Edward Henry (1836-1899) was born on July 28, 1836 in Pottsville, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. He was living in his father’s household when he mustered into service as a private in Co. D, 96th Pennsylvania Infantry. He served three years, from 1861 to 1863. After the war, he worked as a carpenter in the south, married Mary Speacht (1843-1906), and fathered five children: William E., Robert C., Frank W., Caroline M., and Mary E. Henry.

“There seems to be a fatality attached to this army. We have now fought them for two years and today we find ourselves back in our old position.”

— Pvt. Edward Henry, Co. D, 96th Pennsylvania Volunteers, 17 Oct 1863

“This remarkable series of letters by a Pennsylvania private covers almost the entire period of the Civil War, every major phase of the war in the Eastern theater, and the three typical arenas of the common soldier’s experience–camp, battlefield, and hospital. Together, they reflect the changing rhythms of the war felt by the Army of the Potomac, from eagerness to disillusionment, excitement to boredom, blithe optimism to weary determination.

Edward Henry grew up in Schuylkill County, in the Allegheny coal-mining country of central Pennsylvania. On September 3, 1861, he joined the 96th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, commanded by Colonel Henry L. Cake, and was assigned to Co. D, whose Captain, John Boyle, and First Lieutenant, Zaccur Boyer, are frequently mentioned in his letters home. The regiment formed part of Slocum’s Brigade, Franklin’s Division at this time, later being incorporated into the Second Brigade, First Division, Sixth Corps. In the first week of May, the regiment joined McClellan’s ill-fated Peninsular Campaign, skirmishing with Rebel troops below West Point. Private Henry’s letter of the 13th of June reflects McClellan’s unruffled confidence as his forces settled down south of Richmond to await the arrival of Fremont and MCDowell before laying siege to the city. Fremont and McDowell, harassed by Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, never arrived, and on June 26, Lee attacked the Federals at Mechanicsville, opening the Seven Days Battles. On the 27th, the 96th Pennsylvania was heavily engaged at Gaines’ Mill, charging the Rebel batteries that menaced the left flank of the federal line; its losses were 13 killed, 59 wounded, and 14 missing when, at nightfall, it crossed to the southern shore of the Chickahominy with the rest of Porter’s battered V Corps. Captain Boyle of Co. D was among the wounded. Successive engagements at Glendale and Malvern Hill took a further toll on the 96th, bringing their combined casualties, according to Henry’s letter of July 5th, to 130 killed and wounded in four days of fighting. In these battles the regiment was armed only with the heavy Austrian-made muskets that had been issued to the men before they left Pennsylvania; only when they finally reached the Union encampment at Harrison’s Landing were they issued the lighter and more accurate Enfield rifles. Thus ended what Edward Henry was later to refer to as “the grand skedaddle from Richmond.” (letter of Nov. 2, 1862).

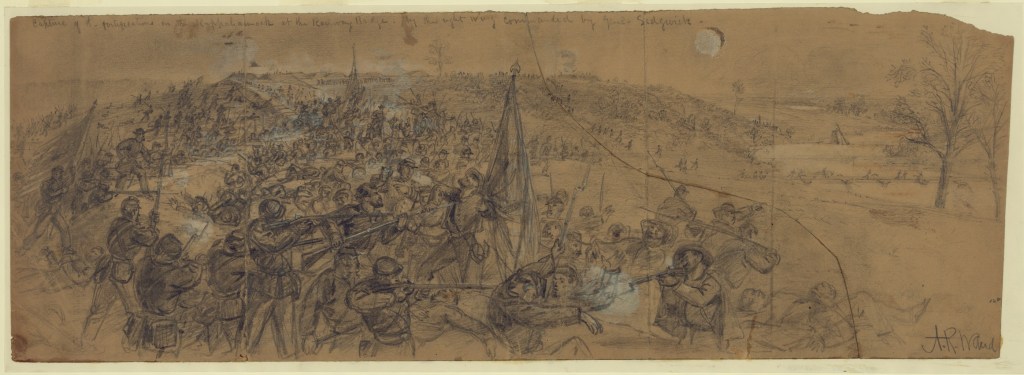

In August, the 96th Pennsylvania was transported back north to Alexandria along with most of McClellan’s troops, and on August 30th reached the vicinity of Fairfax Court House just in time to take part in the Union army’s crushing defeat at Second Bull Run at the hands of Lee and Jackson. Returning to Alexandria with Pope’s army, the regiment soon set out—under McClellan again, this time–to embark on the Maryland campaign, an attempt to repel Lee’s invasion of that state. On September 14 it took part in the Battle of South Mountain, forcing its way through stiff Rebel resistance at Crampton’s Gap, one of two approaches to Harper’s Ferry; in this action the regiment lost twenty killed, 85 wounded, out of an effective force of 400. [See “We Gave Then Hell”—Company G, 96th Pennsylvania in the Battle of South Mountain, Wynning History Blog] Three days later, the 96th helped shore up Hooker’s decimated corps in Miller’s cornfield at the horrific engagement of Antietam.

Meanwhile, at or about the time that his regiment was battling for

control of Crampton’s Gap, Private Edward Henry was sent back to a hospital near Washington, suffering from what appears to have been some form of rheumatic fever, possibly contracted in the pestilential marshes of Harrison’s Landing. On September 17th–the bloodiest single day’s fighting of the entire war, with combined Union and Confederate casualties of 27,000 men–he wrote his sister a letter from his sickbed, passing along rumors of a Union victory in Maryland. Though his report of 15,000 captured Rebels proved wildly exaggerated—McClellan claimed about 6,000—the Maryland campaign was construed as a Union victory after Lee quietly withdrew his forces back across the Potomac the following day. From the many photographs of Harewood Hospital that survive, Henry’s description (Oct. 9, 1862) can be seen to have involved no empty reassurances—the place was large, clean, airy, and offered a degree of comfort and a standard of care exactly comparable to the best civilian hospitals of the period. Volunteer nurses flocked to these permanent hospitals from all over the Union; one of these, future authoress Louisa May Alcott, spent part of her nursing career at Harewood during this period and may well have been one of the “hundred ladies” mentioned in Henry’s letter of September 9th. Under the supervision of Dr. Jonathan Letterman, the North poured tremendous energies into the construction and expansion of those hospitals; by late 1864, Washington alone boasted two dozen of them.

Such places were needed as Union casualties mounted. Though the

“coming Battle…across the Potomac” mentioned by Henry on November 2nd never occurred—much to the dismay of Lincoln, who replaced the timidly overly-cautious McClellan with Burnside on November 7th—the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13th left thousands of dead and wounded Union troops strewn thickly on the slopes below the impregnable Rebel position on Marye’s Heights. Edward Henry’s angry prayer “that we may not lose thousands of men again for nothing” (letter of Dec. 15th) echoed the bitterness and despair that gripped the Army of the Potomac in the winter of 1862-63.

The spring and early summer of 1863 found the 96th Pennsylvania—now once again including Private Edward Henry—engaged in the hardest marching and fiercest fighting of its three-year term of service, struggling its way out of an ambush on Bowling Green Road at Chancellorsville and pushing back Rebel advances on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. After that battle, it joined the rest of Sixth Corps in pursuit during the second week of July, a pursuit that involved the crossing of Cotocin Mountain at night in the middle of a thunderstorm punctuated by burst of artillery fire from the rear-guard of Lee’s retreating army. Later that month, the regiment was detached to New Baltimore for routine picket duty, leaving there in mid- September to take part in Meade’s Rapidan Campaign—a series of hard marches and skirmishes between Chantilly and the Rapidan. Henry’s letter of the 17th of October probably refers to the engagement at Bristoe Station on the 14th, in which two brigades under A. P. Hill were cut to pieces by three Union divisions under G. K. Warren, a miscalculation that earned Hill a stinging rebuke from Lee the next day, while Henry was “expecting the enemy on us any minute,” Lee was already moving his troops on a muddy march away from Chantilly, south along the railroad line to Brandy Station. The 96th finally went into camp for the winter at Aestham Creek near the banks of the Rappahannock.

The following spring the regiment would join the Wilderness Campaign under Grant, and would show its mettle at the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania. What part, if any, the rifleman-turned-carpenter Edward Henry played in that campaign is unknown. Happily, we do know that he returned to Schuylkill County with his regiment to be feted by the good citizens of Pottsville on September 26, 1864, and that, on the 21st of October, in West Philadelphia, he and his comrades were paid and officially mustered out of service.” — Patrick Leary

[Note: Pertinent excerpts from 19 of Edward Henry’s letters that were sold as an entire collection back in 1980, save the one appearing below, are included in the footnotes below. There are an additional 8 transcripts of Edward Henry’s Letters that appear on Private Voices (eHistory of University of Georgia)]

More letters from the 96th Pennsylvania published by Spared & Shared:

Mathias Edgar Richards, F&S 96th Pennsylvania (1 Letter)

John Dentzer, Co. A, 96th Pennsylvania (1 Letter)

John Madison, Co. A, 96th Pennsylvania (15 Letters)

Henry Reinhart, Co. A, 96th Pennsylvania (1 Letter)

Robert T. Rigg, Co. A, 96th Pennsylvania (2 Letters)

Zaccur P. Boyer, Co. D, 96th Pennsylvania (1 Letter)

Daniel Faust, Co. H, 96th Pennsylvania (3 Letters)

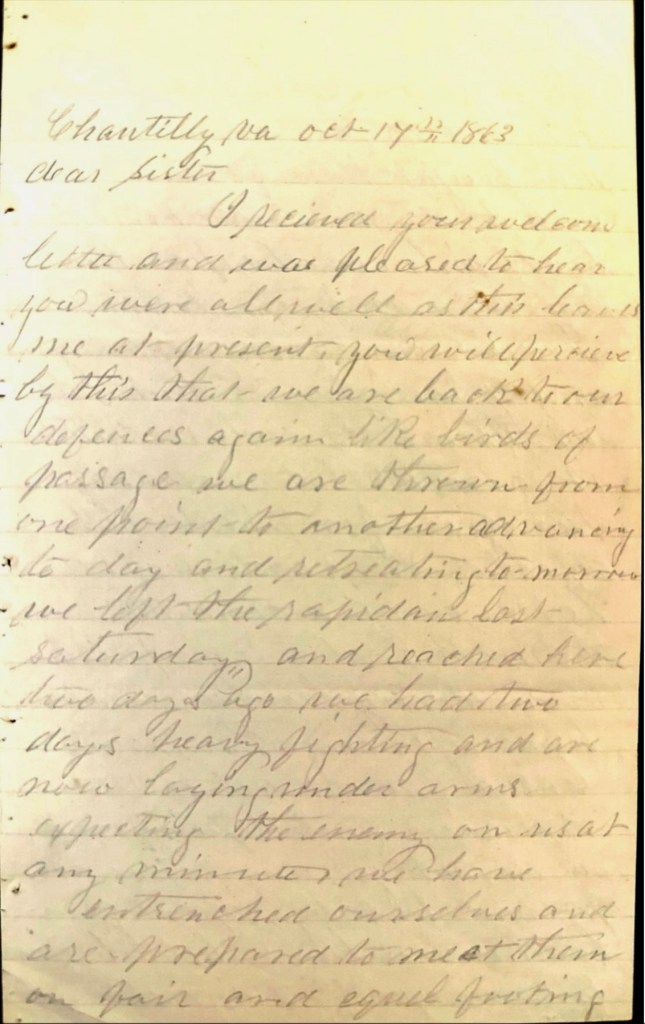

Transcription

Chantilly, Virginia

October 17th 1863

Dear Sister,

I received your welcome letter and was pleased to hear you were all well as this leaves me at present. You will perceive by this that we are back to our defenses again. Like birds of passage we are thrown from one point to another, advancing today and retreating tomorrow. We left the Rapidan last Saturday and reached here two days ago. We had two days heavy fighting and are now laying under arms expecting the enemy on us at any minute. We have entrenched ourselves and are prepared to meet them on fair and equal footing. There seems to be a fatality attached to this army. We have now fought them for two years and today we find ourselves back in our old position. There is a report that Lee is going to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania but I do not think he will undertake it at this late season of the year for should he be defeated the roads would be in such a condition as to make a retreat impossible.

Our army has been weakened by reinforcing other points and we must act on the defensive until reinforced. We do not get any papers at present but by report, Governor Curtin has been reelected by a large majority. I do not trouble myself about politics enough at present to care much who is elected but I say Andrew Curtin is and always was the soldiers friend, but I despise the party he belongs to. We here in the field have enough to do to watch the enemy on our front without dabbling in politics.

You wrote about reenlisting. I will not do so if father is opposed. I will serve my present term, if God spares my life, and if I am needed then, it will then be time enough. We have had no news from other departments and are ignorant of what is transpiring outside of our own lines.

Dear sister, I received the two dollars you sent but can make little use of them at present. The sutlers have been sent to the rear and we cannot even buy an ounce of tobacco. There is nothing I want you could send me at present until we get settled. I may then want some shirts but do not make them until I let you know. I received two letters for William but as he is in the rear, I cannot deliver them. I must close as my candle is nearly gone. I will close with my love to father, Matilda and family, Liza & family, to Lue [Lucretia] and all inquiring friends. With my love to you, I will close.

Direct as before. — Edward Henry

Lights out. Good night.

Notes—excerpts of Edward Henry’s letters