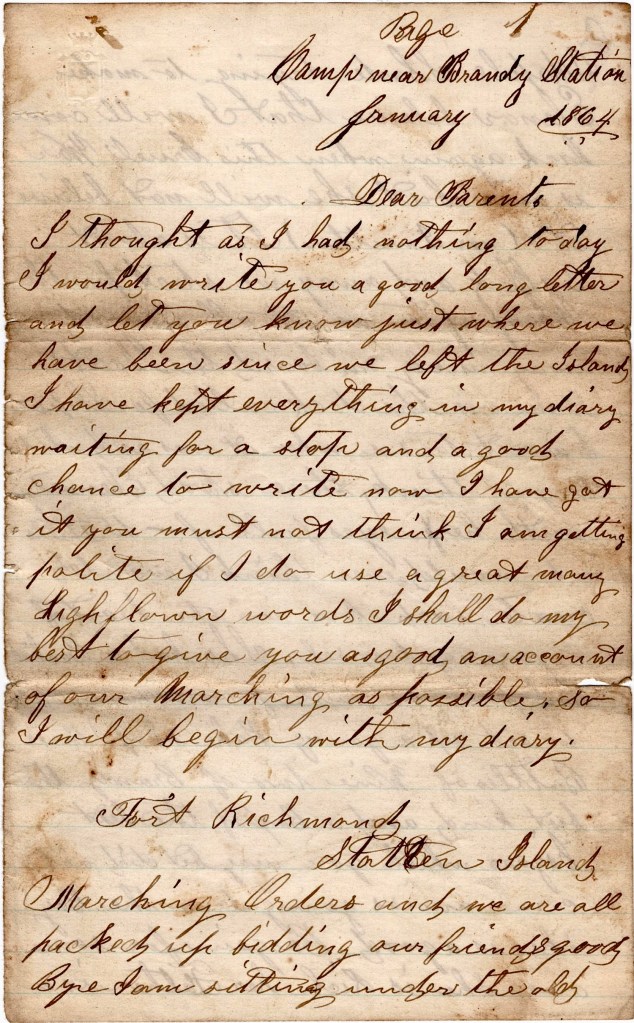

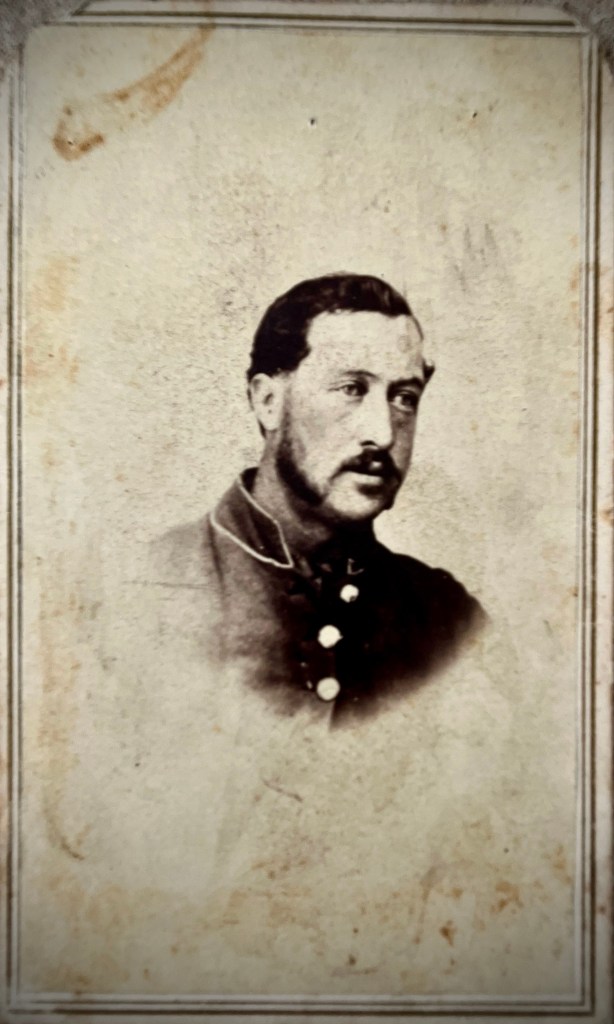

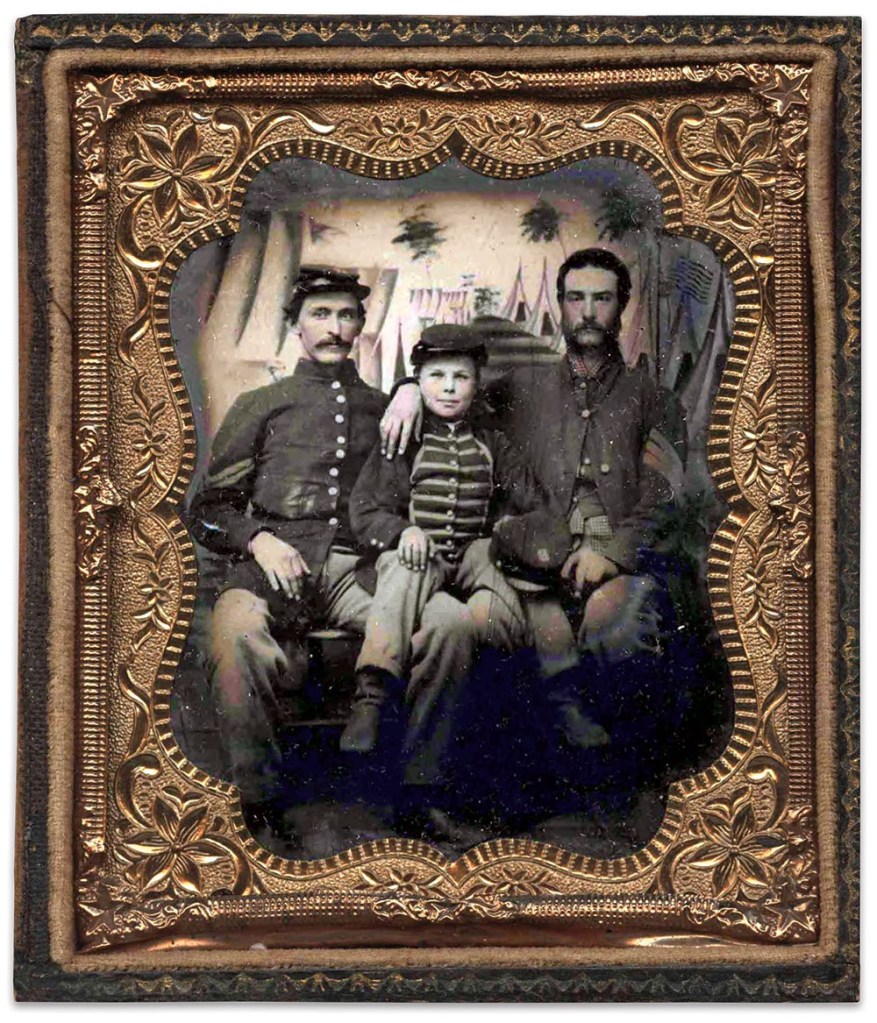

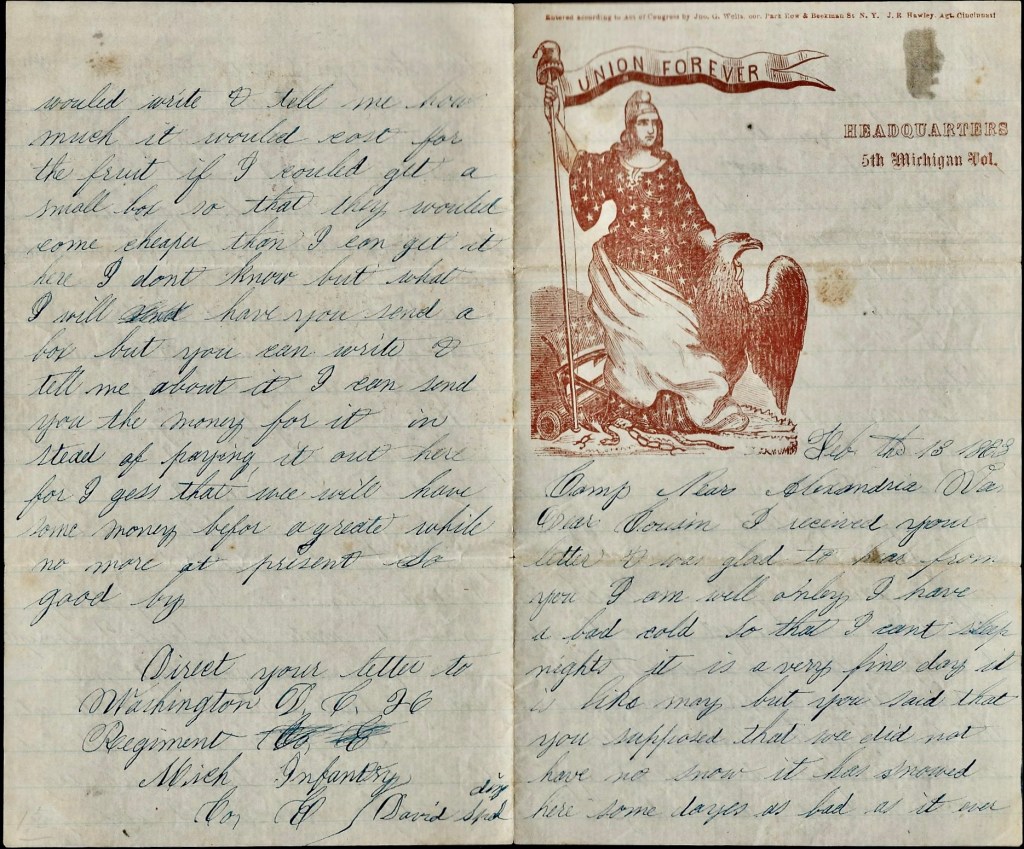

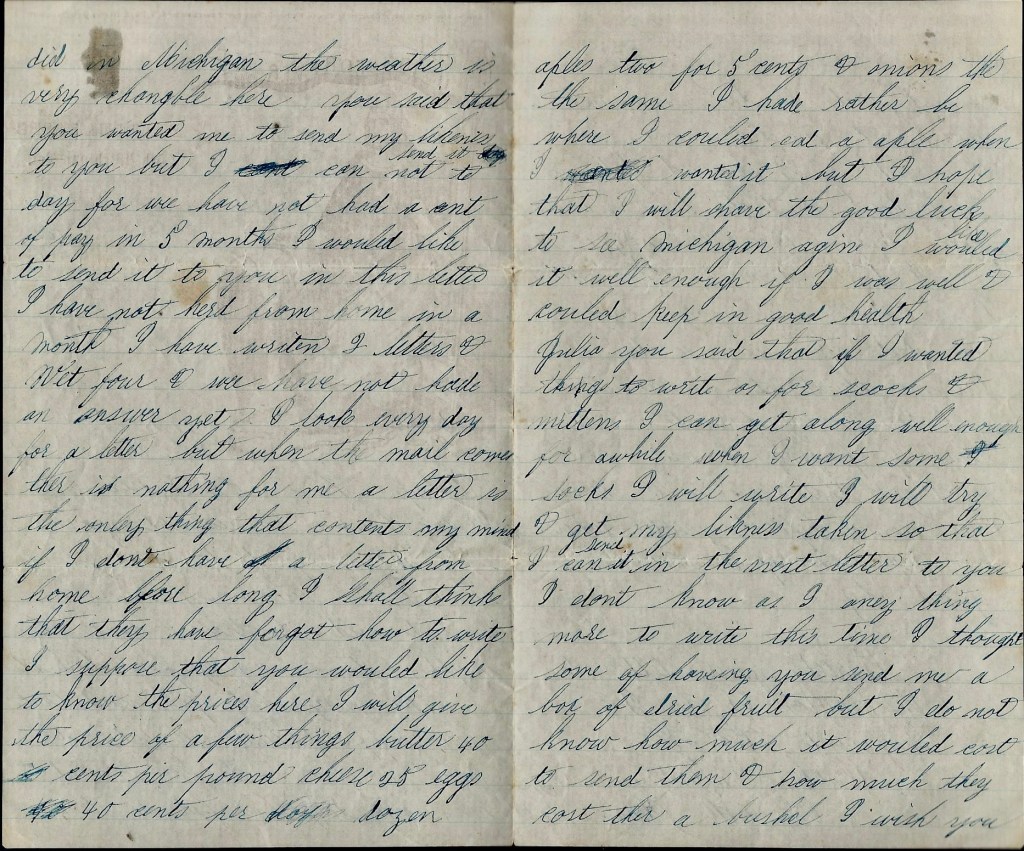

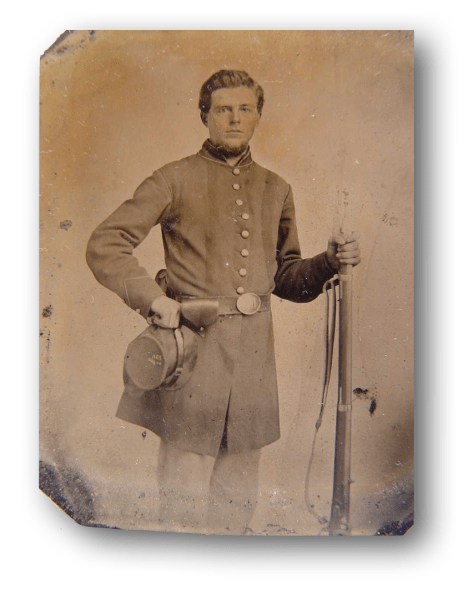

The following letter was written by Nelson W. Shephard (1844-1864), the son of Orrin W. Whephard (1818-1888) and Sarah Ann Demming (1820-1897) of Croton, Newaygo county, Michigan. Nelson was born in 1844 near Grass Lake, and had moved to Newaygo County with his parents, Orrin and Sarah. Before heading off to war, Nelson served some time in Jackson State Prison for burglary before heading off to war in August 1862 when he enlisted in Co. C. 26th Michigan Infantry. Although a poor speller, Shephard provided many details about his experiences in the 26th Michigan in letters home to his parents.

Nelson’s wartime experiences would likely have remained unknown were it not for Nancy Crambit, who discovered his letters among her late husband’s possessions, acquired years earlier at a yard sale. Unwilling to retain them, she surmised that someone in Newaygo County might find them meaningful, prompting her to send them to the local post office. For further details, refer to Smithsonian’s website and their magazine article, Mystery Solved: A Michigan Woman Says She Mailed Civil War Letters to the Post Office.

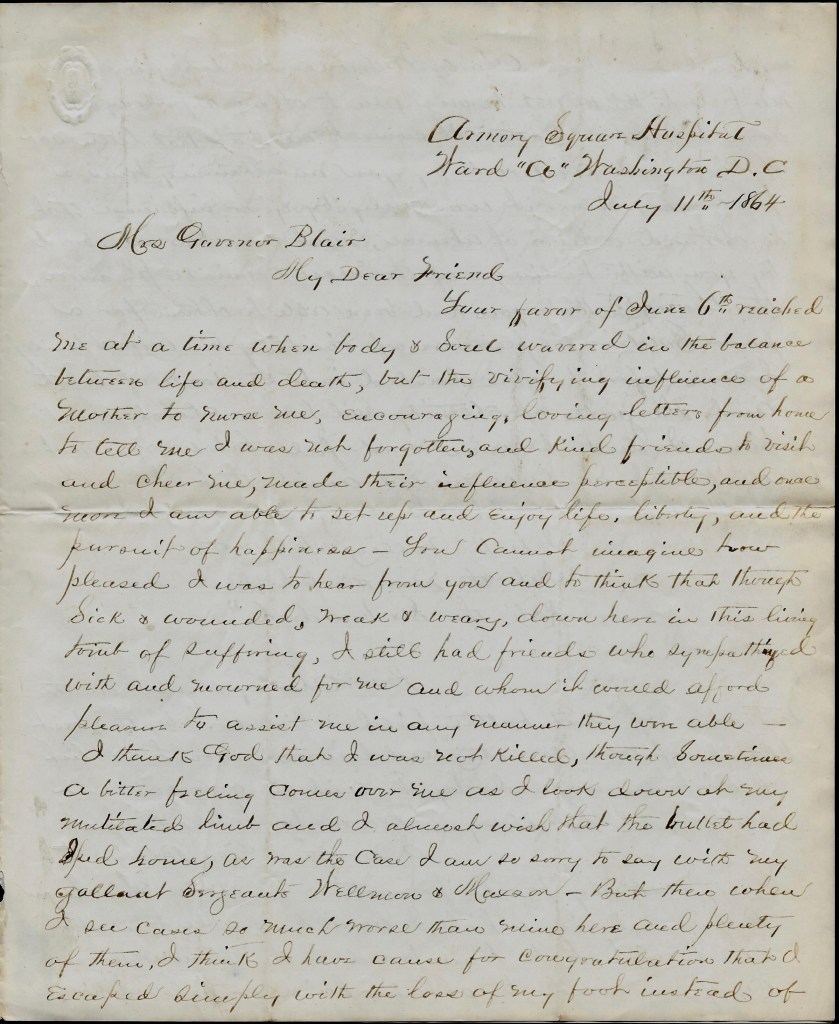

Nelson was taken prisoner at Ream’s Station, Virginia, on 25 August 1864 and was supposedly listed in Belle Isle Prison at Richmond, Virginia on October 4, 1864. He died in the Confederate Prison at Salisbury, North Carolina on December 18, 1864, where he had been joined by other members of the regiment.

Nelson’s lengthy letter presented here captures his regiment’s movements from Fort Richmond on Staten Island to Brandy Station in November 1863 until early January 1864—particularly the Mine Run Campaign. More of his letters can be found here: 1862-64: Nelson W. Shephard to his Parents on Spared & Shared 22.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Camp near Brandy Station

January 1864

Dear Parents,

I thought as I had nothing today I would write you a good long letter and let you know just where we have been since we left the Island, I have kept everything in my diary waiting for a stop and a good chance to write. Now I have got it. You must not think I am getting polite if I do use a great many highflown [highfalutin] words. I shall do my best to give you as good an account of our marching as possible. So I will begin with my diary.

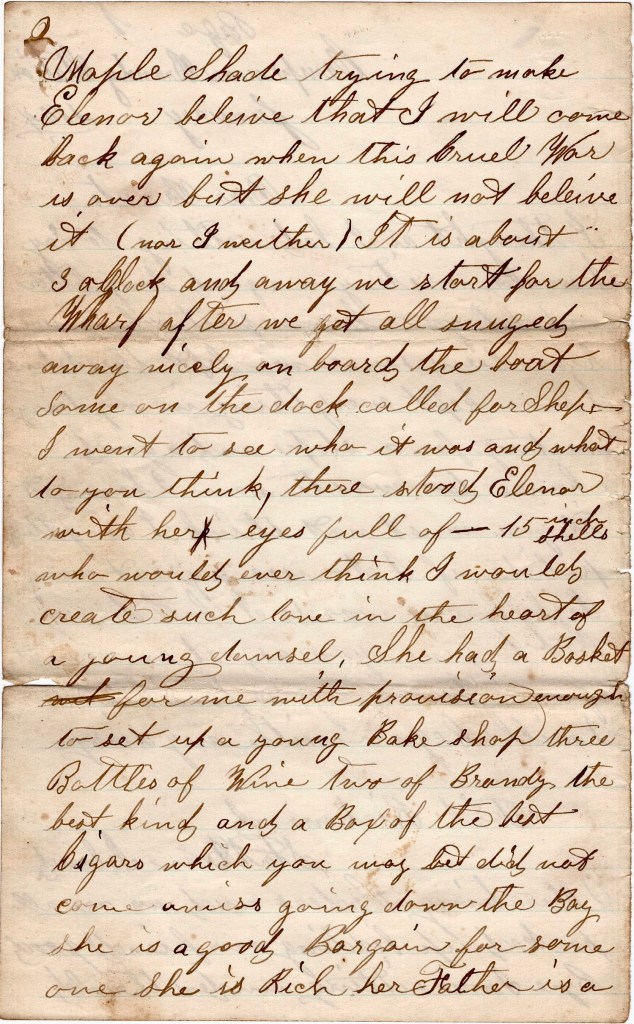

Fort Richmond, Staten Island. Marching orders and we are all packing up bidding our friends goodbye. I am sitting under the old Maple shade trying to make Elenor believe that I will come back again when this cruel war is over but she will not believe it (not I neither). It is about 3 o’clock and away we start for the wharf. After we got all snugged away nicely on board the boat, someone on the dock called for Shep. I went to see who it was and what do you think, there stood Elenor with her eyes full of—–15 inch shells. Who would ever think I would create such love in the heart of a young damsel. She had a basket for me with provisions enough to set up a young bake shop, the bottles of wine, two of brandy—the best kind, and a box of the best cigars which you may bet did not come amiss going down the Bay. She is a good bargain for someone. She is rich. Her Father is a retired merchant from New York City. But we will let that drop and get out of Long Island Sound into Raritan Bay.

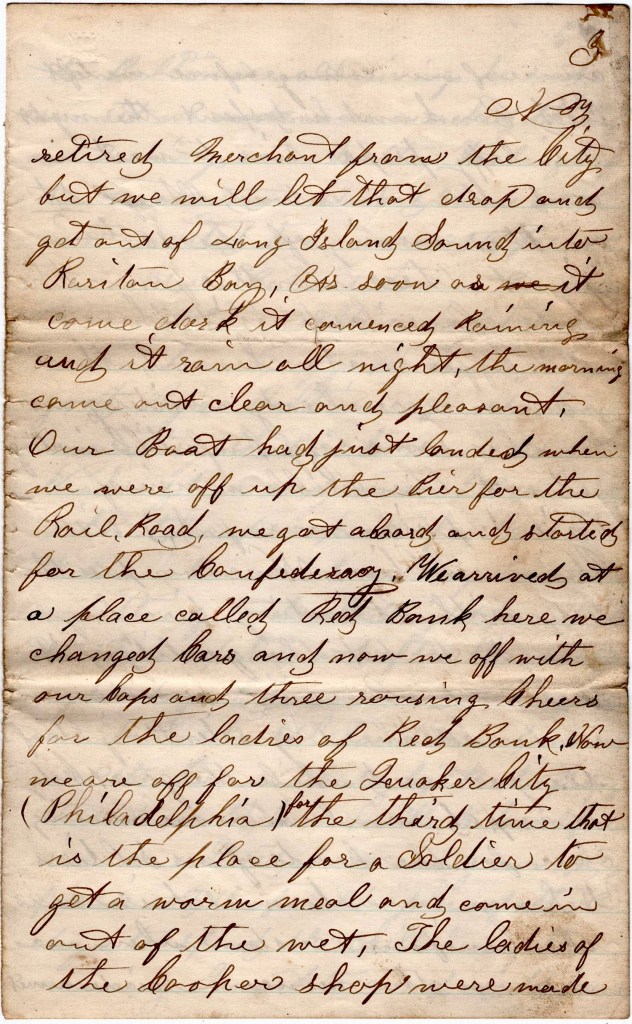

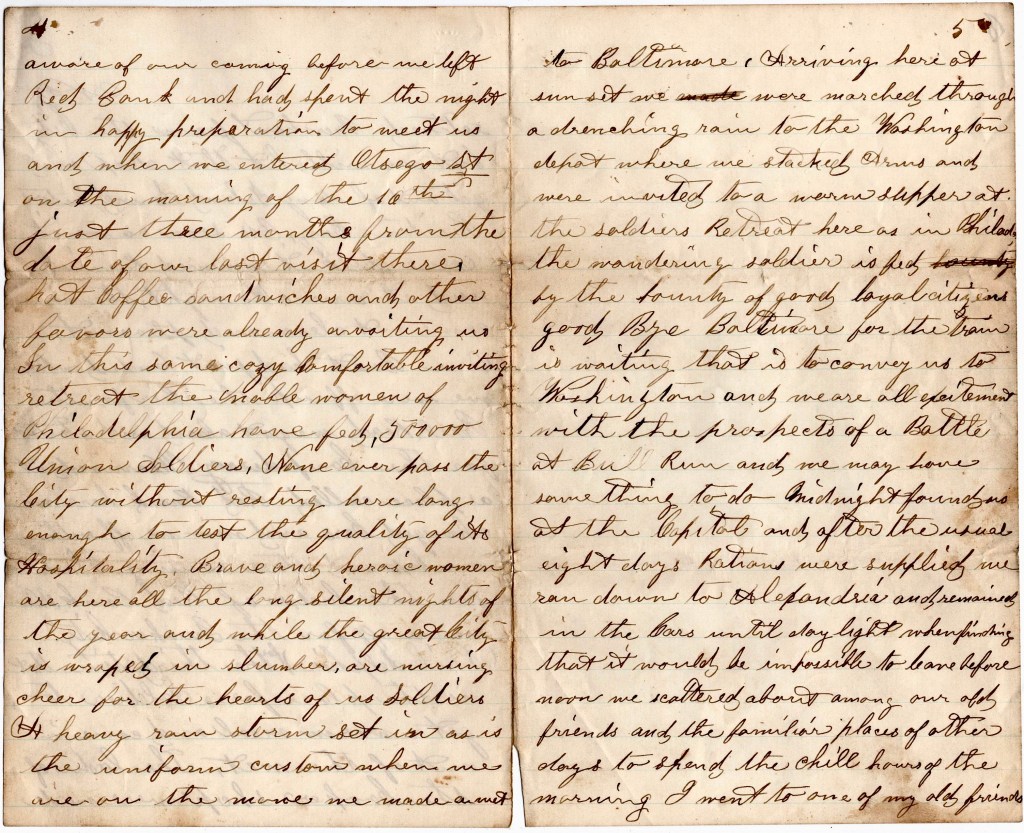

As soon as it became dark, it commenced raining and it rained all night. The morning came out clear and pleasant. Our boat had just landed when we were off up the pier for the railroad. We got aboard and started for the Confederacy. We arrived at a place called Red Bank. Here we changed cars and now we off with our caps and [gave] three rousing cheers for the ladies of Red Bank. Now we are off for the Quaker City (Philadelphia) for the third time. That is the place for a soldier to get a warm meal and come in out of the wet. The ladies of the Cooper Shop were made aware of our coming before we left Red Bank and had spent the night in happy preparation to meet us. And when we entered Otsego Street on the morning of the 16th, just three months from the date of our last visit there, hot coffee, sandwiches, and other favors were already awaiting us. In this same cozy, comfortable, inviting retreat the noble women of Philadelphia have fed 500,000 Union soldiers. None ever pass the City without resting here long enough to test the quality of its hospitaliy. Brace and heroic women are here all the long silent nights of the year and while the great City is wrapped in slumber, are nursing cheer for the hearts of us soldiers.

A heavy rainstorm set in as is the uniform custom when we are on the move. We made a [ ] to Baltimore, arriving here at sunset. We were marched through a drenching rain to the Washington depot where we stacked arms and were invited to a warm supper at the Soldier’s Retreat. Here as in Philadelphia, the wandering soldier is fed by the bounty of good, loyal citizens. Goodbye Baltimore for the train is waiting that is to convey us to Washington and we are all excitement with the prospects of a battle at Bull Run and we may have something to do.

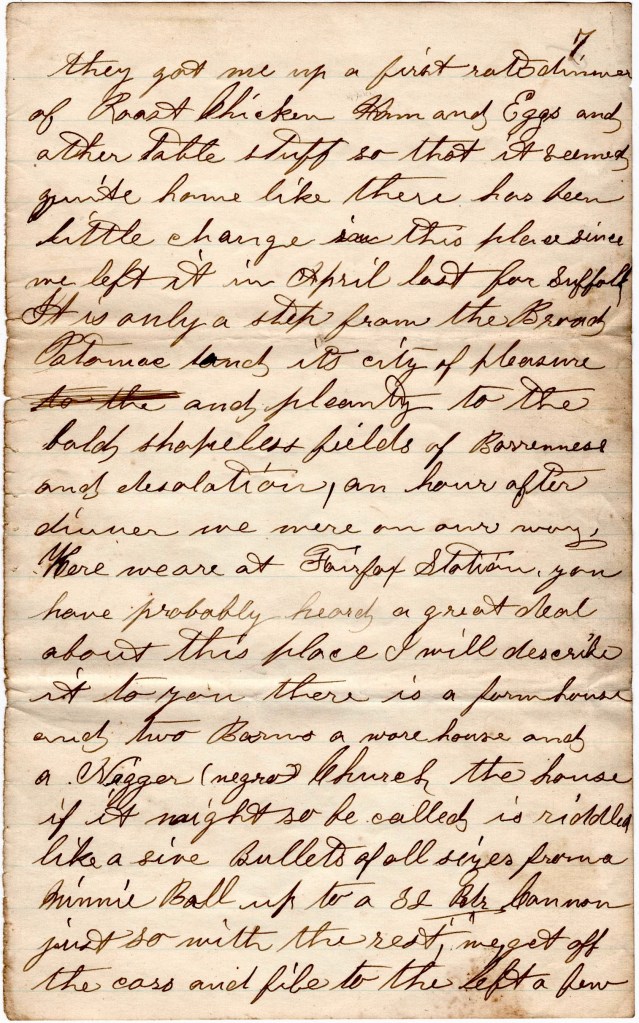

Midnight found us at the Capitol and after the usual eight days rations were supplied, we ran down to Alexandria and remained in the cars until daylight when finding that it would be impossible to leave before noon, we scattered about among our old friends and the familiar places of other days to spend the chill hours of the morning. I went to one of my old friends. They got me up a first rate dinner of roast chicken, ham and eggs and other table stuff so that it seemed quite home like. There has been little change in this place since we left it in April last for Suffolk. It is only a step from the broad Potomac and its cty of pleasure and plenty to the bald, shapeless fields of barrenness and desolation. An hour after dinner we were on our way.

Here we are at Fairfax Station. You have probably heard a great deal about this place. I will describe it to you. There is a farm house and two barns, a warehouse and a Nigger (negro) Church. The house—if it might be so called—is riddled like a sieve. Bullets of all sizes from a Minié ball up to a 32-pounder cannon just so with the rest. We get off the cars and file to the left. A few minutes march brings us to the camp of the 3rd and 5th Michigan Regiments and we are encamped with the Veterans of the Potomac Army. Familiar faces are here and familiar voices greet us from the old Battalions of the Peninsula and Rappahannock. It is a capitol place and we will stop here tonight.

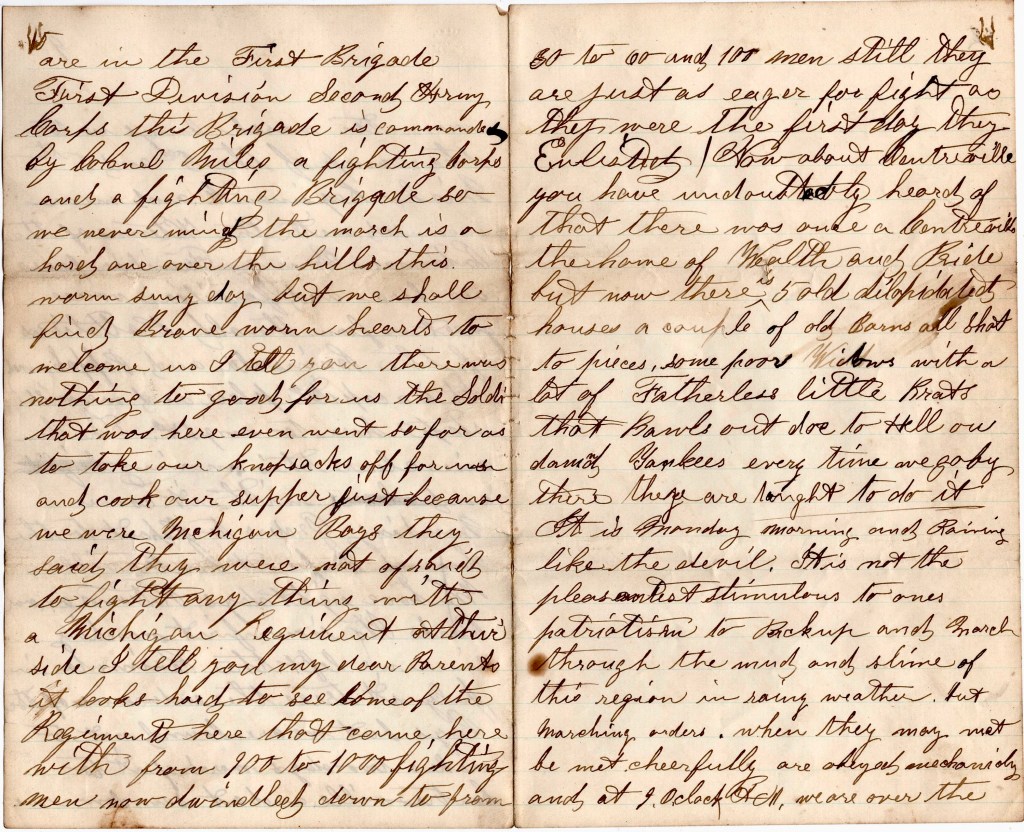

The sun rises clear this morning and with it comes marching orders to report to the Second Corps at Centreville. We have eight days rations on our backs. It is our first marching since we left the Peninsula in July. It tries the endurance of the boys but we are bound not to make a two days march of it to Centreville and at sundown we are in the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, 2nd Army Corps. This brigade is commanded by Colonel Miles—a fighting corps and a fighting brigade, so we never mind. The march is a hard one over the hills this warm, sunny day, but we shall find brave, warm hearts to welcome us, I tell you, there was nothing too good for us. The soldiers that was here even went so far as to take our knapsacks off for us and cook our supper just because we were Michigan boys. They said they were not afraid to fight anything with a Michigan regiment at their side. I tell you, my dear parents, it looks hard to see some of the regiments here that come here with from 900 to 1,000 fighting men now dwindled down to from 30 to 60 and 100 men. Still they are just as eager for fight as they were the first day they enlisted.

Now about Centreville, you have undoubtedly heard of that. There was once a Centreville, the home of wealth and pride. But now there is 5 old dilapidated houses, a couple of old barns all shot to pieces, some poor widows with a lot of fatherless little brats that bawls out, “Go to Hell!” or “Damned Yankees!” every time we go by. There they are tonight to do it.

It is Monday morning and raining like the devil. It is not the pleasantest stimulus to one’s patriotism to pack up and march through the mud and slime of this region in rainy weather, but marching orders, when they may be met cheerfully, are obeyed mechanically and at 9 o’clock a.m. we are over the pontoons that span Bull Run and are marching amid the wrack and ruin of the first and second battles of the same name. This favorite battle ground of the Rebels looks lonely enough in a rainy morning like this. There is so much in all these rude graves—whitened and exposed skeletons of men and animals, broken gun carriages, fragments of shells and muskets scattered around through the tall weeds that have spring up everywhere as if to make the desolation more complete that we are quite ready for another battle to see if we could not make up for what we have lost in these two heavy battles. But we shall not have a chance for General Lee left here this very morning. His campfires are still burning bright. He made up his mind that it would not pay him to fight father Meade.

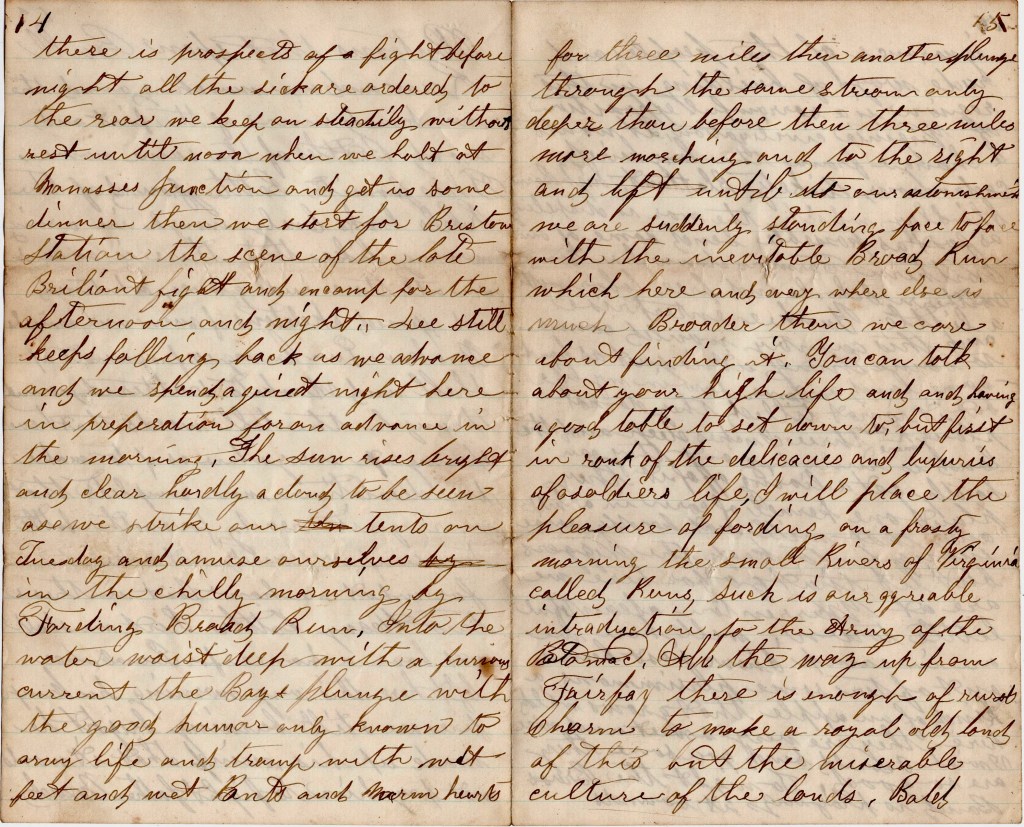

There is prospects of a fight before night. All the sick are ordered to the rear. We keep in steadily without rest until noon when we halt at Manassas Junction and get us some dinner. Then we start for Bristoe Station—the scene of the late brilliant fight—and encamp for the afternoon and night. Lee still keeps falling back as we advance and we spend a quiet night here in preparation for an advance in the morning.

The sun roses bright and clear. Hardly a cloud to be seen as we strike our tents on Tuesday and amuse ourselves in the chilly morning by fording Broad Run. Into the water waist deep with a furious current the boys plunge with the good humor only known to army life and tramp with wet feet and wet pants and warm hearts for three miles. Then another plunge through the same stream, only deeper than before. Then three miles more marching and to the right and left until to our astonishment, we are suddenly standing face to face with the inevitable Broad Run which here and everywhere else is much broader than we care about finding it.

You can talk about your high life, and having a good table to sit down to, but first in rank of the delicacies and luxuries of a soldier’s life, I will place the pleasure of fording on a frosty morning the small rivers of Virginia called Runs. Such is our agreeable introduction to the Army of the Potomac. All the way up from Fairfax, there is enough of rural charm to make a royal old land of this but the miserable culture of the land, bald ignorance of the people and rude ways of building in this region is a sorrowful exposition of Virginia civilization. It wants a change from the long-haired cadaverous, rickety, blatant high-born chivalry, which the war is dispelling as fast as possible. Send some of our Northern farmers down here, some Northern schools, and free labor with a little Yankee enterprise and his country would come to something. It is just as handsome land as I ever saw in my life but it is not tilled. They do not plough more than three inches deep and the land is running out. They can hardly get a living off of it. They plant one kernel of corn in a hill and that will not hardly raise enough to keep the Niggers.

But let that go for her we are at Warrenton—-a beautiful little town. Well, here we are in camp. I have just been out after some persimmons, a kind of apple that grows wild here. They are very sweet and nice. I wish I could send you some. They are so good. Tonight the brass band is playing. It sounds delightful. They are playing Home Sweet Home. I wish I could see it night after night. The strains of the band from Division headquarters have charmed us to sleep, making us forgetful of the rainy days and weary marches. How fast the time goes while we are in camp. We pass the days and weeks in every way peculiar to camp life and if it was not for a new month or pay day or marching orders, we wonder at the unconscious flight of time.

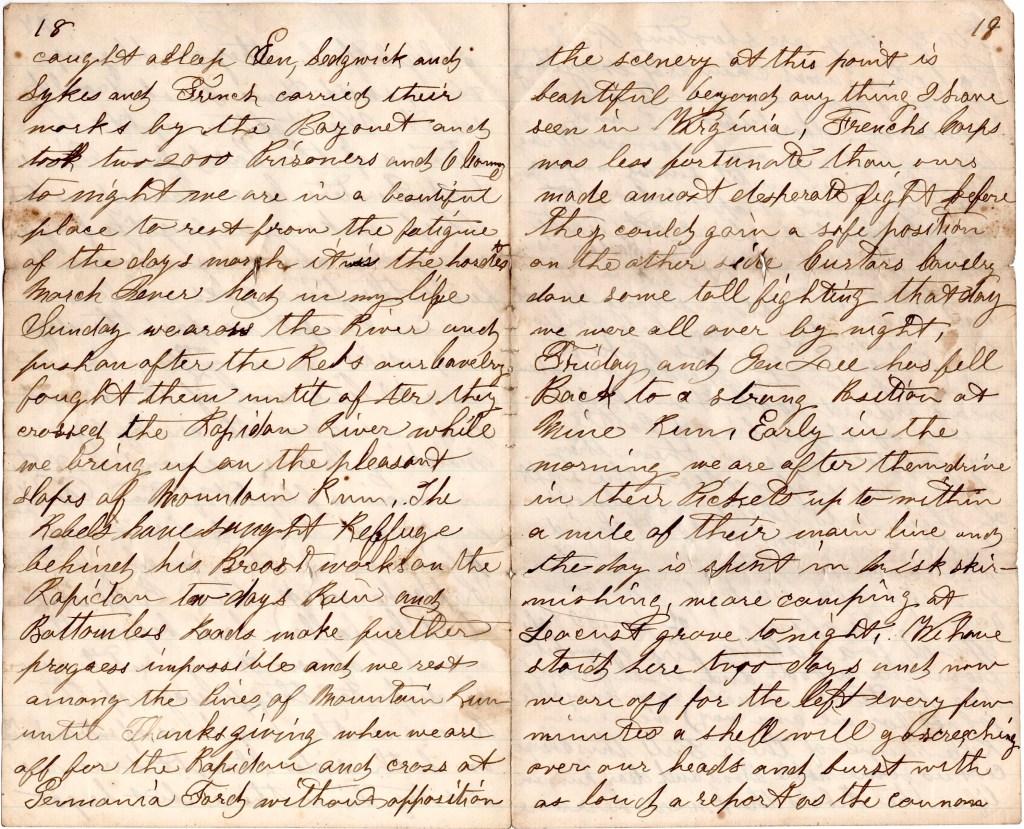

November 7th finds us at the end of rest and pleasure on the march to the Rappahannock. The Rebs have steadily fallen back before the advance of our army until now he disputes the passage of the river with long lines of entrenchments on both sides, thought sure we [would] not try him there, but he got caught asleep. Gens. Sedgwick and Sykes and French carried their works by the bayonet and took 2,000 prisoners and six cannons. Tonight we are in a beautiful place to rest from the fatigue of the days march. It was the hardest march I ever had in my life.

Sunday we cross the river and push on after the Rebs. Our cavalry fought them until after they crossed the Rapidan River while we bring upon the pleasant slopes of Mountain Run. The Rebels have sought refuge behind his breastworks on the Rapidan. Today’s rain and bottomless roads make further progress impossible and we rest among the pines of Mountain Run until Thanksgiving when we are off for the Rapidan and cross at Germania Ford without opposition. The scenery at this point is beautiful beyond anything I have seen in Virginia. French’s Corps was less fortunate than ours, made a most desperate fight before they could gain a safe position on the other side. Custer’s Cavalry done some tall fighting that day. We were all over by night.

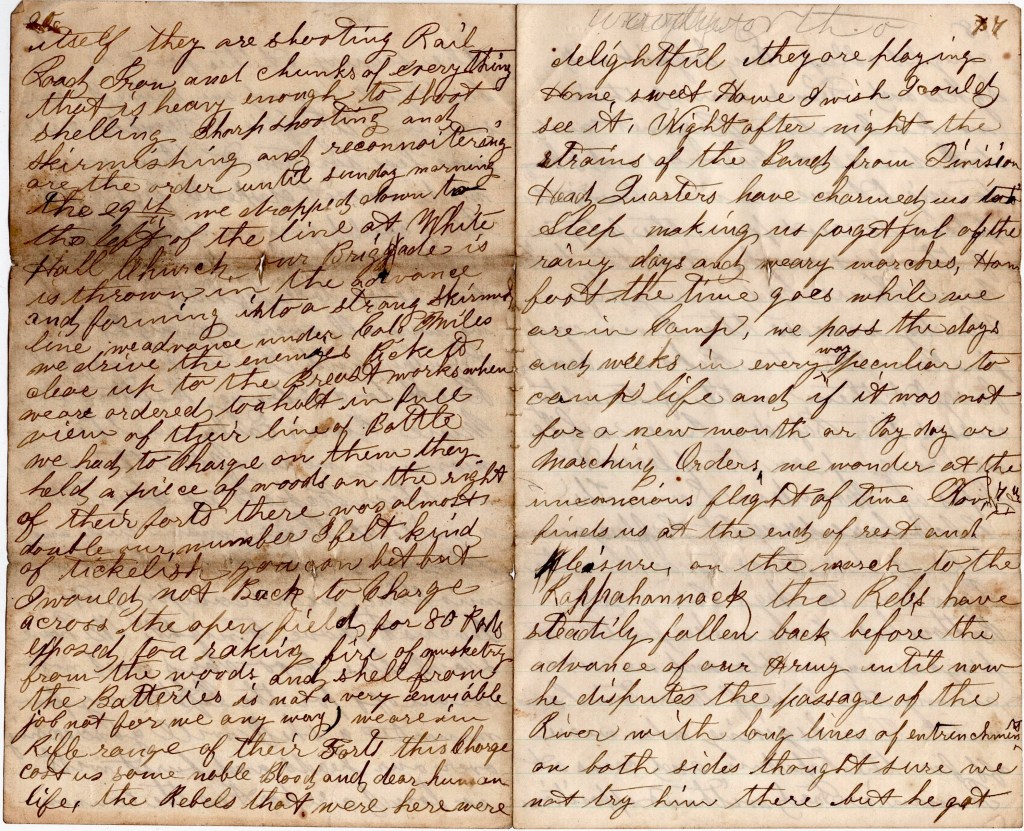

Friday and Gen. Lee has fell back to a strong position at Mine Run. Early in the morning we are after them, drive in their pickets up to within a mile of their main line and the day is spent in brisk skirmishing. We are camping at Locust Grove tonight. We have stayed here two days and now we are off for the left. Every few minutes a shell will go screeching over our heads and burst with as loud of a report as the cannon itself. They are shooting railroad iron and chunks of everything that is heavy enough to shoot. Shelling, sharpshooting and skirmishing and reconnoitering are the order until Sunday morning the 29th [when we] dropped down to the left of the line at White Hall Church.

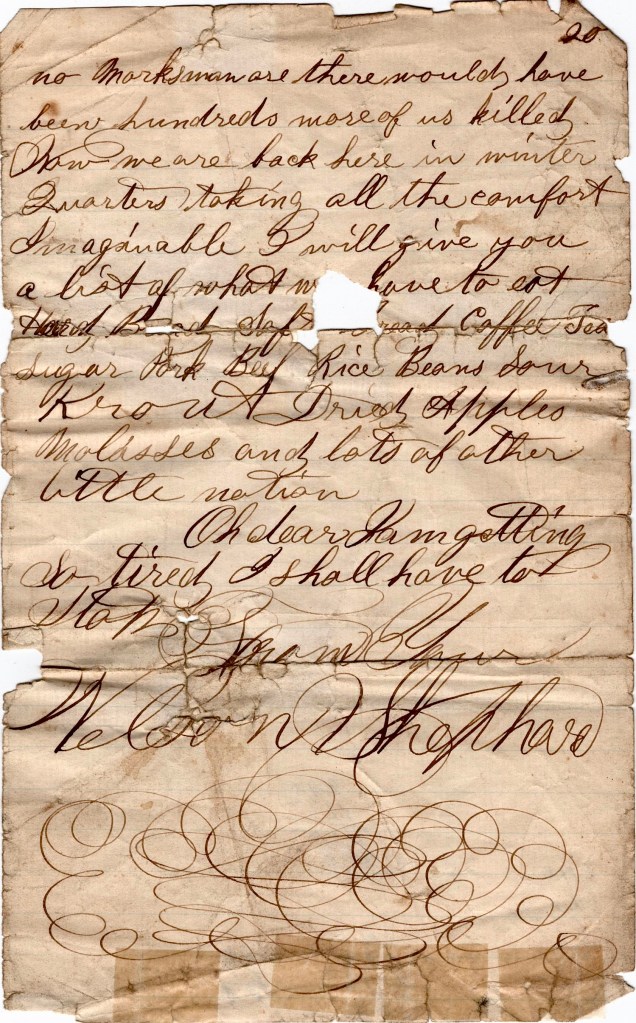

Our Brigade is thrown in the advance and forming into a strong skirmish line. We advance under Col. Miles. We drive the enemy pickets clear up to the breastworks when we are ordered to halt in full view of their line of battle. We had to charge on them. They held a piece of woods on the right of their forts. There was almost double our number. I felt kind of ticklish you can bet but I would not back to charge across the open field for 80 rods exposed to a raking fire of musketry from the woods and shell from the batteries is not a very enviable job—not for me anyway. We are in rifle range of their forts. This charge cost us some noble blood and dear human life. The Rebels that were here were no marksmen or there would have been hundreds more of us killed.

Now we are back here in winter quarters taking all the comfort imaginable. I will give you a list of what we have to eat. Hard bread, soft bread, coffee, tea, sugar, pork, beef, rice, beans, sauerkraut, dried apples, molasses, and lots of other little notion. Oh dear, I am getting so tired. I shall have to stop. From your Nelson Shephard