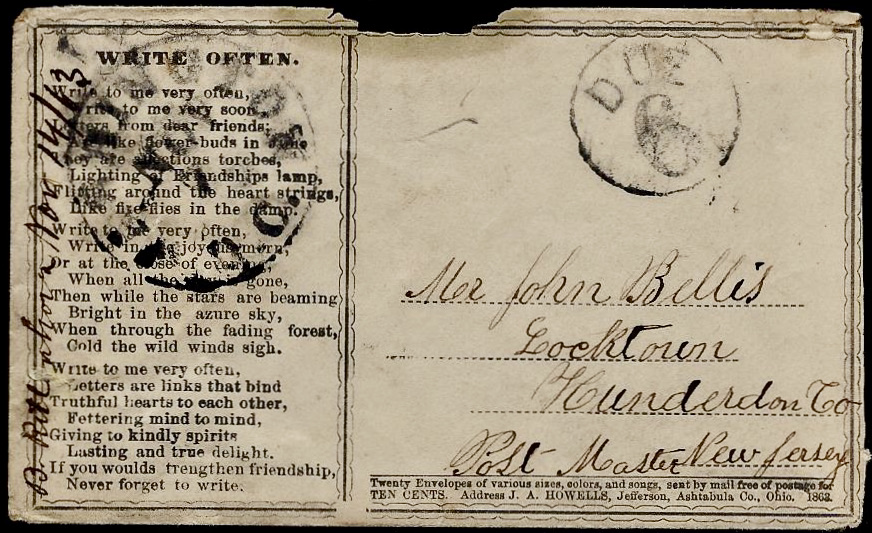

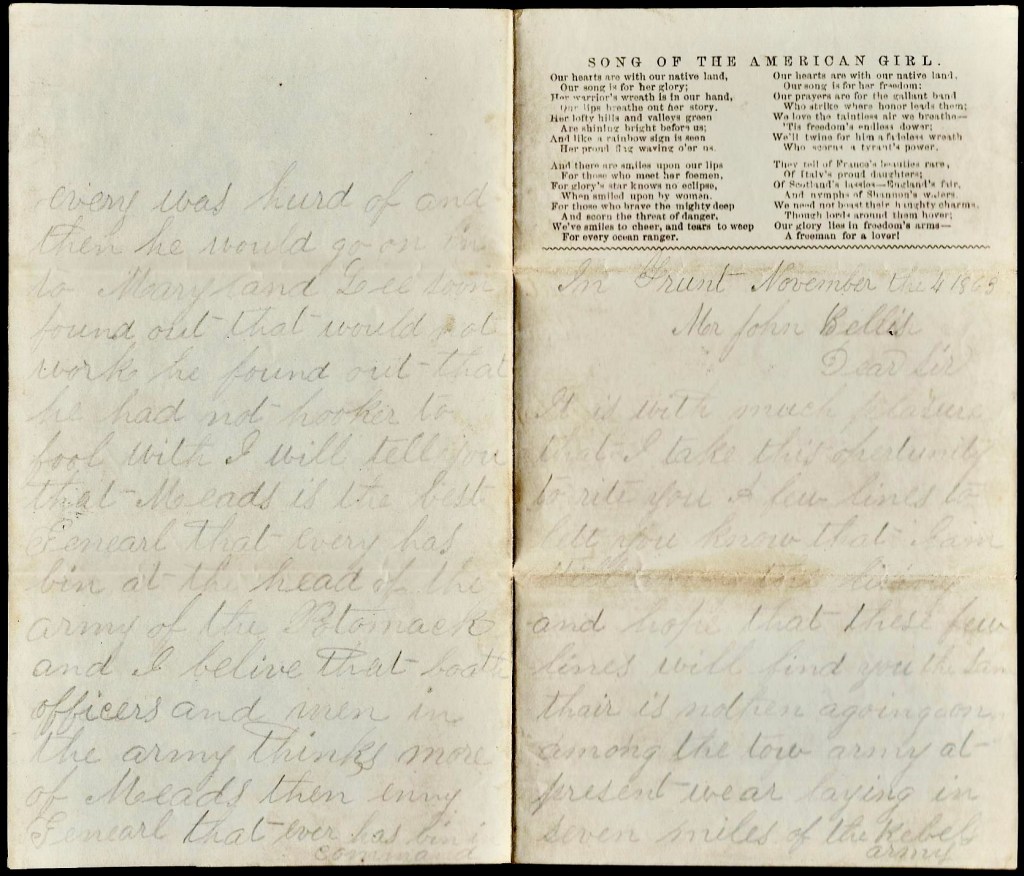

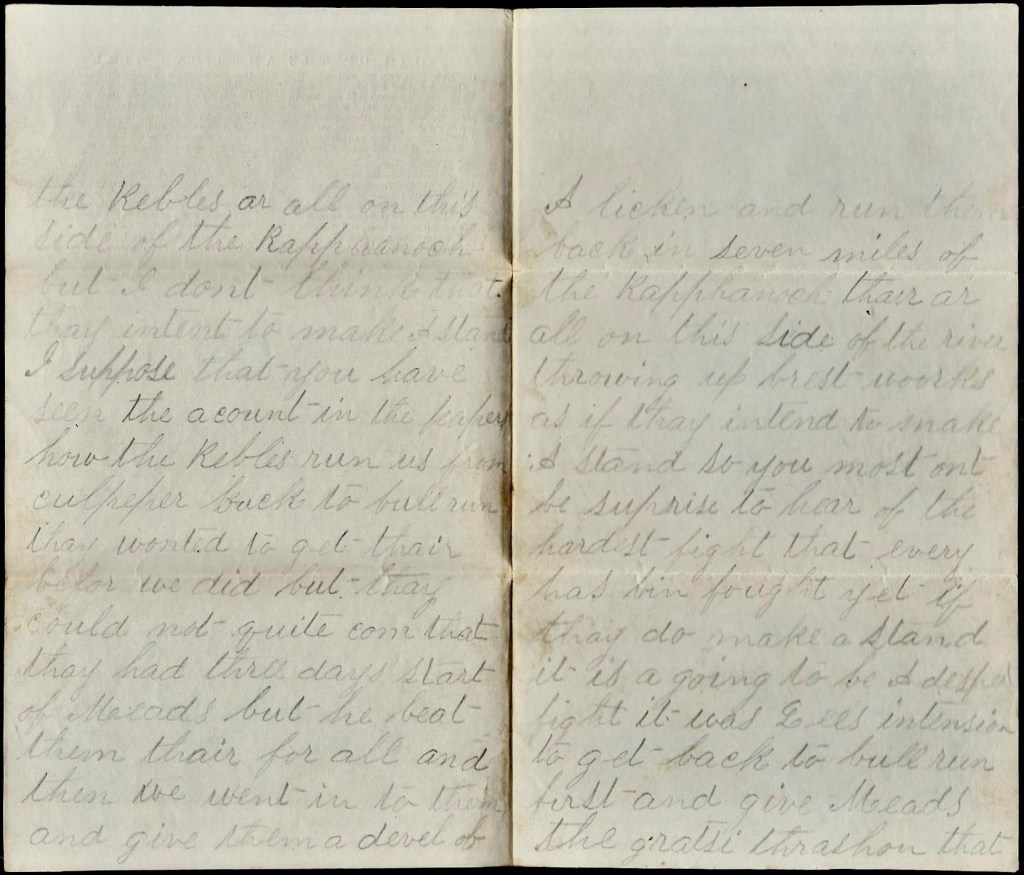

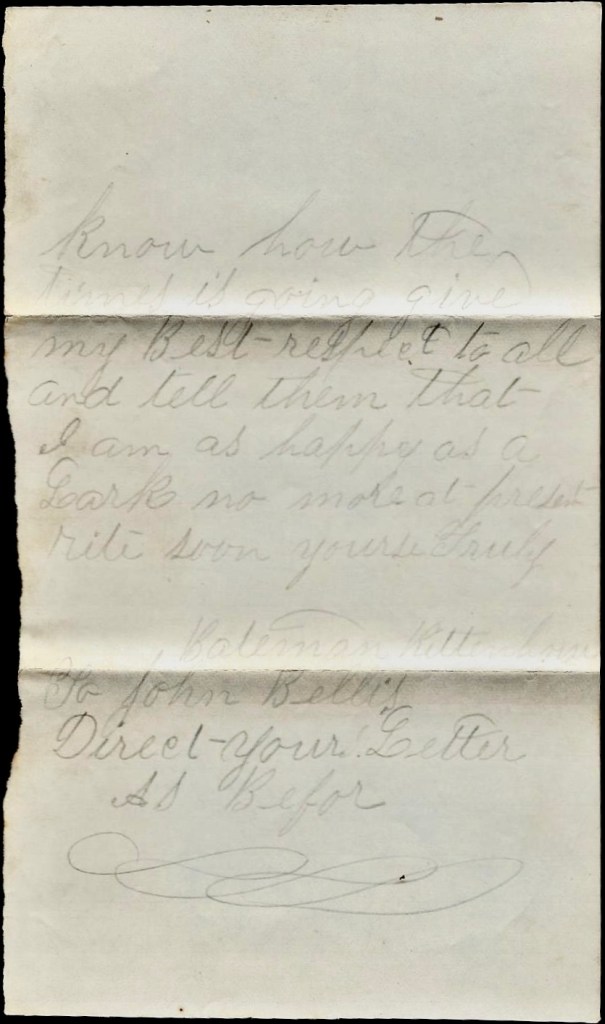

The following letter was written by William Henry Pennock (1836-1903) who mustered into Co B, 6th Maryland Infantry as a private at Baltimore on 9 June 1862. In the fall of 1863 he was promoted to ordnance sergeant and was later detached from at the Brigade Quartermaster Department. In January 1865, he was reassigned to duty as the Brigade Forage Master.

William was the son of James Pennock (1811-1848) and Matilda Mercer (1814-1880) of Chester county, Pennsylvania. He married in 1866 to Margaret Louis McVaugh (1846-1910) and in 1870 was enumerated at Mill Creek Hundred, New Castle county, Delaware, as a farmer.

William’s letter speaks of the death of “our dear brother” whom I presume also served in the 6th Maryland Infantry as several officers names from that regiment are mentioned. Unfortunately I have not been able to identify the deceased soldier, assuming that the letter is dated correctly.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Asst. Quartermaster Department

2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 6th Army Corps

January 11, 1864

My dear sister,

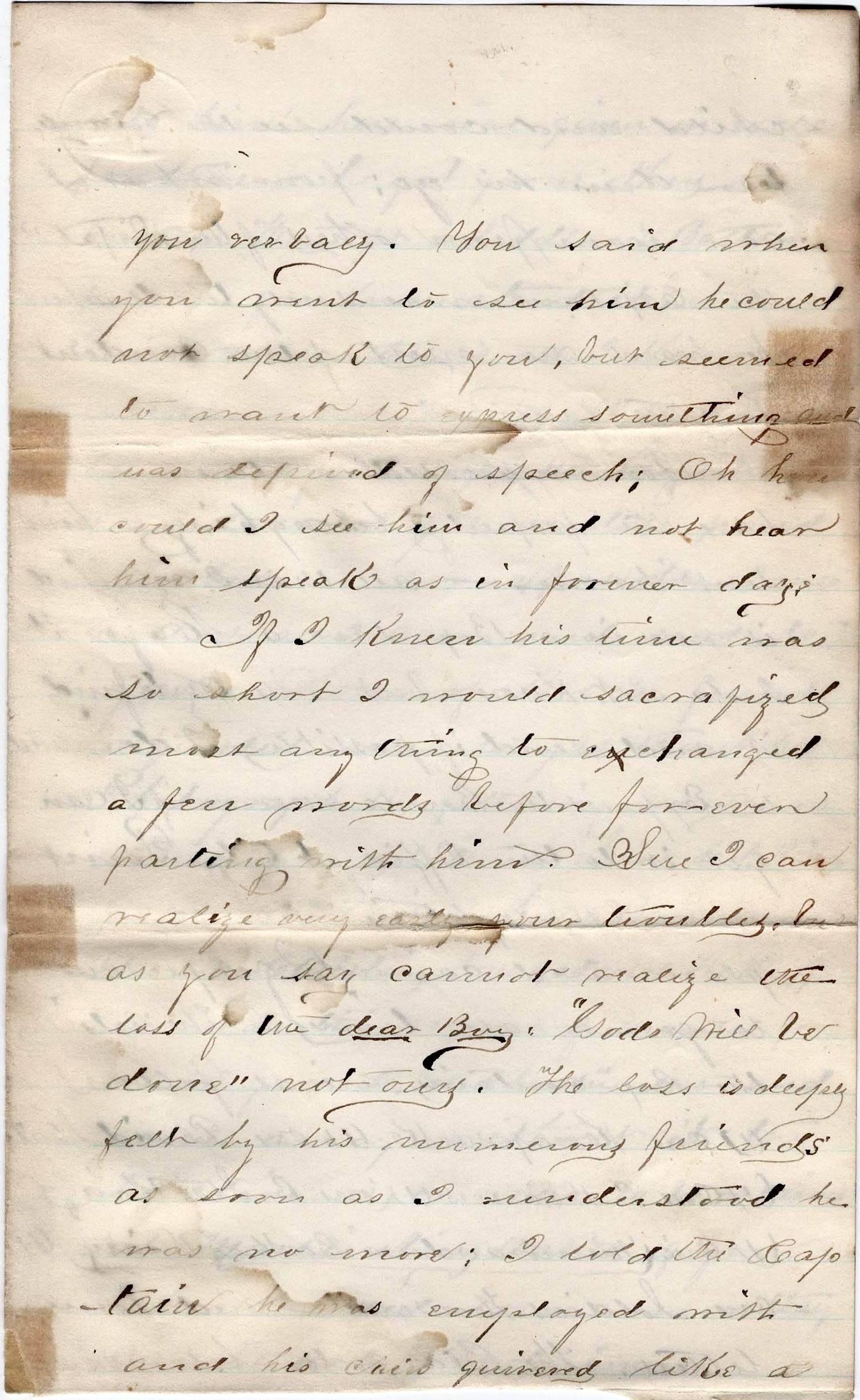

It is with a feeling of sadness intermingled with pleasure in this duty that lays before me—the first occasioned by the untimely loss of our dear brother and the latter to know “I” who is left alone is not forgotten or abandoned by you. The news of his death came to me on the 8th. An official notice was sent to the regiment and Lieutenant Col. [Joseph C.] Hill came to the office to let me know the same. Tute, I must acknowledge when I sent to see him the last time I was misinformed as to the condition of him. After I left you at the Sanitary Home to go to the boat, I stopped at the hospital to see him but was met by the nurse before I reached him saying he was better and did not want anyone to see him as rest would do him good. I did not like the only privilege denied me but for his own good, I could do no more than ask for him. I did not think after the amputation he could not survive for any great length of time and Tute, how could I tell you I thought that dear and cherished brother would leave us for a better and happier world although I thought so. And you at the same time complaining of what I was afraid might by exposure prove serious to you.

The evening before I left Washington I went to see him but met the same fate—could not get to his bedside. I then went to see the ward master in his room and the consolation was but little for what I wanted; and under circumstances existing at the time I could not come up to see you as I wanted to before I left as it was impossible for me to leave the boat on account of the office furniture being on the boat and no knowing how soon it would leave. I cannot express my feelings knowing you so near and could not see or even speakl a farewell word to those I loved.

My feelings was very much depressed after the first night on account of something you might call foolish, but will tell you verbally. You said when you went to see him he could not speak to you, but seemed to want to express something and was deprived of speech. Oh how could I see him and not hear him speak as in former days. If I knew his time was so short, I would sacrificed most anything to exchange a few words before forever parting with him. Sue, I can realize very early your troubles, but as you say cannot realize the loss of the dear boy, “Gods will be done,” not ours. The loss is deeply felt by his numerous friends. As soon as I understood he was no more. I told the Captain he was employed with and his chin quivered like a child and could see the manly tear dim his eye. From what I can learn from others of the Department, the Captain was sorely tired when he heard the news of the accident save the latter.

You expressed a desire to have the property belonging to him sent home. All that I can find is now is a box save a razor. It, I don’t know but will try to find it and send if possible. I do intend to express the box tomorrow if I can get it to the office at City Point. We are eighteen miles from the place and cannot get permission to go at all times. The articles the box contains are as follows—one knapsack, one plaid shirt, one pair drawers, one pair stockings, one memorandum book or diary, one soldier’s housewife, and some letters. The blankets belonging to him here was given in exchange for those he got from others when hurt. He kept a saddle in Baltimore. Perhaps you know about it. It is at Ferris Moore’s. This all I know of except some money that is owed to him by the boys of the regiment. If I cannot get until paid off but as soon as possible I will collect all I can and send to you.

Some of brother M. friends requested me to get them his photograph. The following names are those that wish them. Lieut. Col. Hill, Capt. Haskinson, Lieut. [James H. C.] Brewer, George M. Christie, Lieut. [Erastus S.] Narval, Thomas Duff. It was the request of Mansel for me to give G. M. Christie one and came away without it. The negative is, or was to be retained at Martinsburg, West Virginia. If you should need some more, they can be had by ordering.

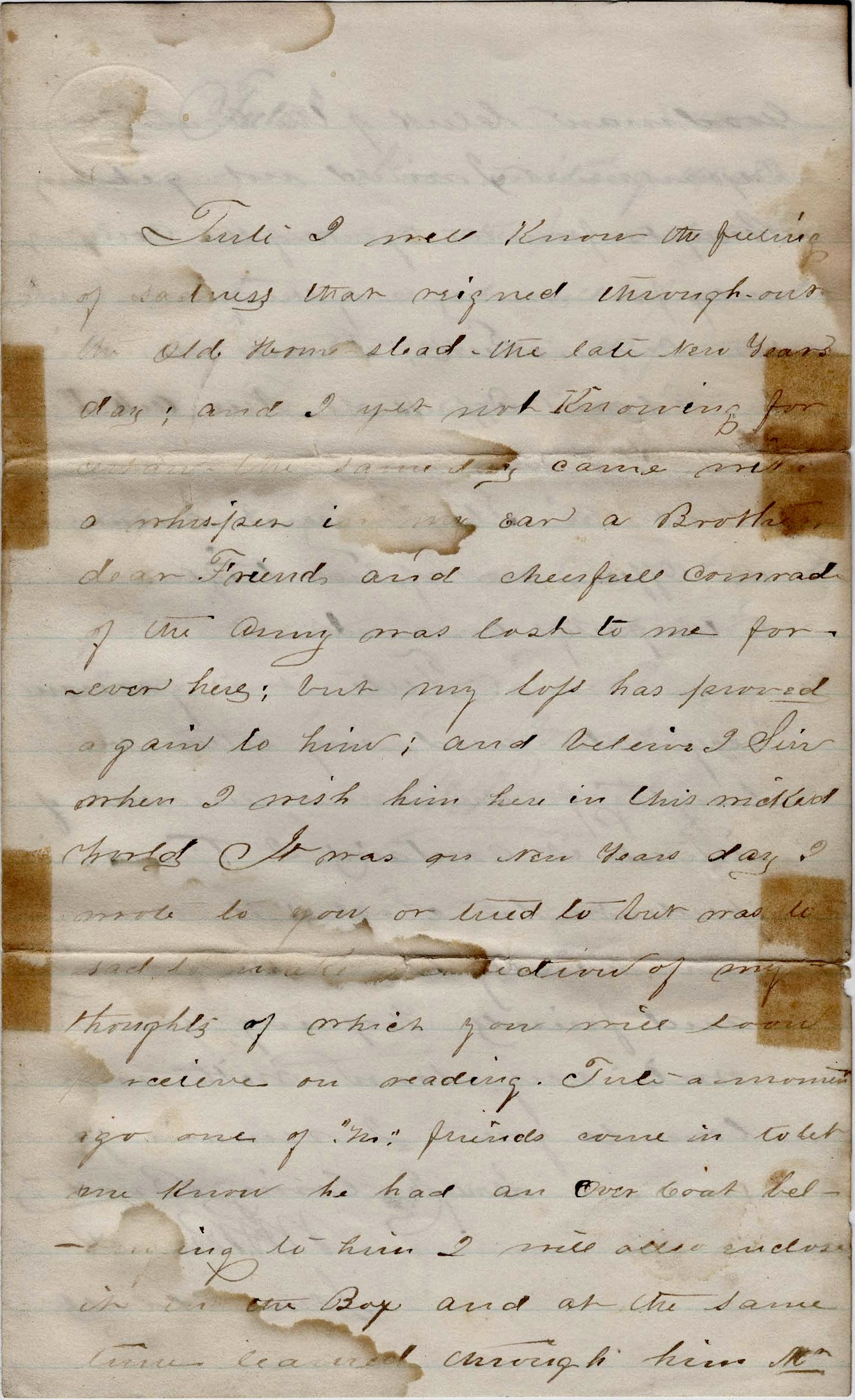

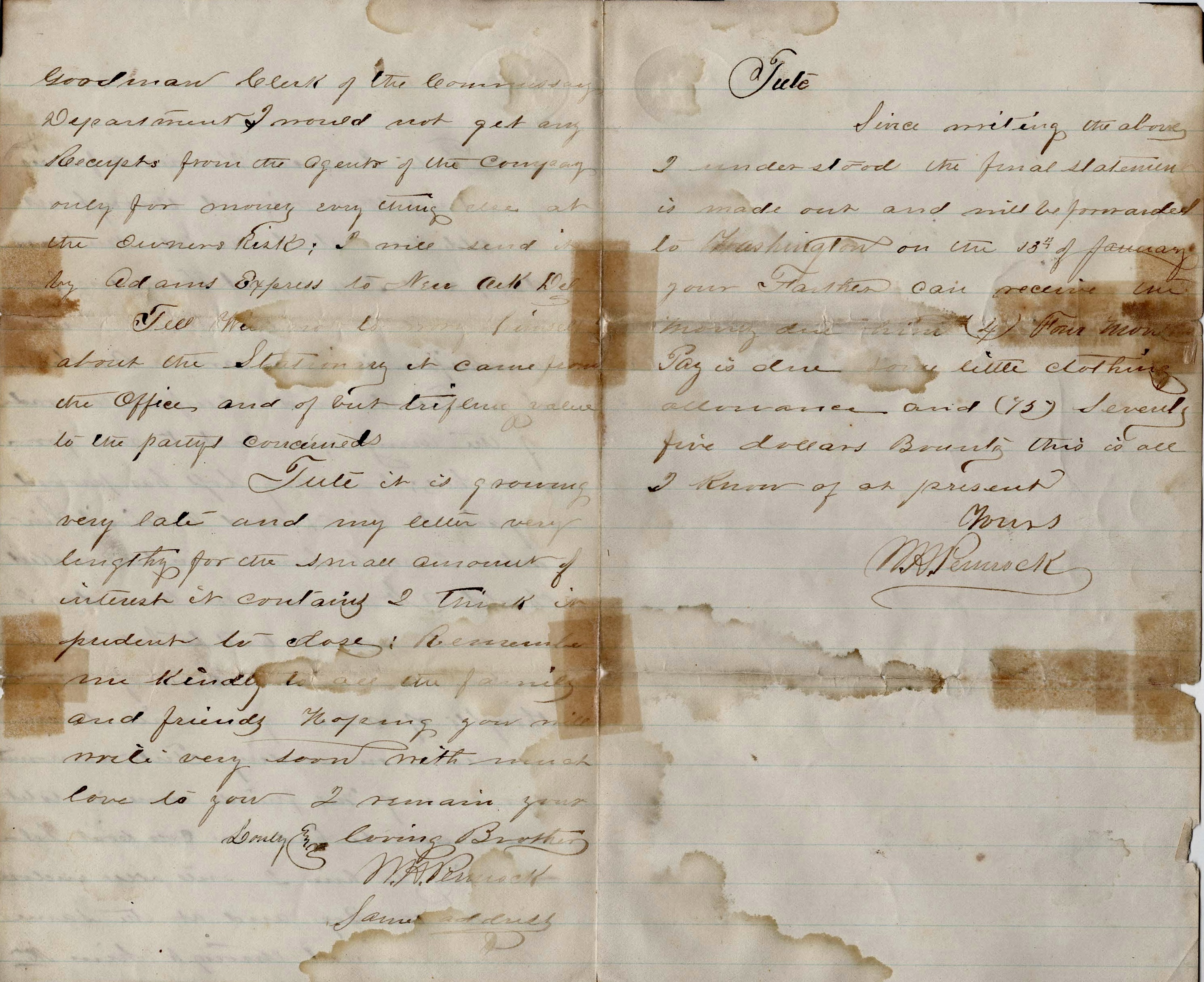

Tute, I well know the feeling of sadness that reigned throughout the old homestead the late New Years Day, and I yet not knowing for certain the same day came with a whisper in my ear a Brother, dear Friend and cheerful comrade of the army was lost me, forever here; but my loss has proved again to him; and I believe I sin when I wish him here in this wicked world. It was on New Years Day I wrote to you or tried to but was too sad to make [ ] of my thoughts of which you will soon receive on reading. Tute, a moment ago one of “no.” friends come in to let me know he had an overcoat belonging to him. I will also enclose it in the box and at the same time leaned through him Mr. Goodman, clerk of the Commissary Department, [that] I would not get any receipts from the agent of the company—only for money. Everything else at the owner’s risk. I will send it by Adams Express to Newark, Delaware.

Tell [illegible] about the stationery. It came from the office and of but trifling value to the party’s concerned. Tute, it is growing very late and my letter very lengthy for the small amount of interest it contains. I think it prudent to close. Remember me kindly to all the family and friends. Hoping you will write very soon with much love to you, I remain your lonely and loving brother, — W. H. Pennock

Tute, since writing the above, I understood the final statement is made out and will be forwarded to Washington on the 13th of January. Your Father can receive the money due him. Four months pay is due. Very little clothing allowance and 75 dollars bounty. This is all I know at present. Yours, — W. H. Pennock