The following memoirs were recorded in 1893 by James Woodell Kenney (1835-1900), the son of Michael Kenney and Jane Woodell (d. 1844) of Arlington, Middlesex county, Massachusetts. Kenney’s memoirs and his military records inform us that he mustered into the 1st Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery in August 1861, commanded by Josiah Porter. He was wounded in May 1864 during the Wilderness Campaign and mustered out of the battery on 29 August 1864 after three years service. He was married to Lizzie S. Shattuck on 24 December 1868. In 1870, James and Lizzie were enumerated in Charleston, Mass., where he was employed as a clerk in a printing office. Vital records of Massachusetts inform us that he died of a cerebral hemorrhage on 6 April 1900 in Boston.

James’ brother, Andrew J. Kenney (1834-1862) is mentioned several times in the memoirs. He mustered into Co, B. 40th New York Infantry and was killed in action during the Battle of Williamsburg on 5 May 1862. According to Mass. vital records, he was married on 25 November 1860 to Mary Jane Hodge (maiden name Woodell) in Ashburnham, Massachusetts.

The memoirs were addressed to James’ nephew and namesake, James W. Kenney. Family tree records are scanty but my hunch is that this nephew was James W. Kenney (b. 1858), the son of Michael Kenney (b. 1831) and Mary McKenna Sheehan (1828-1882). Michael was a rope maker and later a shoe factory worker in Roxbury, Massachusetts and during the Civil War he served as a private in Co. K, 1st Massachusetts Infantry.

[Note: These memoirs were provided to me for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by Tom Clemens. I could not find them transcribed elsewhere on the internet or in book form though the original might be housed at the U. S. Army Heritage & Education Center at Carlisle Barracks, Pa., as they claim to have a folder marked, “Memoirs of James W. Kenney’s Service.”]

Transcription

Dear Nephew and Namesake,

I greet you in love and kindness. Thinking you might like a short sketch of your Uncle Jim for whom you were named, and as I may have passed beyond “the River” before you grow old enough to remember me, or read these lines. the most of the sketch will be about my military service in the War 1861-5 which I thought might interest you. I kept a journal while in the service of every day—the drills, marches, reviews, battles, &c. After keeping it over two years, and being afraid I might lose it, I sent it home by a comrade going home on a furlough and he lost it, so the journal was gone up. What I write you in this will be taken from letters I wrote home and other memorandums. By reading this you will see what battles I was in any by referring to the History of the War, you can obtain an account of those battles. I was in the Army of the Potomac and served under every General that commanded it from General McClellan to General Grant.

I will commence with my birth, town, name (that is, the J. W. part) and follow with the army life. So many years have passed since that took place I cannot remember many things I would like. — Uncle Jim. January 1893

I was born in the town of West Cambridge, Mass., now called Arlington (name being changed about 1867) on September 26, 1835. I was named James Woodell for my grandfather (Woodell being my mother’s name before marriage). I also had an uncle J. W. who served in a Mass. Regoment and was killed in the Southwestern Army and also other relations who served in the Army or Navy in the war.

The town is between Lexington and Cambridge…The British troops crossed the river and landed in Cambridge, passing through West Cambridge on their way to Lexington and Concord. On the night of April 18th 1775 about midnight. the next morning the Battle of Lexington and Concord was fought and as the “Yankees” were coming in from the other towns making it rather warm for the British, they commenced to fall back to Boston. They were under fire almost all the way and lost many men on their return. There were more British and Americans killed in West Cambridge than at Lexington, and to West Cambridge belongs the honor at making the first capture of stores, provisions, and prisoners in the American Revolution on that day in the center of the town.

Cambridge is the place where General Washington took command of the American Army, its headquarters being there at the time. The old Elm tree under which he stood is still standing. Also the house in which he had his headquarters, bing for years the home of Longfellow—the poet. Here is also Harvard College, founded before that time….I was born on historical ground and grew up with a strong love for my country. My father had also held a commission as ensign in the 1st Regiment Mass. Militia under Gov. Lincoln in 1832.

I will not enter into details of my early life but will say my Mother died when I was quite [page missing]

…as the lawyer had to go out of town to court, he could not attend to the details. I offered my services in any way and it was left in my hands to call a meeting that evening at his office or the Town Hall. I went out and found the others, then got three uniforms—two that had belonged to father, and one that belonged to me as I had been in the militia before father died but gave it up then. Then got a fife and drum to make a noise and went all over town telling every one of the meeting in the Town Hall that evening. The Hall was not large enough to hold the crowd that came—the largest gathering ever held in town. We soon raised a company, the lawyer was chosen Captain and I was chosen First Lieutenant. As the Captain had so much to attend to in court fixing up his cases and turning them over to other lawyers. I had all the charge of the company in drill and I often duties in the daytime. We drilled in forenoon and afternoon on the street in marching and company movements and in the Hall in the manual of arms in the evening. My older brother Andrew came home and enlisted in my company. So we all three were in the service.

We continued drilling until the last of May when we were told of a regiment being raised in Brooklyn, New York, by Henry Ward Beecher that they had seven companies and wanted three more to fill the regiment and start at once for the Seat of War. My company and two others from Mass. took special train for New York on the evening of May 30th, arriving the next morning, and after breakfast, went over to Brooklyn and took quarters in a five story armory large enough for two companies on a floor. In the afternoon I went over to New York and took boat for Governor’s Island to see your father. I found him in “Castle William,” the round fort on the point of the island. He was surprised to see me. On Sunday we all went to hear Beecher preach in the morning and in the afternoon a few of us went to the Catholic Cathedral to hear the singing. It was fine.

We found out that there were not 7 companies—that all there were was about 150 men—the toughest looking you could find and they were not drilled or uniformed. The food they gave us was so bad we could not eat it and we could get no satisfaction from those raising the regiment so we called a meeting of the officers of our three companies and voted to return to Massachusetts. (You will understand we were Mass. troops and not mustered into U. S. service.)

On the evening of June 4th, took boat from New York to Boston, arriving the next morning. After breakfast, the officers went to the State House to see the Quartermaster General of the State and have him put us in camp until he could send us away but at that time the State did not have camps for troops as they did later on. But we were granted leave to go to Fort Warren (Boston Harbor) until we could make arrangements for something else. the companies went down in charge of their 1st Lieutenants and the Captains remained in town to see what they could do. They came down to the fort on June 8th and we went up to the City and were dismissed until the 11th when we all reported and started again for New York, arriving the next morning and taking boat up the river for Yonkers. On the morning of the 13th two of the companies were mustered into the U. S. Service. As each company was a few short, we lent them a few men to be exchanged back into our company later on. My brother Andrew went into one of those companies [Co. B, 40th New York Infantry] and remained in it until he was killed at Williamsburg, Virginia.

As we were going to New York Regiments, we would have to get N. Y. State commissions. The two companies mustered in were mustered as they were, officers and men, but my captain wanted a new election which was held and the same officers reelected although te captain tried to make a change and throw me and another out, and put in two friends used to drink and bum around with him. I heard what was going on and we had a row. He got some plain remarks from me and it ended in my taking all the men but about 12 and marching them out and took cars for New York City. I had two offers while there to take my men, fill up my company, and go as captain in some New York Regiment but I had enough of New York and was going home. I got quarters for my men that night in the Park Barracks near City Hall and started for home the next evening and arrived all right. The citizens were provoked at the action of the captain in breaking up such a fine company. I was offered all the backing with money wanted to raise another company but I was anxious to get away and did not want to wait so long as to raise and drill another company. A captain belonging to the 16th Mass. Regiment Infantry wanted me to take my men and join his company but as I could not get any satisfaction as regarding my being an officer in his company (and the men wanted me as an officer over them), I would not go. So you see I had bad luck all around in getting away. One reason was Mass. was so patriotic. We had about three times as many companies enlisted in the State as was called for.

I remained around home working or attending to some military duties until August 27th when being in Boston I found out the Boston Light Artillery had returned from its three-months service and was reorganizing for three years. I dropped my commission and enlisted in the Battery and was mustered into the U. S. Service for three years on the 28th of August. We went into camp in Cambridge about half a mile from the Arlington line.

Arriving in camp we were formed into Gun Detachments and the Warrant Officers appointed. I was made Gunner with the rank of corporal and took charge of a Gun Detachment. I soon picked up the drill (as artillery was new to me) and soon had the best drilled squad on Sabre and Gun Drill. I was promoted to Sergeant afterward and remained as such during the rest of my service.

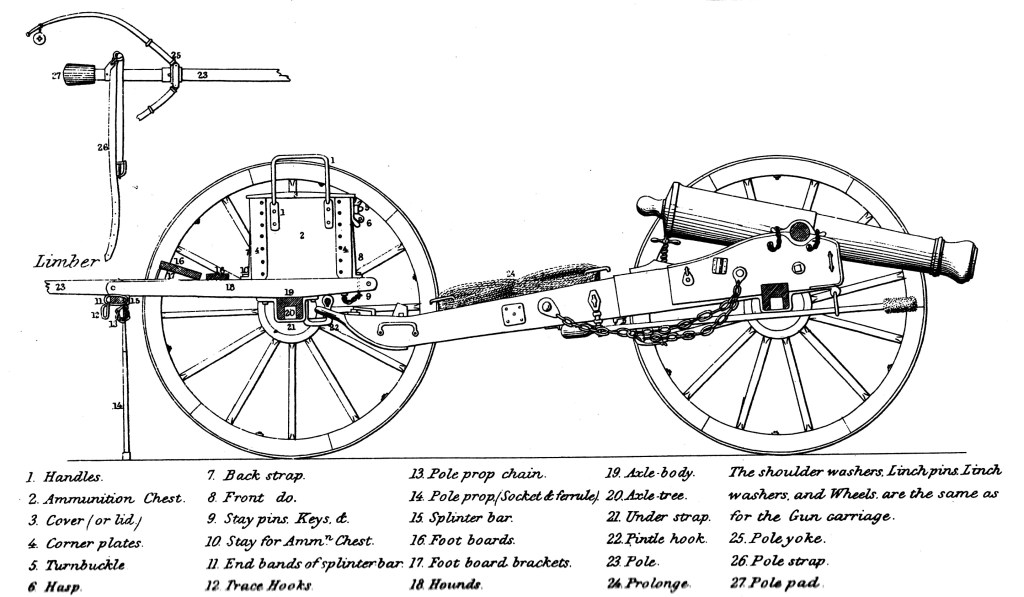

Perhaps now would be a good time to give you an account of the organization of a Battery and the duties of the men. This will be on a war footing as all troops are about one-third less in time of peace. Artillery is generally formed for field service, one third short range (smooth bore) 12 lb. Howitzers or Light 12’s called Napoleons, and two-thirds long range, or rifle, generally 10 lb. [ ], although our army had about the same number of each at the last of the war owing to the nature of the ground fought over being woody. Most of the fighting was at short range. There are 14 carriages in a Battery, 6 gun carriages with a gun mounted on the hind wheels, and an ammunition chest on the front wheels. The trail of the gun hooks on the axle of the front wheels when on the move, but rests on the ground when in action. Six caissons which carry ammunition, two chests on the hind wheels, and one on the front wheels, the front and rear parts of the caisson couple together the same as the gun carriage and are alike and can be exchanged when wanted, Thus in action the caissons are left in a sheltered place when convenient and if the ammunition of the gun limber is running low, the limber of the caissons come up and take its place and the gun limber returns to the caisson and refills from the rear chests, ready to exchange again. There is an extra wheel on the rear of the caisson, an extra pole under the carriage, shovel, axe, pick, water buckets, &c. One carriage called Battery Wagon with half round top to carry extra feed bags, parts of harness, halters, saddlers tools, wheelwrights tools, and various stores. One carriage called Forge or traveling Blacksmith Shop for shoeing horses and doing iron work of all kinds.

We have about 140 horses, three pair to each carriage, one for each sergeant, bugler, and artificer, and the rest are extra or spare horses to replace those broken down or lost in action. There are 150 men in a full battery, 5 commissioned officers (1 captain and four lieutenants), 8 sergeants, 12 corporals, 2 buglers, and three artificers. The Battery is divided into sections, two guns and two caissons make a section. Also into Gun Detachments, one to each gun and caisson.

Now I will give you a list of their duties. The captain is in command of all, one lieutenant in command of each section (taking 3) and the rest of the junior 2d in command of the caissons when they are away or separate from the guns. One first sergeant who is over he company next to the lieutenants and receives orders (in camp) to pass down to the other sergeants for details &c. draws rations, clothing &c. One quartermaster sergeant who draws forage or grain for the horses and looks after the baggage wagons. Six other sergeants, one for each gun and caisson, they having charge of the two carriages, horses and men. Twelve corporals, one for each gun and caisson and called 1st and 2nd Corporal (A Gunner and No. 8 man). They are under the sergeants. Buglers who blow camp and drill calls. Three artificers (one blacksmith, one wheelwright, 1 harness maker) to attend to all the work in their line. There is a driver to each pair of horses and he rides the nigh one when on duty. They take care of their horses—cleaning, feeding, and driving. Also take turns standing guard over the horses at night. Others are detailed to clean the extra ones and one man takes care of each sergeant’s horse as he has to look after the others while cleaning and feeding.

I will now give you the duties of the gun squad with the gun unlimbered and in position, the limber in rear of the gun, horses facing the rear of the gun, the drivers dismounted and “standing to horse” holding them by the bridle. The pole driver holds the sergeant’s horse when firing, he being dismounted and in charge of the gun. Standing in the rear, 8 men and the Gunner is a gun squad. the Gunner goves the order to load, cut the fuse, fire &c., he receiving the order from the sergeant, also sights the gun. The men are numbered from 1 to 8. No. 1 is on the right of the muzzle and sponges and rams the gun. No. 2 opposite him and he inserts the cartridge and shot or shell, having one in each hand. No. 3 on the right, he thumbs the vent, then steps to hand spike in end of te trail and moves the gun to right or left for the Gunner, then pricks the cartridge and steps to place. No. 4 is on the left and he fixes a friction primer to the lanyard, inserts it in the vent, stepping back to place, ready to pull at the order to “Fire.” No. 5 is on the left and half way between No. 2 and the limber. He takes the ammunition from his position to No. 2. No. 7 stands on the left of limber and takes it to No. 5. No. 6 stands at the rear of ammunition chest, cuts the fuze and delivers it as ordered to No. 7. No. 8 is the 2nd Corporal of the Gun Squad and in charge of the caisson and remains with it and attends to any order received. If to pack any ammunition from rear chests to limber, he would dismount his drivers and set them to work. The men are drilled at all the duties on guns and horses. Also drilled to work short-handed, one man doing the duty of two, three or more. On drill the sergeant would say, No. so and so knocked out, and sometimes would knock out almost all the squad and then en would go right along with the drill so when it came to active work, the men knew just what to do.

We remained in camp at Cambridge drilling on the guns and in field movements from August 28th until October 3rd. I went home quite often while there as the horse crew passed the camp and our officers let me go out of camp when not required for duty in camp or drill, and then men did not abuse the privilege. On October 3rd we started by railroad for Washington, passing through New York, Philadelphia, & Baltimore, arriving all right and going in camp on Capitol Hill in rear of the capitol.It was quite a different place then from what it is now. The capitol was not finished and on the Hill were log houses with negroes, pigs, and geese around loose (we caught some). The streets were awful from the gun carriages, wagon trains, &c. The mud at times was up to the hubs of the wheels and horses up to the belly.

When we left home we had two six-pound smooth bore guns, two six-pound rifled guns, [and] two twelve-pound Howitzers. While here we received orders to turn in the four six-pound pieces and take four 10-pound Parrott Guns, rifled—a fine gun and extreme range—about 5 miles.

There was a review of 75 horse companies and 22 batteries by General Scott, the President, Members of Congress, and others. We were picked out and received orders to join Gen. Franklin’s Division across the river. On the 14th October, we crossed Long Bridge and went in camp near Fairfax Seminary about three miles from Alexandria. Our camp was named Camp Revere in honor of a friend of the captain—Major Revere of the 20th Massachusetts Infantry. Our division has twelve regiments of infantry, 1 regiment of cavalry, and 4 batteries.

“We had been assigned to Gen. Franklin’s division, which was then lying about four miles northwest of Alexandria, on the borders of Fairfax County, the division headquarters being at Fairfax Seminary, the New Jersey brigade then commanded by Gen. Kearney, and the First New York Cavalry, lying upon the slope of Seminary Hill, south of the Leesburg pike, a brigade commanded by Gen. Newton located along the pike north of the seminary, and a brigade commanded by Gen. Slocum lying northeast of Newton’s brigade, and north of the pike, the camp of its nearest regiment, the Sixteenth New York Volunteers, being perhaps thirty rods from the road. These troops, with four batteries of light artillery, constituted this division in October, 1861. When we arrived, there was a battery of New Jersey volunteers commanded by Capt. Hexamer in the vicinity of division headquarters, a battery in the immediate vicinity of Newton’s brigade, a battery of regulars, D, Second U. S. Artillery, lying near the pike, and opposite, Slocum’s brigade. This battery was located upon a plain, which the road from Alexandria reaches shortly after it crosses the run which makes its way from Arlington Heights southeasterly to Alexandria. The First Massachusetts Battery encamped in a piece of woods on the east side of this run and at the left of Slocum’s brigade. In this camp, which was named Revere, we remained until winter. Our drill-ground was on the plain beyond Newton’s brigade, on the north side of the pike,—of this field we shall have occasion to speak later. The inspection of the artillery by the chief of artillery of the army, and the review of the division, were made upon the high plateau west of the seminary.” — Pvt. A. J. Bennett, First Mass. Light Battery

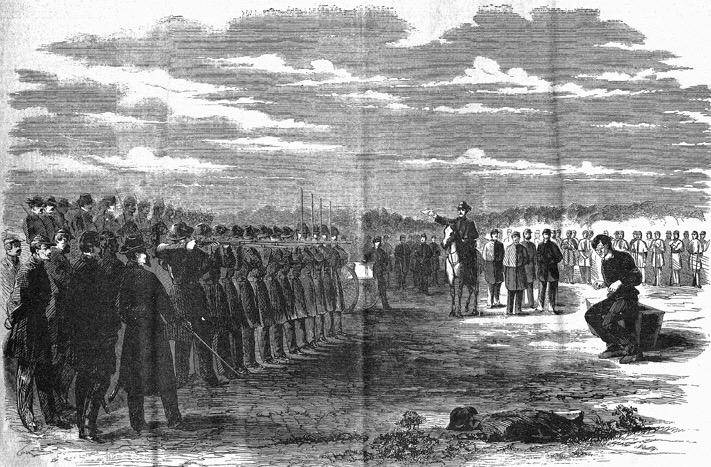

We remained here all winter with plenty of Division reviews, inspections, and camp duties. While here our Division had the 1st Military Execution for deserting. A man named [William Henry] Johnson, 1st New York Cavalry, was on the outer picket line and he left his post and rode towards the rebel lines. When a long distance out, he met a squad in Rebel uniforms and was halted. He said he had deserted. He had his horse, saddle, and bridle, sabre, carbine, and revolver—government property. The officer in charge asked him all kinds of questions as regarding our line, position of picket posts, &c.. He also asked to see his carbine, looked it over, cocked it, and told the man he was a prisoner. The squad was some of our scouts. He was brought in, courtmartialed and sentenced to be shot on the 13th December. The Division was ordered out to see the execution. We were formed on three sides of a square in double lines with the other side open and the grave dug in about the centre of that line…He was brought on the field in a wagon seated on his coffin and a horse with reversed arms (as at a funeral). They entered on the right of the line and passed through all the line. As they passed along, the band of each regiment played a funeral dirge (going to his own funeral). Passing on the left of the line, they drove to the grave. He and his coffin were taken from the wagon, the Judge Advocate read to him the charges, findings, and sentence of the court martial.He was then blindfolded and seated on his coffin. The firing party then stepped up and shot him. The line was then faced to the right and all were marched by close to where he lay. He was buried there. No one was sorry.

In November we had a Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. Over 75,000 troops before the President, foreign ministers, Members of Congress, and others. It was fine. Four batteries were picked out to fire the salute and we were one of the four. Instead of firing so many guns for the salute, we fired so many batteries, all the guns in a battery being fired at once, and counting as one gun. Then the next and so on.

On January 20th, we had one of our men thrown from his wagon and killed. While out after wood, his team, ran away and striking a stump, threw him off. This was the first death in our company. We remained in this camp all winter attending to drill and camp duties.

I will give you an account of what some of our camp duties were. 1st call in the morning at 5.30 when we get up, put on our boots, and are dressed. 5.45 fall in for roll call and served with a dipper of coffee. 6.00 fall in again and clean around the horses, also clean and feed them until 7.00 then breakfast. 8.30 guard mounting when the old guard are dismissed and the new guard go on for 24 hours. They are divided into three reliefs and go on for two hours and off in 4 hours. 9.00 water call when the drivers take the horses to water. 9.30 sick call when all the sick go to the doctor’s tent. 12.30 dinner. 3.30 stable call when the stalls are cleaned. Also horses ed and cleaned. 5.30 evening roll call, 8.00 tattoo roll call. 8.30 taps when all lights are put out. No noise or talk after that. Also about five hours drill beside if the weather is good. Every day field drill, gun drill, or sabre.

After remaining in Camp Revere from October 14th until March 10th, the army started on the march for Centreville and Manassas where the Confederate army were in winter quarters. We had large bell tents called Sibley tents that would hold 12 men each while in winter camp but when we received marching orders, we also received orders to turn them in and draw small ones called shelter tents, one half tent to each man. They would button together. The men would cut three small poles, one for each end and one for a ridge pole, put the tent over and pin it down. Two men could crawl under and sleep.

We had orders also to turn in wheelbarrows, shovels, hoes, pitchforks, small camp stoves and a large quantity of other things we could not carry. I was left in charge of all this property with a guard of six men, one sick man, and a prisoner and two teams. I had to take an account of all the property, turn it in at a government store house in Alexandria, and get a receipt for the same. Then take my men and follow on after the company and report. I overtook them at Annandale on the 14th March on their return from Centreville and Manassas where they had been and Lee’s army had fallen back towards Richmond. When this was found out, the plan of operations was changed ad we (the army) were ordered back to our camp. As we had cold rains on the return march and the men slept on the ground, they suffered very much.

At this time the army was formed into corps, three divisions in a corps. I told you before how many were in a division so you will understand the size of a corps. Our division was the 1st Division, 6th Corps—one of the best in the army and called the “Fighting Sixth.” We lay in camp on our old campground about three weeks, having drill, reviews, and inspections. On the 25th March, General McDowell reviewed and inspected about 50,000 troops. On the 27th, Lord Lyons and other foreign ministers with Members of Congress reviewed about 33,000. Also a review by General McClellan and others.

April 4th last night we received orders to be ready to start in the morning. Were up, tents struck and all packed before sunrise but did not start until about 10 o’clock. I was again left in charge of some stores with two men and orders to turn them in to the quartermaster’s department. The next afternoon at 2 o’clock I took the cars (baggage train) and went about three miles and stoped until six, then thirteen miles and lay on a side track until 10 the next morning in an open baggage car. Then we started again and I found my company at Manassas. Owing to rain and snow the roads were so bad we could not move. There were also various steams of water that had becone so deep we could not cross. We lay in a plowed foeld in a sheet of mud until the 11th when the steam Broad Run, having fallen, the cavalry found a place up the stream where we could cross. The water was up to the axle of the carriages. After passing the run, the fields were so soft we would get all ready and put on whip and spur to the horses and start across, sometimes clear up to the axle, and they would become stuck. Then all the men would get hold and help them out. Each carriage would take a different track in crossing. After getting about two miles beyond the river, we received orders (our Corps) to return to Alexandria, turned back and by a forced march reached Manassas on April 12th, marched again to Fairfax, and camped.

On the 13th reached Alexandria and camped outside the town near Fort Ellsworth. On the 14th we shipped our guns, caissons, and horses on stream transports, and men and baggage on schooners. On the 15th, 16thm and 17th the rest of the corps were being shipped to join General McClellan before Yorktown, he having taken the rest of the army some time before down the river. Sailed early on the 18th, the schooners and some transports in tow of the steam vessels, arriving at Ship Point about three o’clock on the afternoon of the 19th. On the 20th and 21st, unloaded the cavalry and artillery on account of the horses and left the infantry on the transports to await orders, it being understood we were to sail up the York River and attack Gloucester Point opposite Yorktown when McClellan attacks Yorktown. My brothers were in camp about three miles from our camp but I could not go to see them. While laying here the Boys killed quite a number of snakes—Blue Racers. Some of them were four or five feet long. They would crawl in along side the men in the night to keep warm and they would find then in their blankets in the morning.

From the 22nd until May 4th we attended to our regular duties with nothing of interest that I can think of. We could hear the firing every day at Yorktown. On the morning of May 4th, we were having our Sunday morning inspection when the officer commanding the artillery of our division informed us that Yorktown was evacuated and gave us orders to reship. We were all board by midnight. Started up the York River the next morning and reported at Yorktown, remained all night and in the morning, May 6th, we started up river again for West Point, reaching there early in the afternoon. Our horses, arriving first, were landed during the night and our carriages the next morning, May 7th. Some of our infantry that were landed the day before were skirmishing all night. We took position with our guns and were in our first battle. We also had General Sedgwick’s Division with us. The Rebs opened on our troops, steamers and transports. We replied to them and advanced a strong line of infantry and won the day. Our gunboats in the river aided us by rapid firing with large guns. There was a French gunboat came up the river with us to look on. Some of the shots struck quite near her and she run up the French flag and beat to quarters. We remained in harness all night and I was sergeant of the guard and had a gun loaded to fire as a signal if needed.

On the 8th [May], General McClellan and staff arrived, the rest of the army having marched from Yorktown up between the James and York rivers, his right joining our two divisions, remained here the 9th and 10th, the gunboats going further up the river and shelling the woods. On the 11th, moved a few miles and camped, remaining the 12th and moving again on the 13th, camping at Cumberland, remaining the 14th. On the 15th, up at four and ready for the march. Went to the White House—a fine estate belong to Lee. It was a beautiful place, a large number of slaves, and they had nice quarters and workshops. The fields of grain and everything looked fine. The 16th, 17th, and 18th were quiet but we moved again on the 19th. On the 20th and 21st we moved along and on the 22nd remained in camp. Also the 23rd and 24th. On the 25th, we marched again and camped on a plantation belonging to Dr. Gaines who raised grain and tobacco. The Rebs threw a number of shells into our camp today.

For the next few days we lay in camp here and could hear firing at different points along the line. I stood on the brow of a hill and looked down on the Battle of Fair Oaks. Could see the lines move up, hear the cannon and musketry, the yell of both armies as they charged. Also the Battle of Seven Pines. While in this camp I received a letter from your father informing me that in the Battle of Williamsburg (May 5th) that our brother Andrew J. was killed and that your father was wounded in the same battle and was then at Annapolis, Maryland in hospital.

On June 11th we started from camp (leaving the camp standing under guard) at 4 o’clock to relieve another Battery on picket at Mechanicsville where there were a few houses and a ford across the creek. Our troops held one bank and the Rebs the other. We could see them working on earthworks on a hill, but they remained quiet until about 6 p.m. when they opened on us. Each section of the Battery lay quite a distance from the other. The short-distance section was in the road leading to the ford. One long-range section to the right and the other to the left of it. So the lieutenant from right and left would go to the centre and eat with the captain and other lieutenants. As the officers were at supper when the firing commenced and only the sergeants in charge when an aide rode up and ordered us to reply to them. To the fort on the hill was about one mile. I from the left and sergeant Lawrence from the right, each dropped a shell in the breastwork. We heard afterwards from some prisoners that came in that we killed quite a number and dismounted a gun. They soon stopped when they found out what was in front of them. The lieutenant came up running and asked who gave the orders. I told him. Soon the aide returned and told us to stop. The lieutenant told me and I replied, I have a shot in the gun.” He said fire it but don’t load again. I asked could I fire where I wished, He said yes. I dropped the breach of the gun all I could (for elevation), pointed it toward Richmond, which was 4.5 miles and let it go. As the gun would carry about 5 miles, I have often wondered where it went.

We remained here a week laying around the guns, day and night, but we were not troubled again while there. On the [ ] we were relieved, returned to and struck camp, leaving Dr. Gaines’ place and crossing the creek at Woodbury bridge and camped in a field near Fair Oaks. On the 19th, moved a short distance and camped. While here I went among regiments of our line and found [ ] regiments and two batteries from Massachusetts. i found some friends in some of them. The sights I see in passing over the fields of Fair Oaks and Seven Pines were hard. Men thrown into [burial] trenches, some having as many as 100 to 150 in a trench. Many had been only covered as they lay on the ground by throwing dirt up from each side and as the rains had washed parts of them out—arms, legs, face, &c. and those parts were one living mass of maggots. The stench was horrible. And the troops were camped among the graves and had to drink the water. The reason they were buried so was after the battle, there was an awful rain storm and the creek was overflowed and the bodies were under the water. When it went down, they were so bad they could not be handled. The dead belonged to both armies.

For the next week things remained about the same, firing along the lines every day and the regular camp duties. On June 26th the Rebs crossed at Mechanicsville and above, turning our right, where there was a terrible fight—the first one of the Seven Days. General Porter commanding the corps on the right was forced to fall back to Gaines Mills. On the 27th was the Battle of Gaines Mills. We crossed over at Woodbury Bridge and were in the battle in the afternoon. It was very fierce and the loss was large on both sides. At night we crossed back over the creek and took position on the front line remaining all night.

On the 28th, moved back to creek and took position to command another bridge. Troops passing all day and fighting at different points on the line. We held the position all day and on picket at night. Moved back before morning passing through lines of battle. I will explain something here something of the way we were falling back. While say one half of the army were fighting today, the other half formed the second line in rear of the first, ready to support them or take part holding the line all day, and at night the first line passed through the second and formed in their rear, being the supporting line that day. And at night change again from first to second.

On the 29th June was the Battle of Savage Station. When I passed here there were piles of rations—beef, pork, rice, hard bread, &c. Tons of musket and artillery ammunition, shot, shell, &c. All the stores of all kinds the teams could not carry were piled up and set on fire. Also hay and grain. The soldiers were taking the fuses out of the shells, pouring out the powder and in fact, destroying thousands of dollars worth of property. This was a railroad station and that is the reason there was so much property there. We had railroad trains moving what they could and kept them at it so long we could not get back. so the bridge over the creek was burned, the train loaded with stores, the engine started and all run into the creek.

You will form some idea of our wagon train when I tell you if it was put in a single ine, it would reach over 50 miles. We also drove a large head of cattle.

On June 30th, Charles City Cross Roads and White Oak Swamp Battles were fought. We were in the Charles City Cross Roads fight and had it hot. We fired so long and rapid our guns’ breach [became] so hot they would go off when the vent was uncovered. Although we wet the sponge in water, the water passed into the vent honeycombed them so bad that they had to be taken out and new ones put in as soon as we had an opportunity, a man coming from the gun foundry. We fired that day from our long-range guns about one ton from each.

I told you I had a good drilled squad ad we use to see who would gwt the first shot when we received orders to commence firing. I got the first shot and I suppose they fired at my smoke for while loading for the second shot, my No. 3 man at the vent, and my head by his side sighting the gun, a shell passed through him and over my shoulder, spattering the flesh and blood in my face and clothing. After dark we lay around the guns with a skirmish line in front. At midnight the lieutenant told me to wake my men and mount the driver and tell them and the other men not to speak a word or strike a horse and if they became stuck on stumps or in a hole, to leave then and save my horses if I could. If not, leave them. We drove off on the grass without a sound being made. One of our officers (said to be Gen. Kearny) rode up to the picket line and asked for the officer in charge, gave him orders to move the line back and uncover a cross road through a wood as he wished to pass some artillery. the officer, thinking it all right, moved the line and we passed through with everything all right. When we came out on a pike road inside our line, an officer sat on his horse and told us to let them go and we went down the road flying, arriving at Malvern Hill at 4 o’clock in the morning of July 1st, took position in line, and was in the battle part of the time. As our corps was out of ammunition, we received orders to go to the rear. Towards evening we took position for the night.

July 2nd left our position at 2 a.m. and marched to Harrison’s Landing, the troops coming in all day. When we arrived here we entered as fine a field of grain as ever you see, but before night, with the rain and the tramp of troops, it was all gone and was our sea of mud. Thus ended the Seven Days Battles before Richmond—one of the grandest movements of the war. When you think of the country we had to fight over, the large force General Lee brought against us, and we saved our trains and cattle, also artillery and troops.

On the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th, we were in different positions in reforming the lines. On the 8th, President Lincoln with a large staff and guard rode around the lines and received the troops, the gunboats and batteries firing salutes. The infantry built long earthworks and the artillery was placed in them all along the line, the guns being about 17 yards apart and the infantry camped in the rear. A strong picket line was out about 3 or 4 miles. We had drills and other camp duties every day. Otherwise it was quiet until the night of July [ ], when at midnight, the Rebs having brought down some batteries on the other side of the [James] River, opened fire on our gunboats, transports and camps. The gunboats and some batteries near the landing replied. The camps all turned out. It looked fine to see the shells going through the air when they didn’t come too near. In about an hour it stopped and all was quiet again and we turned in. The next day several regiments were sent across the river to destroy some buildings used by then=m for observation and a strong guard left to prevent the move again. A large number of men were dying in the camps every day from the hardships they had passed through but only one died in our camp from fever. Sometimes twenty or thirty dead bodies would pass our camp a day and I suppose the same in other parts of the army. It was very hot while here—from 100 to 115 degrees every day.

We received orders to turn in our guns and draw others of a different kind. We received six light 12-pounders or Napoleon guns, short-range (less than a mile) but the most destructible gun in the service for close fighting. Expecting the guns were ready, we took the horses and only 12 men and went to the landing and then found out we had to put the carriages together, mount the guns, and draw the ashore. Also all the ammunition, It took all day and was a hard job. The glass stood 80 degrees in the shade.

On August 6th, some 30 lb. Parrotts took position on our right. On the 7th Battery, B. Md. Artillery took our position and we moved into camp half a mile in the rear. On the 11th, received orders to be ready, packed up and hitched every day but did not start until the afternoon of the 16th when we crossed the Lower Chickahominy on a pontoon bridge which the gunboats were guarding. On July 18th, passed through Williamsburg (the place my brother Andrew was killed). On the 19th, passed through Yorktown and reached Lee’s Mills on the 20th and were ordered to Hampton. On the 23rd, we shipped our carriages on an old ferry boat that used to run from Boston to Chelsea which reminded us of home.

On the 24th shipped our horses and men on schooners. On the 26th went to Aquia Creek and received orders on the 27th to proceed to Alexandria. Arrived there on the 28th and disembarked, went into camp outside the city near Fort Lyons, and quite near the old camp where my brother was last winter.

On the 29th the Battery was ordered out towards Centreville and as our teams had not arrived, I was left in charge of baggage and stores with a guard until they came. The Battery returned to camp on September 2nd in the night and the next day moved to the old campground of last winter. In camp the 4th and 5th. In the 6th we received orders at 5 p.m. and were on the road at 6 passing over Long Bridge, through Washington and Georgetown on the trot and camping beyond on the Poolesville road (as the Rebs had crossed into Maryland). Remained in camp the next day. Troops passing all day. On the 8th passed through Rockville and at 7 went in position for the night. Marched the next day and camped at night at foot of the Sugar Loaf Mountain. Remained in camp the next day and marched on the following one camping near Buckstown. On the move next day and at noon, halted near Jefferson. Started again and halted near South Mountain, then opened the battery on Crampton Pass, South Mountain, where the Rebs were in a strong position on the side of the mountain with both artillery and infantry. Our battery was engaged part of the time, but being short-range, could only reach part of their line, but other batteries could. Part of our infantry moved on the front and another force moved into the woods and up the side of the mountain and flanked the position, driving them up and over the mountain, taking artillery, baggage wagons, and prisoners. We moved up the hill and camped on the field with the dead and wounded.

We were on the move again on the 17th and could hear rapid firing in the direction of Sharpsburg. We arrived at Antietam Creek at noon where we found a fierce battle going on. We was ordered into line on the right of center where the battle had been fierce, the dead of both armies and wounded lay thick as the field had been charged over two or three ties by both armies. In passing through a cornfield to take position, many a poor soldier (wounded), Union & Reb, would raise himself on his elbow and ask us, “For God’s sake” not to run over him. I can say I never run over a wounded man while in service. I rode by the lead driver and looked out for that. We took position within 500 yards and opened fire, remained on the field that day and the next, engaged or under fire.

On the night of the 18th, could hear the Rebs moving artillery or trains the most of the night, not knowing if they were massing troops for a final charge on our right, or a flank movement in the morning. As soon as daylight on the 19th, our skirmish line was advanced with a strong supporting line and forced the Reb skirmish line back. They soon found they had no support as their army had gone and left them. They threw down their guns and came in as prisoners.

We started after them at once, passing over the field of battle and I must say, I see worse sights here than on any other field I was ever on. Thousands of dead and wounded of both armies, killed in all kinds of ways and positions, and those that were killed at the first of the battle were swollen to twice their size and turned black. The stench was awful (when men are killed in health and full blooded, they turn soon) and the sun was very hot. In all the buildings from the field to the river, we found them filled with their wounded whom they had left behind. Lee’s army had crossed at Williamsport.

On the 21st, camped at St. James College. On the 22nd, moved into camp at St. James College. On the 22nd, moved into camp at Bakersville and remained the rest of the month and until October 9th when we went to Hagerstown and washed up the Battery for repairs and painting, and harnesses for oiling. After getting about half done, we were ordered on picket at Williamsport, put our carriages and harness together and went on the 16th finishing while there. We went out three or four times at midnight (with other troops) to command a bridge expecting a cavalry dash. The nights were very frosty and cold standing on watch. On October 31st we were relieved by the Baltimore Light Artillery and marched to the south side of the Blue Ridge, crossing at Crampton Pass and camping for the night. Then crossed the Potomac at Berlin on a pontoon bridge and entered Virginia once more.

During NOvember there was nothing of interest—only marches taking position in various places. Lots of rain and some snow. General Burnside had taken the place of General McClellan at the latter part of the month. Gen. Hooker’s Division was passing our camp and I run out and watched for the battery your father was in, he having returned to duty. I see him for about half an hour—the first time for eleven months.

December 4th, marched to Belle Plain and went in camp, remaining in camp until the 11th. Some rain and snow. On the 11th we started for Fredericksburg and camped near the river. On the 12th, crossed the Rappahannock on a pontoon bridge below the city (called Franklin’s Crossing) and went in position near the Barnard House. The day was foggy but about 3 o’clock it lifted and the Rebs opened on us and there was some brisk fighting. At night it stopped.

Early the next morning, the 13th, the firing was rapid and lively on both sides. At noon we moved and took position on the right of the left wing of our army, when the whole of the infantry line (in that wing) advanced towards the railroad and a fierce infantry fight took place. The Rebs moved a battery to rake the line, when our battery opened on their and blew up a number of heir limbers and the loss of life must have been large. We soon silenced that battery.

Our troops were repulsed with a large loss in killed and wounded and they fell back to their old place in line. Towards evening the opened a cross fire on us from a battery near the town. Their 1st shot smashed a wheel on a gun limber, took off a sergeant’s leg, and a private’s arm. Some horses killed and wounded. On the 14th and 15th lay in position with few shots from either side, both watching for a move from the other.

On the night of the 15th all the army fell back across the river on the pontoon bridges. These were covered with hay to deaden the sound. We were all across and the bridges up before daylight which surprosed the Rebs who expected to see us before them in the morning. Our battery was the last to cross, being with the rear guard. We had a large loss and no gain in this battle. We then returned to the same camp occupied before the movement. Remained here until the 19th when we moved and camped near White Oak Church on the Belle Plain Road. Nothing of interest during the rest of December—only the same as when we are in camp long. On the 28th I got a pass, mounted, and went out to find your father’s company. After riding about all over the army, I found him.

From January 1st to 20th, we were in the same camp building brush stables for the horses and attending to other camp duties. On the 20th, left camp at noon and marched across country striking the Warrenton Pike near Falmouth where we camped for the night. A cold rain all night and for the next three days. In the morning we were soaking and puddles of watrer where we lay. We had hard work to move our carriages, the mud was so deep. We had to take the horses from one carriage and put them on another, then return for the others. Sometimes we had from 8 to 28 horses on one carriage. Pontoon trains, baggage wagons, siege guns, and ambulances were struck fast in the mud. Mules and horses were mired and became so weak as to fall over in the mud and drown. I had to take a mounted detail of 16 men, go back and find the forage train, get a bag of oats, and put it in front…[the remainder is missing]