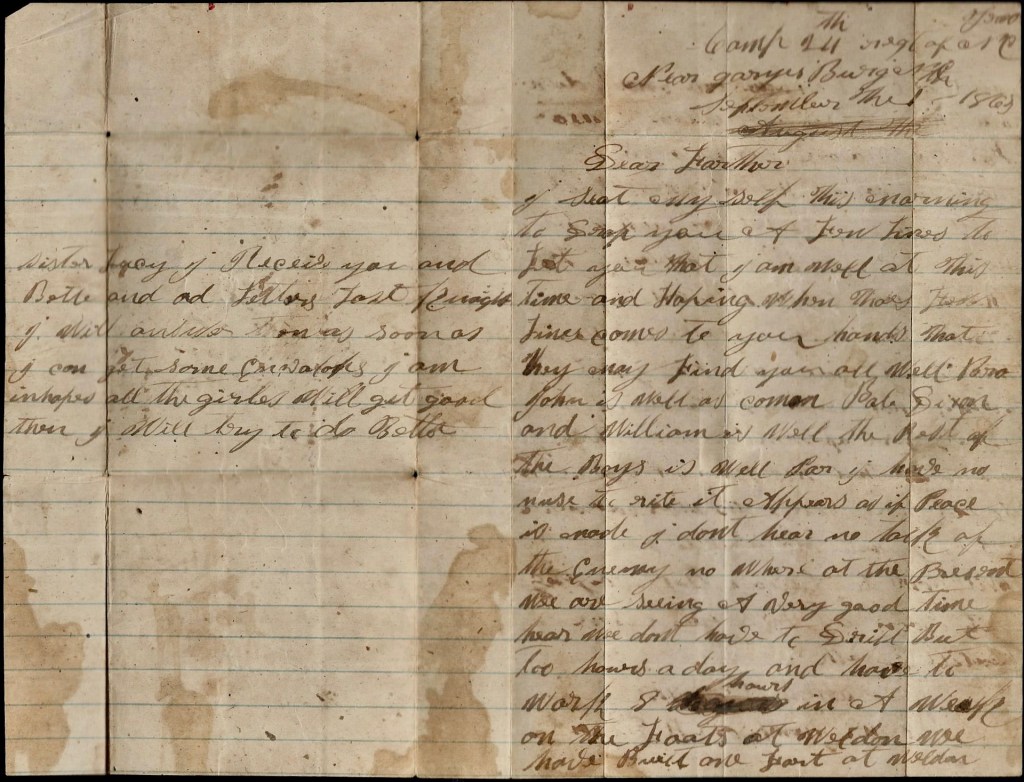

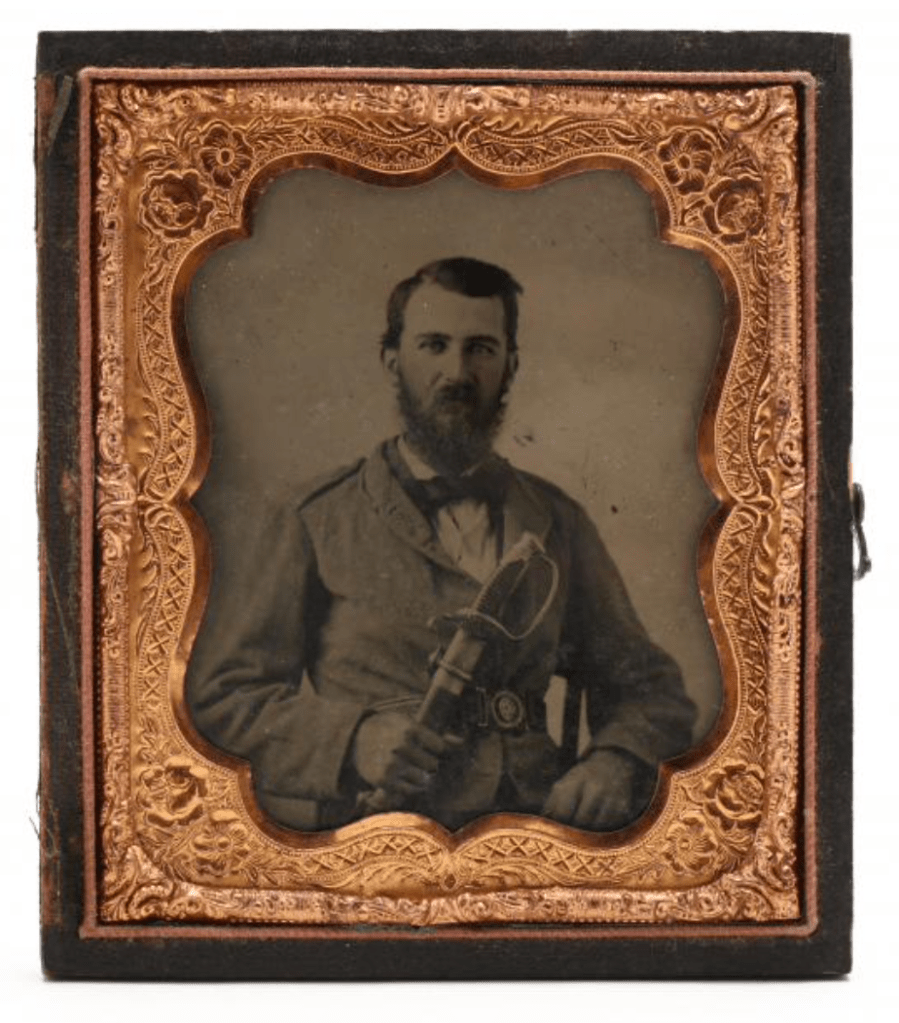

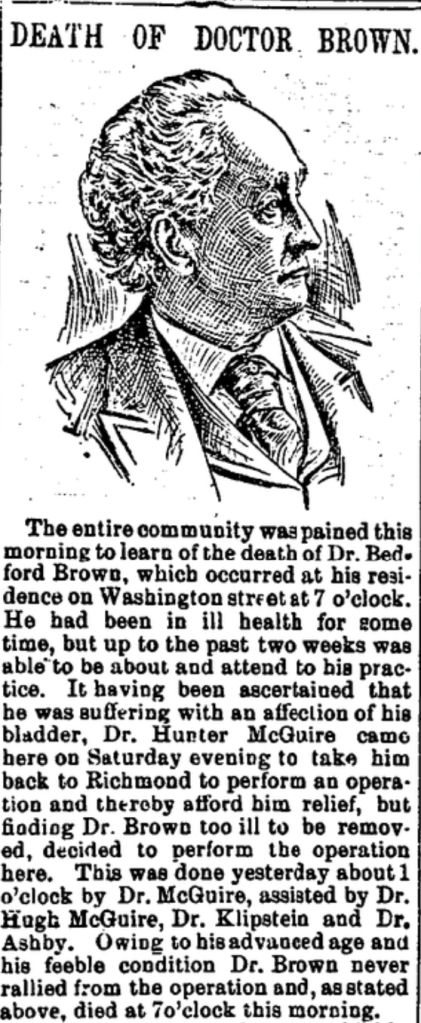

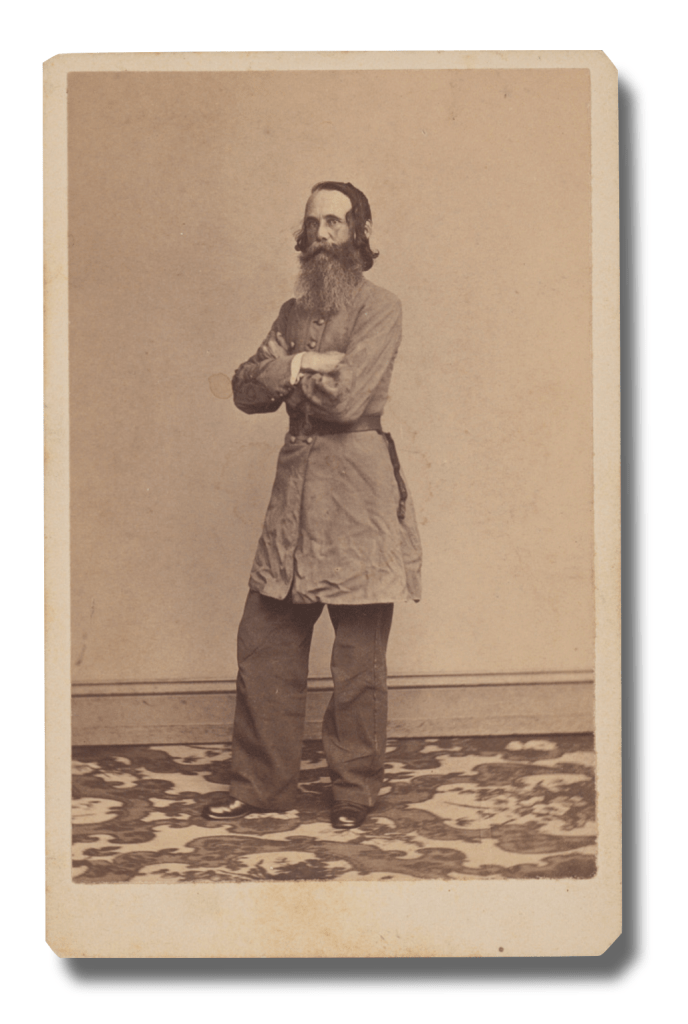

The following letter was written by Pvt. Sidney T. Dixon (1840-1864) of Co. H, 24th North Carolina Infantry (formerly the 14th North Carolina Infantry). According to muster records, Sidney enlisted on 1 March 1862 for the duration of the war. He seems to have been present with the regiment most of the time until 21 May 1864 when he died at Chester Station from wounds received at Bermuda Hundred.

Sidney and his brother John C. Dixon (b. 1841)—who served in the same company, were the only sons of Thompson H. Dixon (1805-Bef1900) and Elizabeth Lucy Walters (1814-Bef1900) of Allensville, Person county, North Carolina. John Dixon enlisted in June 1861 (when the regiment was the 14th N. C.) and served until 28 February 1865 when he finally deserted. The other Dixon boys mentioned in the letter were probably cousins.

By the time of Sidney’s death in 1864, the regiment had seen action in the Seven Days Battles, the Maryland Campaign, the Battle of Fredericksburg, and the action around New Berne and Plymouth in North Carolina. Specifics are lacking as to where Sidney was wounded but it was likely in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff in mid-May, 1864.

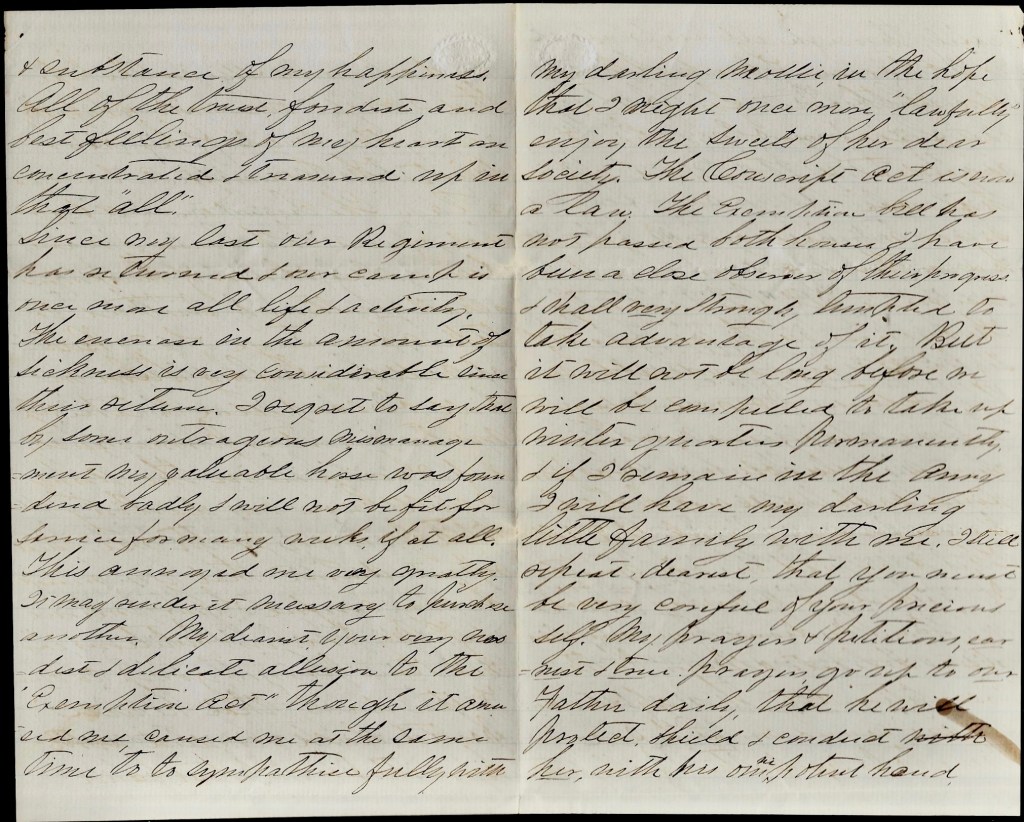

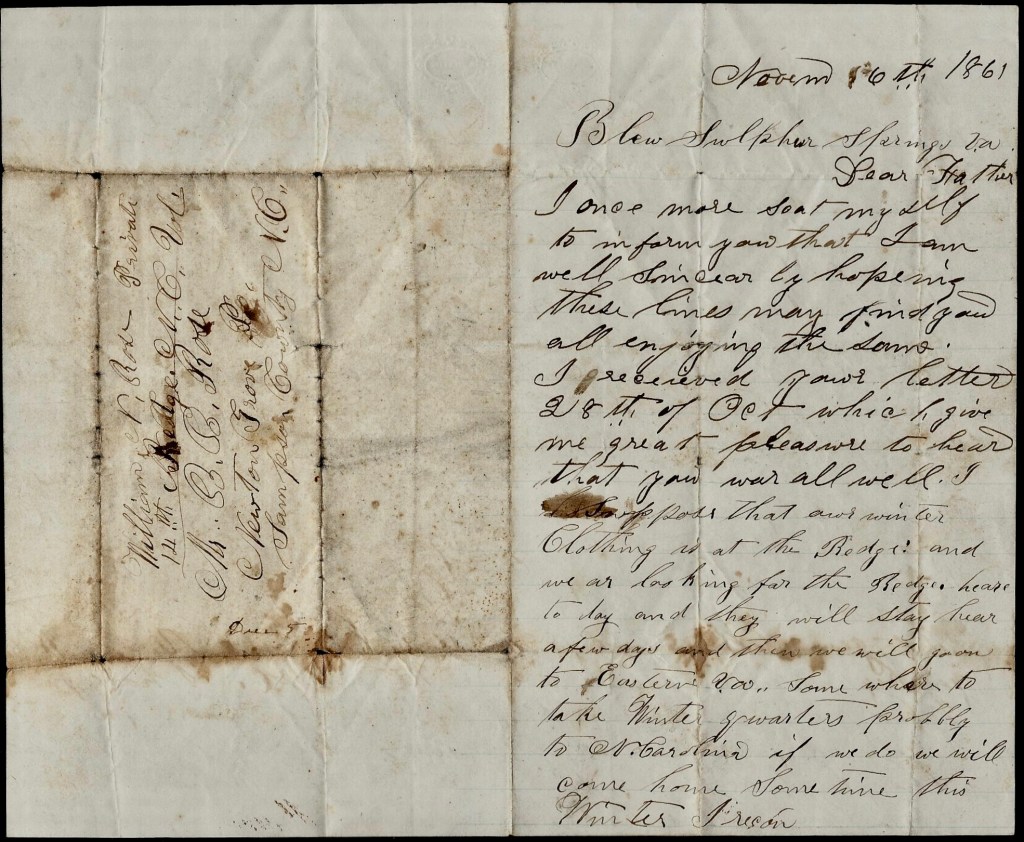

Transcription

Camp 24th Regt. of N. C.

Near Garysburg, North Carolina

September 1st 1863

Dear Father,

I seat myself this morning to drop you a few lines to let you [know] that I am well at this time and hoping when these few lines comes to hand, that they may find you all well. Bro. John is well as common. Bob Dixon and William is well. The rest of the boys is well.

Par, I have no news to write. It appears as if peace is made. I don’t hear no talk of the enemy no where at the present.

We are seeing a very good time here. We don’t have to drill but two hours a day and have to work 8 hours in a week on the forts at Weldon. We have built one fort at Weldon and got another one most done. We have very cool weather here for the season.

Par, let as many hold up for Old Holden 1 as will, but don’t you never let no such a set turn you to be a Holdenite for there is not a smart man in our army that would take up for him. It is true, there is a great many that hold up for him, but what sort of men are they? They are ones that has been a disadvantage to us ever since the war commenced.

So as I have no more to write, I will come to a close by saying write soon. As ever your son until death, — Sidney T. Dixon

To Mr. Thompson H. Dixon

Sister Lucy, I received yours and Bette’s letters last night. I will answer them as soon as I can get some envelopes. I am in hopes all the girls will get good. Then I will try and do better.

1 “Old Holden” is a reference to William Woods Holden (1818-1892)—a newspaper editor who used the press to criticize the Confederate government and by 1862, to rally support for a peace movement in North Carolina. He ran for the Governor’s seat in 1862 but failed.