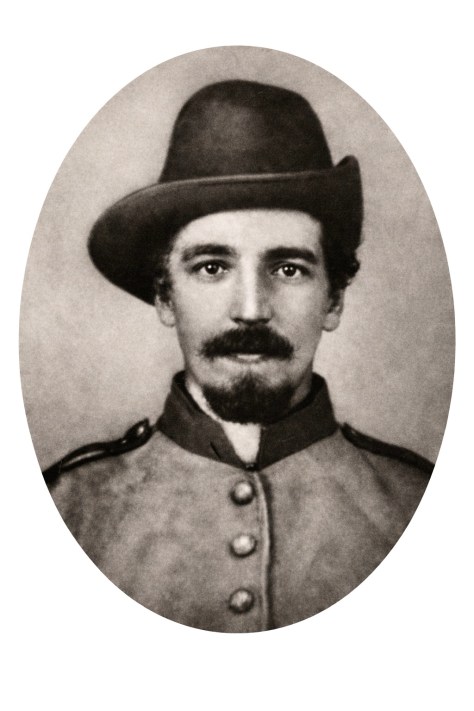

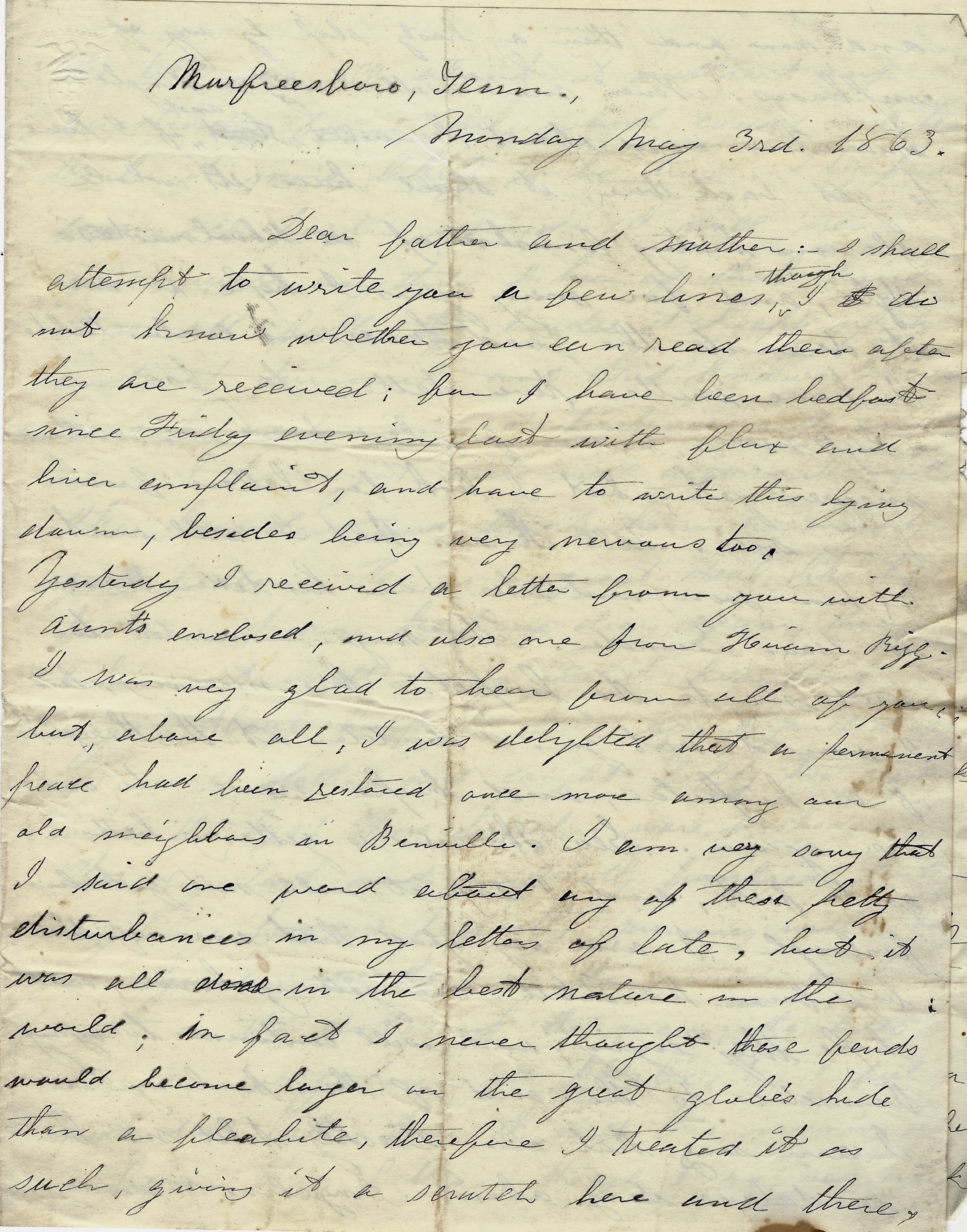

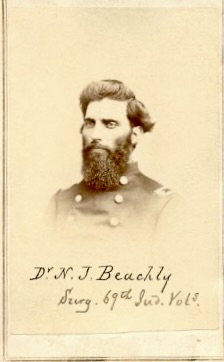

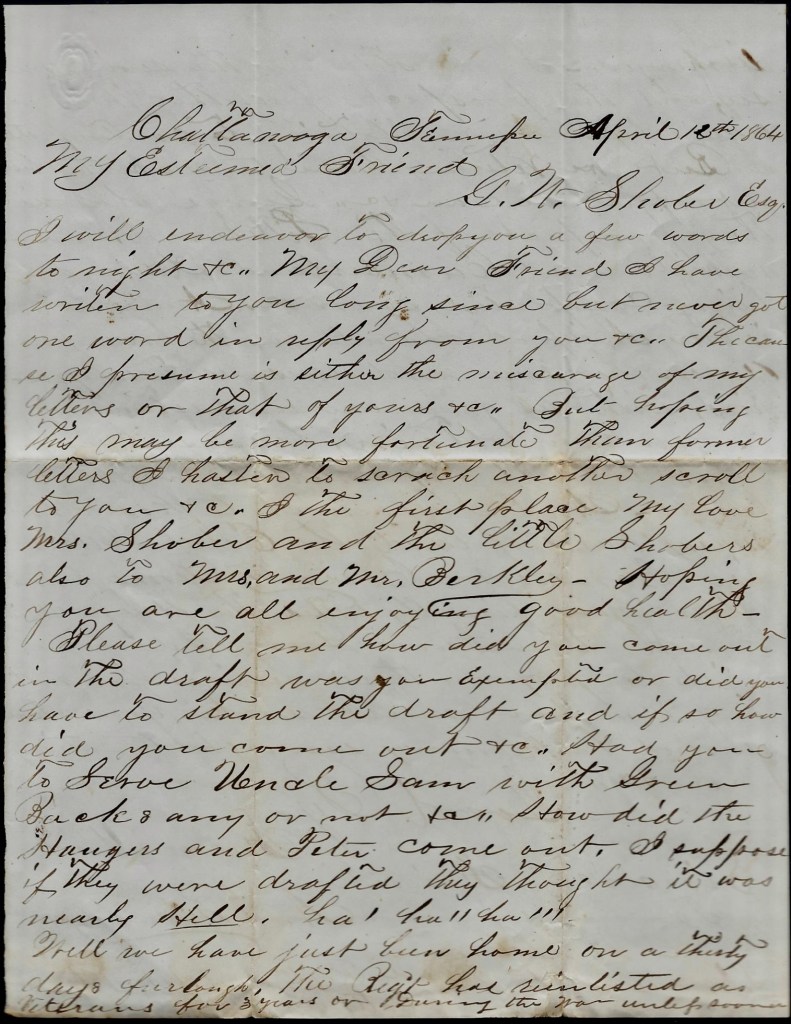

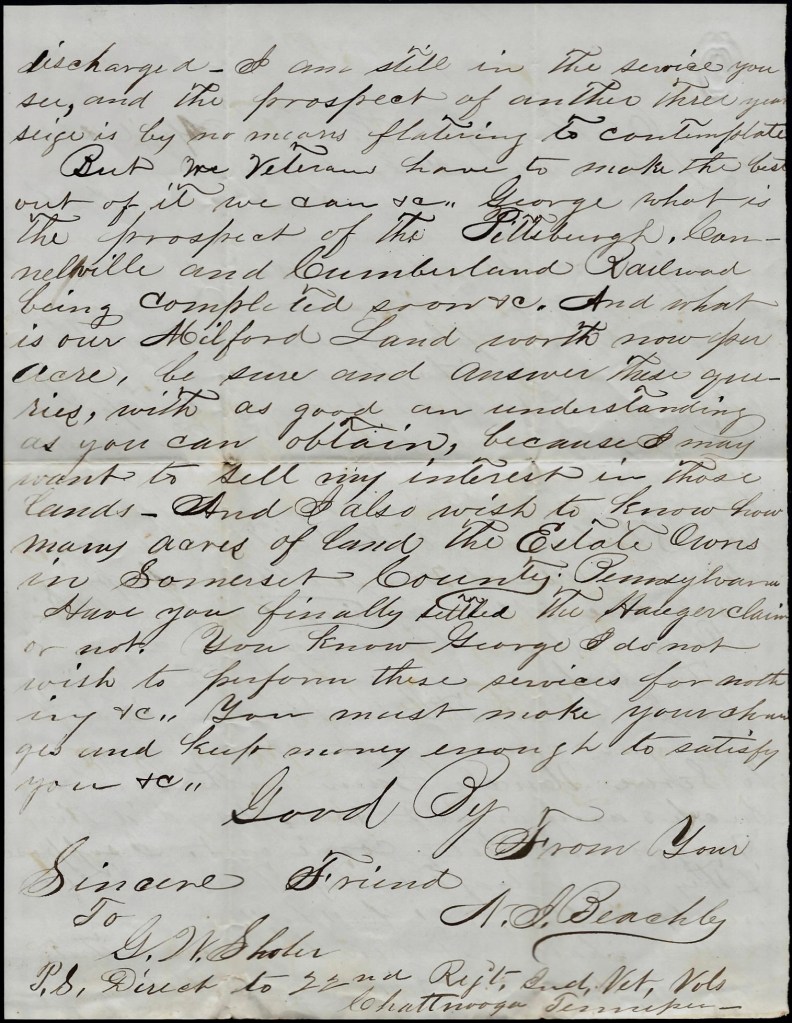

This diary fragment was written by James Andrew Guirl (1841-1868), the son of Isaac Guirl (1813-1879) and Jane Redick (1813-1888) of Benville, Jennings county, Indiana. In the 1860 US Census, James was enumerated in his parent’s home as a 19 year-old portrait painter. Just prior to his enlistment, James moved to San Jacinto in Jennings county, and while there offered his services in Capt. Michael Gooding’s Co. A of the 22nd Indiana Volunteers in July 1861. He later transferred to Captain David Dailey’s Co. D. Throughout his time in the service, James suffered ill health and a game leg. He was eventually discharged for disability in August 1863. After the war, he moved to Franklin, Venango county, Pennsylvania to visit an uncle and work in the oil fields but again his health failed and her returned to Indiana where he died in 1868.

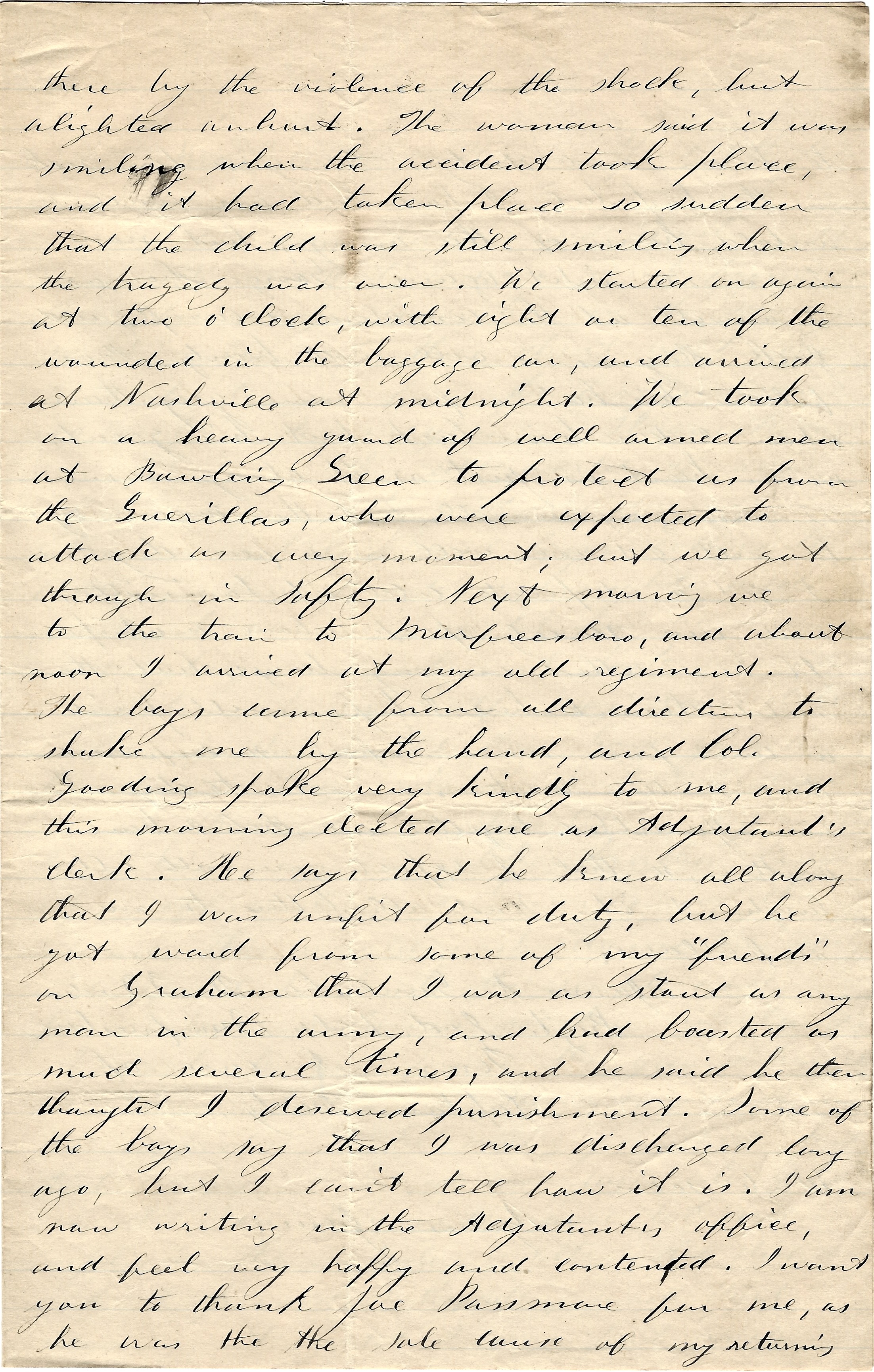

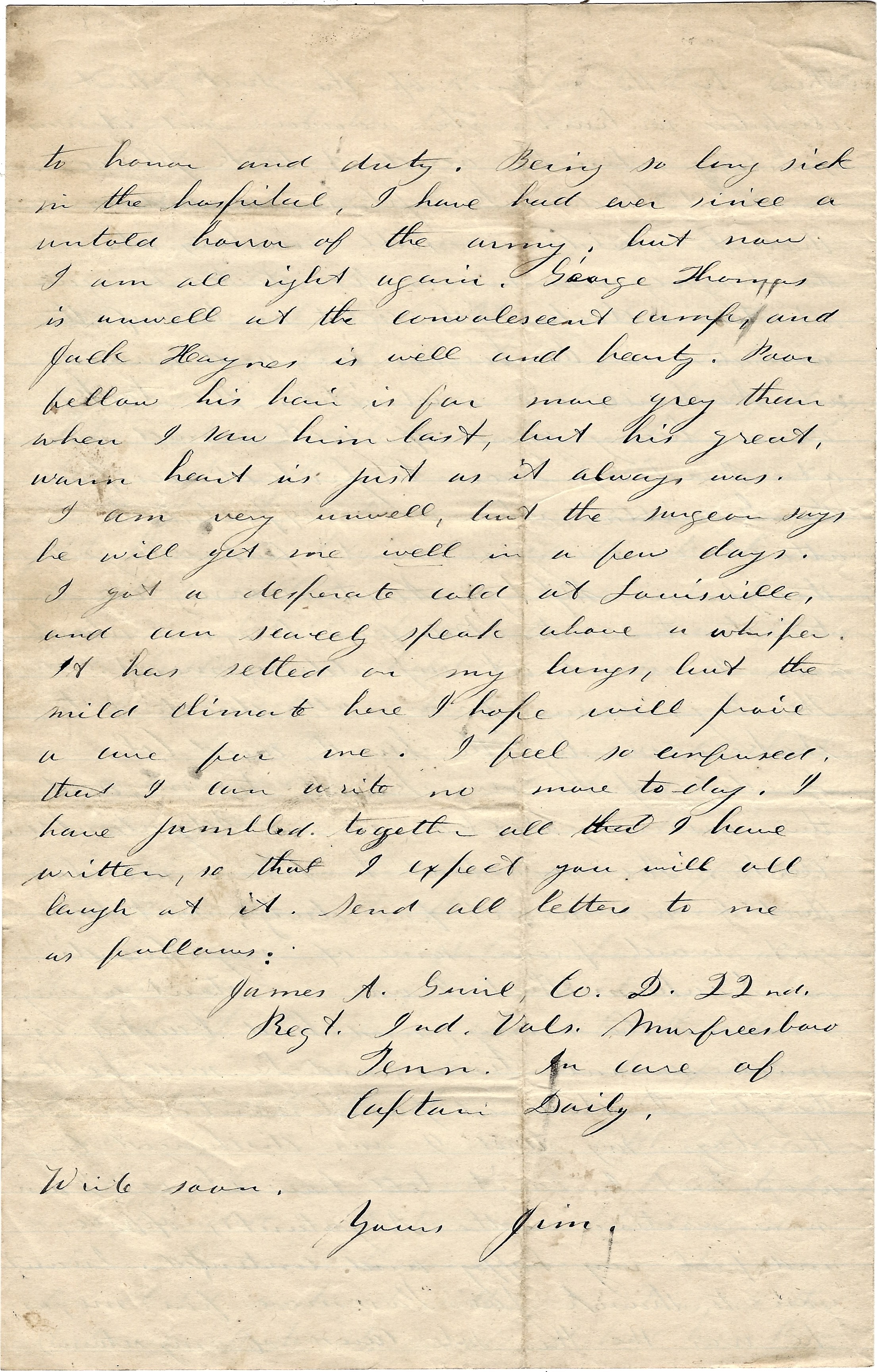

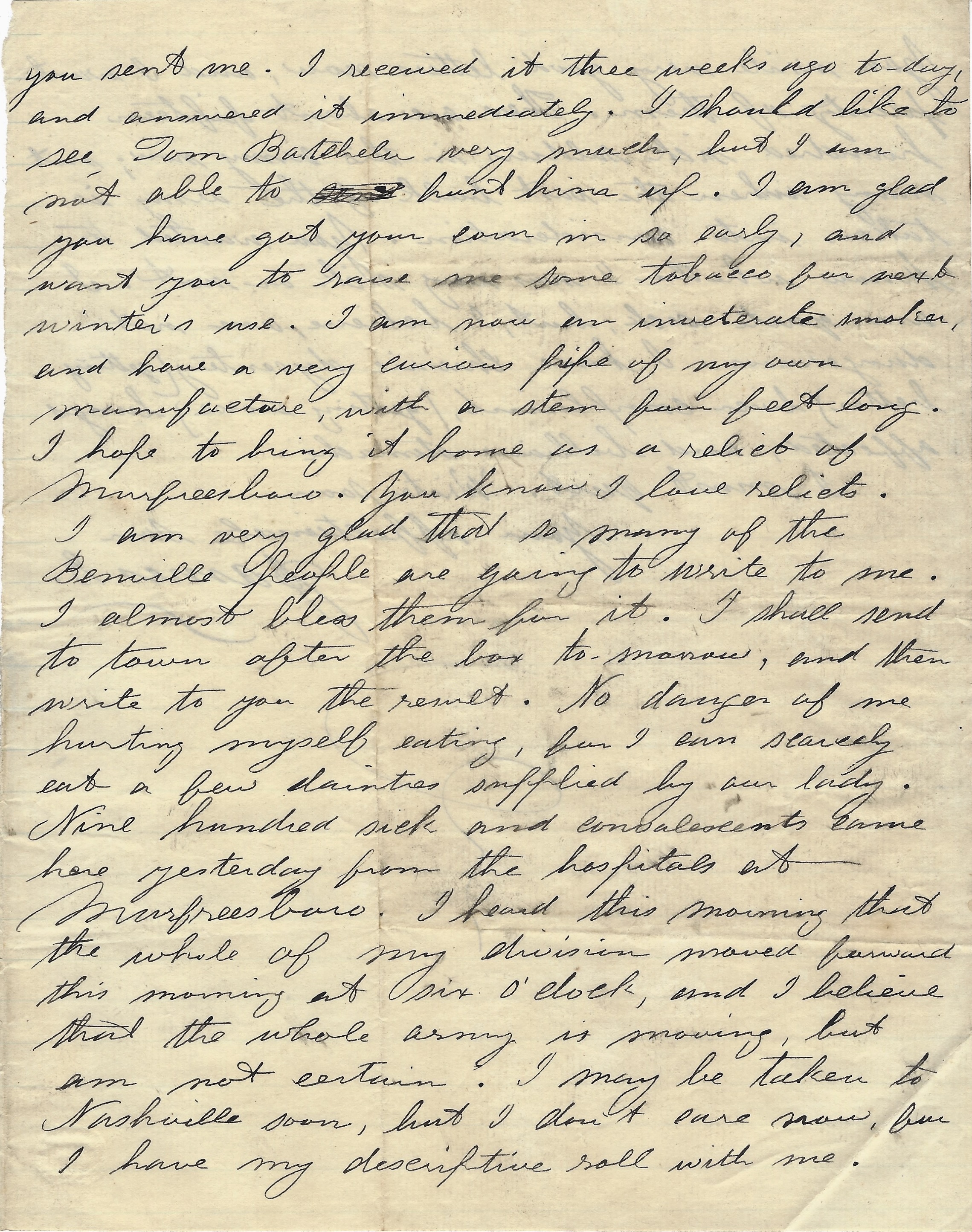

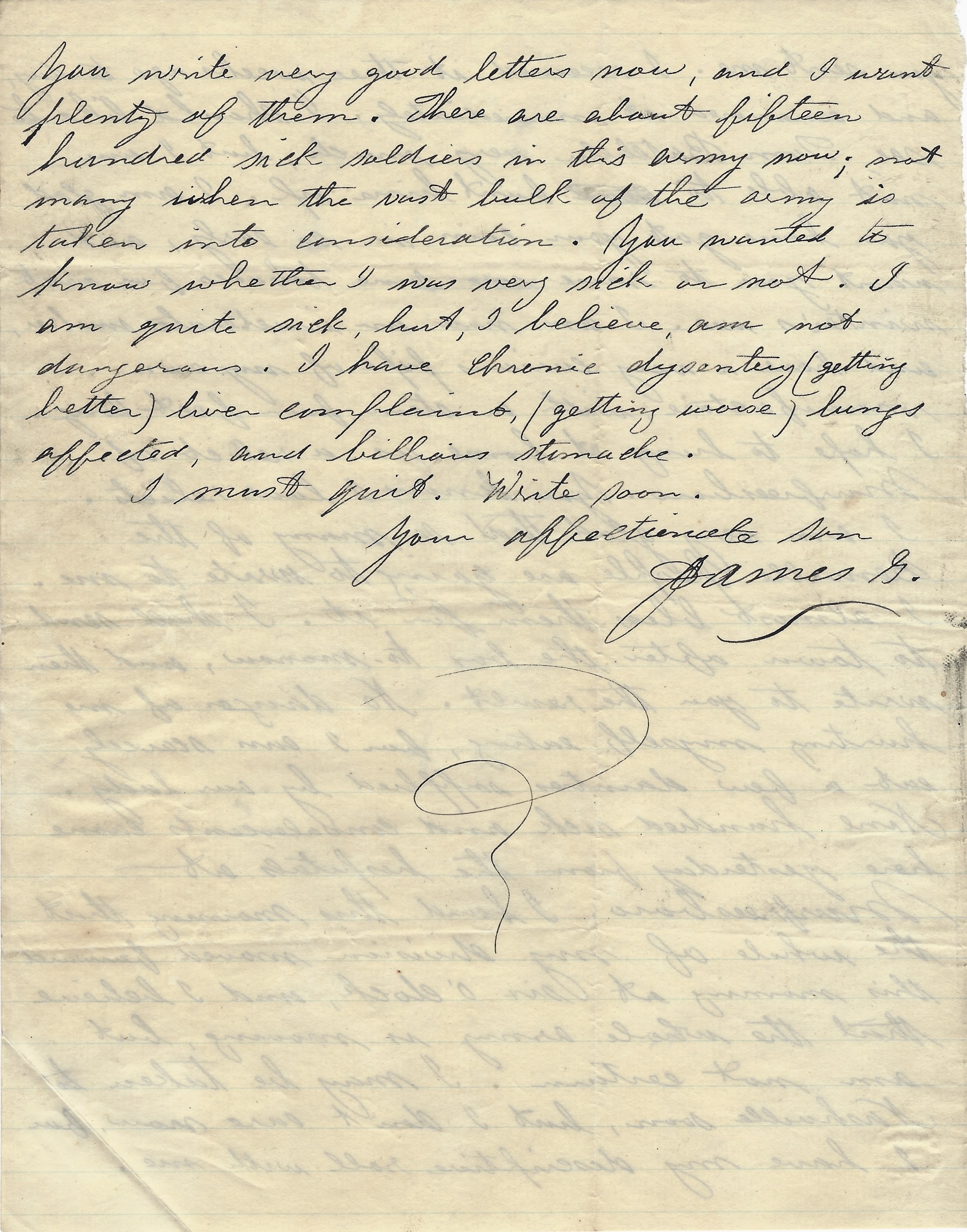

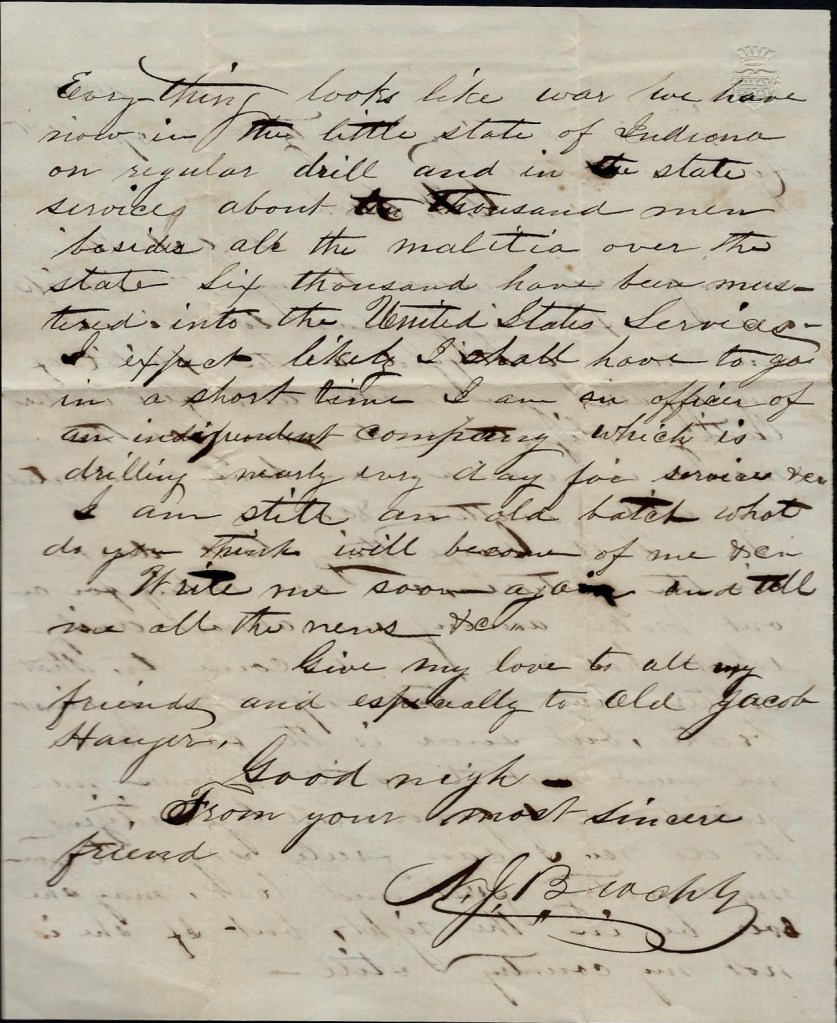

This diary fragment of unbound pages only spans the period from October 19, 1862 through November 11, 1862 while James was absent without leave from the army, hiding out at his home in Jennings county, Indiana. We learn from the diary fragment that he spent his time reading, writing and drawing while he earned money working at the cane mill or cutting wood for the Passmore family. His last entry expresses his deep concern for his arrest by the county sheriff or a provost marshal and his fear of being shot for desertion. He provides a brief summary of how he came to enlist in the army, his endless troubles with physical illness while a soldier, and of his intentions to leave the state and go to Western Pennsylvania to avoid arrest. Some time after this last entry, we know that James was arrested and taken to Indianapolis where he was held awaiting trial as a deserter. A set of letters written in April and May 1863 informs us how he avoided trial and sentencing, see—1863: James Andrew Guirl to his Family.

Though I could find no public record to confirm my suspicions, it’s my personal belief that James suffered from a psychological disorder which he described as “nervousness.” His anxieties reached a level that one might say he suffered from paranoia. One better educated than myself in psychiatry might be able to accurately diagnose his condition based on his diary and letters. One of his dreams is extensively detailed in his diary and he admits that it was a common reoccurrence and that he suffered from insomnia as a result of these dreams.

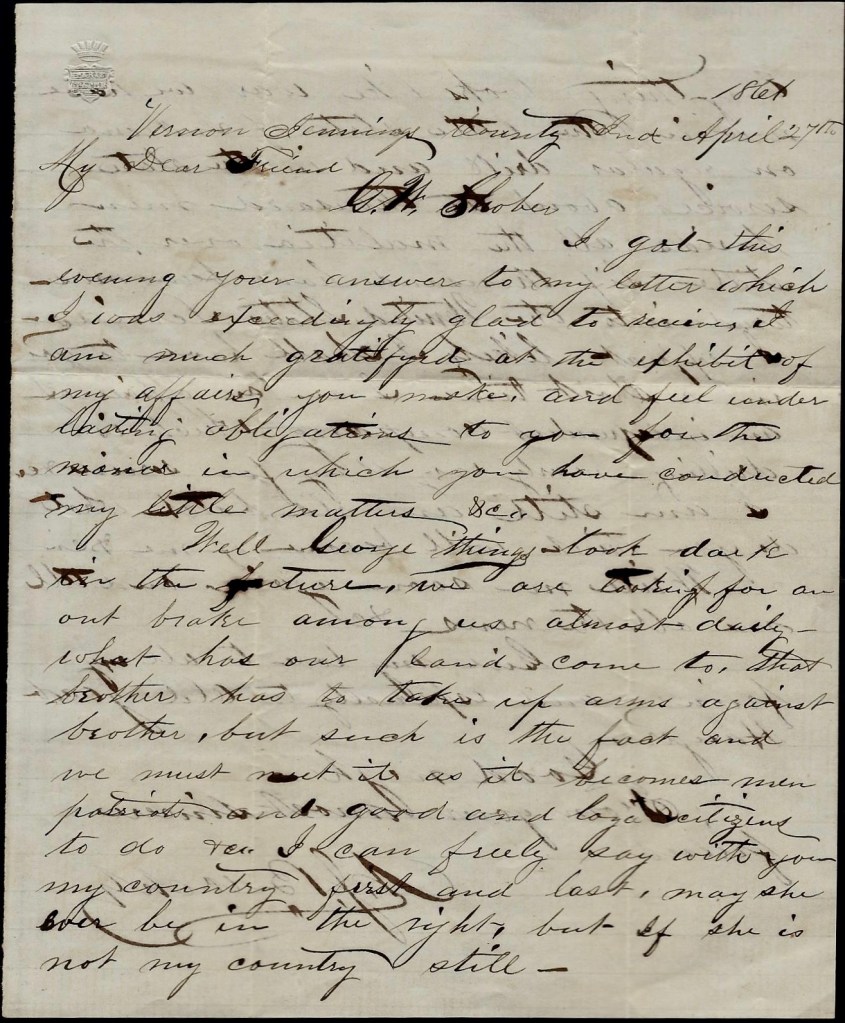

James older brother, William Guirl (1838-1861), served in the same regiment, Co. A, and died at Otterville, Missouri on 15 December 1861. James refers to another brother in his diary—Charles A. Guirl (1836-1870), the husband of Mary Milhous (1832-1884), and the father of two boys, William and Ellet) at the time this diary was penned in 1862. The Guirl family, Mihous family, the Passmore Family and most others mentioned were Quakers and members of the Hopwell Friends Meeting. Much of the area in which these families lived were taken up by the US Government for use as the Jefferson Proving Ground in the 1940s.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

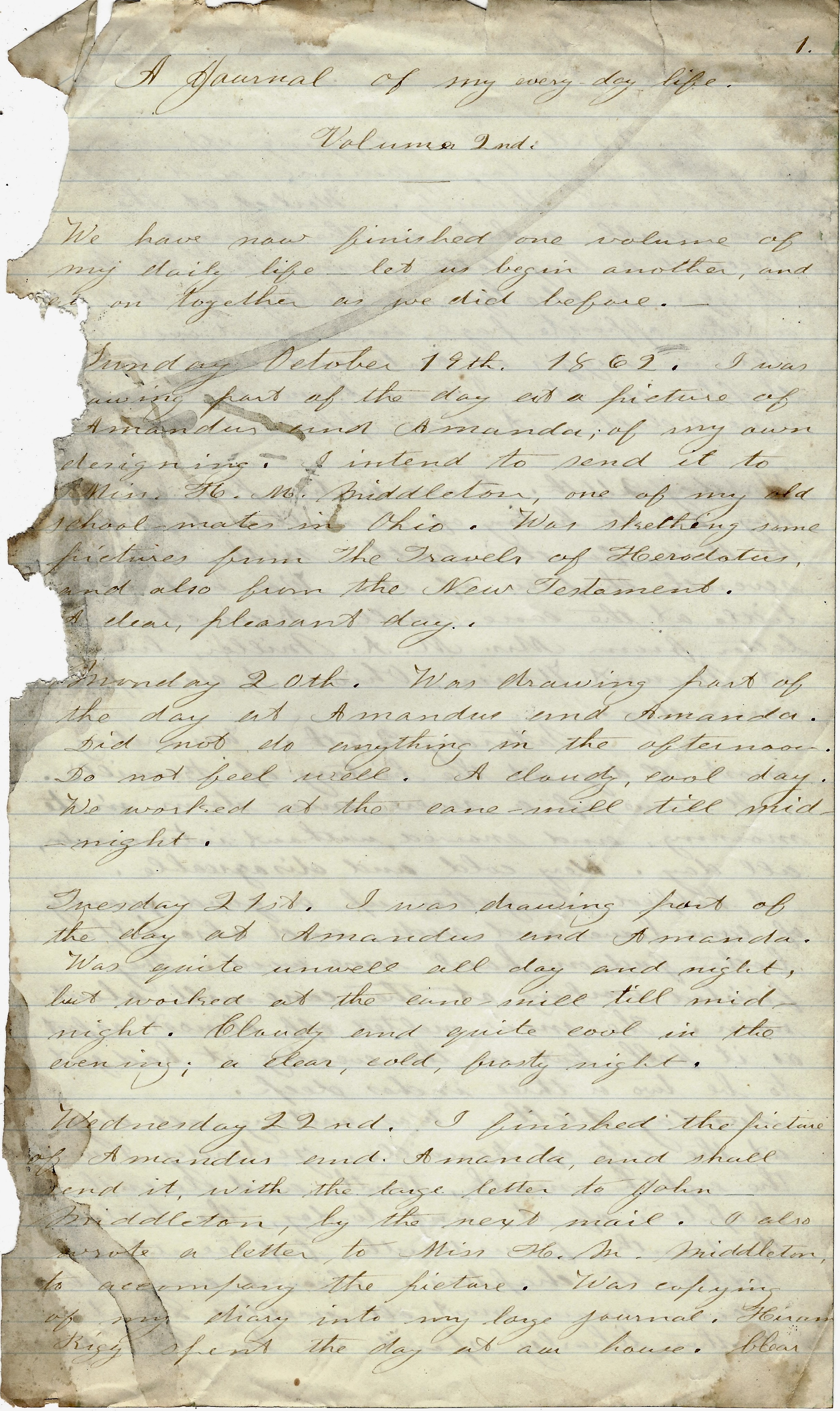

A Journal of my every day life, Volume 2nd

We have now finished one volume of my daily life. Let us begin another and go on together as we did before.

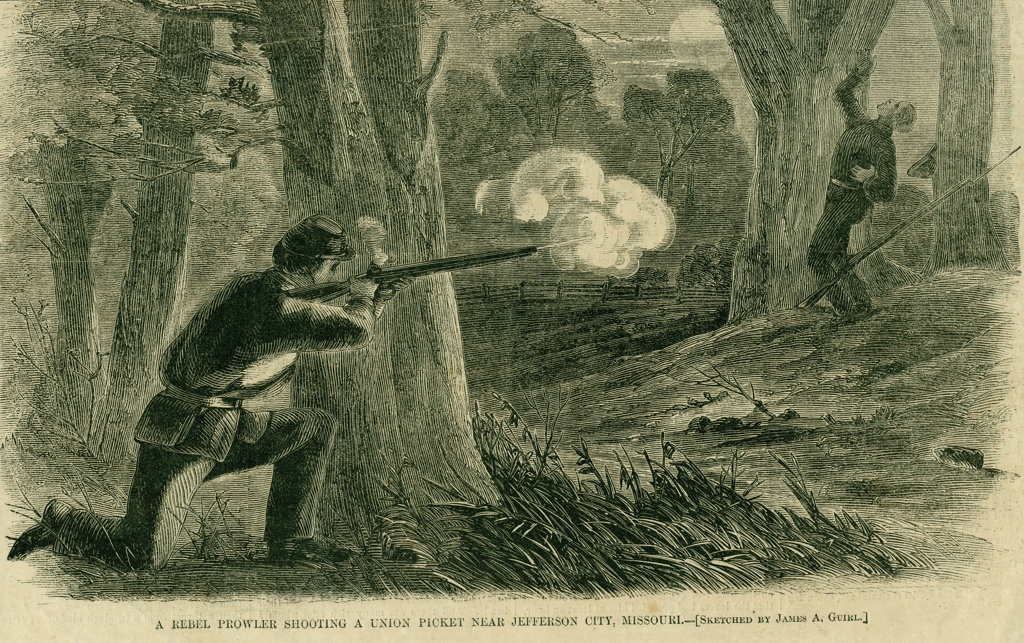

Sunday, October 19, 1862. I was drawing part of the day at a picture Amandud and Amandaof my own designing. I intend to send it to Miss. H. M. Middleton, one of my old school mates in Ohio. Was sketching some pictures from the Travels of Herodotus and also from the New Testament. A clear, pleasant day.

Monday 20th. Was drawing part of the day at Amandus and Amanda. Did not do anything in the afternoon. Do not feel well. A cloudy, cool day. We worked at the cane mill till midnight.

Tuesday 21st. I was drawing part of the day at Amandus and Amanda. Was quite unwell all day and night, but worked at the cane mill till midnight. Cloudy and quite cool in the evening; a clear cold, frosty night.

Wednesday 22nd. I finished the picture of Amandus and Amanda and shall send it with the large letter to John Middleton by the next mail. I also wrote a letter to Miss H. M. Middleton to accompany the picture. Was copying off my diary into my large journal. Hiram Bigg spent the day at our house. Clear and pleasant.

Monday 23rd. Was copying off my diary into my large journal and reading in Tristram Shandy. Worked at the cane mill awhile in the evening. Received a long letter from Miss H. M. Bigg. I also began a History of Benville [Indiana] on the opposite page, and went over to Hiram Bigg’s at dark and wrote two chapters of it. I came home again at 9 o’clock. A clear, pleasant day.

Friday 24th. I was writing part of the day at the History of Benville. I finished the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th chapters of it. Was working a little at the cane mill. Received a letter from Mrs. M. A. Miller living in Mt. Union, Ohio. A clear, pleasant, warm day.

Saturday 25th. Was writing most all day at the History of Benville. It came up a severe snow storm in the morning and snowed without intermission all day. Very cold and disagreeable. I helped to gather up a good quantity of cane leaves and seeds, and also helped brother Judson haul some wood. They finished working at the cane mill about noon. The snow melted off almost as fast as it fell, but in the evening it had got to be two or three inches deep.

Sunday 26th. Was writing all day at the City of Benville. Yesterday I wrote the 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th chapters of it, and today the 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th chapters. Cleared away about noon. Snow most all melted away at night. Brother Charley spent an hour or two with us.

Monday 27th. I was writing all day at the History of Benville. Wrote the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th chapters of it. Clear and cool.

Tuesday 28th. I wrote the 21st chapter of the History of Benville, and chopped a half cord of wood for Joseph and George Passmore. Hiram Bigg and Hannah Walton spent the evening at our house. Cloudy and cool.

Wednesday 29th. Chopped a cord of wood for Joseph and George Passmore. It took me all day. How awful tired I am. Clear and pleasant.

Thursday 30th. Wrote a letter to Mrs. Mary A. Miller, one to Mrs. E. Sanders, and a long one to Miss H. M. Bigg. I also cut some wood for Joseph and George Passmore. Clear, warm, and pleasant.

Friday 31st. I chopped a cord and a half of wood for Joseph and George Passmore, and wrote the 22nd and 23rd chapters of the History of Benville. Clear, warm, and pleasant.

Saturday, November 1st. I chopped a cord of wood for Joseph and George Passmore, and took a little one-horse wagon and went with Hannah Walton to the farm where Mrs. Pamela Smith formerly lived, got several bushels of potatoes, and came home in the evening. A clear, pleasant day.

Sunday 2nd. I wrote the 24th chapter of the History of Benville. Was also reading a little in Tristram Shandy. In the evening I wrote two letters for a poor old mulatto living near named Dunken [Duncan] McDowell, commonly called “Old Dunk.” He has lately become slightly insane and one of the letters which I wrote for him was an earnest appeal to “His Excellency Abraham Lincoln,” to put his late Emancipation Proclamation in immediate force, or else give the negroes the power to fight for their liberty. 1

Hiram Biggs and Hannah Walton spent part of the evening at our house. A bright, warm morning. Clouded up at nine. Began raining at ten and continued slowly most all day. Quite cool in the evening.

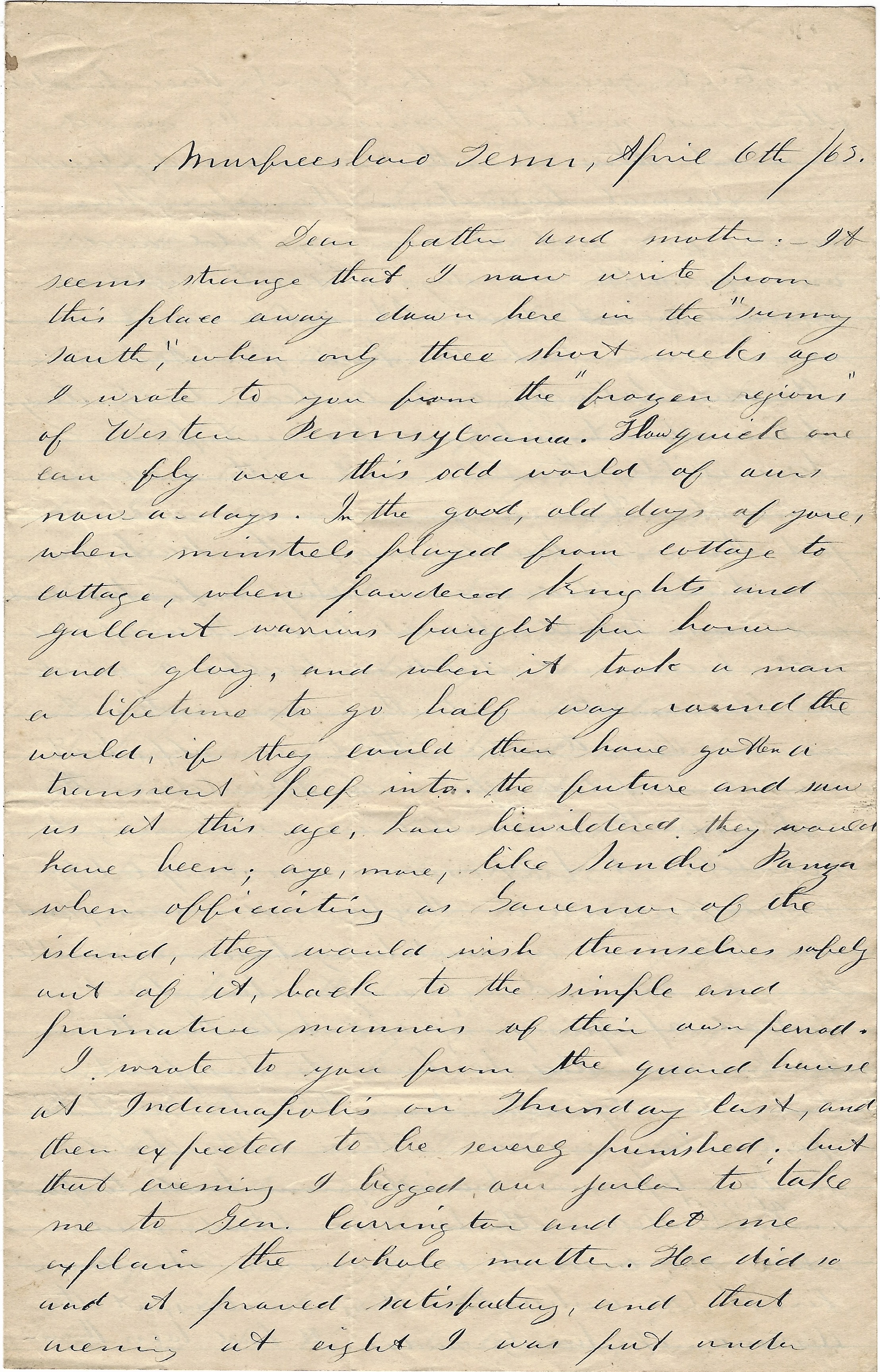

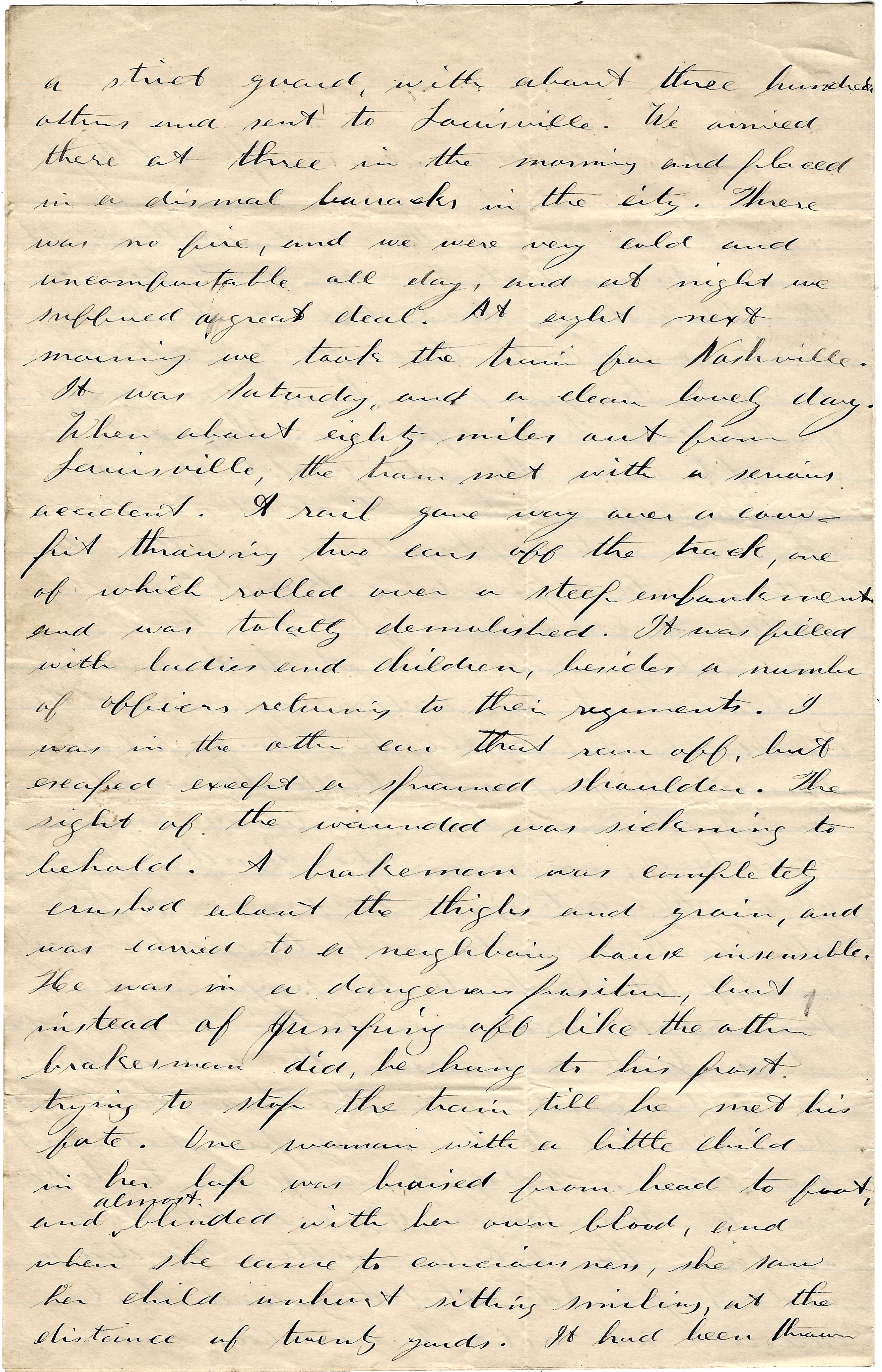

Monday 3rd. I chopped a cord of wood for Joseph and George Passmore; half of it beech and half of it gum. I have decided to leave here soon and go to Cincinnati and probably on to Uncle Thomas J. Myrer’s in Western Pennsylvania. My old Captain [Michael] Gooding of the 22nd [Indiana] Regiment, now Colonel of the same, came home a few days ago slightly wounded in the head. He received it in the Battle of Perryville in Kentucky. He told my brother Charley that I was a deserter and that he was going to take measures to affect my arrest immediately and send me to the army for severe punishment—probably to be shot. But I am going to take measures to make my escape if possible. I have been meanly treated by my regimental officers. I have expected to see the sheriff out after me every day since I made my escape from the Soldier’s Home at Indianapolis. Every time a small wooden bridge near our house rumbles by someone passing over it, I make haste to peep out to see whether it is the sheriff or not.

My dreams every night are chases and captures and court martials, always closing with my death. Last night I dreamed that a large number of officers and men surrounded our house and attempted to take me prisoner, but I succeeded in getting safely away to the distance of several hundred yards when I was discovered by my pursuers and a terrific chase began. Never before did my long legs serve me so faithfully as then. I flew like an arrow over a vast plain, jumping stumps, logs, fences, and runs in my way, hotly pursued by a large band of furious savages eager to drag me to a cruel and bloody death. At length I was brought to a stand on the edge of a giddy precipice with a roaring stream of water beneath. There seemed no possible chance for my escape now. The precipice was before me and my pursuers gradually forming themselves into a semicircle were closing in upon my right and my left, and upon my rear. The very earth seemed to tremble with the loud and repeated cheers of the furious body of men as they rapidly closed upon their defenseless prey. Their eyes gleamed like fire and their lips was covered with a phosphorescent foam, making them look like hideous demons. I gave myself up at last and fell to the ground in a paroxysm of fear and despair; but at the moment the lovely Goddess Athena came soaring over the chasm, and, gently raising me in her arms, she bore me safely across the frightful torrent and set me down on the opposite side.

Then what a yell of rage and disappointment echoed across the chasm! Never before did I hear such earthly sounds come from human beings. But in a moment more, a horrible crash accompanied with a roar a thousand times louder than the loudest thunder completely drowned the dismal yells of the infuriated men. It was they shooting at my fair protectren and I, with monstrous siege guns which had somehow or other suddenly planted themselves on the edge of the precipice. A storm of huge balls came flying around us, which threatened our immediate destruction. But Athena, thinking discretion the better part of valor, suddenly disappeared in a cloud leaving me to make my escape if possible.

I started on a brisk run, every now and then stumbling over the great cannon balls strewed in my pathway, which threw me headlong onto the ground. But scrambling to my feet again, I started briskly forward, only to be, the next moment, sent sprawling as before. The roaring of the siege guns ceased not for a moment, and the hailstorm of ball came pouring in around me unceasingly. But by some good fortune, I escaped being hit by them. At length I was startled by a furious yell immediately behind me, and, on turning my head, I saw several of my pursuers with muskets in their hands only a few yards away, coming toward me with the swiftness of the wind. I redoubled my exertions to escape, every moment expecting the reappearance of my protectress Athena to aid my faint [ ] strength, but I looked [ink blotch hides the script]… was useless to assist me against such fearful odds.

I soon came to a huge new log house with no doorways or windows cut out and the cracks between the logs undaubed. Through one of these cracks, not large enough to admit a rat, I crept and lay down close to the wall on the ground. My pursuers arrived upon the spot a moment after and began firing their muskets through the cracks at me. For some time not a ball touched me, but at last, one of the men put the muzzle of his musket through a small hole near my head and fired. The ball passed entirely through my neck and tore up the ground on the opposite side of me. The crimson blood poured out of the wound in two large streams which soon flooded the ground around me, and, in the end, entirely covered me over till I was drowned by it. Of course I knew no more till I awakened next morning. Such dreams as these disturb me every night. I suffer all the horrors of death but it is very pleasant the next day to think over all my escapes and feelings and the sensation which I felt while dying. A clear, pleasant day.

Tuesday 4th. I chopped a load of beech and maple wood for Joseph and George Passmore. In the evening, Judson and I took the violin and went over to Hiram Bigg’s. Hiram was not at home and Mrs. Miller and her children were there. First place, Judson played the “fiddle” while Hannah Walton and I kicked up our heels in a “stag dance” around the room. Next we rested and smoked a cigar. And last we played blindman’s bluff, children and all, till we were all tired. Then we kissed all round, shook hands, and “Kinnix” and I took our departure for home. A clear, warm, pleasant day. Bright and lovely moonlight at night.

Wednesday 5th. I rose this morning with a horrible tooth-ache, and, after breakfast, went to the woods to chop wood; but my tooth pained me so that I threw my ax down and came to the house. I wrote the 25th chapter of the History of Benville and read a little in Tristram Shandy. After dinner, I went to the woods again and chopped wood till three o’clock when it began to rain. George Bland came to our house in the evening and stayed all night. Clear till noon; rained all night.

Thursday 6th. I chopped two cords of maple and oak wood for George and Josepg Passmore. Brother Charley removed today into the house near here, formerly occupied by Marb. Cook. I spent a few minutes there in the evening with the family, James Painter, and “Good Robin Williard.” Clear, warm and pleasant till most evening, when it clouded over and snowed at night.

Friday 7th. A cold, snowy morning. I was looking over my Magazines and sitting by the fire all the morning. Should I go away, I shall have to sell all my dearly beloved books and pictorial papers to help defray my expenses on the journey. I shall regret to part with Don Quixote, Children of the Abbey, Up the Rhine, Tristram Shandy, Sentimental Journey, Scottish Chiefs, &c. It was for this reason that I was assorting them over this morning. I received a letter from Miss H. M. Middleton living near Alliance, Ohio. Also received a long letter from Miss H. M. Bigg. Afternoon, it cleared away and before night the snow all melted off. Very cold and disagreeable.

Saturday 8th. I designed and drew the outlines of a picture called “Dar-thula.” from Ossian’s Poems. I think a great deal of this sketch and shall take it with me to Cincinnati. to show to the artists there. I wrote a long letter to Miss H. M. Middleton and read an excellent story called Thrown Together. A clear, cold, disagreeable day. One year ago today I arrived home from the army.

Sunday 9th. I was drawing part of the day at a picture of Morning which I began several weeks ago. I want to finish it now and send it to Miss H. M. Middleton. Brother Charley, his wife and children, spent the day at our house and in the evening we all went home with them. Hiram Bigg and Mrs. Hannah Walton were there also. We all stayed till bed time. A clear, pleasant day.

Monday 10th. I cut a cord of wood for Joseph and George Passmore. I want to start away on Wednesday or Thursday next. At noon I went over to Hiram Bigg’s for a few minutes. I was drawing all the evening till late bed time at the picture of Morning. I am making it with minute dots of the pen, a forming a very pretty effect of light and shade. Hiram Bigg spent the evening and night at our house. He sat up with me till bed time writing a voluminous record of his daily life. A clear, pleasant day.

Tuesday, 11th [November 1862]. I am in a desperate situation at this time! Governor Morton has issued an order to Sheriffs and Provost Marshalls in the various counties throughout the State [of Indiana] to immediately arrest all deserters, stragglers, and soldiers who may be home without leave of absence, and send then to Indianapolis for trial. No doubt but a great many of them will be shot. I have no money or else I should have left ‘ere this. I shall try to borrow a little this evening or early tomorrow morning. It seems that I was born to bad luck and constant misfortune. Probably the scale will turn soon. My misfortunes began on the unfortunate day that Master Horace Boston [Barton?] 2 threw me down on the frozen ground. Ever since then my life has been one continual disappointment and draw back. I went to Cincinnati to become a great painter, and came home in a short time a beggar. I joined the army and fell sick in four weeks afterward. I went again and in four weeks more, I was again taken sick and lay in the hospital for eight weeks. I at last got home on a thirty day furlough more dead than alive. My furlough was never renewed and for a long time I violated the army law by not returning to my regiment. At last I started but before I reached the end of my journey, I came near dying and was again sent home more dead than alive. Then I went to Indianapolis to get a discharge but was arrested and sentenced to work six months upon the breastworks at Memphis, Tennessee. I made my escape and came home again, more dead than alive. Then I was advertised as a deserter and shall now have to flee for my life. This has taken most all my patriotism away and the whole country may go to “Old Nick” for all I care.

God knows whether I will ever get clear of this dreadful misfortune. Every night comes the horrors of a disturbed mind in dreams that haunt me throughout the entire day. Mental misery is the most acute of all our many distresses.

1 Free Black Duncan McDowell is mentioned frequently in connection with George Waggoner’s Underground Railroad Station #4 which was located near Big Graham Creek. Fugitives slaves were sent from Benville to Waggoner’s farm and from there McDowell conducted them to Waddle’s Grist Mill, then on to Dr. Andrew Cady’s Station at Holton. McDowell is listed among the best known conductors along this route. He lived near Bethel Hole. [See: Southeastern Indiana’s Underground Railroad Routes and Operations, 2001]

2 I have not been able to identify Master Horace Barton (or Boston) was but my hunch is that he may have been a school master at the Quaker school that James attended in Ohio. He doesn’t give the name of the school but he mentions acquaintances in Mount Pleasant so I’m inclined to believe James attended the Mount Pleasant Friends Boarding School in Mount Pleasant.