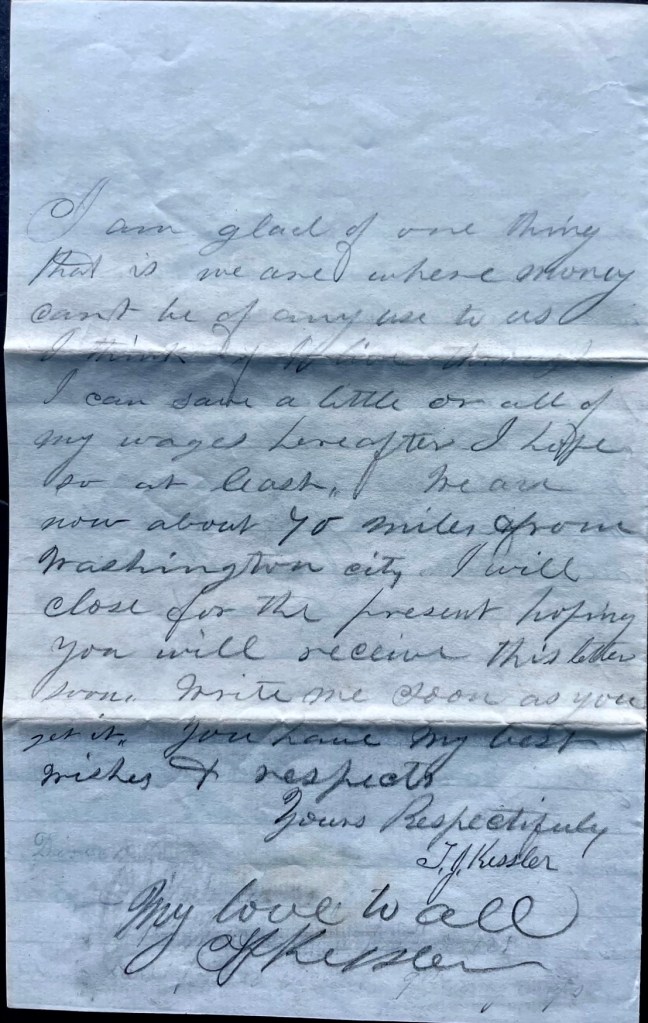

The following letters were written by Thomas Jefferson Kessler (1843-1901), the son of Abram P. Kessler (1816-1864) and Mary L. Wirt (1819-1886) of Goshen, Elkhart county, Indiana. An obituary informs us that Thomas was born in Summit county, Ohio, in 1843, and came to Elkhart county, Indiana, with his parents when he was only five years old. They settled on a farm in Washington township. In the spring of 1863 “he enlisted in the First Regiment of the Michigan Sharpshooters. The regiment was assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, of the Army of the Potomac, Gen. Wilcox commanding. He was in the battle of Petersburg when his commander captured that place. When the war closed, Mr. Kessler returned to Goshen and was employed as clerk by Deferees & Company. He was married in the fall of 1867 to Miss Hattie C. Barnes and one son, Guy B. Kessler, was born to them. Mr. Kessler was in 1872 appointed to the U. S. railway mail service with a route on the Lake Shore road. He held the position about 15 years, when he resigned…”

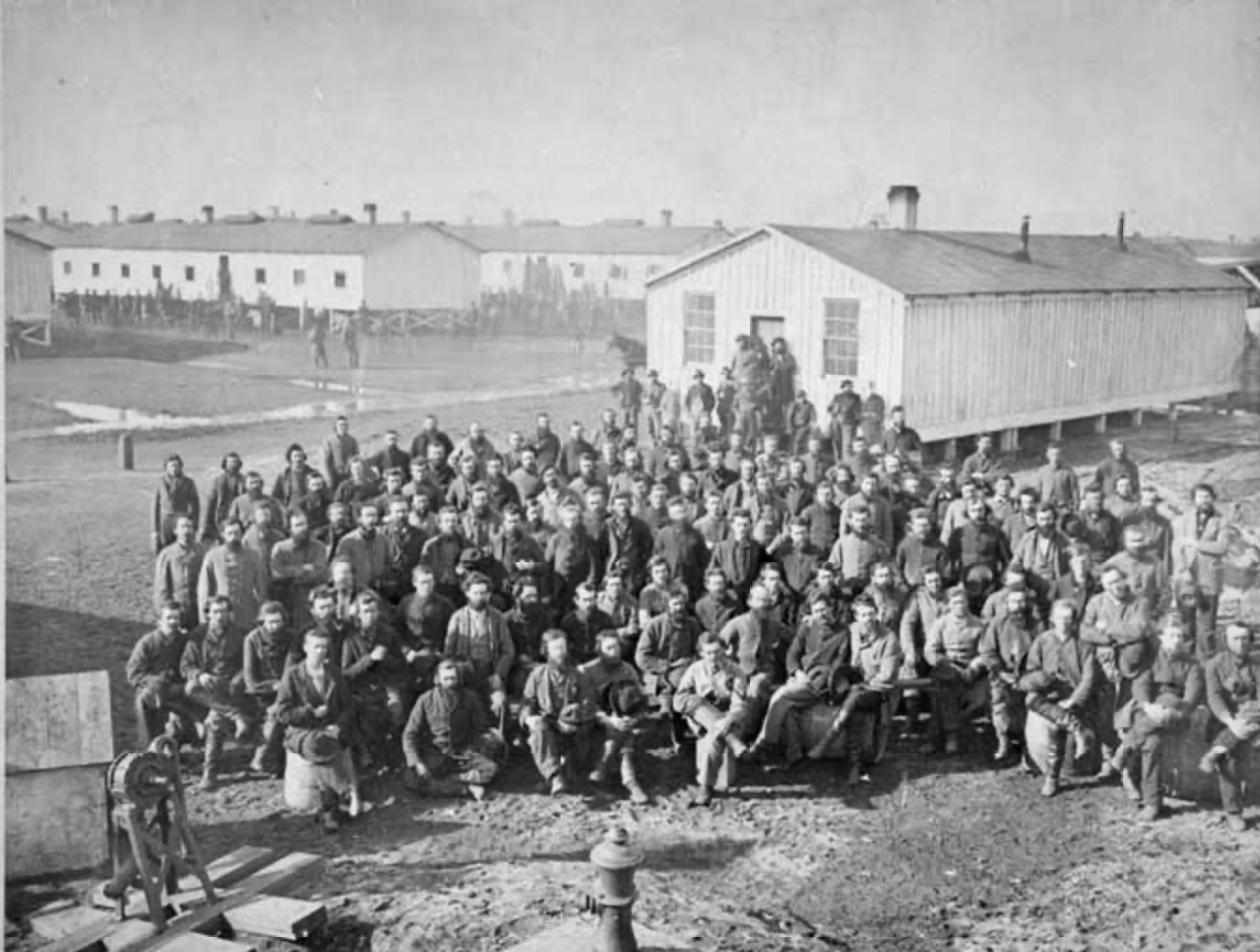

An examination of Thomas’ military records indicates that he enlisted on 28 June 1863 and was mustered into Company G of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters on 8 July 1863. He completed his service and mustered out on 28 July 1865 in Washington, D.C. The letter from Camp Douglas (near Chicago) was where the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters served as prison guards until 7 March 1864, at which point they were reassigned to join the Army of the Potomac for the Overland Campaign. The content of this letter serves as a primary source, offering insights into the operations and conditions of the camp and its inmates during the period overseen by Colonel DeLand, thus contributing to the existing body of knowledge documented by institutions such as the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation.

[Note: This letter is from the private collection of Greg Herr and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Letter 1

Camp Douglas

December 9th 1863

Dear Sister,

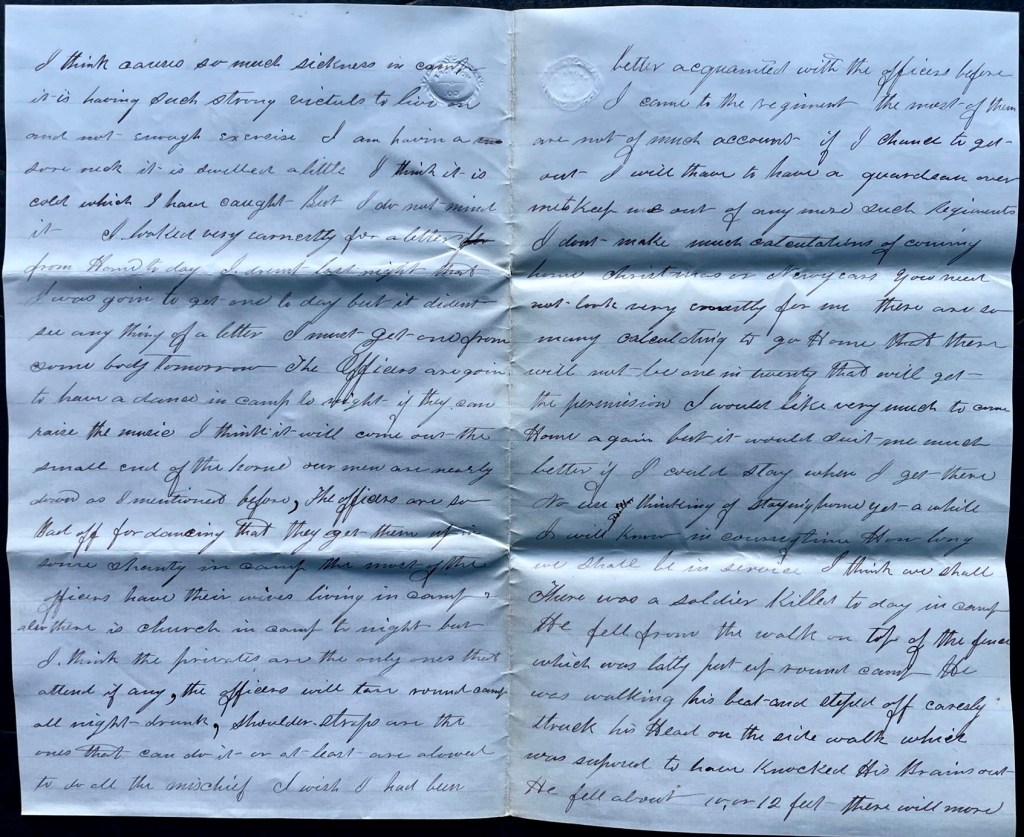

I spend this evening in writing you a few lines. I received your letter a few days since. I think I answered it in Henry’s letter. I received his letter before he got mine. I have no news special of interest to relieve the monotony of the times and will write such news as will come before me to pass away the present night. I am feeling pretty well but the majority of our Band Boys are not able to be up. There is four of them that are pretty sick tonight. The complaint is the diarrhea and has run them down very fast. I have been somewhat down for a few days with the same complaint but have got nearly over it. I do not know what causes this sickness unless it is the pleasant weather we have. I can’t compare it to anything else. Another thing which I think causes so much sickness in camp, it is having such strong victuals to live on and not enough exercise. I am having a sore neck. It is swelled a little. I think it is cold which I have caught but I do not mind it.

I looked very earnestly for a letter from home today. I dreamt last night that I was going to get one today but I didn’t see anything of a letter. I must get one from somebody tomorrow. The Officers are going to have a dance in camp tonight if they can raise the music. I think it will come out the small end of the horn. Our men are nearly down as I mentioned before. The officers are so bad off for dancing that they get them up in some shanty in camp. The most of the officers have their wives living in camp. Also there is church in camp tonight but I think the privates are the only ones that attend if any. The officers will tear around camp all night drunk. Shoulder straps are the ones that can do it or at least are allowed to do all the mischief. I wish I had been better acquainted with the officers before I came to the regiment. The most of them are not of much account. If I chance to get out, I will have to have a guard on over me to keep me out of any more such regiments. I don’t make much calculations of coming home Christmas or New Years. You need not look very earnestly for me. There are so many calculating to go home that there will not be one in twenty that will get the permission. I would like very much to come home again but it would suit me much better if I could stay when I get there. No use of thinking of staying home yet a while. I will know in course of time how long we shall. be in service. I think we shall.

There was a soldier killed today in camp. He fell from the walk on top of the fence which was lately but up round camp. He was walking his beat and stepped off carelessly, struck his head on the side walk which was supposed to have knocked his brains out. He fell about 10 or 12 feet. There will more get the same fix if they are not on the lookout. It is a very risky undertaking to walk in a dark night. Also a very cold place up in the air about 12 feet high.

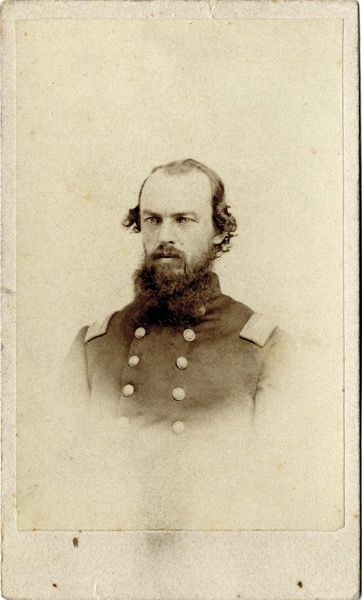

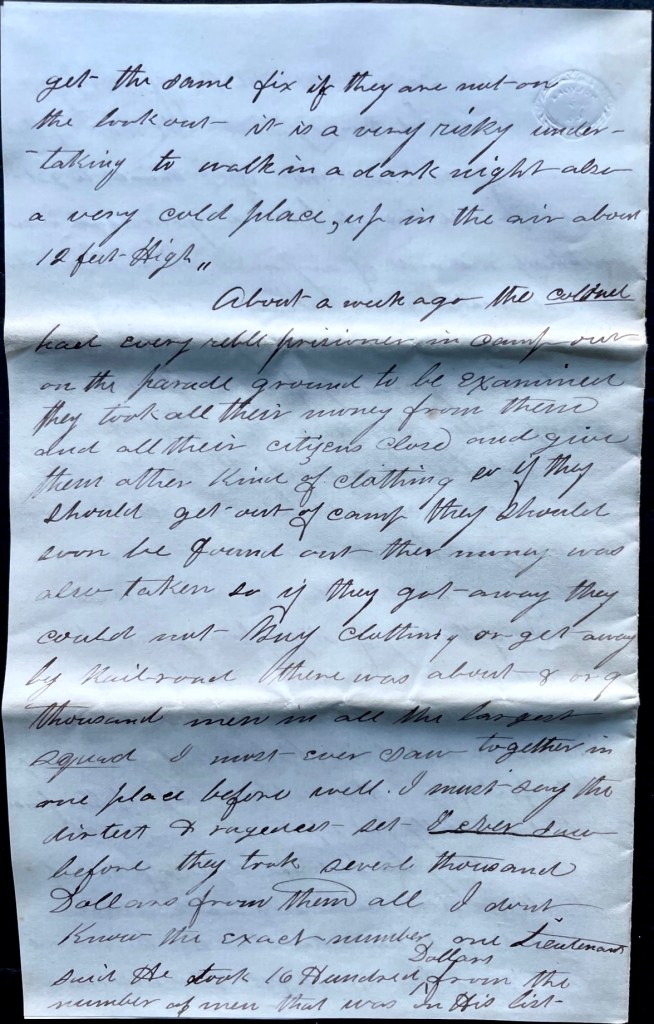

About a week ago the Colonel had every rebel prisoner in camp out on the parade ground to be examined. They took all their money from them and all their citizen’s clothes and give them other kind of clothing so if they should get out of camp, they should soon be found out. Their money was also taken so if they got away, they could not buy clothing or get away by railroad. There was about 8 or 9 thousand men in all—the largest squad I most ever saw together in one place before. Well I must say [they were] the dirtiest and raggediest set I ever saw before. They took several thousand dollars from them all. I don’t know the exact number. One Lieutenant said he took 16 hundred dollars from the number of men that was on his list and if all the rest done as well as he did, they done well enough. It took all the officers nearly a day to go over them. All this money goes to the government or to this post fund of Camp Douglas. They also tore up the floor in their barracks to keep them from digging out underground. The found a good many arms while they was searching their tents—revolvers, bayonets, hatchets, &c. They had made up their minds sometime to attack us when they got all ready and all their points accomplished but I think there is no danger of their doing anything to injure us now.

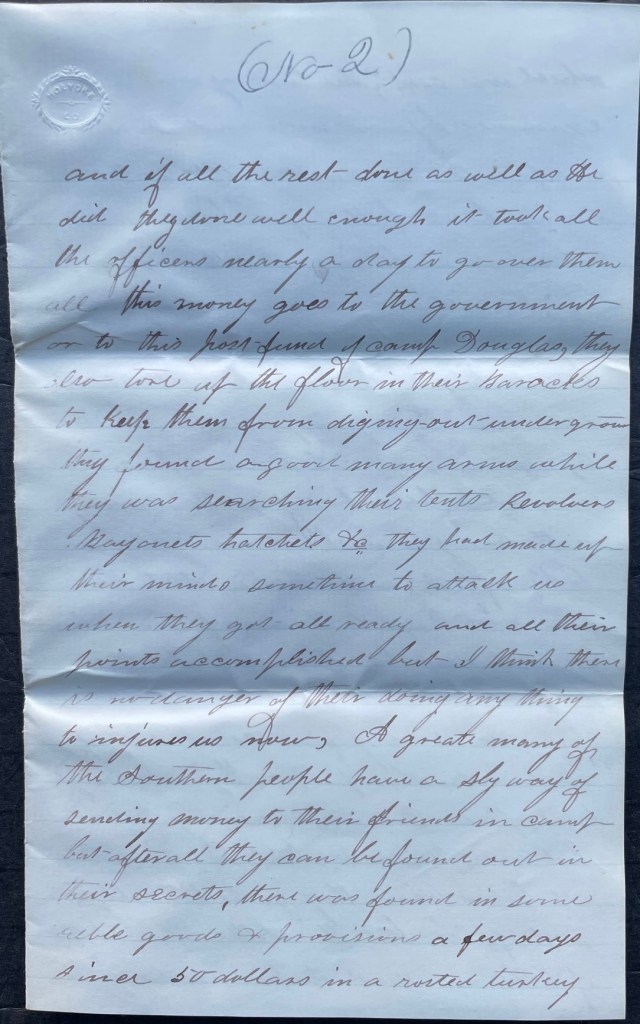

A great many of the Southern people have a sly way of sending money to their friends in camp but after all they can be found out in their secrets. There was find in some rebel goods & provisions a few days since. 50 dollars in a roasted turkey which was sent. The turkey was examined by our men and there was found in a small bottle in the turkey’s breast full of greenbacks which was expected to be smuggled through all safe. There is some more coming about the same way but the Mr. Rebs will not be able to get it. The rebels in the South send letters here giving all the secrets they send in goods and provisions. There is supposed to be a box of goods coming with money in it. There was a letter written to the effect. A Mother wrote to her son and says to him as follows, “When you get your box of goods, take the box and make kindlin’ wood of it. Cut it very fine. Count every nail. Look sharp, &c. This is enough to suspicion that there is money round. But as it happens, Mr. Colonel examines all letters before they go to the rebel post office but the letter which I speak of will not reach the prisoner nor the money which was sent him. The money is supposed to be morticed into the side of the box, &c. This seems rather bad to look at the matter and their being destitute of means to keep them from freezing. “But nevertheless it is nothing more than they deserve.” Let them behaves themselves as they ought and they would not need suffer the consequences.

Our people in the North speak of the southern classes of people not being enlightened to any extent whatever. They are very much mistakened. These are some of the best educated men in the camp among prisoners I ever saw. There are lawyers, doctors, &c. &c. that a great deal better qualified for business than the most of our men in camp. I presume [if we were] to take a fight, they could whip us also. I do not wish you to understand these as my principles, and further not to think I have turned to be a rebel since we have been in Camp Douglas. These are not my principles.

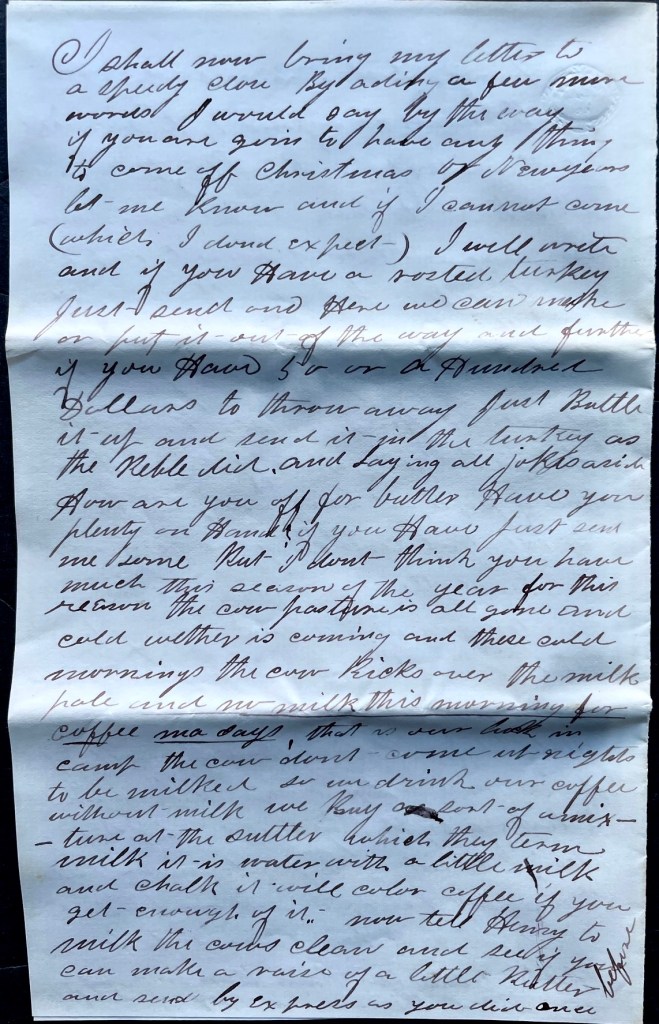

I shall now bring my letter to a speedy close by adding a few more words. I would say by the way if you are going to have anything to come off Christmas or New Years, let me know and if I cannot come (which I don’t expect), I will write and if you have a roasted turkey, just send oner here. We can make or put it out of the way and further if you have 50 or a hundred dollars to throw away, just bottle it up and send it in the turkey as the Rebel did. And laying all jokes aside, how are you off for butter? Have you plenty on hand? If you have, just send me some. But I don’t think you have much this season of the year for this season the cow pasture is all gone and cold weather is coming and these cold mornings the cow kicks over the milk pail and no milk this morning or coffee now days. That is our talk in camp. The cow don’t come at nights to be milked so we drink our coffee without milk. We buy a sort of a mixture at the sutler which they term milk. It is water with a little milk and chalk. It will color coffee if you get enough of it. Now tell Henry to milk the cows clean and see if you can make a raise of a little butter and send by Express as you did once before.

I see I had not room enough on the last sheet to close my letter. I want you to write to me soon as you get this. Don’t wait so long and when you write, give me all the news there is going on—who goes home with the girls and who don’t, and who can’t go. Henry says he has got what he wanted for a long time and that was a drum. I expect he does nothing else but drum all the time. He had better come and join the Michigan Sharpshooters. I think if Henry goes to Hiram Rex School this winter he will be able to take charge of the Army of the Potomac next spring. I think a wooden man would answer about as well. I know it in the Weikle District. It is not fair for all the cowards to stay at home and take advantage of those who are gone to fight for their country in the manner of taking schools at one dollar per day while they ought to be soldiering for 18 dollars per month.

I hope the draft will just come and clean out 3 or 4 boys of every family in that neighborhood. They will make just as good soldiers as anybody else that is not as wealthy. I would like to see some of them put on airs with a suit of Uncle Sam’s clothes. I would stand and blow Hail Columbia for a week without anything to eat. I think if there is a draft this spring, it will cut pretty close to old Kinney’s gate. “By hell, I did not dink she would come so soon.” 1

Well, I expect the dance is going off pretty rough by this time and about half drunk.

I received a letter from Jim Dever a few days since. It was a long one and a good one. I expect another soon. I expect you are going to school this winter at Bristol. If you are, go ahead and get ready and go. Mr. Hanks is a good teacher. He can learn you much as Mrs. Babb 2 can and a little more and not charge you as much either. Write whether Ma has come home or no. See if you can write me a letter large enough to cost two postage stamps. Tell Henry to write again. He makes a very good letter writer. No more at present. Answer soon. My respects to all. — Thomas J. Kessler

Thomas J. Kessler, 1st Regiment S. S., Brass Band, Camp Douglas, Chicago, Illinois

To E. Kessler, Bristol, Elkhart, Indiana

Answer immediately. Truly yours, — T. J. K.

1 Thomas may have been referring to Frederick G. Kinney (1804-1879), a native of Union (now Snyder county), Pennsylvania, who came to a 200-acre farm four miles north of Bristol, Elkhart county, Indiana, in May 1849. He raised seven children and by his thrift and accumulated wealth, provided them all with homes of their own. His four oldest children were all boys of military age, Benjamin (b. 1835), Frederick (b. 1838), George (b. 1842), and Lewis (b. 1845). It does not appear that any of them served in the Union army.

2 This was probably Ann Eliza (Shields) Babb (1825-1916). She was daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Hector Shields. After her education she was a school teacher in Peru, Ohio for several years. She married Benjamin Babb on 24 Dec 1851 after which they moved to Elkhart, IN where they lived the rest of their lives. She worked with him in their bookstore for many years and gained a reputation of being an encyclopedia of general knowledge. She was also a student of the Bible and was often called on to give Bible studies. The couple had no children.

Letter 2

Warrenton Junction, Virginia

May 1st 1864

Dear friends,

I suppose it has been some time since you heard from me and as it is about the last opportunity I shall have to write you, I take pleasure to drop you a few lines this Sunday eve. I am well at present and hope this will find you all the same. I received Pa’s letter yesterday morning. Was forwarded from Annapolis to me. Was glad to hear from home. I wrote one and sent it or mailed it at Fairfax. I suppose you will get it.

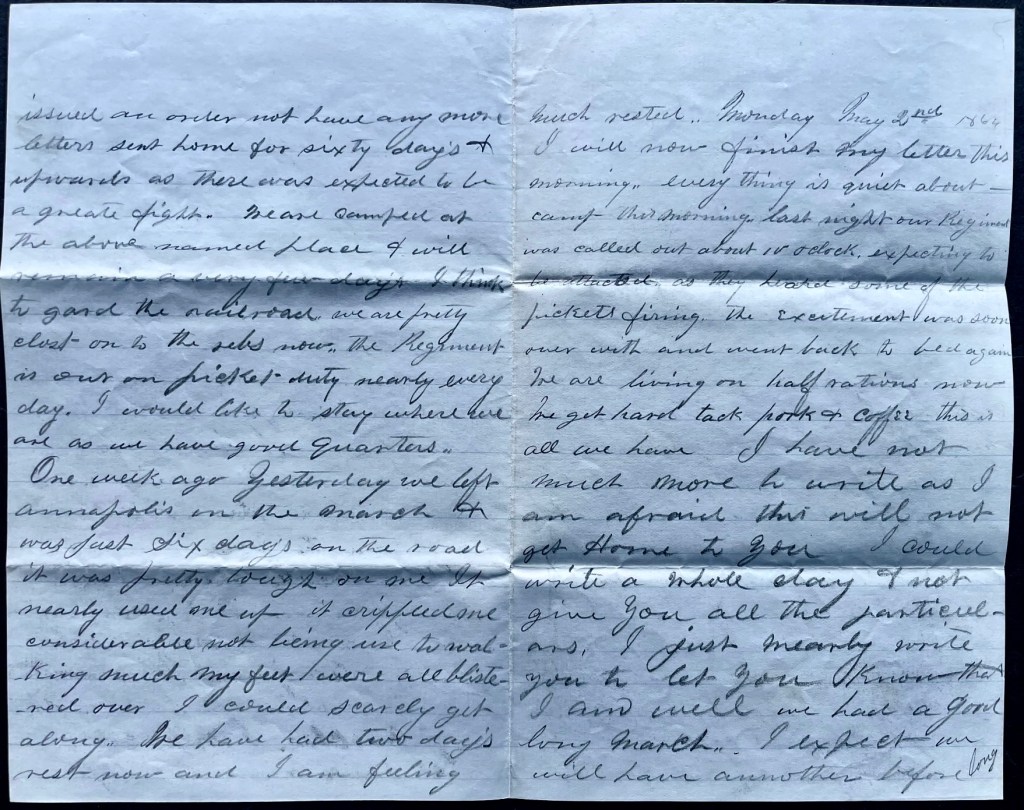

As I said, it would perhaps be the last time for a good while as Gen. Burnside issued an order not [to] have any more letters sent home for sixty days & upwards as there was expected to be a great fight. We are camped at the above named place & will remain a very few days, I think, to guard the railroad. We are pretty close on to the rebs now. The regiment is out on picket duty nearly every day. I would like to stay where we are as we have good quarters.

One week ago yesterday we left Annapolis on the march & was just six days on the road. It was pretty tough on me. It nearly used me up. It crippled me considerable, not being use to walking much. My feet were all blistered over. I could scarcely get along. We have had two days rest now and I am feeling much rested.

Monday, May 2, 1864. I will now finish my letter this morning. Everything is quiet about camp this morning. Last night our regiment was called out about ten o’clock expecting to be attacked as they heard some of the pickets firing. The excitement was soon over with and went back to bed again. We are living on half rations now. We get hard tack, pork & coffee. This is all we have.

I have not much more to write as I am afraid his will not get home to you. I could write a whole day and not give you all the particulars. I just merely wrote you to let you know that I am well. We had a good long march. I expect we will have another before long. I am glad of one thing—that is we are where money can’t be of any use to us. I think if I live through, I can save a little or all of my wages hereafter. I hope so at least.

We are about 70 miles from Washington City. I will close for the present hoping you will receive this letter soon. Write me soon as you get it. You have my best wishes & respects. Yours respectfully, — T. J. Kessler

My love to all.