The following letters were written by Alonzo D. Bump (1837-1905) of Co. K, 77th New York Infantry. Alonzo enlisted as a private in August 1862 at Saratoga Springs, New York, mustering into Co. K on 17 September 1862. At the time of his enlistment, he was described as standing 5′ 4″ tall, with brown hair and hazel eyes. He gave his occupation as “mill operator.” He was married to Mary E. Richards on 21 June 1853 at Argyle, New York.

Many of Alonzo’s letters are archived at the History Center at Brookside Museum and formed the basis for a book written by David Allen Handy in 2022. The book jacket informs us that Alonzo “lived in the thriving small cotton mill town of Victory Mills, the home of the Saratoga Victory Manufacturing Company where he was employed as a weaver. With the desire to “go down to see the world,” Alonzo left behind Mary, his wife, and his three-year-old daughter, Mattie. Private Bump’s letters were largely written to Mary, though a small few were sent to his mother, sister, mother-in-law, and his two sisters-in-law. His letters reveal a deep love shared with Mary. For Alonzo, composing letters served as the primary instrument whereby he maintained his emotional ties with Mary and had a powerful therapeutic benefit for the married couple.”

The following letters are all in private collections and it isn’t known whether they were included among the letters in the book, “Theas Few Lines.”

Letter 1

Camp near Culpeper

October 4th [1863]

Dear wife,

I now take my pen in hand to answer your kind letter that I received about 10 minutes ago and I sit right down to answer it. Well dear, I suppose that you want to know the news. Well our regiment hain’t a goin’ into cavalry for the Colonel wrote to Washington about it and they wrote back that they wanted regiments that had less than a year to stay for our regiment has got about 13 months months more to serve yet and then we shall be out of it I hope. But I think that this war will be over before our time is out for I don’t think that they can stand it a year longer. But still they may. But I think that if Old Rosecrans licks them at Chattanooga and Old Gilmore takes Charleston, that Rebeldom is about played out.

Dear, the order has just come again to move but we may not for the order may be countermanded for we have had the same orders twice before and we are here yet. Dear, I hope that you will get the money that I sent you by the time that you get this letter. But Dear, I hope that you won’t send my boots by mail for it will cost you so much for I could get a pair here for 9 dollars and if you send them by mail they will cost you most that.

Dear, you said that the girls had been over to Gailsville and there was some men a searching Mart’s house. 1 Well, dear, I hope that they won’t get Mart but if they do, they won’t shoot him for there has been an order read here through the whole army that there would be no more deserters shot but all back pay stopped from them But dear, when I was in Pennsylvania, I had all the chance to desert in world but I would not for when I come ome, I am coming home so I can stay with you in peace and not have to hide or anything else. Don’t you think that that is the best way, dear, for I know how how you would feel to have me come home and then have some man come in and take me. And I should feel bad too. But dear, I shall never desert my country and flag. But I am glad that they have got Nelse Harris. I hope that they will fetch him back.

Dear, take good care of little Mattie as you can and write often for I do too when we lay in camp, and when we are on the march, you must not expect to hear from me very often. Give my love to all the girls and here is a sweet kiss for you and one for your Mother. So goodbye for this time. From your husband, — Alonzo D. Bump

1 This is a reference to Martin (“Mart”) Davis who enlisted in August 1862 at Saratoga in Co. K, 77th New York Infantry. He deserted on 19 September 1862 at Albany, New York prior to the date of mustering in.

Letter 2

Camp on the Rapidan River

October 9 [1863]

Dear Wife,

I now sit down to answer your letter, No. 4, which I received today. It found me well and I hope that this will find you the same. I was glad to hear that little Mattie was better. I received a letter from Ell Richards the same time and I was very much disappointed to see them come and I received one from Lide and a paper the same time so you see that I had a handful of letters and I was gone when the mail come in over to the regiment to see Capt. Rockwell. He came back yesterday to settle up his business. He says that he has got his discharge and I am glad of it. He has stayed as long as I thought he would when he come away. But never mind that. I am willing to stay my time out if I can only have my health. That is all that I ask. I am willing to do my duty as a soldier.

Dear, I come out here for a soldier and I mean to be one as long as I can. I have been so far. I am on duty now most every day. Yesterday I was out with the prisoners a building rifle pits. Dear, we are down on the Rapidan now where we can see the Rebels as plain as you can see the mill from our house. But dear, we have got our quarters where the Rebs can’t hurt us. But I feel sorry for the poor boys that are out in front on picket. Dear, we had three Rebels came over last night and they said that there was lots more a coming but they have not come yet. But they may tonight.

Dear, I hope that you. will send me my boots by Express for they will come just as safe as they will by mail and it won’t cost you half as much. Dear, I was glad to hear Ell say that I need not worry about you or Mattie, I hope that when she begins to quarrel with you that she will think of me and what I have told her. Dear, have patience and not get mad too quick but think twice before you speak once. But I am a going to write to Ell just as soon as I get this done.

Dear, I think that we shall fall back from here in a few days for the Rebs have got too strong a position here for us. I think that Old Meade will fight them at Culpeper if he can get them this side of the river. We can lick them but still we may not fight at all. I hope not on the Boys account. Dear, I am a going to see the captain before he goes home and maybe I shall send you my revolver to keep for me. But then a great many times it comes in lay and it may save my life sometime if I keep it here and then if I should get taken prisoner, they would take it from me. I don’t know what I shall do with it yet. But go and see him when he comes…[rest of letter missing]

Letter 3

In Camp near Brandy Station

November 13, [1863]

Dear Sister,

I received your kind letter last night and was glad to hear from you. It found me well and in good spirits and I hope that these few lines may find you the same. We have had another bloody battle here. We made a clean sweep of the Rebs. We took all that came over the river and I wish that it had been the whole of the Reb army. But dear, we cleaned the platter once and I think that we can do it again if they will only come out and fight us on good ground. But that they won’t do for they won’t fight unless they can get into their breastworks. But we drove them out of them this time and drove them into the river.

Well, Ell, I am glad that you have got those verses that I sent to you and I hope that you will get a pretty tune for them. Ell, give my best respects to all the girls in the Mill and tell them that Old Bump is alive yet.

Ell, I received that piece that you sent to me and it is a very good advice and I thank you for that. Ell, here is a sweet kiss for you and may it not be long before I shall be at home to press them to your cheek. So goodbye for this time. This from your brother. Love to sister, Ell. — Alonzo D. Bump

Letter 4

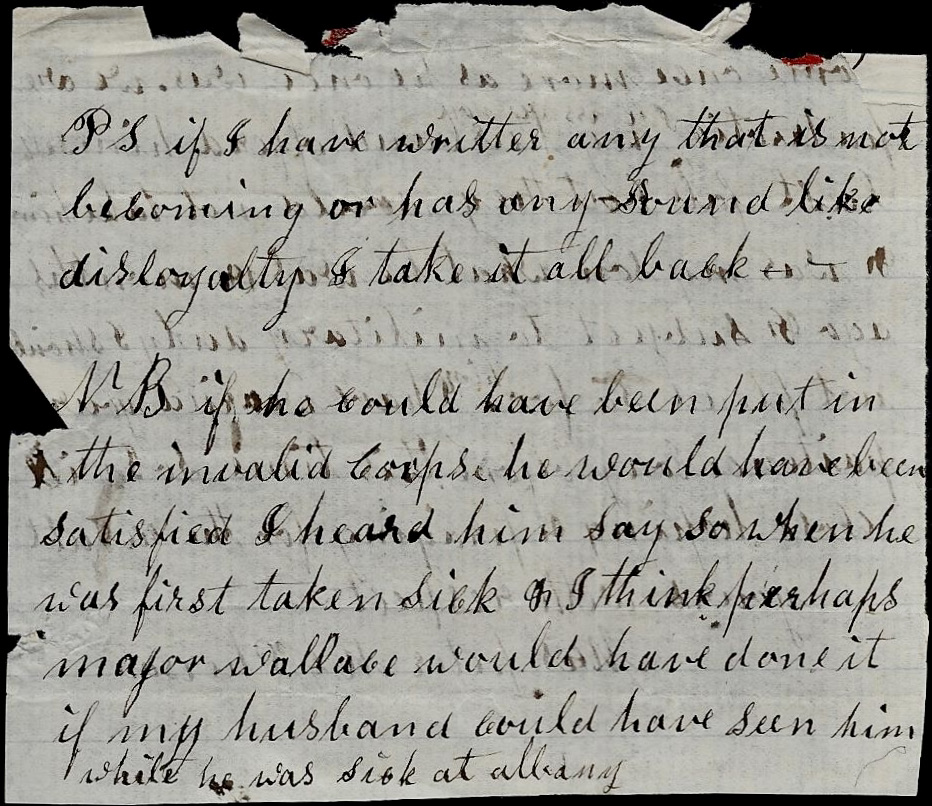

[The following letter is in the personal collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

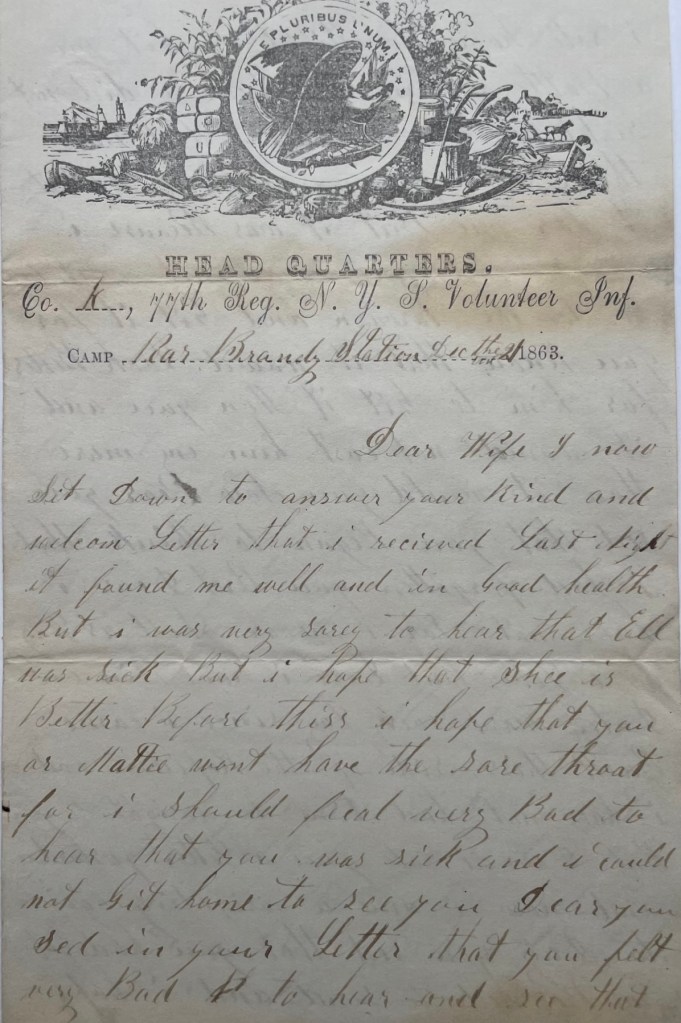

Headquarters Co. K, 77th N Y. Vol. Inf.

Camp near Brandy Station

December 21, 1863

Dear Wife,

I now sit down to answer your kind and welcome letter that I received last night. It found me well and in good health. But I was very sorry to hear that Ell was sick. But I hope that she is better before this. I hope that you or Mattie won’t have the sore throat for I should feel very bad to hear that you was sick and I could not get home to see you.

Dear, you said in your letter that you felt very bad to hear and see that I wrote home to Tipp to get me a bottle of gin but dear, I did not write to him because I did not think that you was willing to get it for me, but it was because I thought that you would not want to go to the tavern and get it for you know that it would look better for him to get it than you and it would not cost him any more than it would you. Now dear, you said that you began to think that I had forgotten you. But dear, I have not, nor I never shall as long as I live. But dear, I have been on duty most every day since I came back this side of the Rapidan and I have not had time to write to you. But dear, I wrote you a letter yesterday and now I am a writing again today.

You said that you had got my box ready to send and I hope that you have nailed it up well for they handle it rather rough when they are a coming on the cars and I hope that it will get here by Christmas or New Years. If it does, I will stuff my belly and you can bet on that.

Dear, give my love to all the girls and tell them to write to me and here is a sweet kiss for you all and I will write to you again soon. Write as often as you can and I will do the same, dear one. This from your ever true and loving husband, — Alonzo D. Bump

to Mary E. Bump

Dear, if you are sick, I want you to write to me and I will show it to the captain and maybe I can get a furlough first. So goodbye.

Letter 3

In Camp near Brandy Station

March 19th [1864]

Dear Wife,

I now sit down to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope that these few lines may find you the same. I have enough to eat and drink and a plenty of work to do and when I am to work, I feel better than I do to lay around in my tent for then I don’t have any appetite to eat and now I can eat my allowance three ties a say.

Mary, yesterday we had marching orders, come to the ready to march at short notice with three days rations, and we packed up our haversacks with soft bread and hard tack, pork, coffee, sugar, salt, pepper, and was ready and a waiting for the order to come to start. But the order was countermanded so we unpacked again and went to sleep as usual. There was a rumor around camp that Old Ewell’s Corps was on the move so we was on the lookout for him but he did not come, nor that hain’t all. I don’t think that he dare come here to fight us on our own ground for we can whip them every day in the week on fair footing. But we have never met them only once on good fair fighting and that was last fall to Rappahannock Station and there they had rifle pits dug. But they dare not stick up their heads to fire at us so we took 16 hundred prisoners there and killed a good many besides.

And at Gettysburg we coppered their goose too. If they had only stayed there one day longer, we would [have] took the whole of Old Lee’s army. But they slipped through the hole and left, and maybe it was just as well for us that they did leave for our Corps would had to went in on the Fourth of July for a celebration. But I for one am satisfied. As it was, I saved my head once from a shell or at least it came as near to me as I wanted it to.

But dear, probably I shall weary your patience by telling over old times. But I must write something to fill up my sheet so bear with it.

Dear, I received a letter from you last night and was glad to hear that you was well. I found one in it for Harry and he said that he was a going to write to Ell and he said that he would never bring her out and he thought all the more of her for doing so and I told him before I showed him the letter that if it was a going to make any trouble for my folks, that I should not let him see it and he said that it would not for Dear, I know that you all have trouble enough without my making any for you.

And Dear, tell Ell that Harry thanks her for it and says that he will do her as good a favor if he can. Dear, I feel sorry for him. I hope and pray that I shall never have any such trouble—not as long as I am in the army. And I don’t think I shall for I believe that I have got a woman that is true to me for Dear, I am you to you.

But dear, sometimes I am tempted to take a little meat for my health for I think that it would do me good. But then I don’t like the kind so I let it alone and hope that it won’t be long before I shall be at home to take my rations regular. Give my love to your mother and the girls and tell them to write to me often for I like to hear from them. I wish I had been there last night to went to the blow-out dance. I will bet I should had a good time with you and the girls and if I ever live to come home, I will have one good time, you can bet your boots and shirt.

Mary, I got a letter from mother last night stating that she had sent me a box. Bully for her. May peace go with her and Joy behind her for that, and as soon as I get it, I will write what she sent. So good night, dearest, from your ever true and loving spouse. — Alonzo D. Bump

Kiss Mattie for me Mary 50 times.

This is answer to No. 7 and 8. I suppose you have got the letter by this time that I sent by Orderly. Probably he put it in the office to Troy or Albany. He is home on a 10 days furlough. He lives to Sarasota Springs.