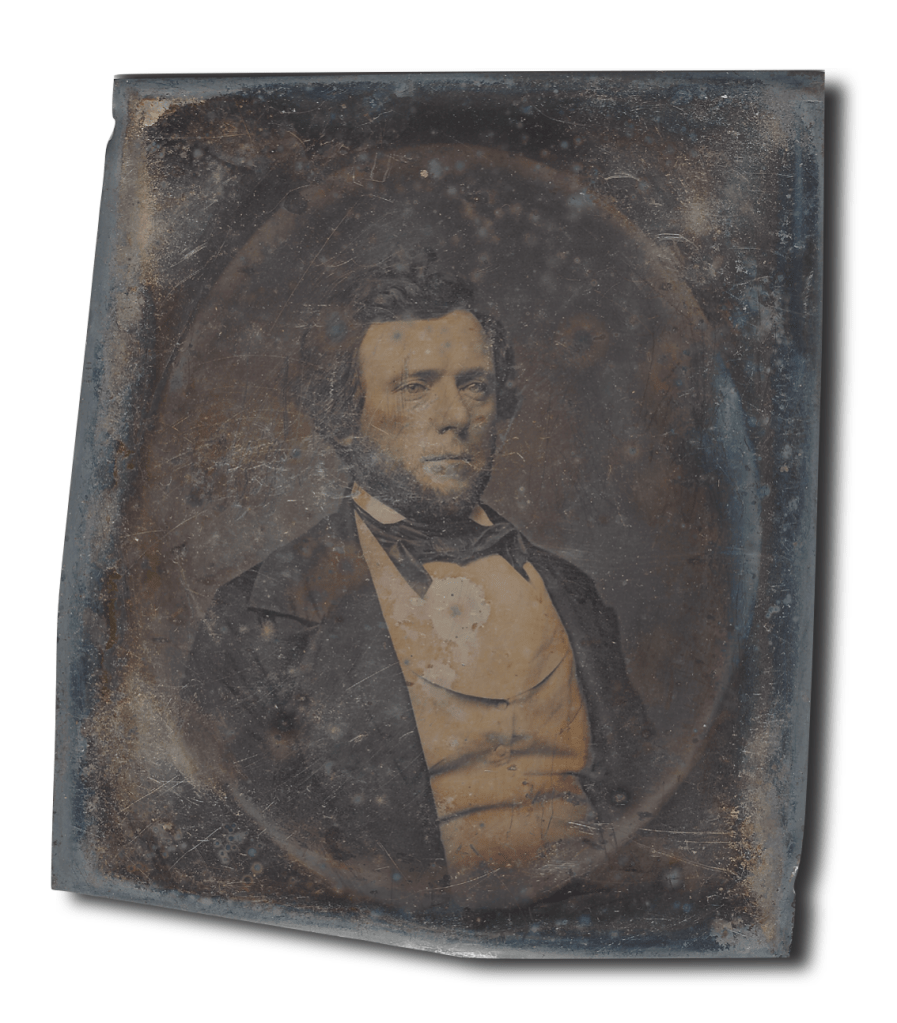

The following letter was penned by Levi Bird Duff (1837-1916), the son of Samuel Duff (1807-1890) and Catherine Eckelberger (1810-1880) of Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. Raised in the Saltsburg area, after graduating from Allegheny College, Levi moved to Pittsburgh to study and practice law upon his admittance to the Allegheny Bar Association in April 1860. One year later and just weeks after the start of the Civil War, Duff enlisted in Co. A, Ninth Regiment, Pennsylvania Reserve Corps. His acumen as a soldier and leader led to his rapid rise through the ranks, from corporal to captain to major to lieutenant-colonel. Duff led his troops in over twenty battles during his enlistment, such as Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. During his military career, he survived bullet wounds through the right lung and right thigh, though when the latter led to the amputation of his leg in 1864, he received an honorable discharge.

Duff returned to Pittsburgh to continue his law practice and start a family with his wife Harriet (Nixon) Duff, whom he married during the war and whom he exchanged dozens of letters during those years. He allegedly would send Harriet flowers or leaves from the battlefields he traveled to along with the letters. Duff displayed a strong passion for politics and inciting change, especially in regards to slavery and racial subjugation. He maintained the same political platforms throughout his law career, including his three-year term as district attorney of Allegheny County until 1868. Duff had two children with Harriet prior to her death in 1877. He remarried Agnes F. Kaufman in 1882. After Agnes’ death in 1913, he decided to close his law practice and move to Lansing, Michigan to spend his final years with his son Hezekiah’s family until his death in 1916. His legacy lives on through his letters recounting his war triumphs and tribulations, which 150 years later are now preserved and available to view at his alma mater Allegheny College.” [Source: Union Dale Cemetery]

Duff’s Civil War letters were edited by Jonathan E. Helmreich in 2009 and published under the title: To Petersburg with the Army of the Potomac, the Civil War Letters of Levi Bird Duff, 105th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

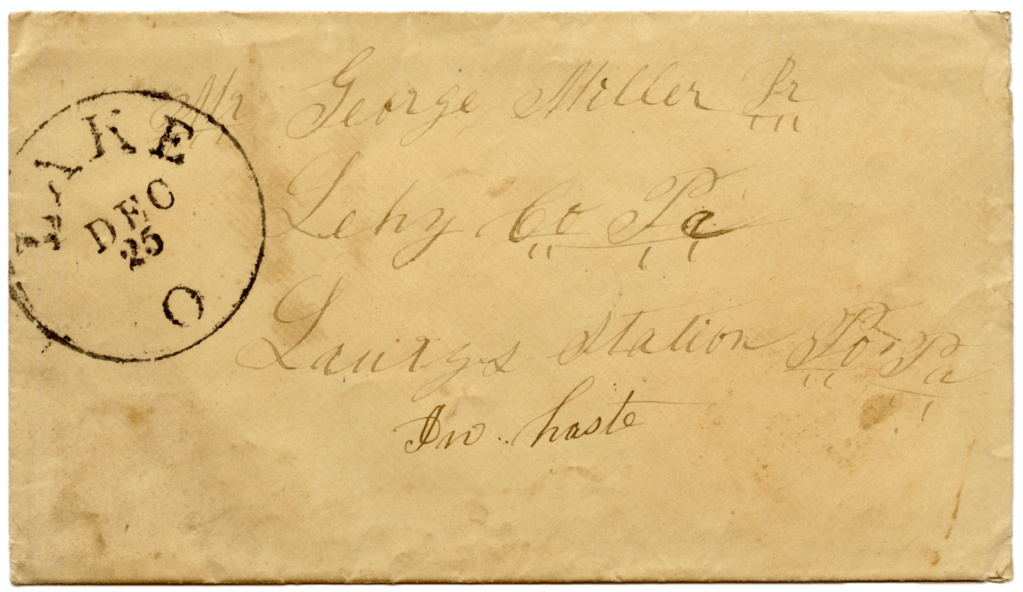

The letter was sent to his younger brother, Sardis Tunis Duff (1840-1930) who had apparently gone to Texas but not before being enumerated in his father’s household in Clarion, Pennsylvania, where his father was a merchant in the borough. When he registered for the draft in 1863, he was identified as a “student” in Indiana county, Pennsylvania.

Transcription

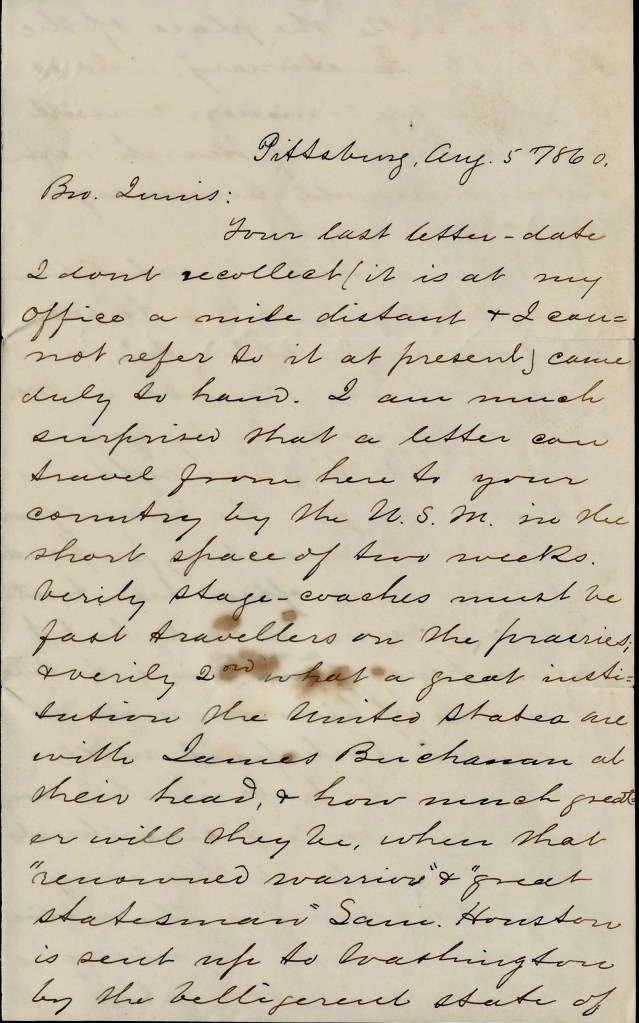

Pittsburg[h], Pennsylvania

August 5, 1860

Bro. Tunis,

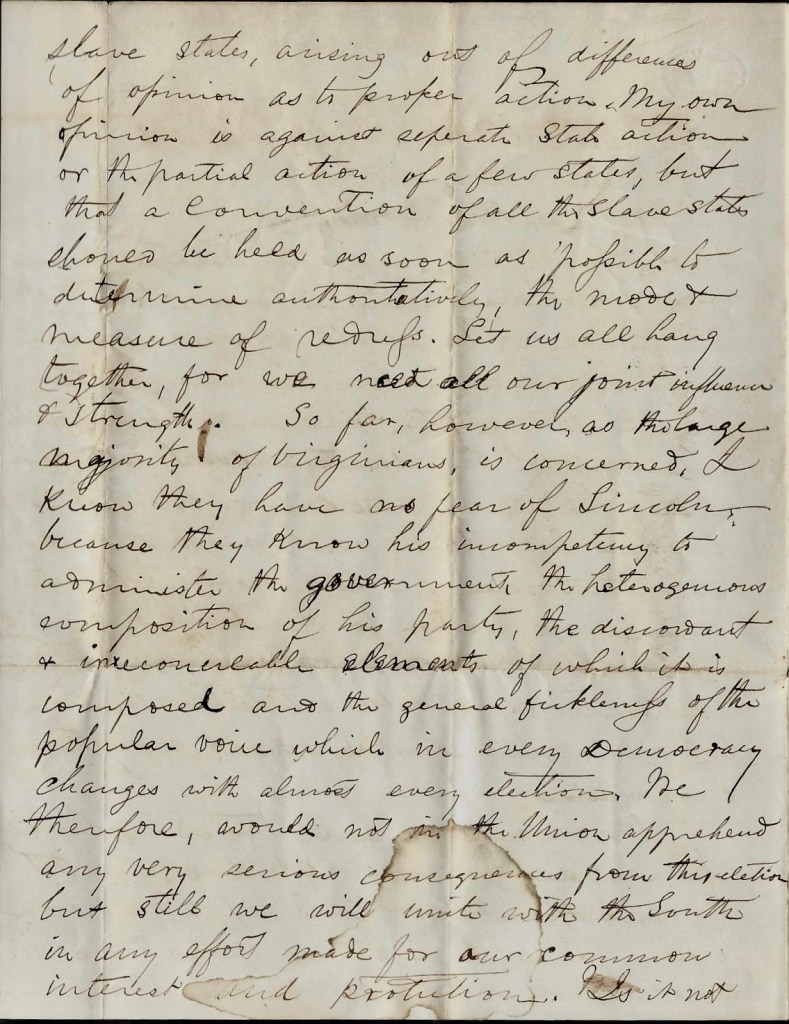

Your last letter—date I don’t recollect (is at my office a mile distant & I cannot refer to it at present) came dult to hand. I am much surprised that a letter can travel from here to your country by the U. S. mail in the short space of two weeks. Verily stage coaches must be fast travelers on the prairies & verily, 2nd, what a great institution the United States are with James Buchanan at their head, & how much greater will then be when that “renowned warrior” & “great statesman” Sam Houston is sent up to Washington by the belligerent State of Texas to take the place of the “Old Public Functionary,” who is to retire by common consent on the Fourth of March next. Indeed then will Cumming’s time have come.

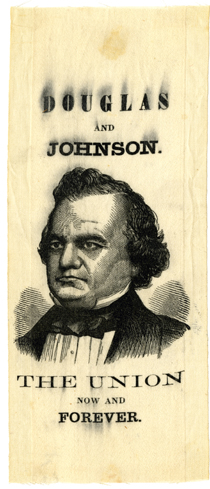

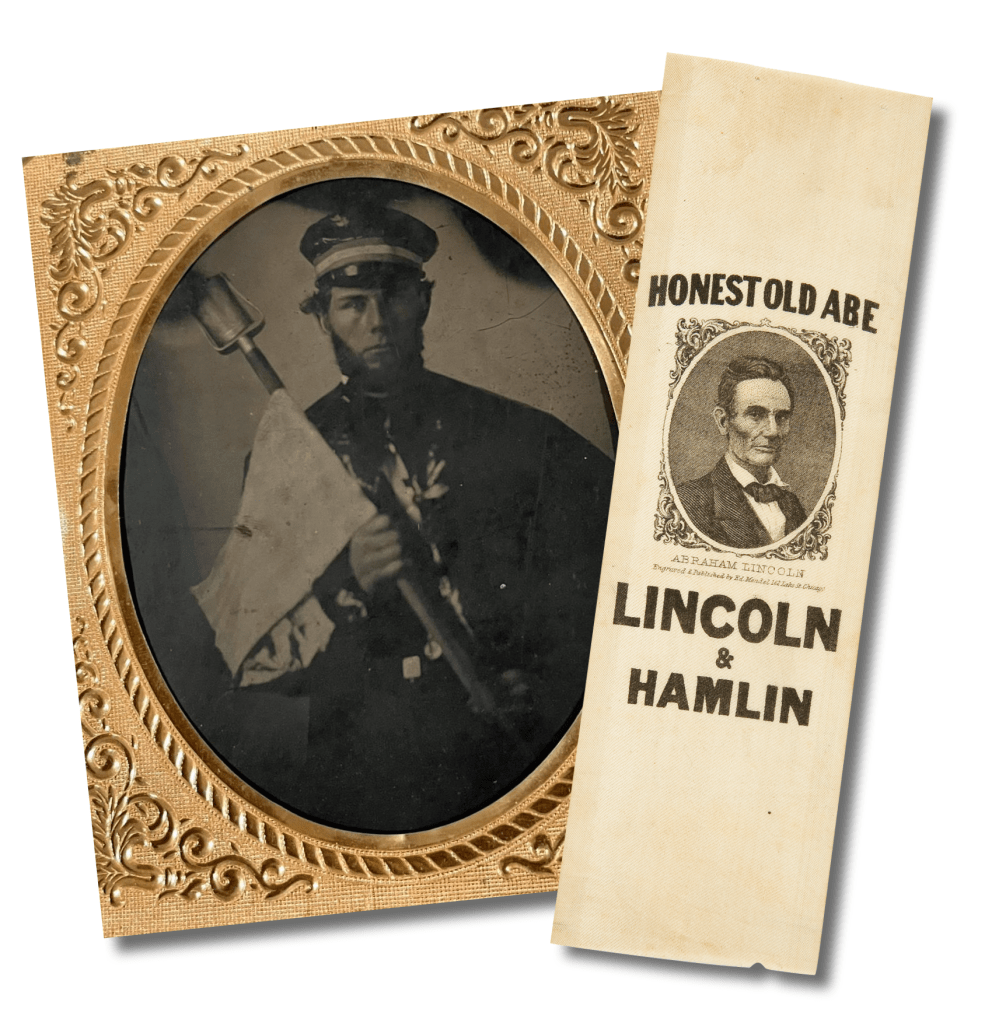

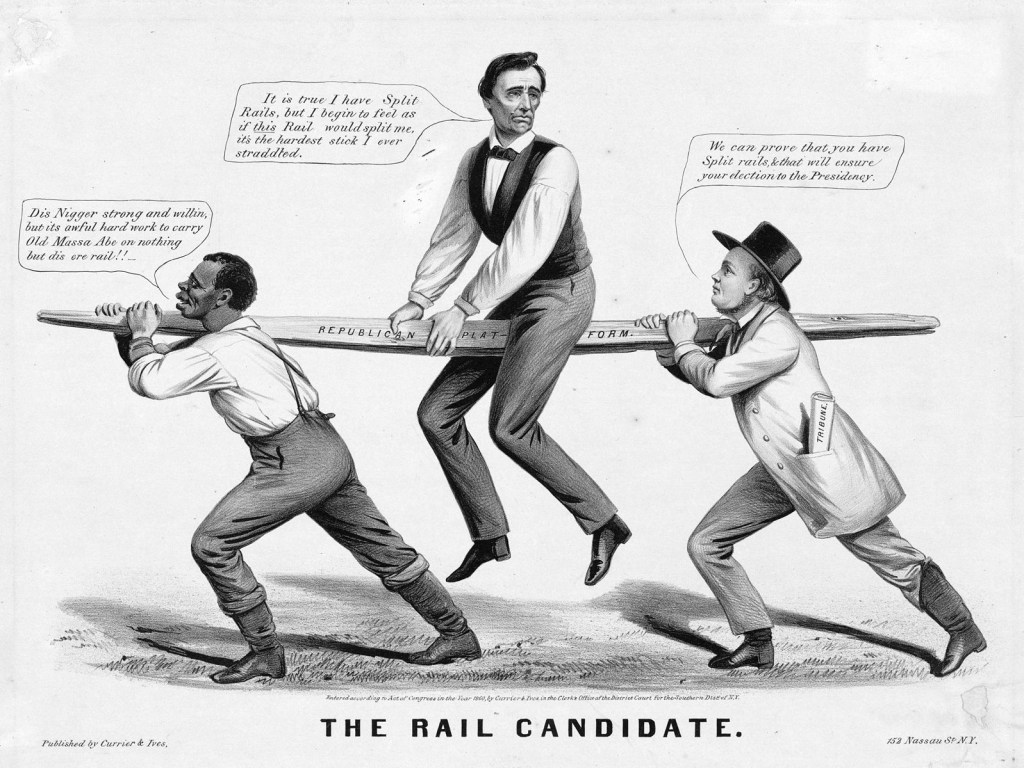

Hereabouts the abolition Rail-splitters threaten to ride Lincoln to Washington on a rail which he made in Macon county, Illinois, thirty years ago. 1 Won’t this be a righteous retribution for the indulgence of his rail-mauling propensity! Men have often been treated to a ride on a rail but I never heard of a man being tortured by one of his own manufacture. Perhaps it will not come to pass in this case; but they make fierce threats & low boasts up this way of making Lincoln the victim of his own rail. The riding is to take place in November next. We want our Southern brethren to come up & aid us to ride this man Lincoln on his own rail, but they demur & say it shan’t be done; & that if, contrary to their orders, it should be done, they will dissolve the Union. Herein we think our Southern brethren are a little inconsistent. For should the same Lincoln be foolish enough to visit his native place down in Hardin county, Kentucky, how the inhabitants “round about” would long for an Illinois rail to give him a ride. Yet they won’t come up here & help us to do it. They want to do all the rail-riding themselves. We wish to partake of the fun & they object. Our fellows, notwithstanding these protests, are making the “necessary preparation” for the ride & I have no doubt it will take place next November as I before said.

But I must drop this subject for the present to ask you how Texas is getting along. Wonderful reports have reached us that the Abolitionist are burning up the State & doing many other things. I cannot recollect them all just now. How is this? Give me some information respecting these things if you can.

I see by the reports from your country & also by your letter that the weather has been very warm there this summer. This warmth may convince you that the climate is not so pleasant as you anticipated. You are, I think, a little too far south.

Let me know how the political fight goes on down there. It is now said that Sam Houston is declining & that his state will go for Breckinridge.

Your friend & bro. — Levi Bird Duff

1 The Chicago History Museum informs us that Abraham Lincoln acquired the sobriquet “The Railsplitter” in May 1860 when Illinois Republicans convened at Decatur to endorse a favorite son for president. “Lincoln was the likely choice but his supporters felt he needed a catchier nickname than ‘Old Abe’ or ‘Honest Abe.’ Thus, Richard J. Oglesby and John Hanks, a first cousin of Lincoln’s mother, located a split-rail fence supposedly built by Lincoln in 1830. When they walked into the hall carrying two of the rails—decorated with flags, streamers, and a sign that read, ‘Abraham Lincoln/The Rail Candidate’—the crowd went wild.”