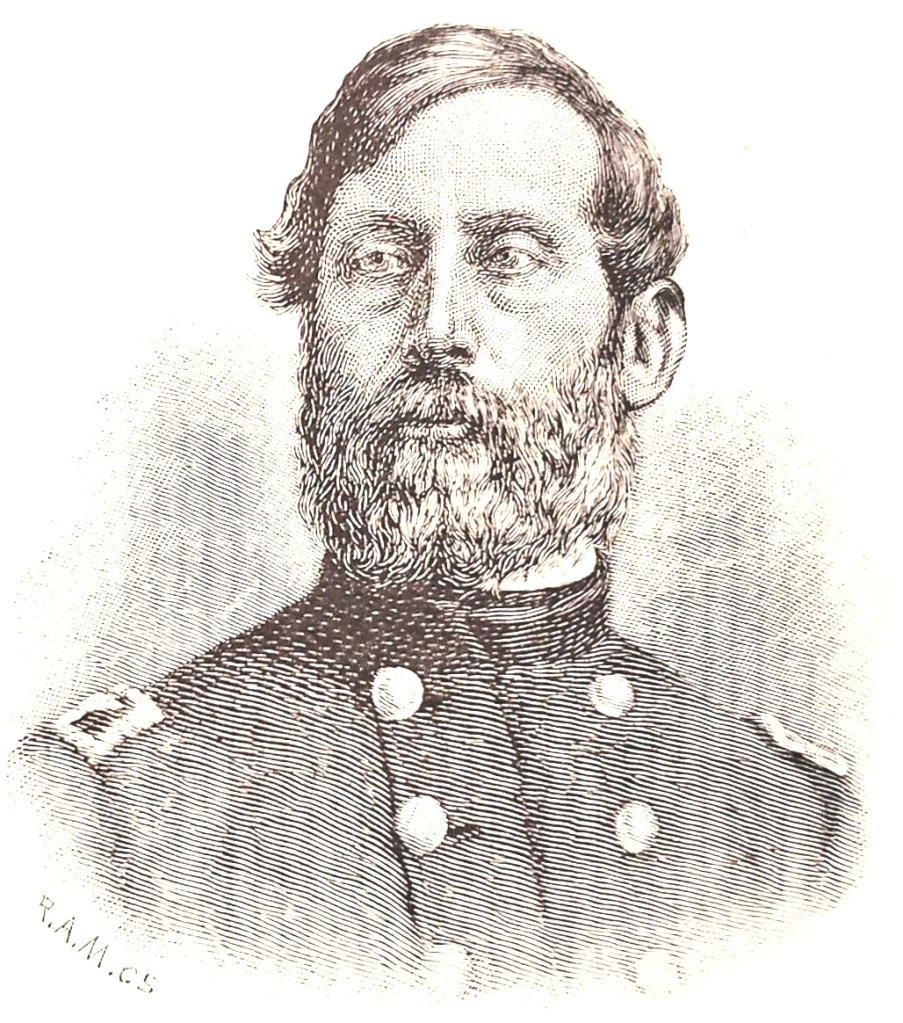

The following incredible letter was written by Mary Bethune (Craig) Hunt (1836-1911), the second wife of (then) Major Henry Jackson Hunt (1819-1889). Hunt’s first wife, Emily C. De Russy, died at Fortress Monroe in 1857 and he took 19 year-old Mary as his second wife in December 1860—just a little over four months before this letter was penned. Mary was the daughter of Henry Knox Craig (1791-1869), the Chief of the US Army Ordnance Bureau. Mary’s mother came from Massachusetts, and had strong ties to the Boston area. She was pregnant with her first child at the time.

Henry Jackson Hunt was a dedicated military officer, graduating from the US Military Academy in 1839. He is predominantly recognized for his role as the Chief of Artillery in the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War, where he earned acclaim from his contemporaries as one of the war’s most formidable tacticians and strategists. When the conflict commenced in 1861, Hunt was stationed at Fortress Monroe commanding his artillery battery.

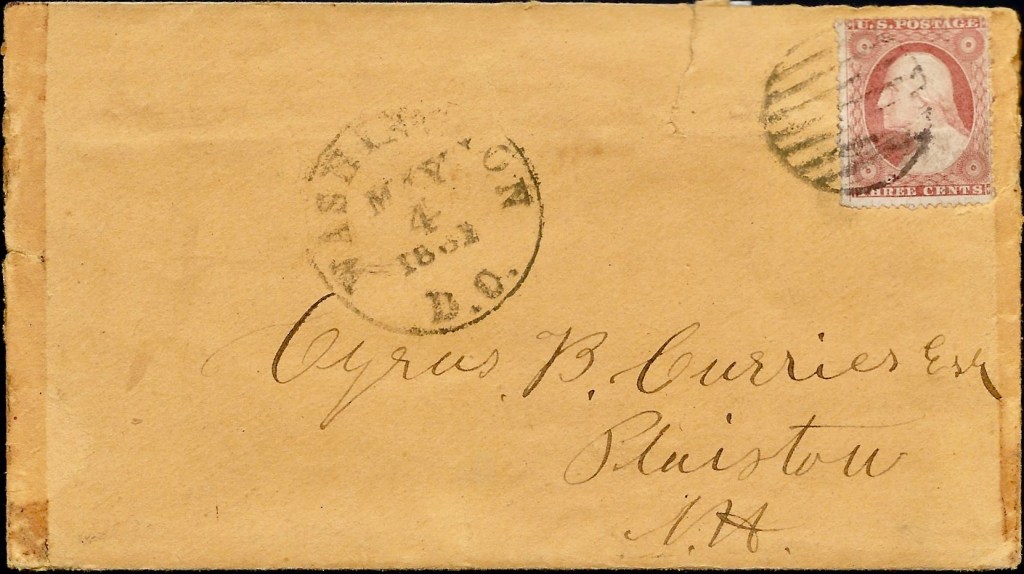

Mary wrote the letter to her cousin Annie Dunkin Adams (1834-1910), the daughter of Dr. Horatio Adams (1801-1861) and Ann Bethune Dunkin (1797-1889) of Waltham, Massachusetts. In her correspondence, Mary mentions Annie’s siblings, “Mollie”—Mary Faneuil Adams (1836-1912)—and “Faneuil”—Benjamin Faneuil Dunkin Adams (1839-1895). Annie was a pivotal force behind the Waltham training school for nurses and she devoted her life to a number of charitable causes. What’s more, Annie apparently had a friendship with the Lees of Arlington House, Robert and Mary (Custis) Lee, who are mentioned in the closing lines of this letter. How little did Mary know at the time that Mr. “Lee” would eventually emerge as the Army of the Potomac’s fiercest adversary in the turbulent years to follow.

For a good summary of the Lee’s departure, see The Lee’s Leave Arlington by the National Park Service. I note some discrepancies in the dates between that article and this letter, however.

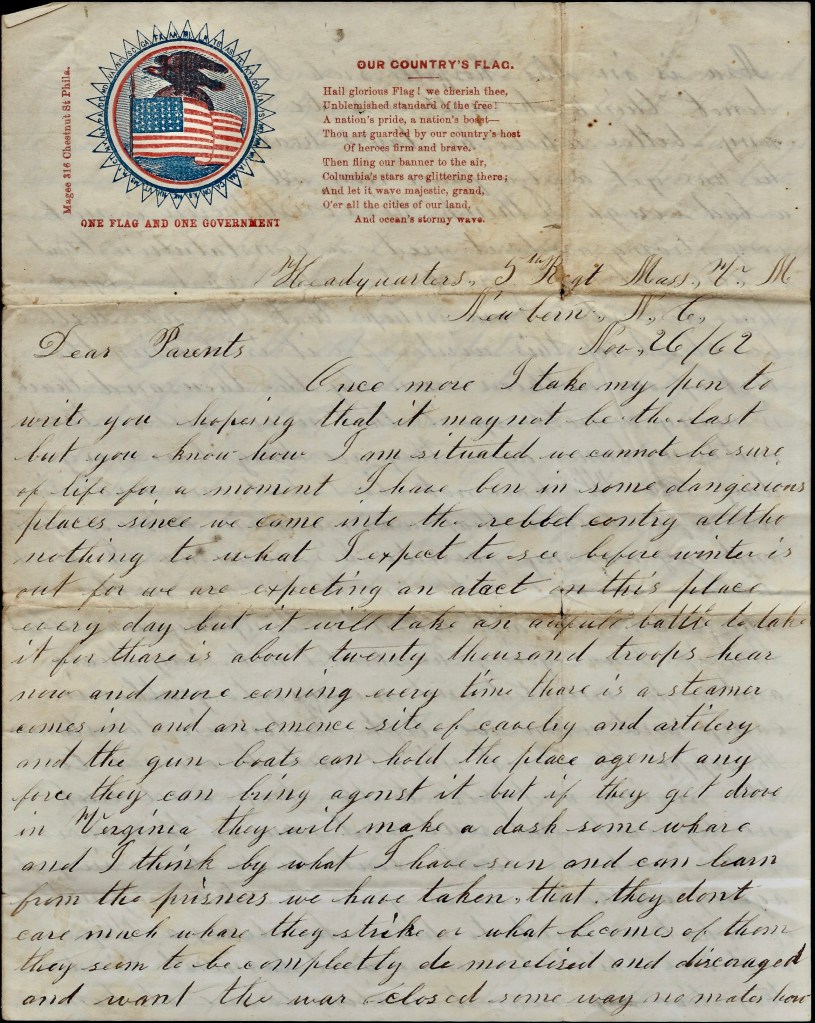

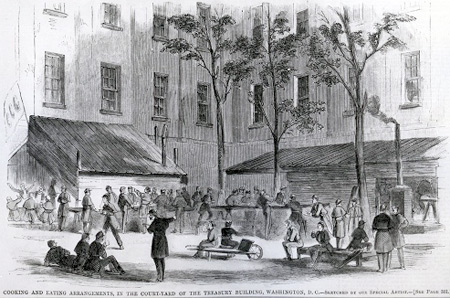

From Mary’s letter we learn that she and her mother were the individuals responsible for making the havelocks distributed to the members of Col. Samuel Lawrence’s 5th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Perhaps she made the very havelock worn by Sergeant Edward Bracket featured in the picture below.

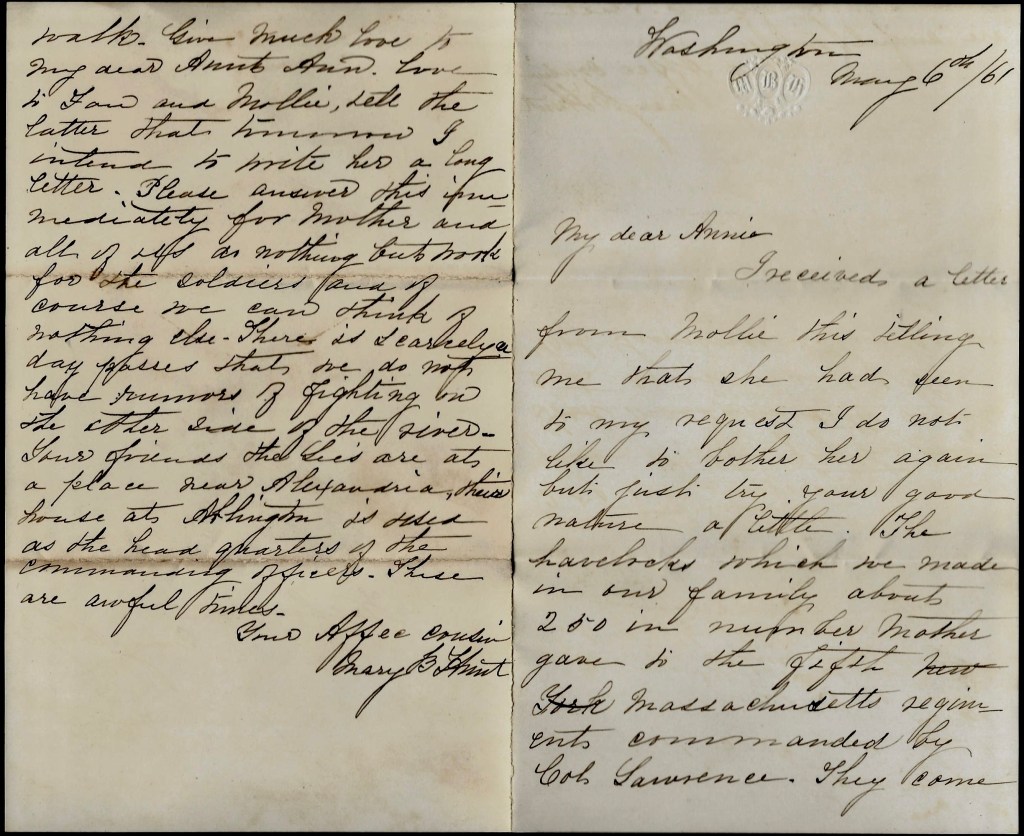

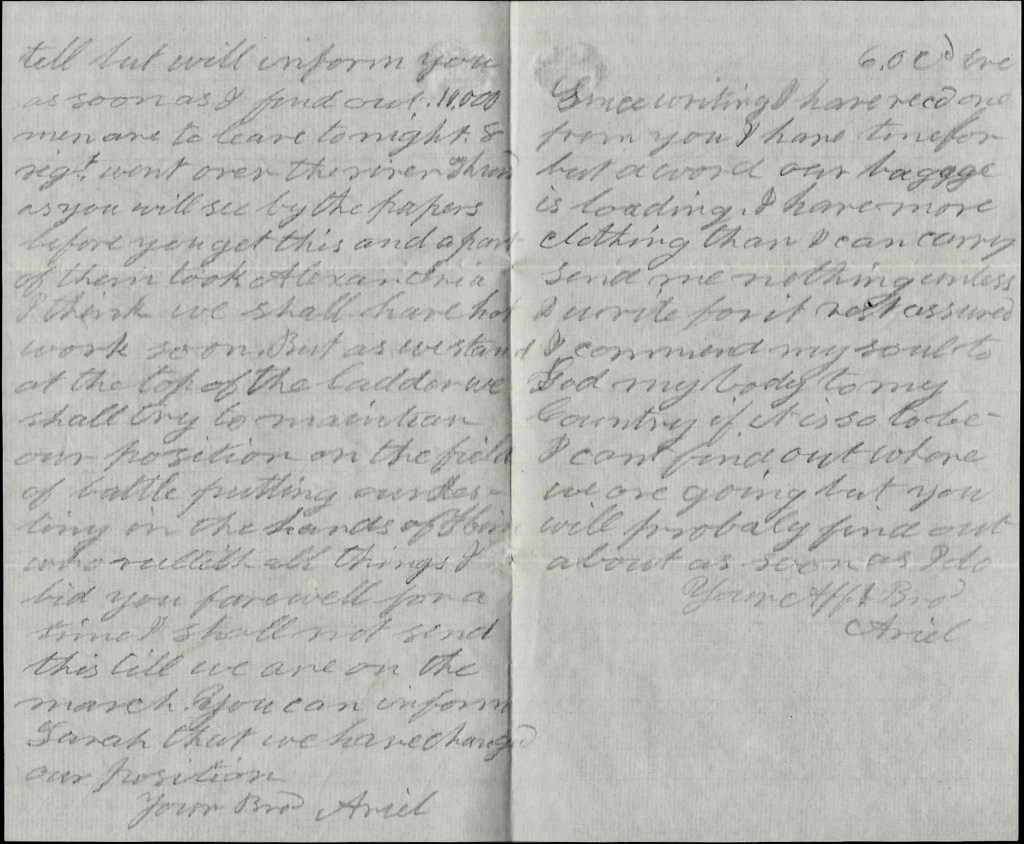

Transcription

Washington [D. C.]

May 6th 1861

My dear Annie,

I received a letter from Mollie this [morning] telling me that she had seen to my request. I do not like to bother her again but just try your good nature a little. The havelocks which we made in our family—about 250 in number—Mother gave to the Fifth Massachusetts Regiment, commanded by Col. [Samuel C.] Lawrence. They come from Charlestown and the vicinity of Boston. Mother thinks that it would be a good plan to send them enough to finish supplying that regiment as they are hard at work at Fortress Monroe. There are about a thousand in the regiment. It is much easier to have them sent from Boston to Fortress Monroe than from here. Please ask Faneuil to mention this to someone in authority for if they are sent here, it may be two weeks before they can be sent to Fortress Monroe.

I received a letter from Major Hunt this morning. It came in a round about way. I do not know exactly how it got here. Of course I was glad to get it but my anxiety is none the less for at the time he was writing, they were in hourly anticipation of an attack. He feels very confident of the success of the United States troops. However that may be, I scarcely dare think of it in any way. There is an order out for Major Hunt’s Battery to be brought to Washington. Even that seems impossible to be true.

We are all well. Presley’s foot is much better and he thinks that he will soon be able to walk. Give much love to my dear Aunt Ann. Love to Fan and Mollie. Tell the latter that tomorrow I intend to write her a long letter. Please answer this immediately for Mother as all of us do nothing but work for the soldiers and of course we can think of nothing else. There is scarcely a day passes that we do not have rumors of fighting on the other side of the river.

Your friends, the Lee’s, are at a place near Alexandria. Their house at Arlington is used as the headquarters of the commanding officers. These are awful times. Your affectionate cousin, — Mary B. Hunt