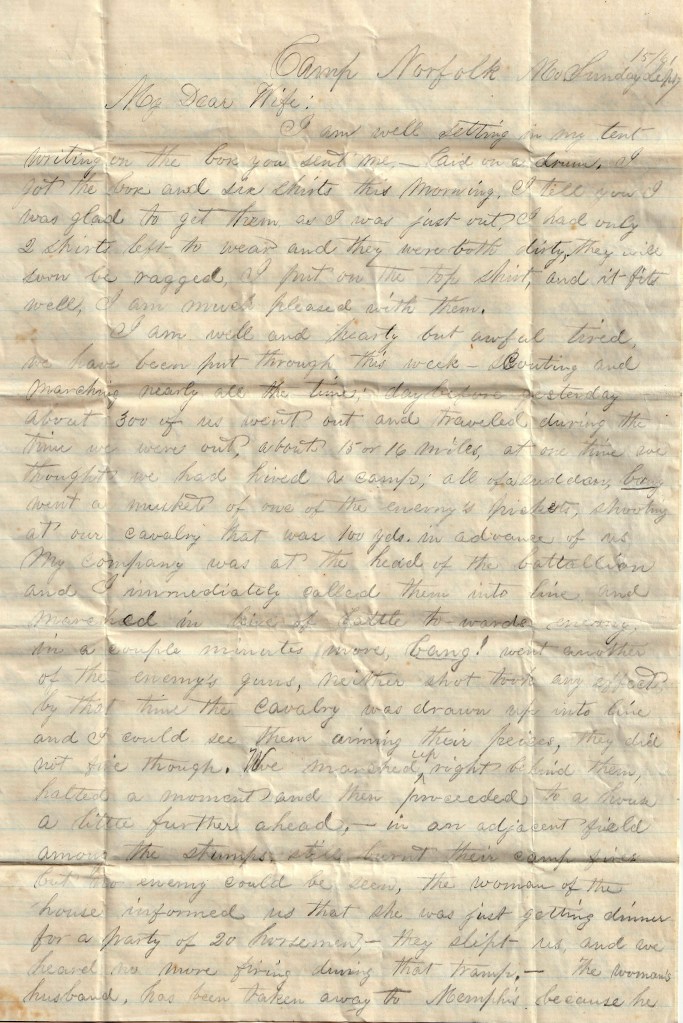

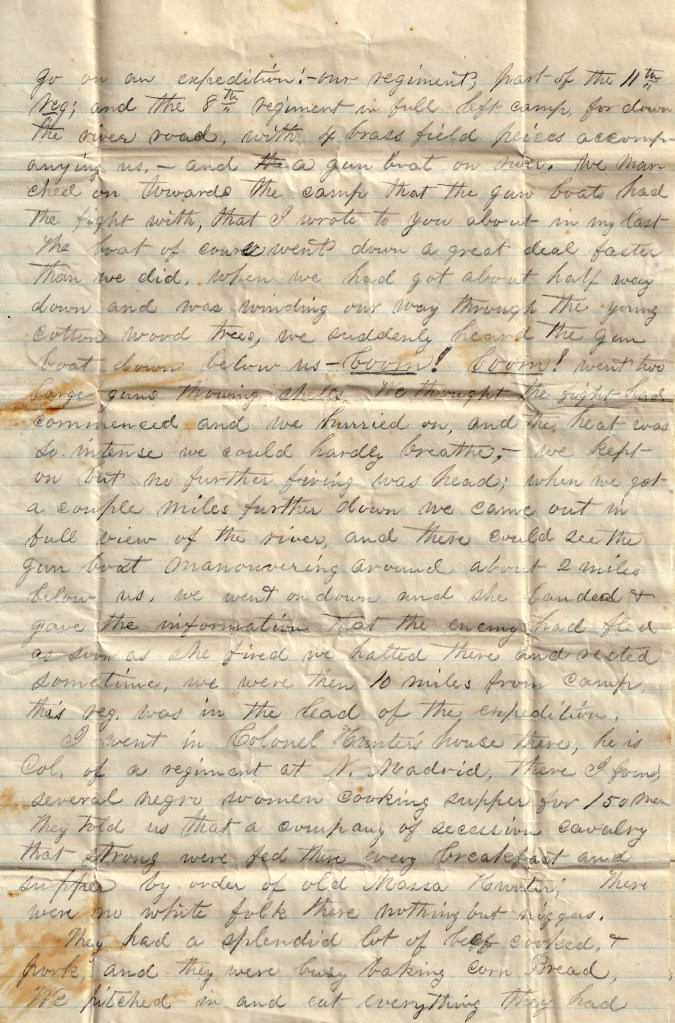

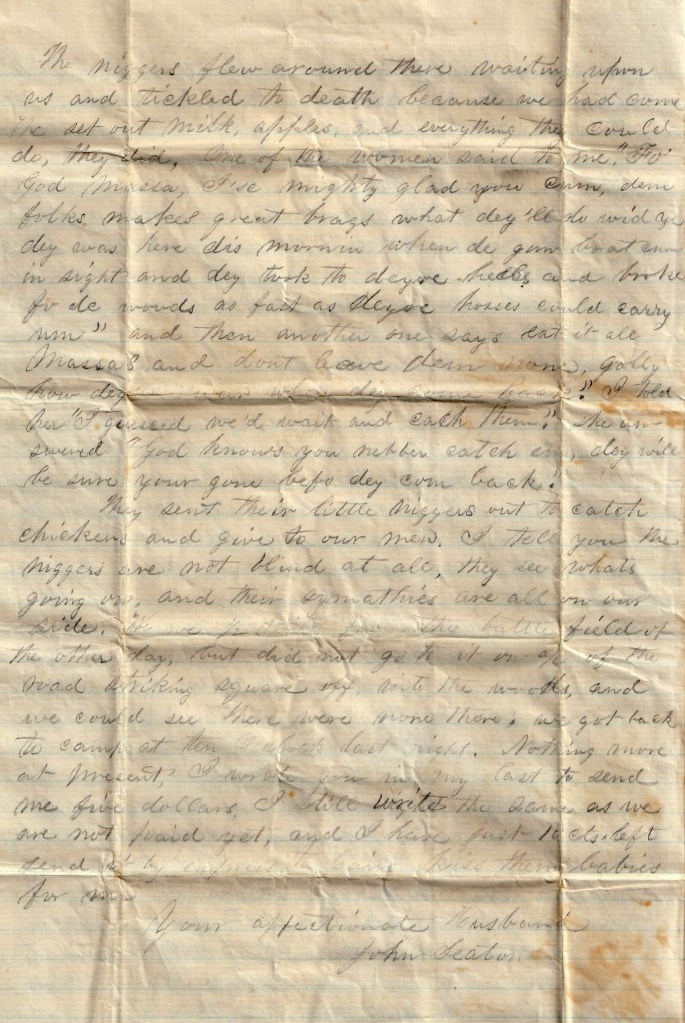

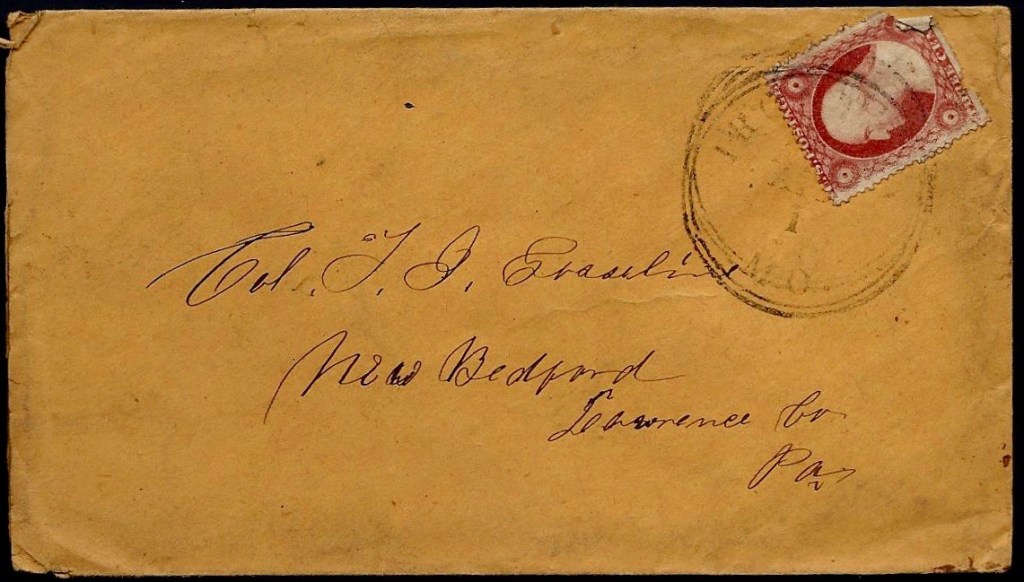

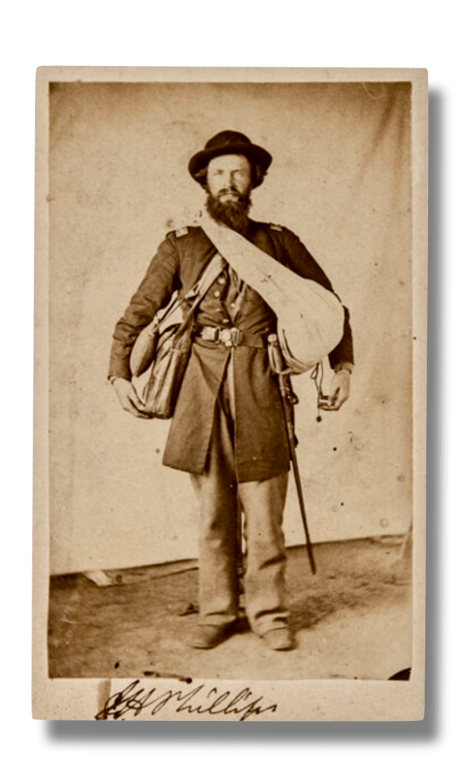

This letter was written by John Howell Phillips (1832-1876) from the camp of the 22nd Illinois Infantry in March 1864 while serving as Captain of Co. D. There were 27 of his letters ranging in date from January 8, 1862 to May 24, 1865 sold at auction in 2015. It isn’t clear if this was one of them or not. They were all written to his mother or sister Alice (“Allie”). They were datelined from Corinth, Camp Lyon, Florence [Alabama], Nashville, Murfreesboro, Stone River, Bayou Pierre [Mississippi], Bridgeport [Alabama], Cairo [Illinois] and others.

In one of the letters he wrote, “The inspector on General Grant’s staff is to inspect us and I think he will find a ragged and dirty set as the regiment has been out on the tramp nearly all winter and have not had a chance of keeping themselves in any kind of decency… You have no doubt seen a great deal in the newspapers about the Rebels being nearly starved out and that they are deserting because they did not get enough to eat. But if they fare any worse than we men in this Department have this winter I pity the poor devils.”

John was born in Connellsville, Fayette county, Pennsylvania. He was the son of John Wesley Phillips (1803-1867) and Margaret Rice Connell (1808-1895). When John enlisted in June 1861, he gave his occupation as carpenter and his residence as Greenville, Bond county, Illinois. He was described as standing just over 5′ 9″ tall, with light hair and blue eyes. He claimed to be single but he was, more accurately, a widower. His wife, Mary Virginia Buie (1833-1859) died on 22 June 1859 after less than two years of marriage.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

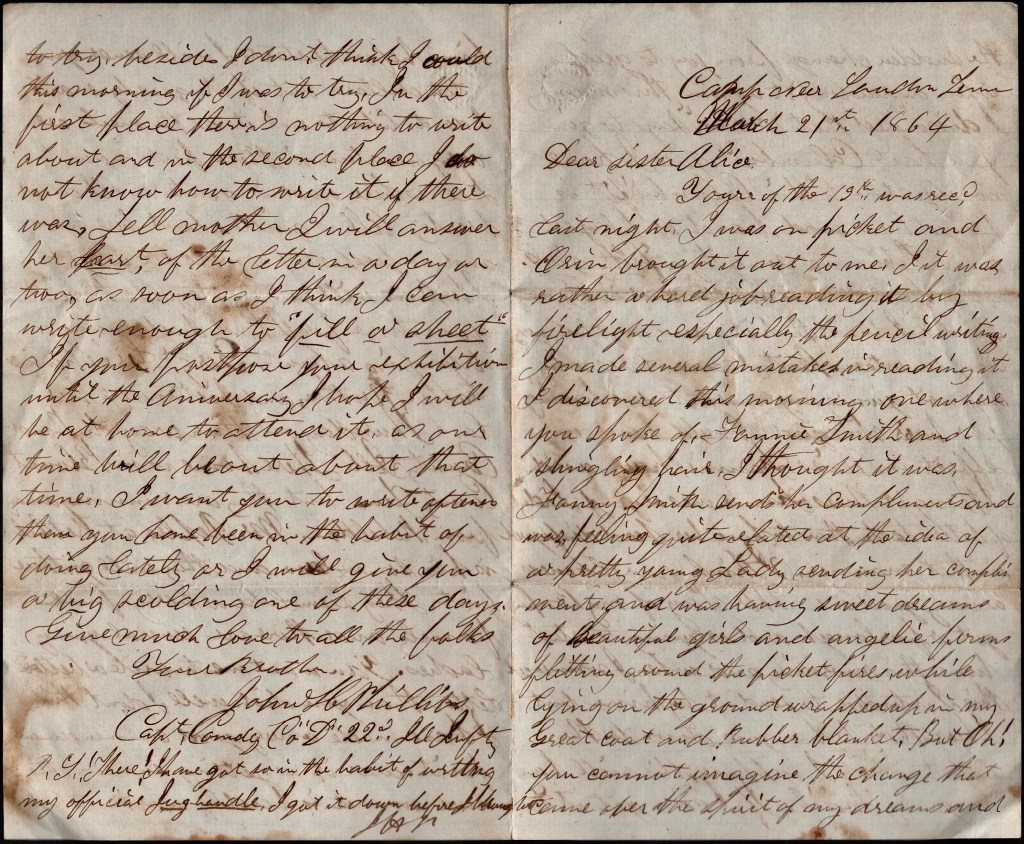

Camp near Louden, Tennessee

March 21st 1864

Dear sister Alice,

Yours of the 13th was received last night. I was on picket and Orin brought it out to me. It was rather a hard job reading it by firelight—especially the pencil writing. I made several mistakes in reading it. I discovered this morning one where you spoke of Fannie Smith and shingling hair. I thought it was Fanny Smith sends her compliments and was feeling quite elated at the idea of a pretty young lady sending her compliments and was having sweet dreams of beautiful girls and angelic forms flitting around the picket fires while lying on the ground wrapped in my great coat and rubber blanket.

But oh!! you cannot imagine the change to come over the spirit of my dreams and the sudden change from joy to grief when on reading it again this morning I discovered that it was, “says to give you Hail Columbia.” Now I have no objection to “Hail Columbia” if it is played by a good band or played on a piano and sung by a pretty girl. but when it comes in a letter and in the way this did, I do not think it means anything very complimentary. But I cannot see why my not giving my consent to you having your hair shingled should have any effect on Miss Fannie’s hair, and I thought Miss Fannie was a young lady of better taste than to have her head disfigured in that manner.

I think your likeness a very good one. Mr. [Joseph A.] Jay of my company got a furlough and is going to start home this morning and when I commenced this I intended to send it by him but I hear that he has gone down to the Depot and I suppose this will have to go by mail. If I can get it to him before he starts, I will send you ten dollars but if it goes by mail, I don’t like to risk it as the mails are very uncertain in these parts now.

Lee is here and is quite well and hearty. All is quiet about here now and no prospect of a move for us yet. I hope we will get to stay here the rest of our time for I have had enough tramping about. Sergt. [Archibald C.] Grisham’s father, mother, and sisters were here last Thursday on their way to Bond County, Illinois. Their home is in Blount county, Tennessee, but they are running away from Rebeldom. Mr. Peoples at Bethel is his son-in-law and they will go there first. They seem like a very fine family and there are several young ladies.

You want me to write a better letter than you did. Well, I don’t. think I have made a very good commencement for it and it is getting so near the end now it is hardly worthwhile to try. Beside, I don’t think I could this morning if I was to try. In the first place, there is nothing to write about. And in the second place, I do not know how to write it if there was. Tell mother I will answer her part of the letter in a day or two, as soon as I think I can write enough to “fill a sheet.”

If you postpone your exhibition until the Anniversary, I hope I will be at home to attend it, as our time will be out about that time. I want you to write oftener than you have been in the habit of doing lately or I will. give you a big scoulding one of these days. Give much love to all. the folks. Your brother, — John H. Phillips, Captain Commanding Co. D, 22nd Illinois Infantry.

P. S. There! I have got so in the habit of writing my official jug handle, I got it down before I thought. — J. H. P.