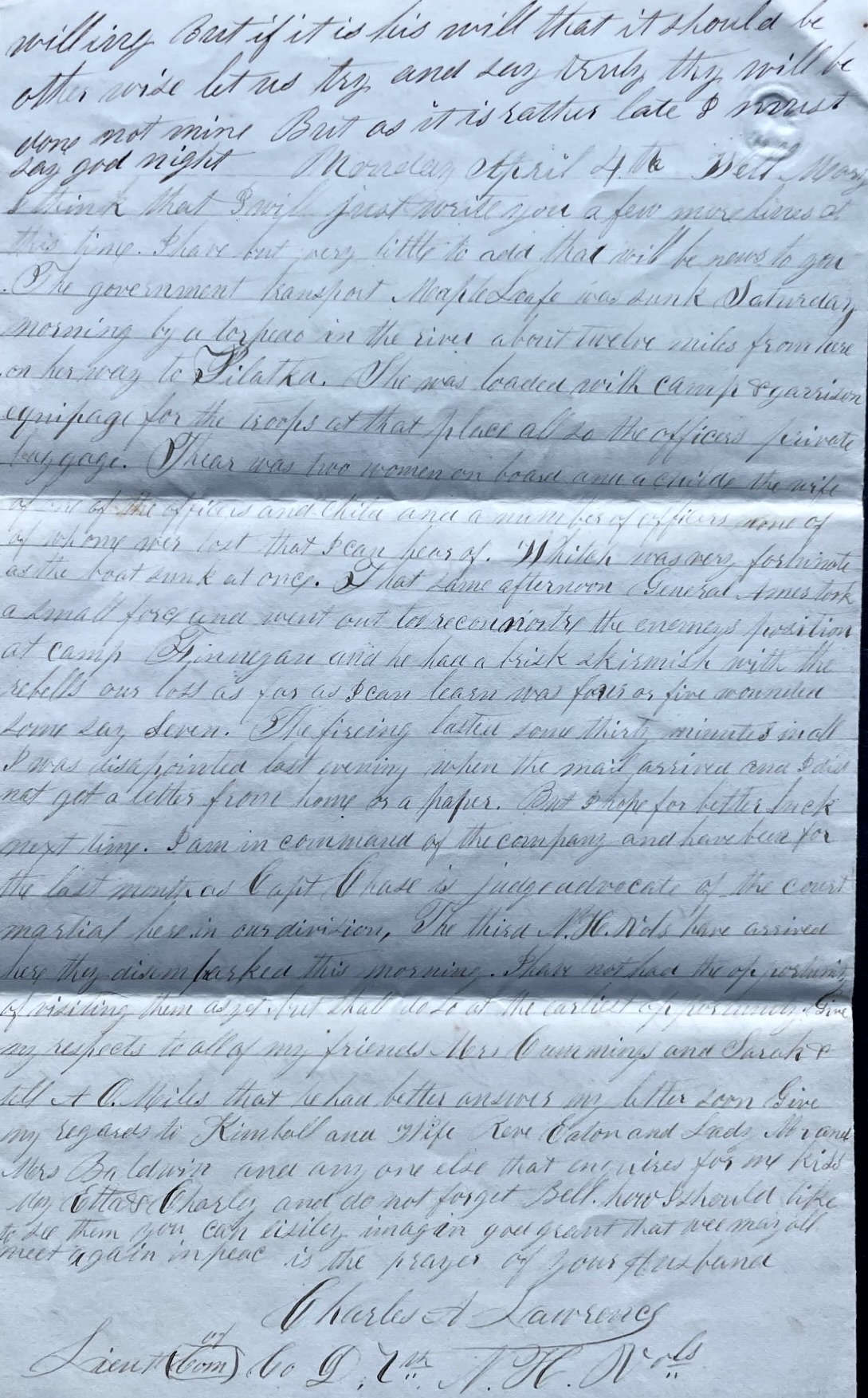

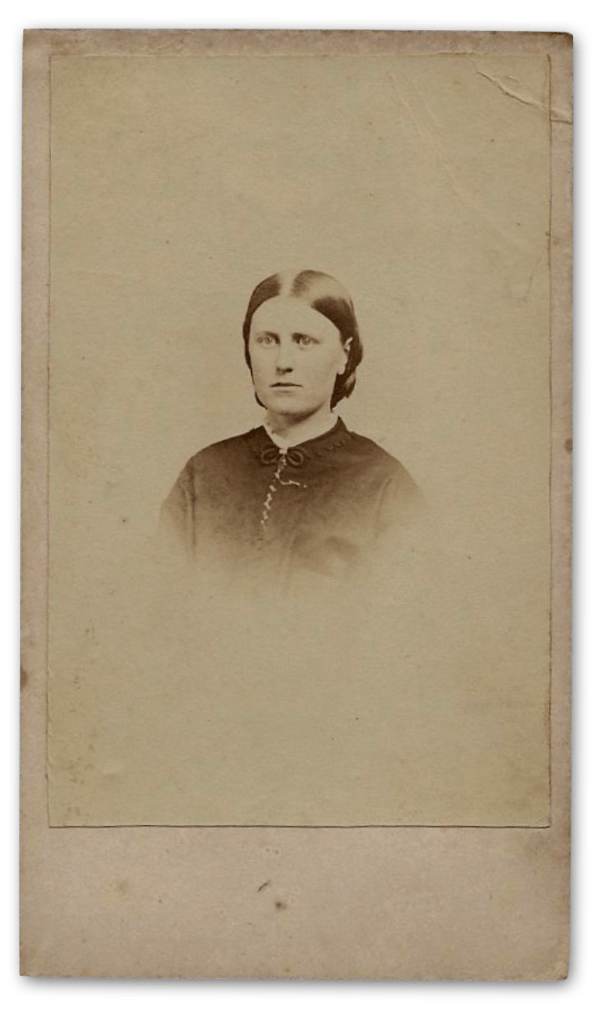

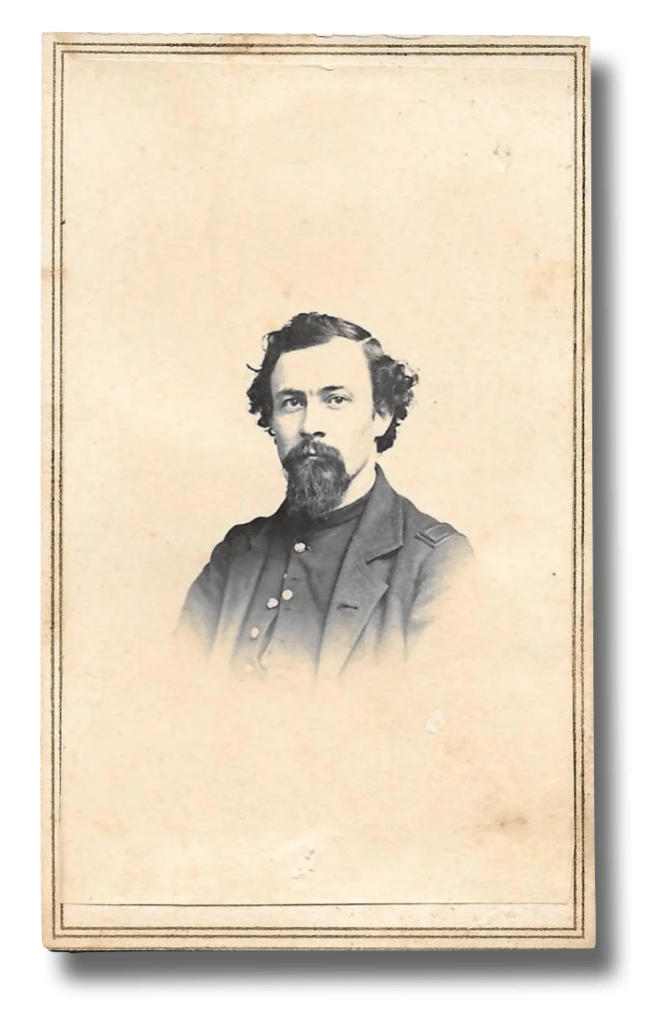

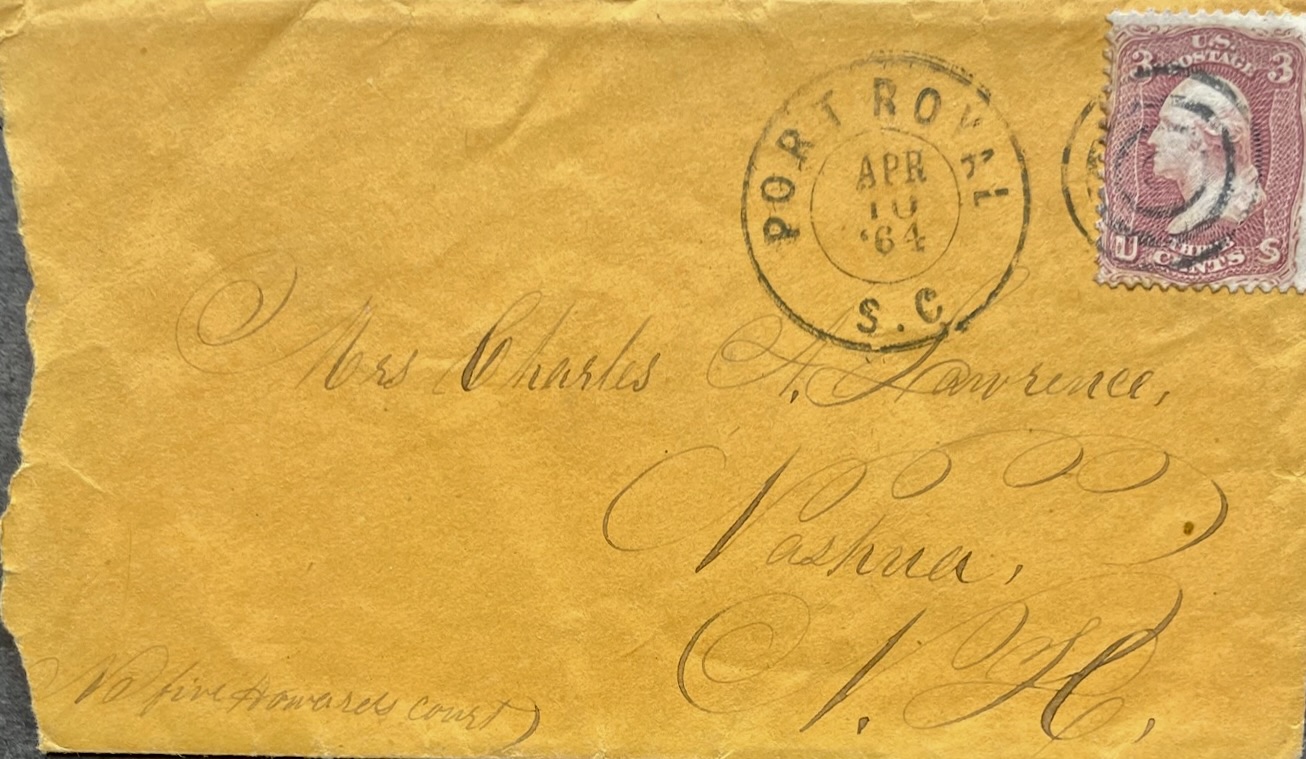

Charles Austin Lawrence (1828-1894) was 33 years old, a husband and the father of three children, when he left his home in Nashua, New Hampshire to enlist as a sergeant in Co. B, 7th New Hampshire Infantry in late September 1861. In July 1863, following the Battle of Fort Wagner where he was wounded, he was transferred to Co. D and commissioned a Lieutenant. He was wounded twice more—on June 18, 1864 at Bermuda Hundred, Virginia and on September 15, 1864 at Petersburg, Virginia—before mustering out with his regiment at Goldsboro, North Carolina in 20 July 1865.

Charles was the son of Nicholas Lawrence (1802-1877) and Olive Moors (1809-1861) of Hillsborough, New Hampshire. He was married in 1852 to Mary Farwell Patterson (1834-1914) and his children included, Marietta (“Etta”) Perkins Lawrence (1853-1924), Charles Edward Lawrence (1857-1930) and Clara Belle Lawrence (b. 1860). Prior to the Civil War, Charles worked as a “bedstead maker.” After the war he worked as “Photographic Artist” in Nashua.

[Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

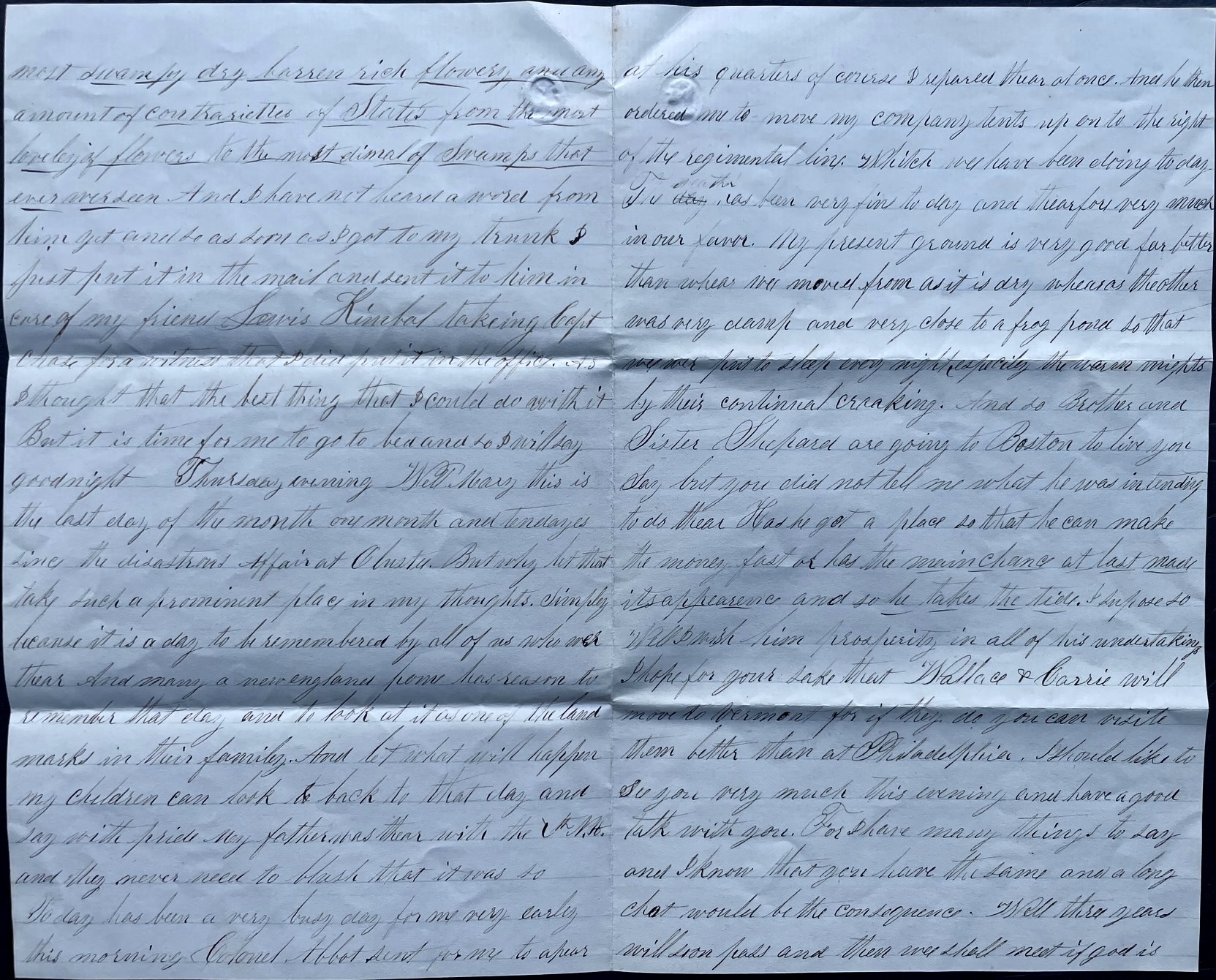

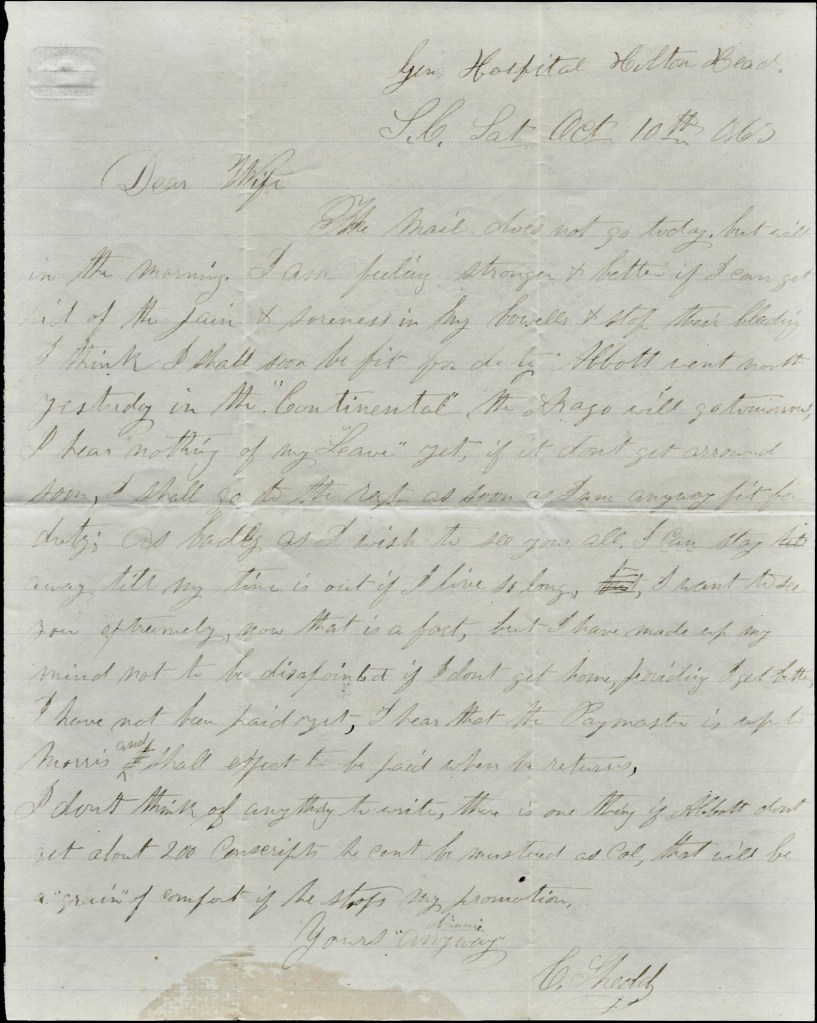

Camp near Jacksonville, Florida

Wednesday, March 30th 1864

My dear Mary,

I am sitting this evening in my tent without any other employment and therefore idle and so I thought that I would write you a few lines or at the least that I would begin a letter to you for you know that Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do. I do not like to have my hands get into any of that sort of stuff. But what shall I write about. I do not know. Everything has a sameness that I do not like to write. But then here goes.

To begin with, you say that Mrs. Cobb does not get any letters from him. He told me today that he had written three or four to her since the fight at Olustee and that was the 20th day of February and one of them has his miniature in it.

Now as to that watch that was sent by Mr. Griffin to Gordon, at that time that you first mentioned it, it was in my trunk and I was away in the wilds of the most swampy, dry, barren, rich, flowery and any amount of contraiettes of states from the most loveliest flowers to the most dismal of swamps that ever were seen. And I have not heard a word from him yet. And so as soon as I got to my trunk, I just put it in the mail and sent it to him in care of my friend, Lewis Kimbal, taking Capt. Chase for a witness that I did out it in the office as I thought that the best thing that I could do with it.

But it is time for me to go to bed and so I will say goodnight.

Thursday evening. Well, Mary, this is the last day of the month, one month and ten days since the disastrous affair at Olustee. But why let that take such a prominent place in my thoughts? Simply because it is a day to be remembered by all of us who were there. And many a New England home has reason to remember that day and to look at it as one of the landmarks in their family. And let what will happen, my children can look back to that day and say with pride, my father was there with the 7th New Hampshire and they never need to blush that it was so.

Today has been a very busy day for me. Very early this morning, Colonel Abbott sent for me to appear at his quarters. Of course I reported there at once and he then ordered me to move my company tents up onto the right of the regimental line which we have been doing today. The weather has been very fine today and therefore very much in our favor. My present ground is very good—far better than where we moved from as it is dry whereas the other was very damp and very close to a frog pond so that we were put to sleep every night, especially the warm nights, by their continual croaking.

And so brother and sister Shepard are going to Boston to live you say. But you did not tell me what he was intending to do there. Has he got a place so that he can make money fast, or has the main chance at last made its appearance and so he takes the tide? I suppose so. Well, I wish him prosperity in all of his undertaking. I hope for your sake that Wallace and Carrie will move to Vermont for if they do, you can visit them better than at Philadelphia.

I should like to see you very much this evening and have a good talk with you for I have many things to say and I know that you have the same and a long chat would be the consequence. Well, three years will soon pass and then we shall meet if God is willing. But if it is His will that it should be otherwise, let us try and say truly thy will be done, not mine. But as it is rather late, I must say good night.

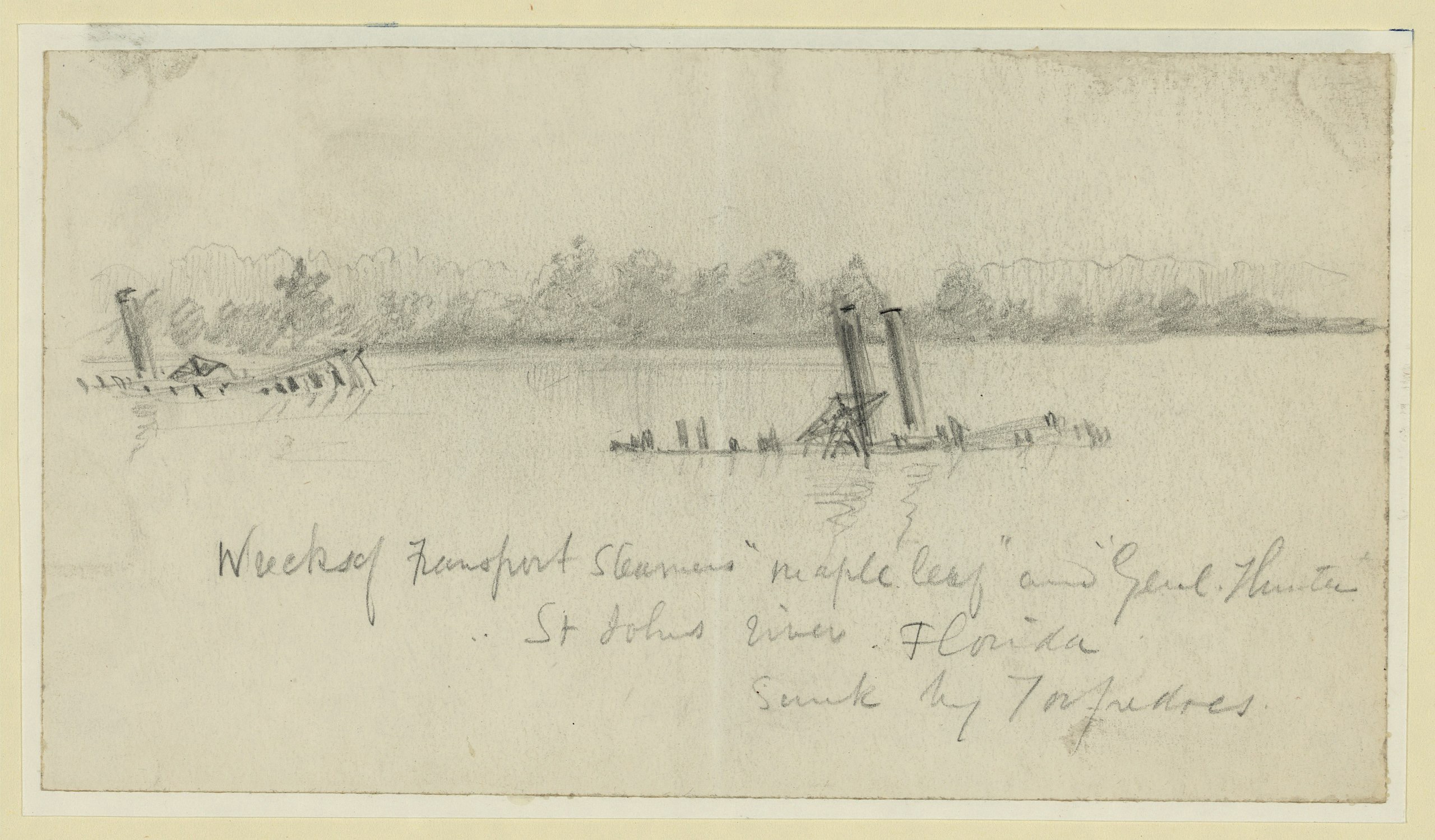

Monday, April 4th. Well, Mary, I think that I will just write you a few lines at this time. I have but very little to add that will be news to you. The government transport, Maple Leaf, was sunk Saturday morning by a torpedo in the river about twelve miles from here on her way to Pilatka. She was loaded with camp & garrison equipage for the troops at that place; also the officer’s private baggage. There was two women on board and a child—the wife of one of the officers and child and a number of officers, none of whom were lost that I can hear of which was very fortunate as the boat sunk at once. 1

That same afternoon, General Ames took a small force and went out to reconnoiter the enemy’s position at camp Finnegan and he had a brisk skirmish with the rebels. Our loss as far as I can learn was four or five wounded, some say seven. The firing lasted some 30 minutes in all.

I was disappointed last evening when the mail arrived and i did not get a letter from home or a paper. But I hope for better luck next time. I am in command of the company and have been for the last month as Capt. Chase is judge advocate of the court martial here in our division. The 3rd New York Vols. have arrived here. They disembarked this morning. I have not had the opportunity of visiting them as yet but shall do so at the earliest opportunity. Give my respects to all of my friends, Mrs. Cummings, and Sarah & tell A. O. Miles that he had better answer my letter soon. Give my regards to Kimball and wife, Rev. Eaton and Lady, Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin and anyone else that enquires for me. Kiss my Etta & Charley and do not forget Belle. How I should like to see them, you can easily imagine. God grant that we may all meet again in peace is the prayer of your husband, — Charles A. Lawrence, Lt. Commanding, Co. D, 7th N. H. Vols.

1 The Maple Leaf sank quickly in twenty feet of water. Fifty eight passengers and the crew climbed into three lifeboats with only the clothes on their backs and rowed off to Jacksonville, fifteen miles away. Four African-American crewmen were killed in the forecastle by the explosion, and four Confederate prisoners were left behind, perched on the hurricane deck which was above water, because there was not room for them in their life boats. The captain and some of the ship’s officers returned to the wreck later that day on a Navy gunboat to survey the damage and retrieve what little they could of their belongings. The crew of the gunboat removed the prisoners from the wreck. The next day the Rebel soldiers who had mined the river boarded the Maple Leaf and set fire to the part of it that was above water.