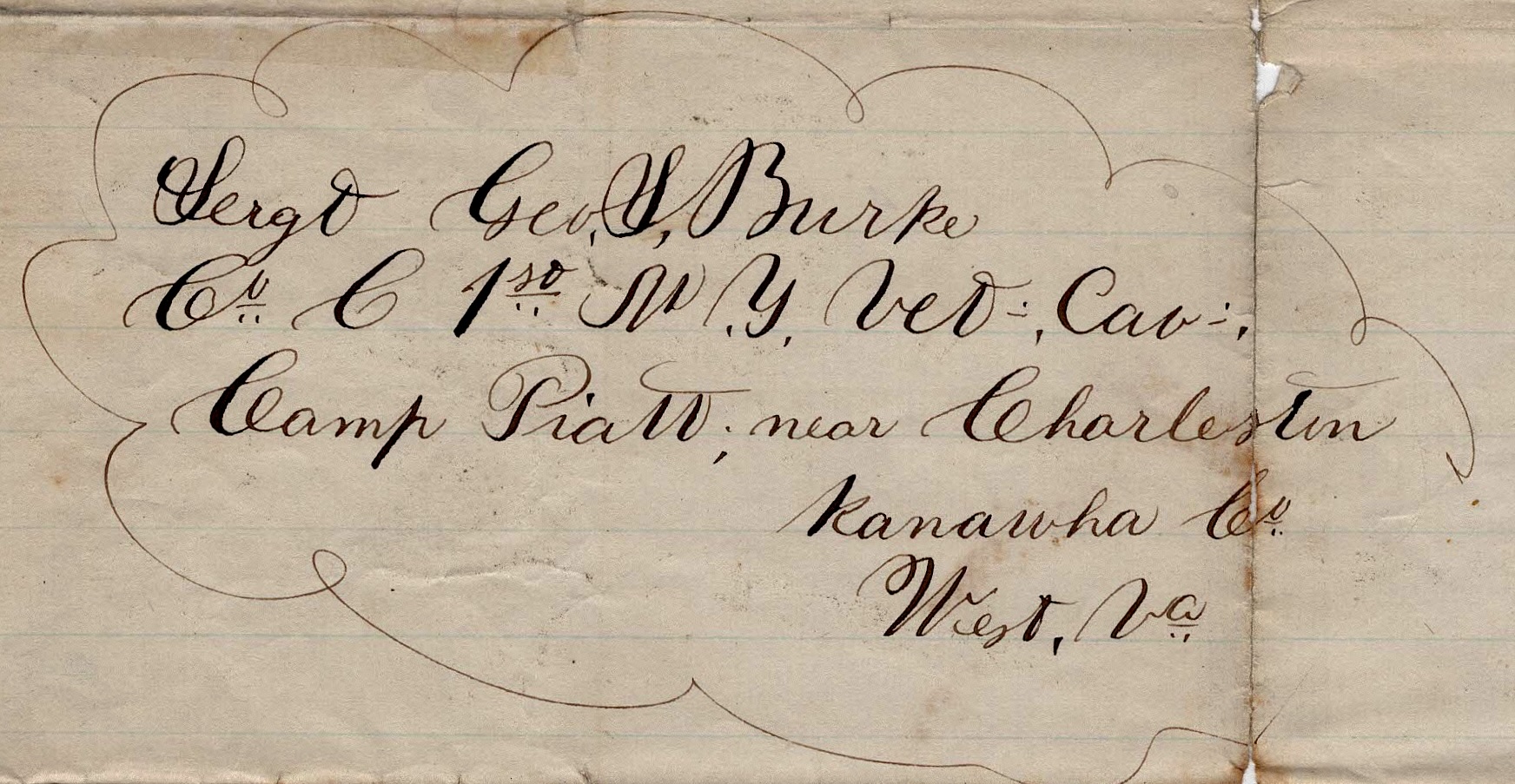

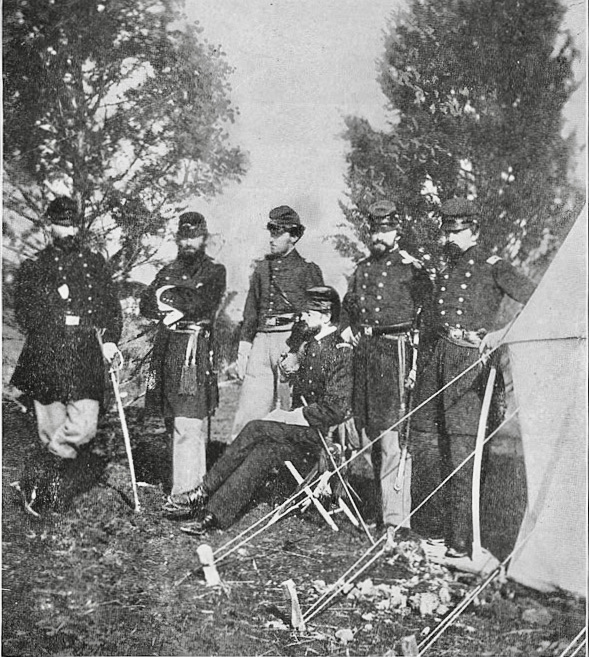

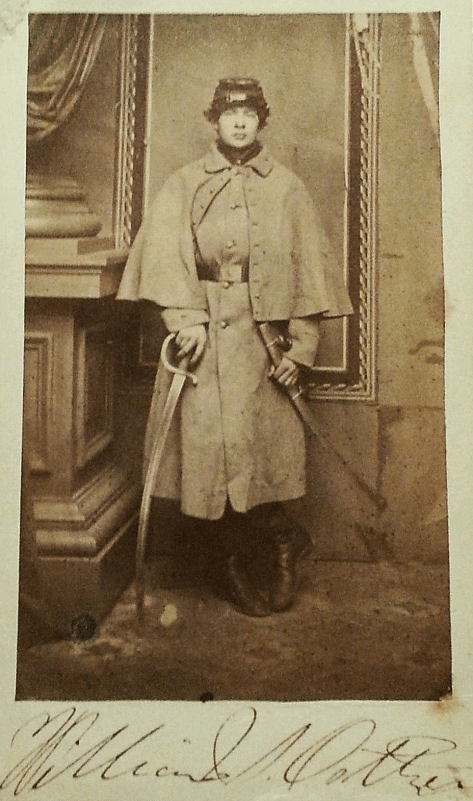

The following letters were written by George S. Burke (1838-1931), the son of Thomas Burke (1799-1879) and Mary Burke (1806-1877) of Irondequoit, Monroe county, New York. George was born in Morristown, New Jersey, on 11 December 1838, and came with his parents to Irondequoit in 1842. When he was 23, he enlisted in Reynolds Battery (Co. L, 1st New York Light Artillery).

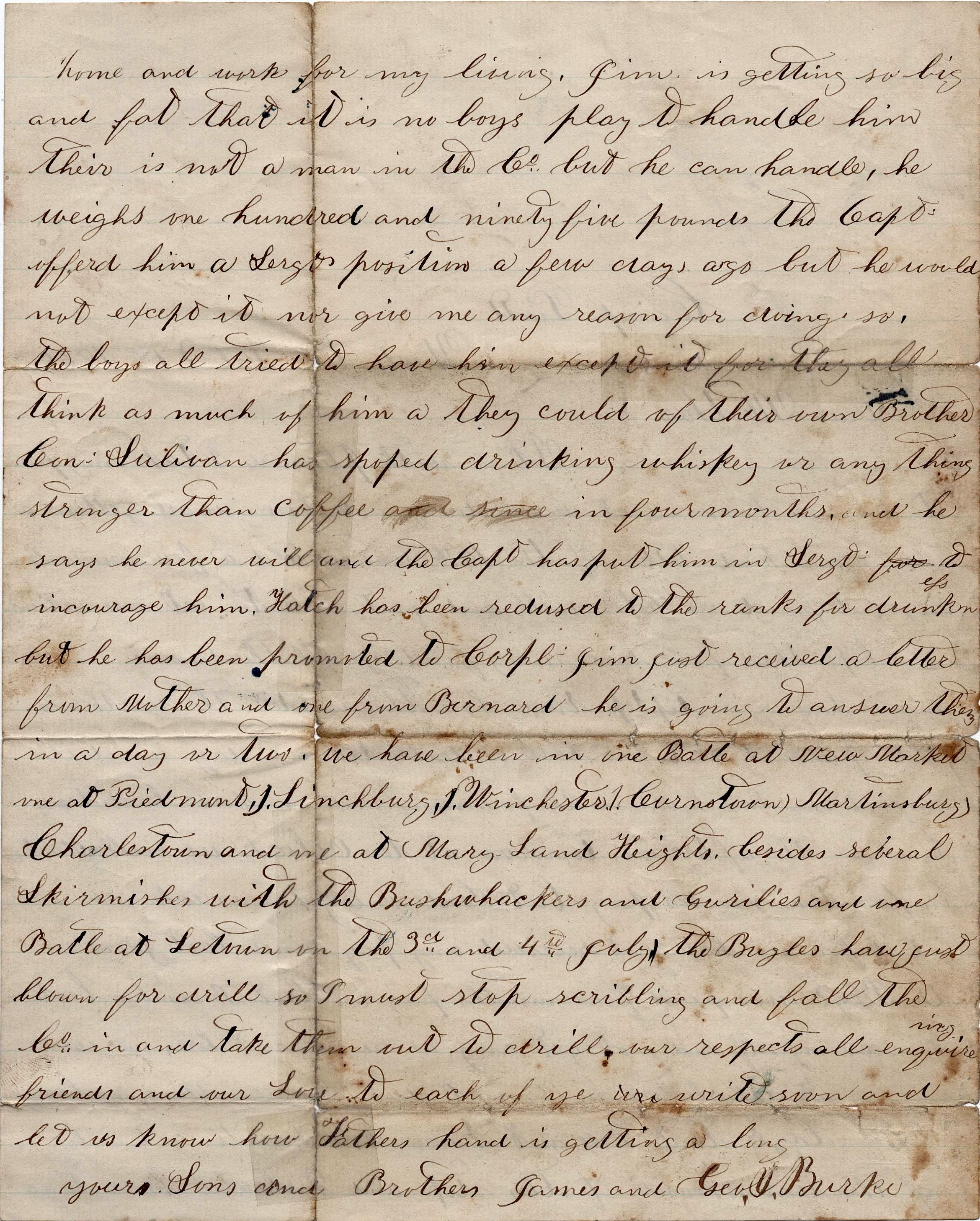

After about a year in the service, he contracted typhoid fever and was sent to Cliffburne Barracks Post Hospital (Depot Camp Invalid Corps) in Washington D. C. where he was subsequently discharged on a surgeon’s certificate in mid-December 1862. After regaining his health, George reenlisted in August 1863 at Rochester, New York, and was mustered in as a private on 10 October 1863, into Co. C, 1st New York Veteran Cavalry with his younger brother James by his side. He was mustered out on 20 July 1865 at Camp Piatt, West Virginia, after receiving promotions to corporal 7/1/1864 and sergeant 9/1/1864.

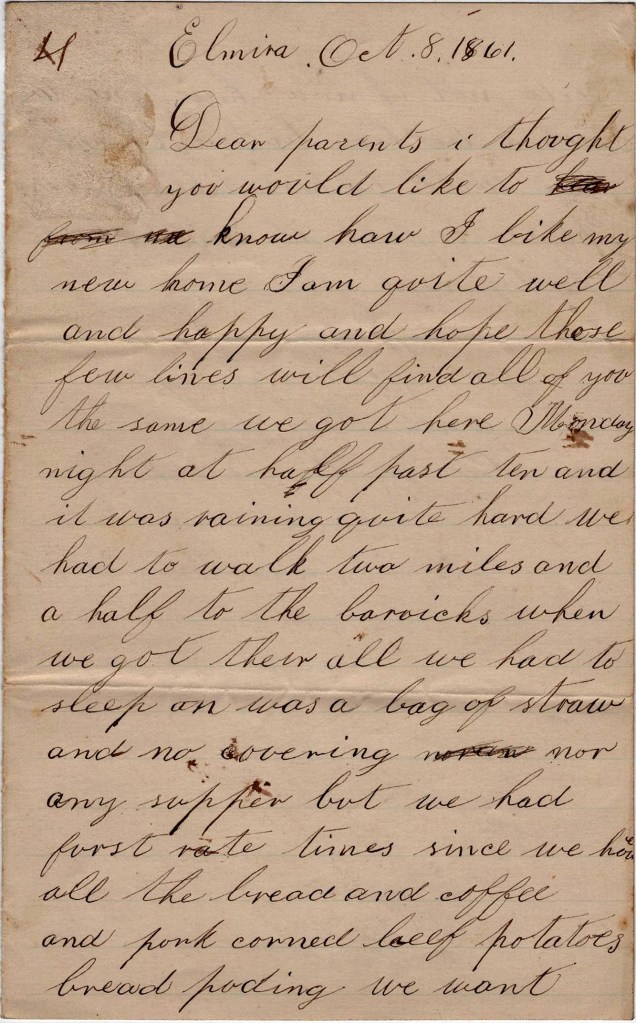

Letter 1

Elmira, [New York]

October 8, 1861

Dear Parents,

I thought you would like to know how I like my new home. I am quite well and happy and hope these few lines will find you all the same. We got here Monday night at half past ten and it was raining quite hard. We had to walk two miles and a half to the barracks. When we got there, all we had to sleep on was a bag of straw and no covering nor any supper but we had first rate times since. We have all the bread and coffee and pork, corned beef, potatoes and bread pudding we want.

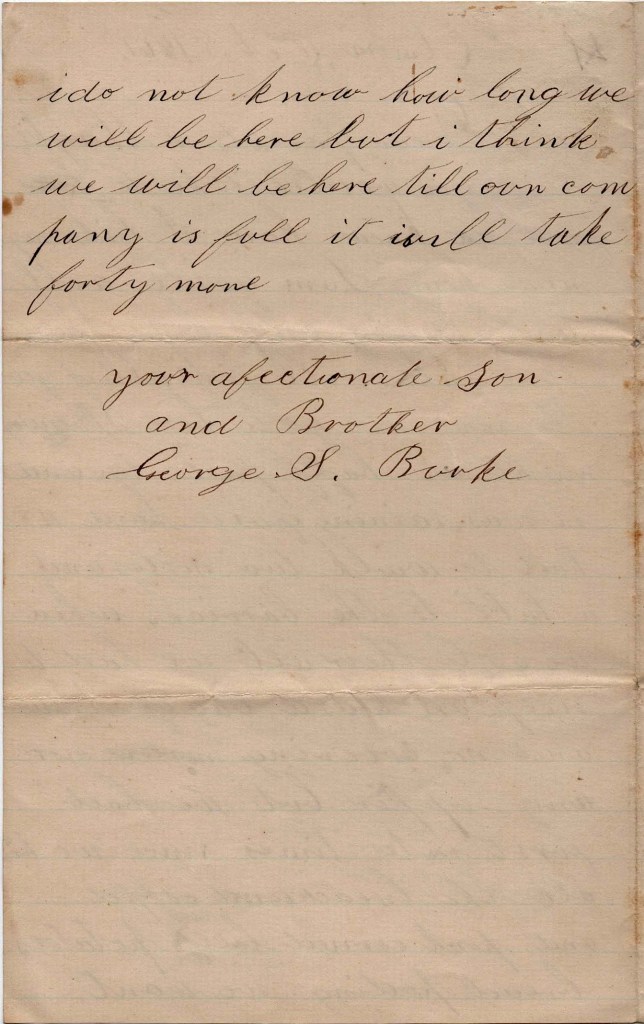

I do not know how long we will be here but I think we will be here till our company is full. It will take 40 more. Your affectionate son and brother, — George S. Burke

Letter 2

Elmira [New York]

October 11th 1861

Dear Parents,

I am quite well and happy and hope these few lines will find you the same. We have plenty to eat and nothing to do but drill about two hours a day. We have not got our uniforms yet but we are expecting them every day. We have all we want of beef, mutton, pork, liver, potatoes, bread, coffee, butter, rice, mush and milk, molasses, vinegar, pepper and salt, and beans.

We do not know how long we will remain here. We heard Tuesday that we would stay here for four or five weeks but I heard last night that we were going to Washington the middle of next week and from that to Missouri. But we can’t tell when we will go or where we will go for one day we hear one thing and the next day something else. We all passed inspection except [Herman] Riley Benedict and Squire Bardwell’s son. Benedict was too young and Bardwell had a fever sore on his shin. Riley will give you ninety cents that I lent him. I have got everything that I want.

Direct your letter to George S. Burke, care of Capt. J. A. Reynolds, Barracks No. 3, Elmira, New York, and he will bring it to me.

I got a paper this morning. All of them down here say that our company is the best looking and the best behaved company there is here. There is 23 companies and about as many more half a mile from here. I would like to know if ye heard from John and if ye did, how he is. Goodbye for a while. Your affectionate son and brother, — George S. Burke

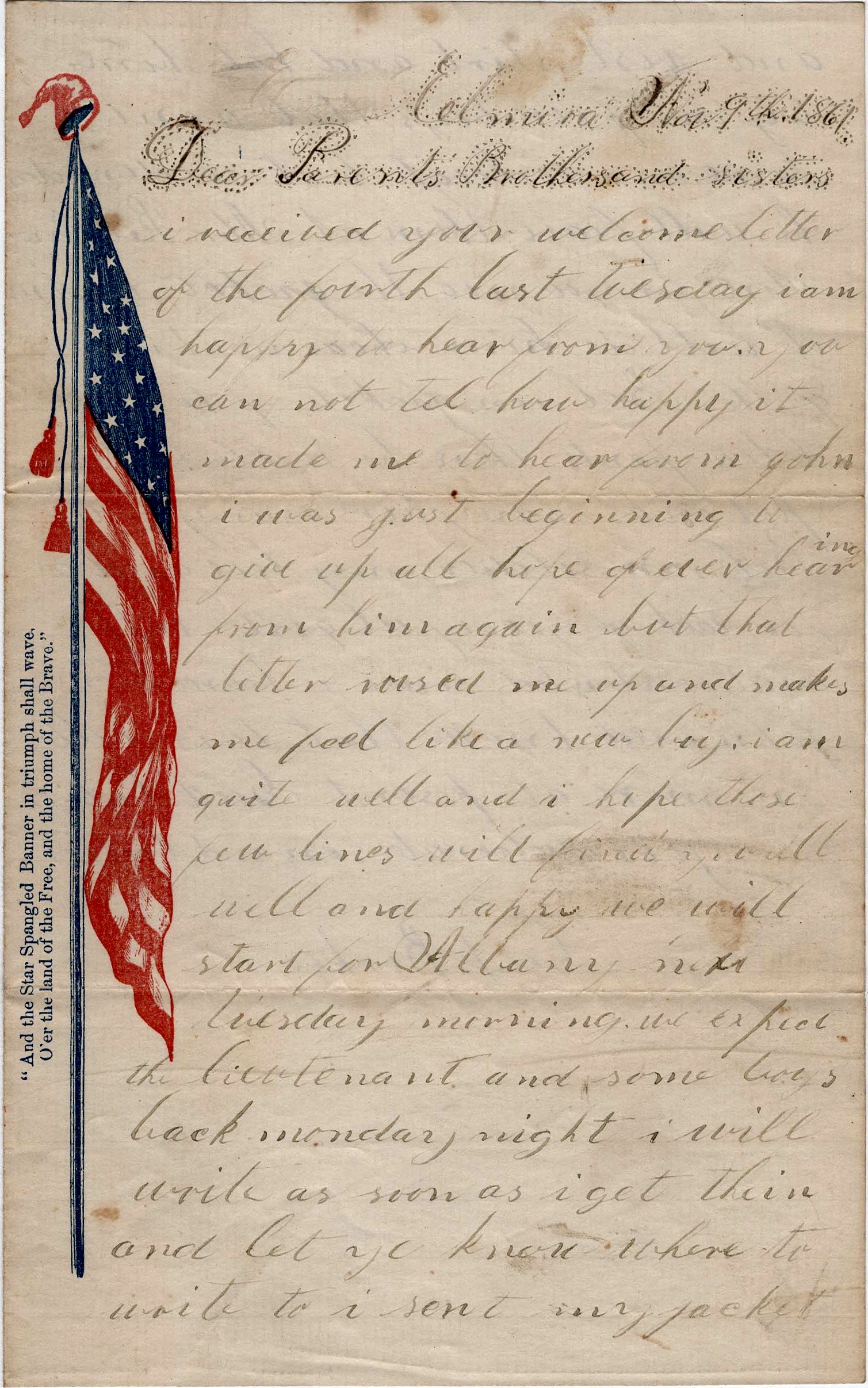

Letter 3

Elmira [New York]

November 9, 1861

Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters,

I received your welcome letter of the 4th last Tuesday. I am happy to hear from you. You cannot tell how happy it made me to hear from John. I was just beginning to give up all hope of ever hearing from him again but that letter roused me up and makes me feel like a new boy. I am quite well and I hope these few lines will find you well and happy.

We will start for Albany next Tuesday morning. We expect the lieutenant and some boys back Monday night. I will write as soon as I get there and let you know where to write to. I sent my jacket and vest, shirt and hat home by one of our boys that went home on a furlough last Wednesday. He will leave them at Mr. Reynolds’ store for you. Give the jacket to Jim. It will do him charm [?] It is one of the Bull Run jackets. If he gets blue pants, then he will be able to put on as many airs as any of the Bull Run soldiers.

My love and a [kiss] for each of you. I feel quite happy and contented since I heard from John and know that he is well. No more at present. Goodbye. Your affectionate son and brother. — George S. Burke

Letter 4

Washington [D. C.]

December 30, 1861

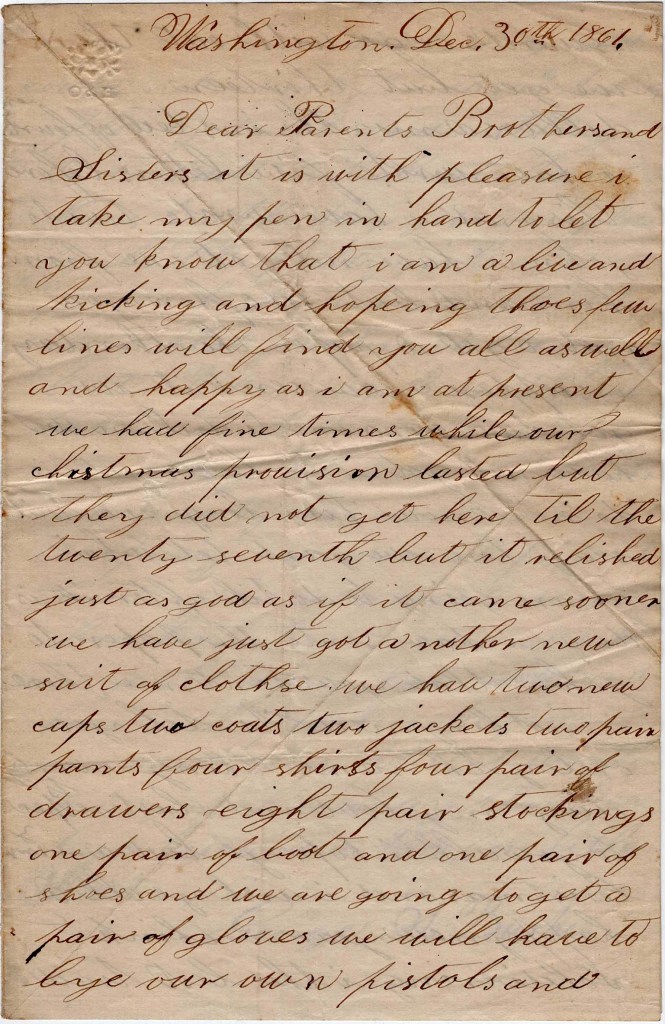

Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters,

It is with pleasure I take my pen in hand to let you know that I am alive and kicking and hoping these few lines will find you all as well and happy as I am at present. We had fine times while our Christmas provision lasted but they did not get here till the 27th, but it relished just as good as if it came sooner.

We have just got another suit of clothes. We have two new caps, two coats, two jackets, two pair pants, four shirts, four pair of drawers, eight pair of stockings, one pair of boots, and one pair of shoes, and we are going to get a pair of gloves. We will have to buy our own pistols and swords or go without them. We get but 13 dollars a month instead of 14. I have wrote five letters before this and I have wrote two to John. I have not got one from him and but two from you. I got a paper the other day. I suppose you sent it.

We have got two cannons to drill on. We have not got our horses yet. I do not know how long we will stay here. We can’t tell what we are going to do till after it is done.

I have sent the paper to John that you sent me. There is nothing new to tell you—only the same thing every day.

My love and best respects to all. I hope ye had a Merry Christmas and I wish ye all a Happy New Year. I think soldiering is the best trade I ever was at. We could not wish for easier times—plenty to eat and nothing to do but drill about four hours in the day. Give my love to all the pretty girls and a kiss for each of you. I am glad to hear that Father’s shoulder is better.

Riley [Benedict] is sick in the hospital but I think he will [be] out in a few days. We have one hundred and twenty-two men in our company.

No more at present. From your affectionate son and brother. Where is Sis and what are ye all doing and how is the potatoes keeping? We have very pleasant weather. It is more like May than December. Goodbye. A kiss for little Ann. — George S. Burke

Letter 5

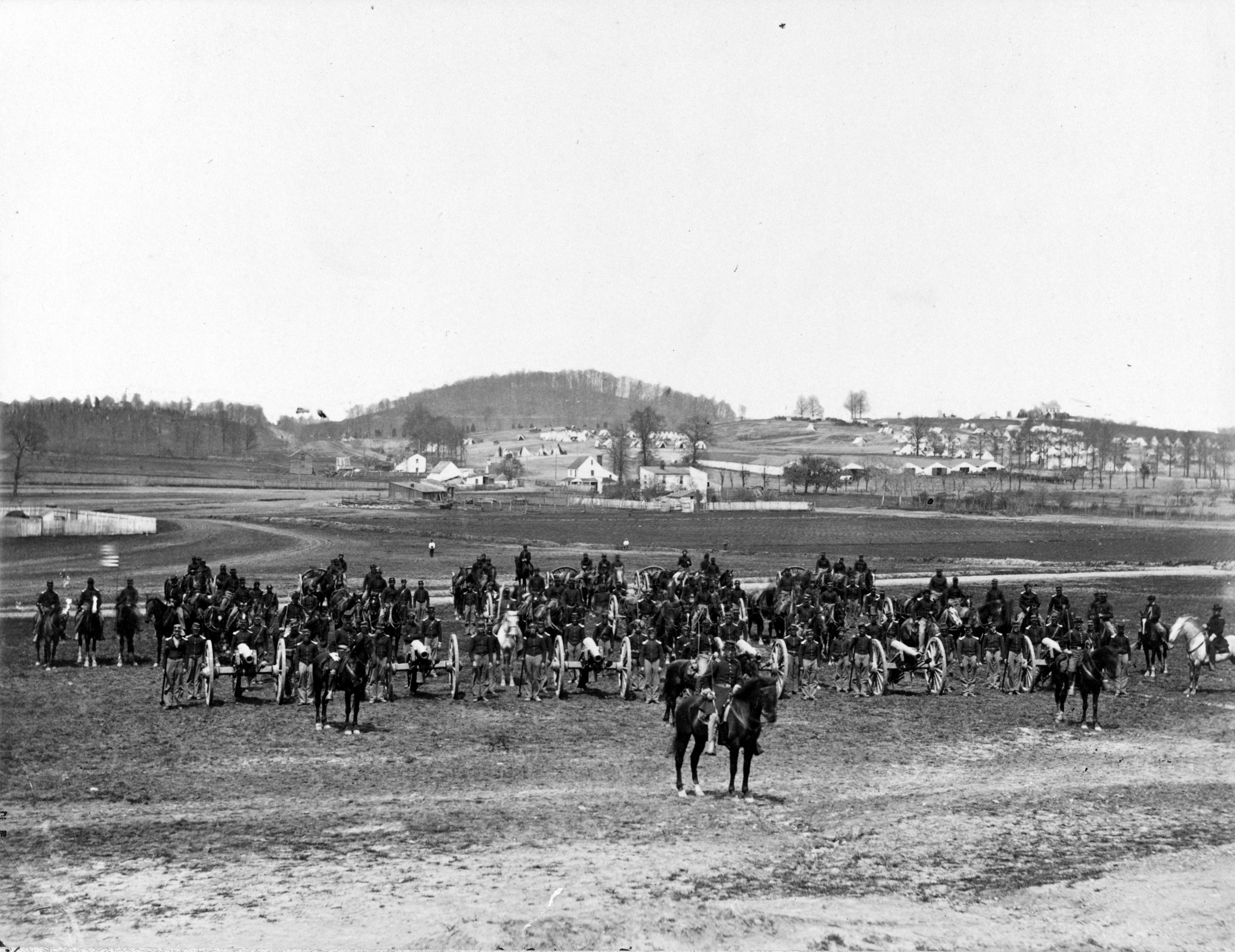

Headquarters 1st New York Light Artillery, Co. L

Camp Barry, Washington D. C.

February 3, 1862

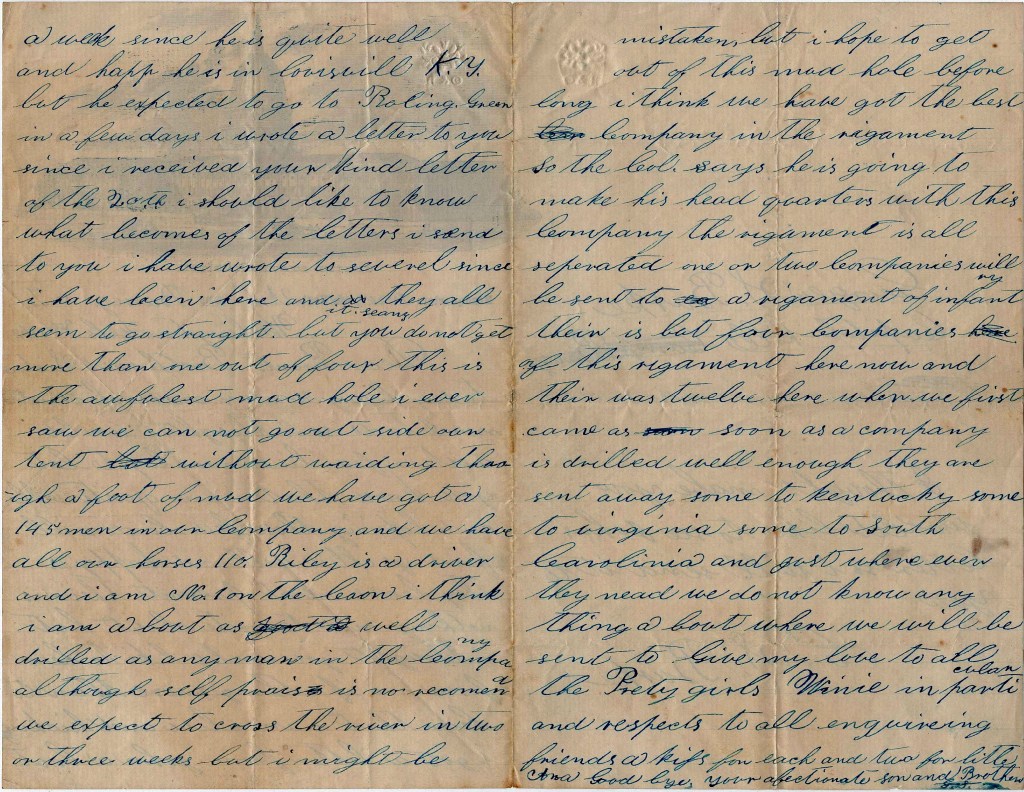

Dear Parents, Brothers and Sisters,

Today being Sunday and I have not much to do, so I thought I would write a few lines mainly to let you know that I am quite well and hoping these few lines will find ye all as well and happy as they leave me at present. There is nothing new to write about but I thought you would like to hear from me if nothing more than to hear that I am alive and kicking.

I got a letter from John about a week since. He is quite well and happy. He is in Louisville, Kentucky, but he expected to go to Bowling Green in a few days. I wrote a letter to you since I received your kind letter of the 20th. I should like o know what becomes of the letters I send to you. I have wrote several since I have been here and they all seem to go straight. But it seems you do not get more than one out of four.

This is the awfullest mud hole I ever saw. We cannot go outside our tent without wading through a foot of mud. We have got 145 men in our company adn we have all our horses, 110. Riley [Benedict] is a driver and I am No. 1 on te cannon. I think I am about as well drilled as any man in the company although self praise os no recommend. We expect to cross the river in two or three weeks but I might be mistaken. But I hope to get out of this mud hole before long. I think we have got the best company in the regiment, so the Colonel says. He is going to make his headquarters with this company.

The regiment is all separated. One or two companies will be sent to a regiment of infantry. There is but four companies of this regiment here now and there was 12 here when we first came. As soon as a company is drilled well enough, they are sent away—some to Kentucky, some to Virginia, some to South Carolina, and just wherever they need. We do not know anything about where we will be sent to.

Give my love to all the pretty girls—Winnie in particular—and respects to all enquiring friends. A kiss for each and two for little Anna. Goodbye. Your affectionate son and brother, — George S. Burke. Capitol Hill

I thought maybe you would like to see John’s letter so I will send it to you. — G. S. Burke

Letter 6

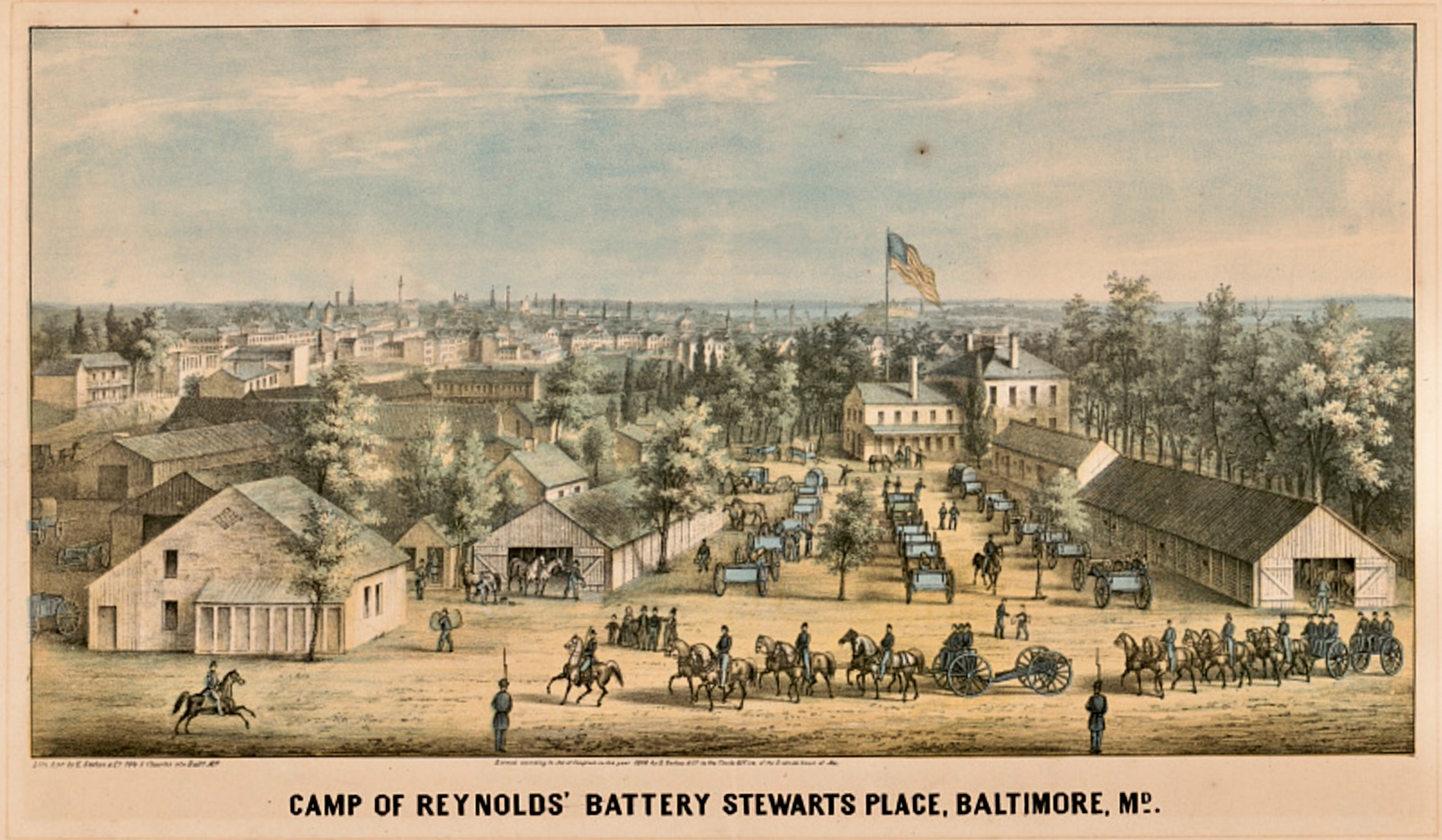

Stewart’s Place

Baltimore, Maryland

May 21, 1862

My dear parents, brothers and sisters,

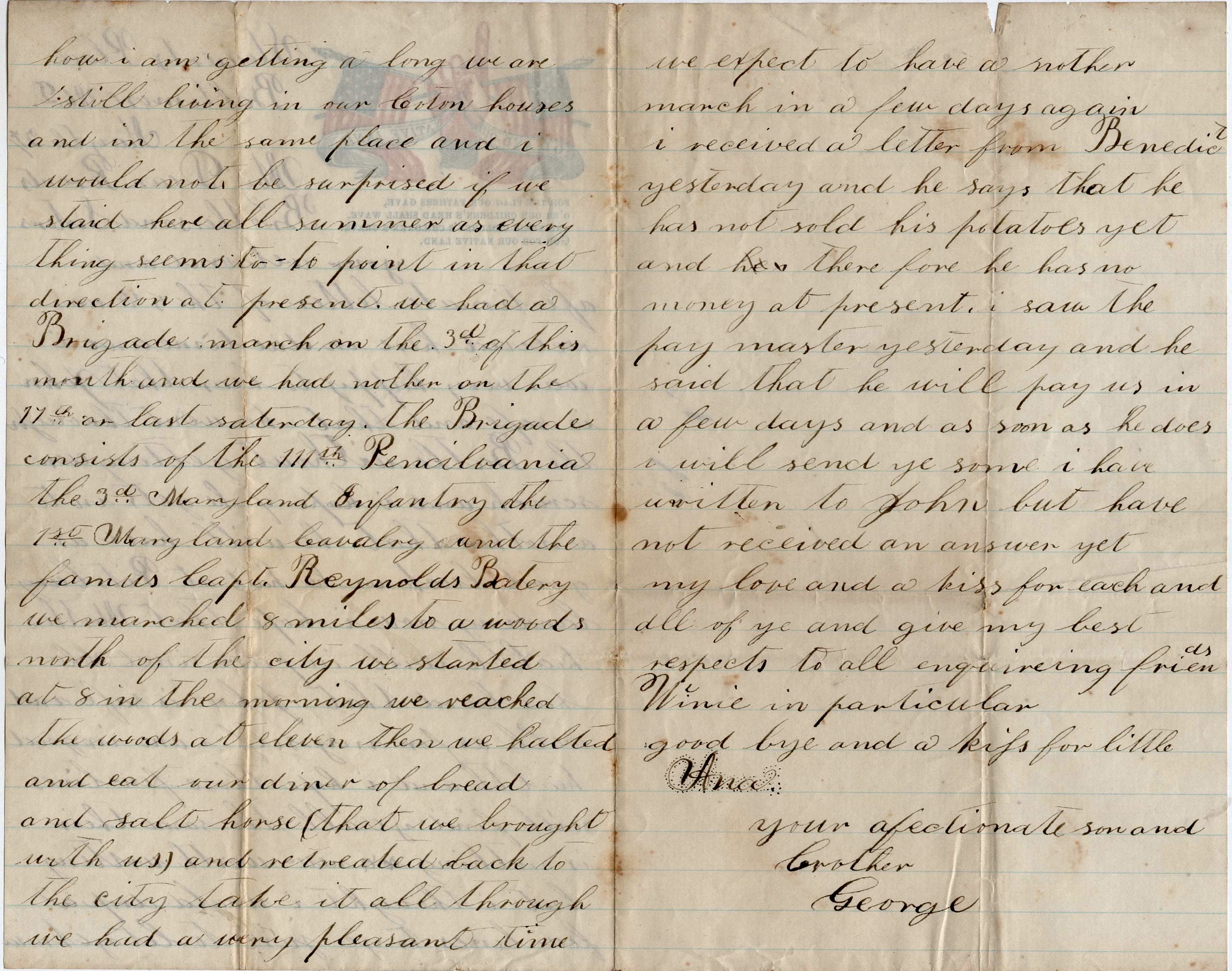

I am in good health and I hope these few lines will find ye all the same. There is nothing new worth writing but I thought I would drop a few lines to ye just to let ye know how I am getting along.

We are still living in our cotton houses and in the same place and I would not be surprised if we stayed here all summer as everything seems to point in that direction at present. We had a Brigade march on the 3rd of this month and we had another on the 17th or last Saturday. The Brigade consists of the 111th Pennsylvania, the 3rd Maryland Infantry, the 1st Maryland Cavalry, and the famous Capt. Reynolds’ Battery. We marched 8 miles to a woods north of the city. We started at 8 in the morning. We reached the woods at eleven. Then we halted and eat our dinner of bread and salt horse (that e brought with us) and retreated back to the city. Take it all through, we had a very pleasant time.

Your welcome and affectionate letter of the 5th was received here is due time adn I was very happy to hear that John is safe and that he went through the battle without getting even a scratch. And I hope he will have as good luck as he had at Pittsburg Landing now. I hope that Mother’s health will improve since she has heard that John is safe.

We expect to have another march in a few days again. I received a letter from Benedict yesterday and he says that he has not sold his potatoes yet and therefore he has no money at present. I saw the pay master yesterday and he said that he will pay us in a few days and as soon as he does, I will send ye some.

I have written to John but have not received any answer yet. My love and a kiss for each and all of ye, and give my best respects to all enquiring friends—Winnie in particular. Goodbye and a kiss for little Anna. Your affectionate son and brother, — George

Letter 7

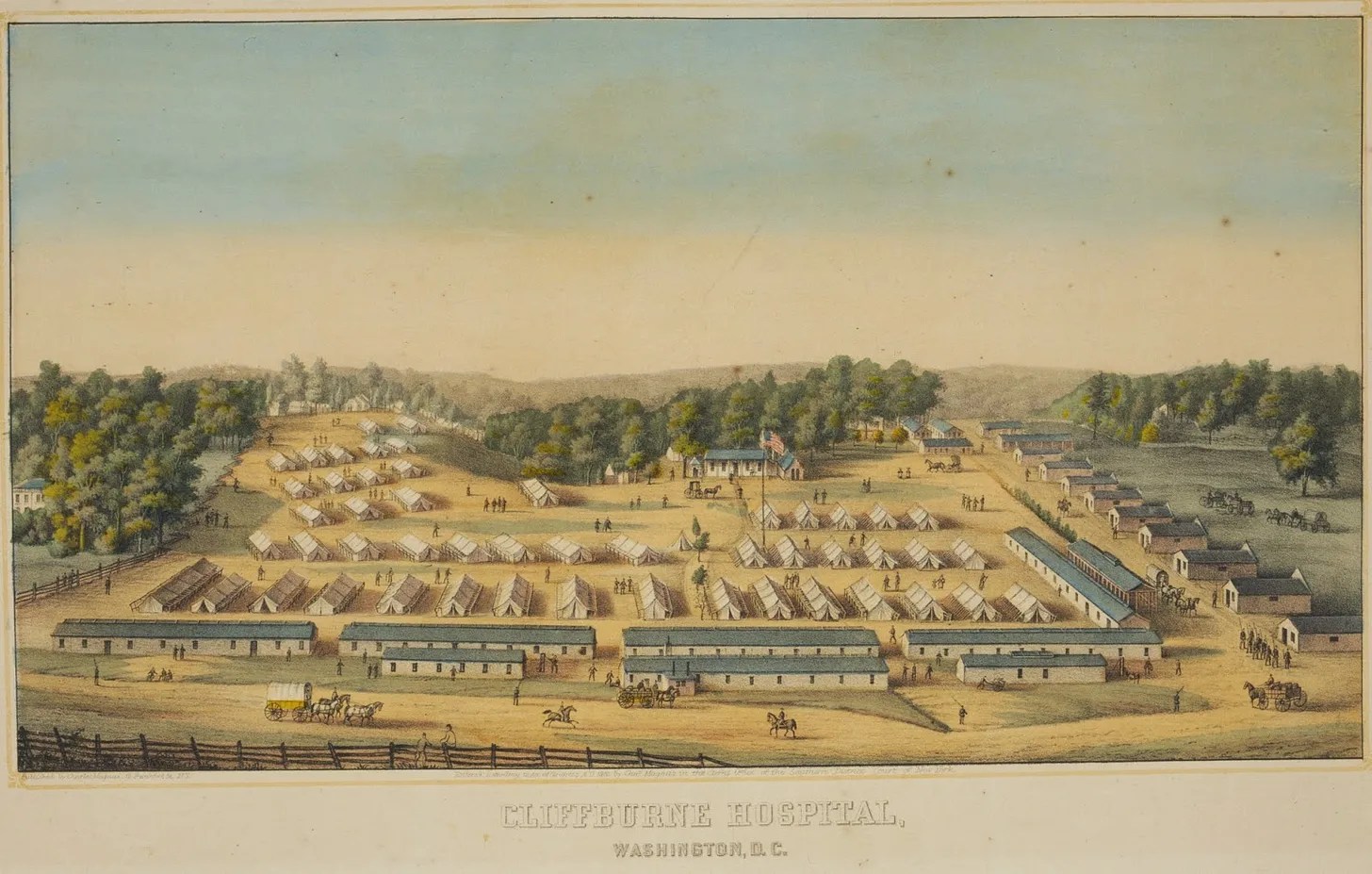

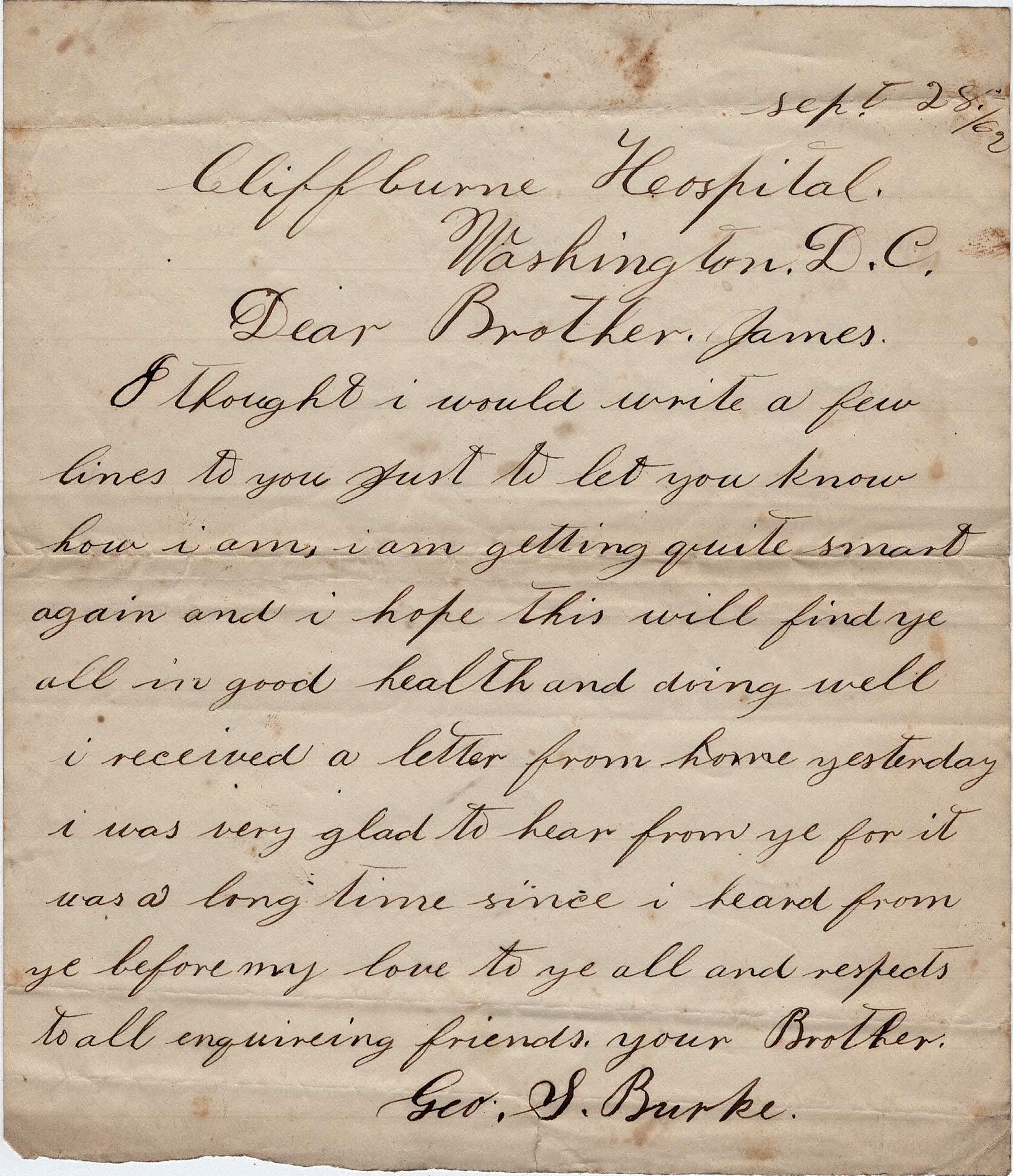

Cliffburne Hospital

Washington D. C.

September 28, 1862

Dear Brother James,

I thought I would write a few lines to you just to let you know hoe I am. I am getting quite smart again and I hope his will find ye al in good health and doing well. I received a letter from home yesterday. I was very glad to hear from ye for it was a long time since I heard from ye before.

My love to ye all and respects to all enquiring friends. Your Brother, — George S., Burke

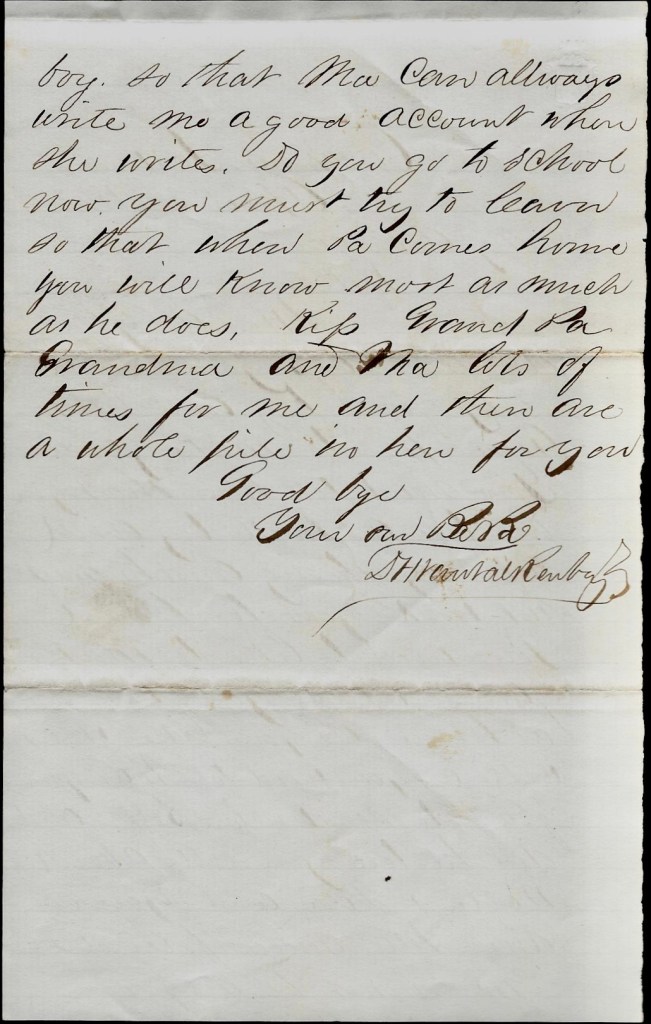

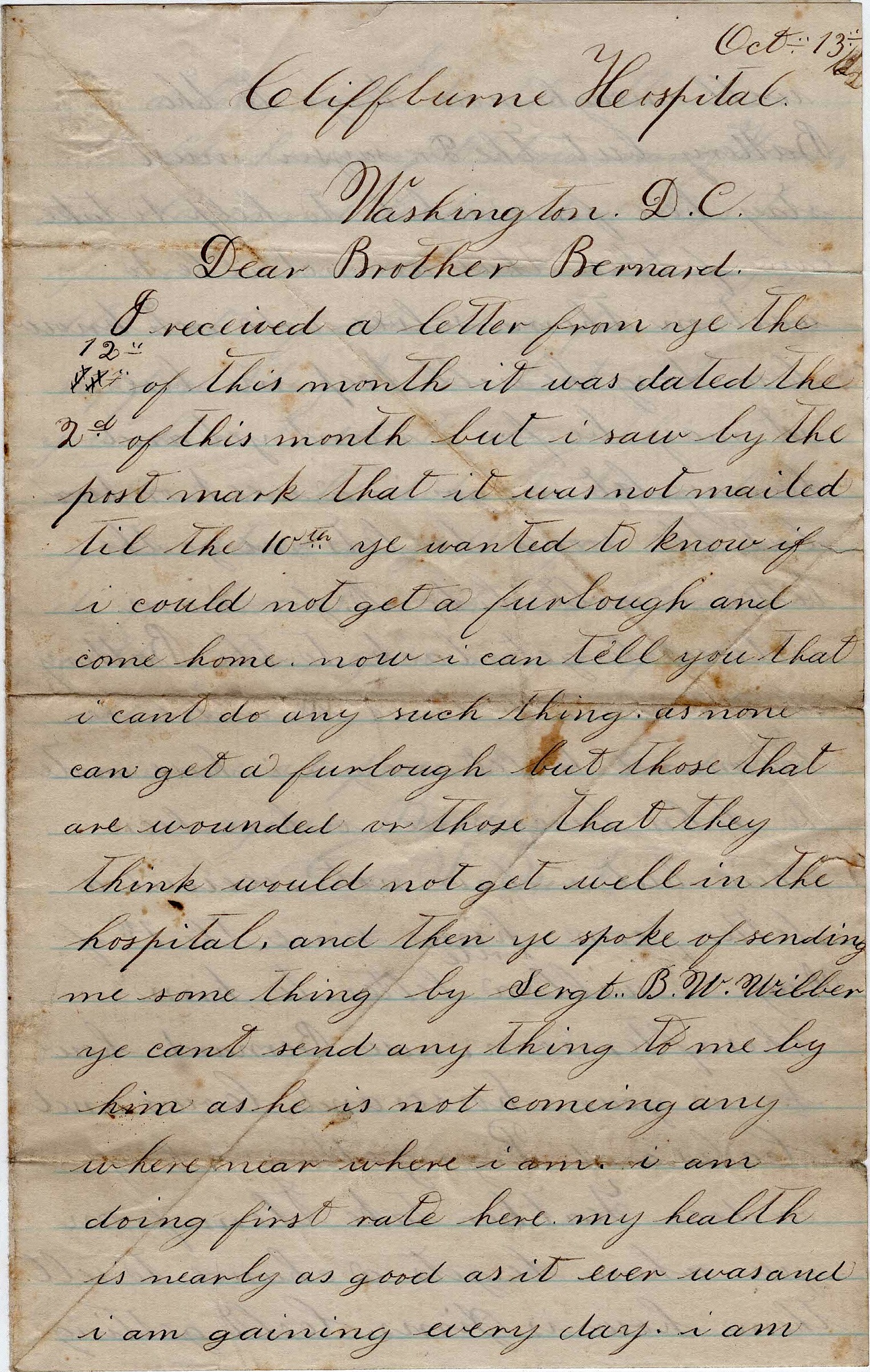

Letter 8

Cliffburne Hospital

Washington D. C.

October 15, 1862

Dear Brother Bernard,

I received a letter from ye the 12th of this month. It was dated the 2d of this month but I saw by the postmark that it was not mailed till the 10th. Ye wanted to know if I could not get a furlough and come home. Now I can tell you that I can’t do any such thing as none can get a furlough but those that are wounded or those they think would not get well in the hospital. And then ye spoke of sending me something by Sgt. B. W. Wilber. Ye can’t send anything to me by him as he is not coming anywhere near where I am.

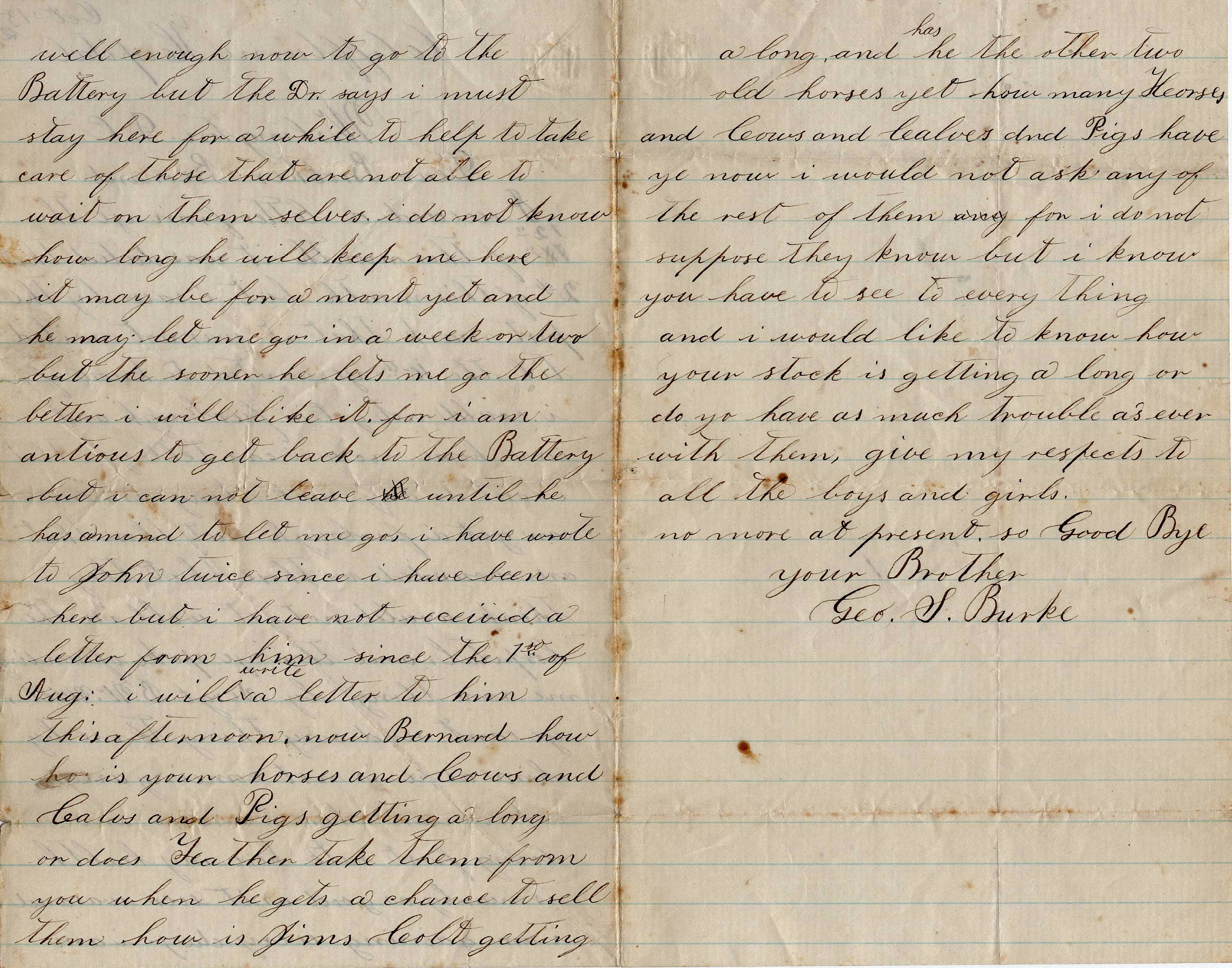

I am doing first rate here. My health is nearly as good as it ever was and well enough now to go to the Battery but the doctor says I must stay here for a while to help to take care of those that are not able to wait on themselves. I do not know how long he will keep me here. It may be for a month yet and he may let me go in a week or two. But the sooner he lets me go, the better I will like it for I am anxious to get back to the Battery. But I cannot leave until he has a mind to let me go.

I have wrote to John twice since I have been here but I have not received a letter from him since the 1st of August. I will write a letter to him this afternoon.

Now Bernard, how is your horses and cows and calves and pigs getting along? Or does Father take them from you when he gets a chance to sell them? How is Jim’s colt getting along? And has he the other two old horses yet? How many horses and cows and calves and pigs have ye now? I would not ask any of the rest of them for I do not suppose they know but I know you have to see to everything and I would like to know how your stock is getting along or do you have as much trouble as ever with them?

Give my respects to all the boys and girls. No more at present. So goodbye. Your brother, — George S. Burke

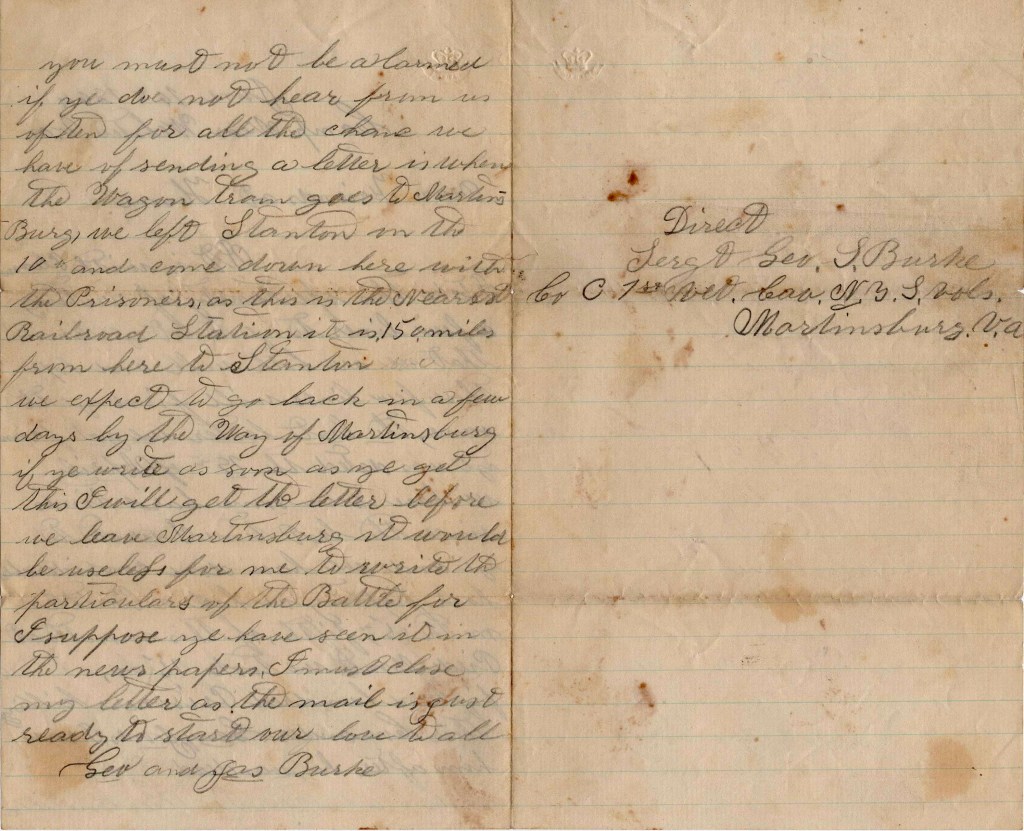

Letter 9

[Editor’s Note: George wrote this letter while serving in the 1st New York Veteran Cavalry]

Camp near Winchester, Virginia

June 16, 1864

Dear Friends at home,

It is with pleasure I take this opportunity of writing a few lines to ye to let ye know that we are both well and hope these few lines will find ye the same. The last letter we got from ye was dated the 19th of April. We have seen some hard times since the last time I wrote to ye and we have done considerable hard fighting. We had a battle on the 5th of this month at Piedmont. We took 1500 prisoners, killing their commander, Gen. [Grumble] Jones. I saw him after he was dead. [see Battle of Piedmont]

You must not be alarmed if ye do not hear from us often for all the chance we have of sending a letter is when the wagon train goes to Martinsburg. We left Staunton on the 10th and came down here with the prisoners as this is the nearest railroad station. It is 150 miles from here to Staunton. We expect to go back in a few days by the way of Martinsburg. If ye write as soon as ye get this, I will get the letter before we leave Martinsburg. It would be useless for me to write the particulars of the battle for I suppose ye have seen it in the newspapers.

I must close my letter as the mail is just ready to start. Our love to all, — George and James Burke

Direct to George S. Burke. Co. C, 1st Veteran Cavalry N. Y. Vols., Martinsburg, Va.

Letter 10

Camp Piatt, [15 miles. south of Charleston] West Virginia

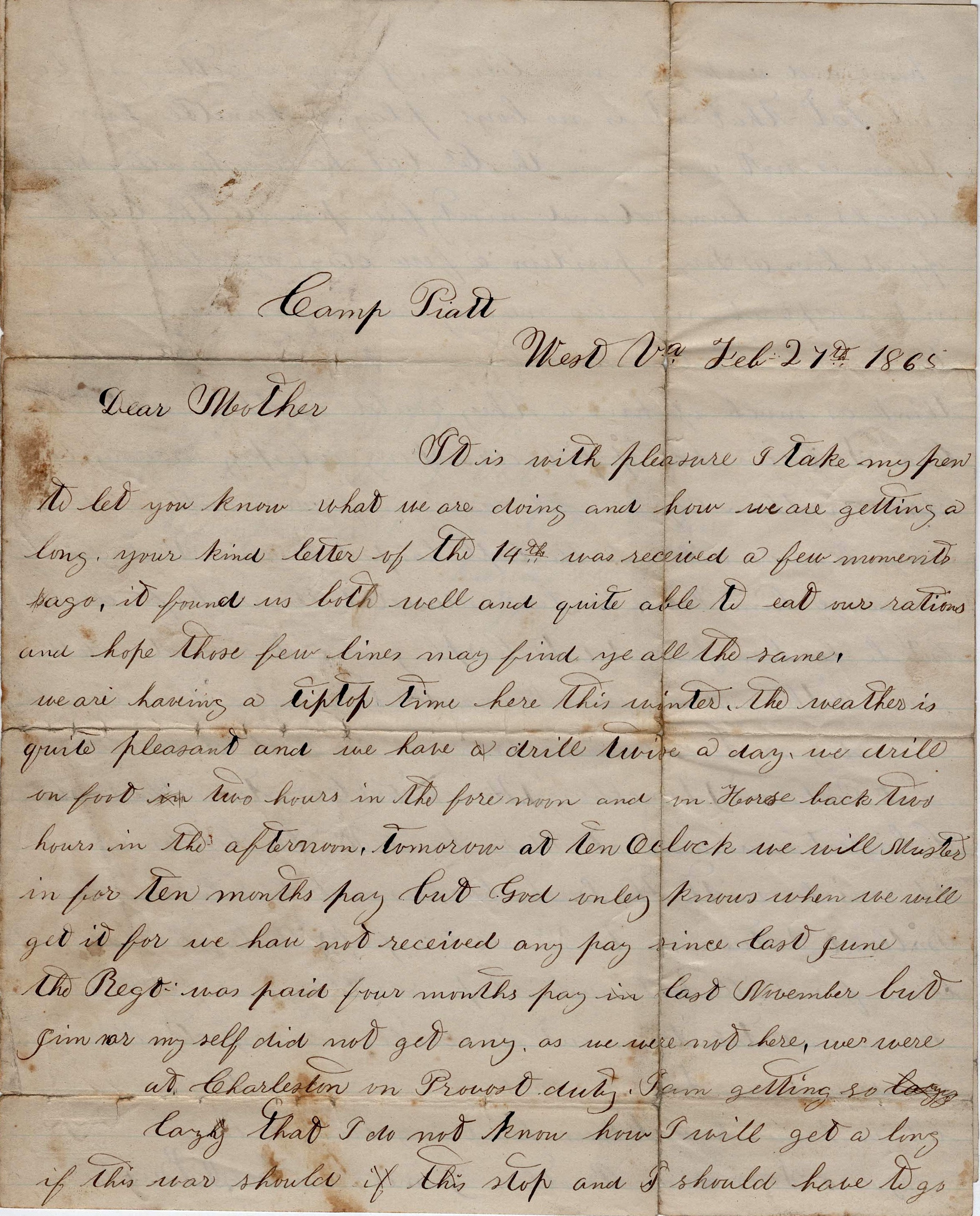

February 27, 1865

Dear Mother,

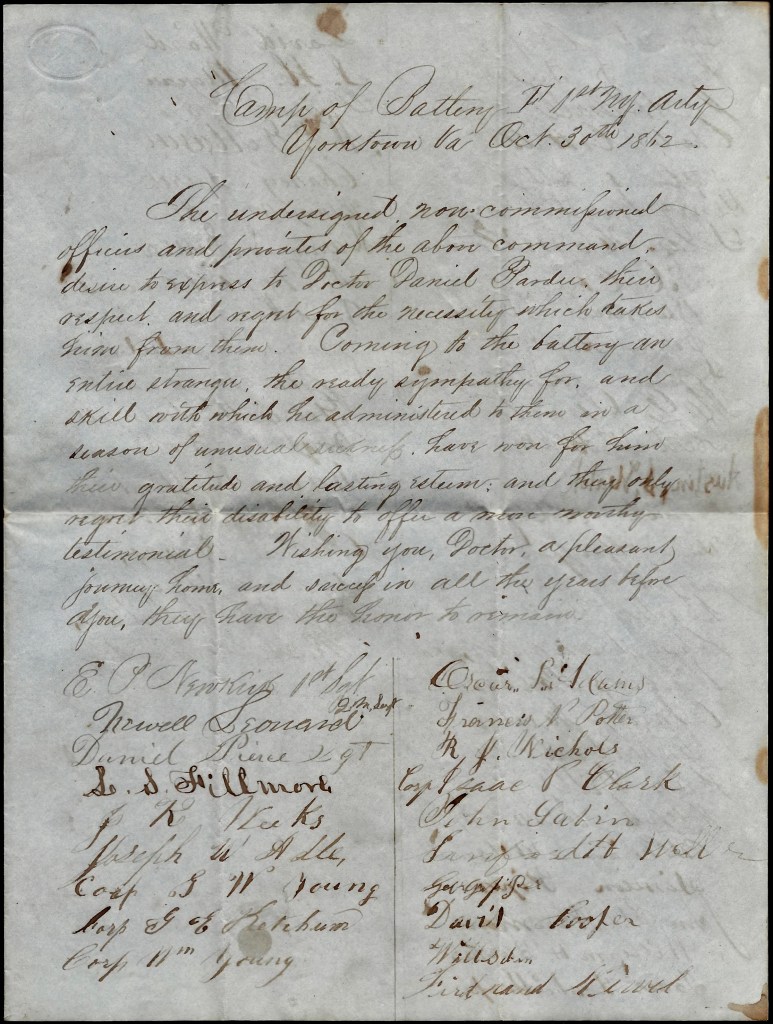

Itis with pleasure I take my pen to let you know what we are doing and how we are getting along. Your kind letter of the 14th was received a few minutes ago. It found us both well and quite able to eat our rations and hope these few lines may find ye all the same.

We are having a tip top time here this winter. The weather is quite pleasant and we have a drill twice a day. We drill on foot two hours in the forenoon and on horseback two hours in the afternoon. Tomorrow at 10 o’clock we will muster in for ten months pay but God only knows when we will get it for we have not received any pay since last June. The regiment was paid four months pay in last November but Jim nor myself did not get any as we were not here. We were at Charleston on Provost Duty. I am getting so lazy that I do not know how I will get along if this war should stop and I should have to go home and work for my living.

Jim is getting so big and fat that it is no boys play to handle him. There is not a man in the company but he can handle. He weighs 195 pounds. The Captain offered him a sergeant’s position a few days ago but he would not accept it nor give me any reason for doing so. The boys all tried to have him accept it for they all think as much of him as they could of their own brother.

Con. Sullivan has stopped drinking whiskey or anything stronger than coffee in four months and says he never will and the Captain has put him in [as] sergeant to encourage him. Hatch has been reduced to the ranks for drunkenness but he has been promoted to corporal.

Jim just received a letter from Mother and one from Barnard. He is going to answer them in a day or two. We have been in one battle at New Market, one at Piedmont, at Lynchburg, at Winchester, at Kernstown, at Martinsburg, at Charleston, and at Maryland Heights, besides several skirmishes with the bushwhackers and guerrillas and one Battle of Leetown on the 3rd and 4th of July.

The bugles have just blown for drill so I must stop scribbling and fall the company in and take them out to drill. Our respects to all enquiring friends and our love to each of ye. Write soon and let us know how Father’s hand is getting along. Your sons and brothers, — James and George S. Burke