The following 1779 letter may appear to be a simple letter from a “dutiful and affectionate” son to his father, but it is actually a significant historical document that may have provided the first indication that the Revolutionary War in America might yet result in American Independence. The letter was penned by William Vernon, Jr. in Bordeaux, France, to his father (and namesake) William Vernon, Sr. in Boston, where the elder Vernon was functioning, by appointment of the Continental Congress, as president of the Continental Naval Board (precursor the Dept. of the Navy). The letter conveys the all important intelligence that Spain had joined France in a war against Great Britain which ensured that the British would have to spread their resources even thinner than before. Though Spain could not be persuaded to encourage the Americans in their quest to free themselves from the imperial control of their motherland, the alliance with France in a war against Great Britain effectively and indirectly endorsed the revolt.

Vernon, Jr, who graduated from what is now Princeton University in 1776, was sent by his father to France in 1778 (travelling with John Adams). He served for a time as an assistant there to Benjamin Franklin (with whom he continued a relationship thereafter). Vernon, Jr. stayed in France after the Revolutionary war ended until 1795 when he reluctantly returned to Newport upon his father’s threat to disown him if he did not. When passing through Bordeau on his way to Spain to negotiate matters of commerce in 1780, John Adams visited William Vernon, Jr. where he found him “in perfect health” and “that he had pursued his studies to such a purpose as to speak French very well.” [Letter from John Adams to William Vernon, 16 March 1780]

Interestingly, Vernon, Sr, both before and after the Revolutionary War was notorious in his playing a major role in the importation of African slaves into the U. S. and West Indies as part of the Triangular Trade. It is estimated that he and his brother Samuel owned as many as eight slave trafficking vessels and in the course of over 60 years, the Vernons financed well over forty slave voyages to the coast of West Africa.

[Note: This letter is from the private collection of Richard Weiner and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Transcription

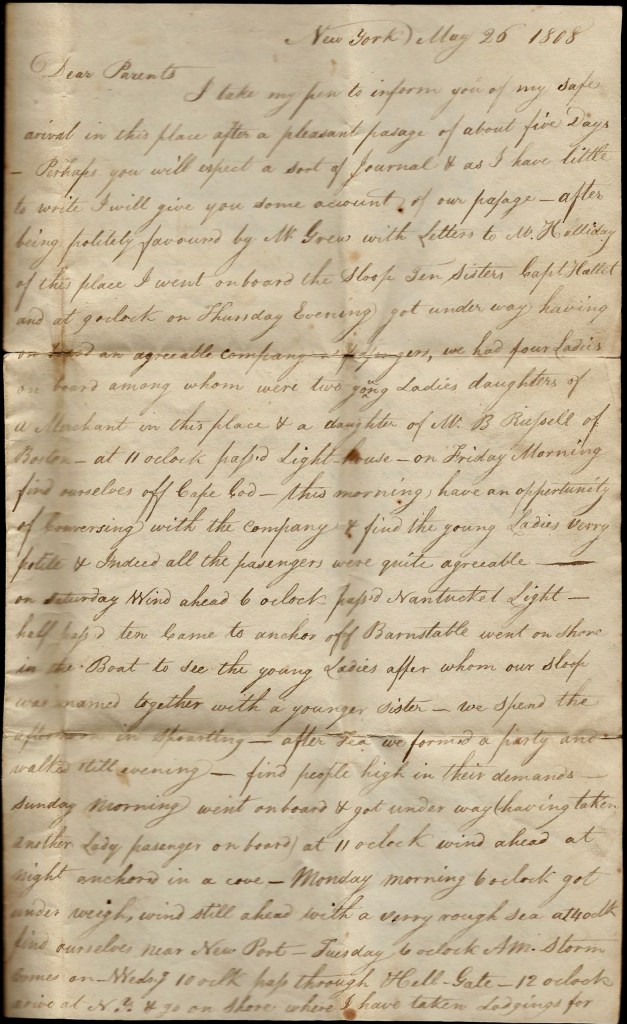

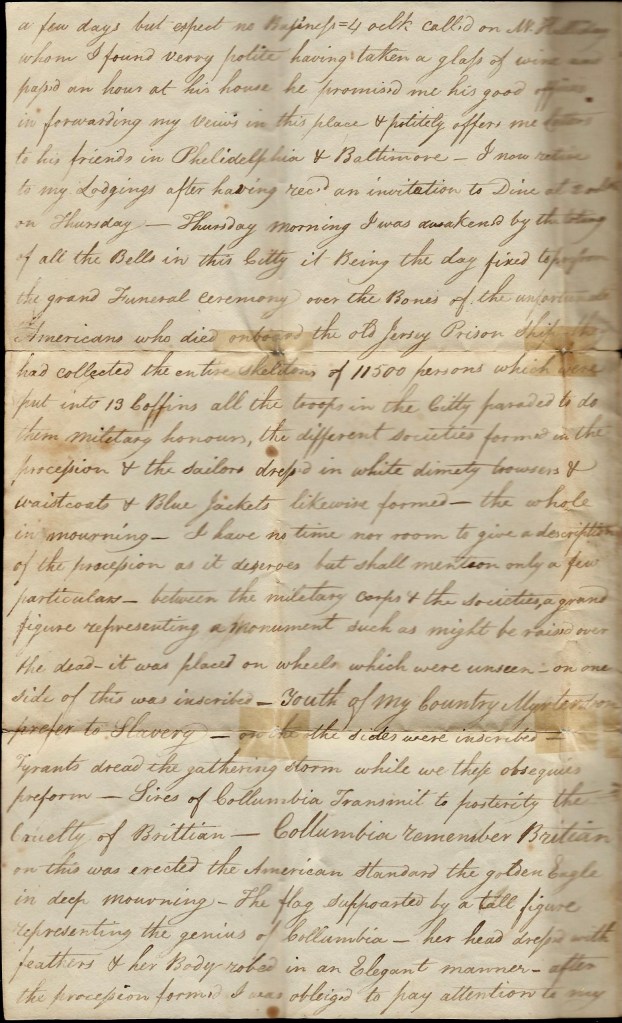

Bordeaux, [France]

July 12, 1779

Honored Sir,

The enclosed packet was intended by the Buckskin, Capt. [Aquila] Johns,1 who very unexpectedly left it upon my hands since which several events of consequence have taken place.

The Spanish Plenipotentiary at the Court of Britain gave in a Manifesto signifying his master’s displeasure at the proceedings of the British Ministry & his orders to withdraw. The 20th of June, Lord Grantham 2 withdrew from the Spanish Court & the 21st, war was declared against Great Britain. Two fleets have arrived at Brest from the West Indies consisting of upwards of 20 sail each under the convoy of three frigates. The British fleet consisting of 33 sail of the line under the command of Admiral [Thomas] Hardy has returned to port after remaining a few days in the Channel.

I have the pleasure to inform you that Mr. Bon.’d had obtained admittance for me into the House of Messrs. Freyer & Frerer; I shall enter the counting house next week. I have shipped by the General Mercer 3 a cap containing articles to the amount of 9.4.10 [ ] addressed to Mr. Hews. The captain attending and crying at every moment in my ear forces me to conclude this abruptly.

Your very dutiful and affectionate son, — W. Vernon, Jun.

1 The 200-ton Maryland Privateer Ship Buckskin was commissioned on 9 January 1779 under Commander Aquila Johns of Baltimore, Maryland. Serving aboard the Buckskin as officers were First Mate or Lieutenant John Slemaker of Baltimore, Second Lieutenant George Duck, of Baltimore, and Third Lieutenant Ambrose Bartlett, probably from Baltimore. She was listed as having a battery of twenty-eight guns and a crew of 100 men. Her owners are listed as Samuel and Robert Purviance and John Crockett and others of Baltimore. Her $10000 bond was signed by Johns and John Davidson of Annapolis, Maryland.

Buckskin prepared to sail for Bordeaux, France in early 1779. About fifteen sail of merchant vessels collected to sail with the Buckskin acting as an escort. About early February 1779 the “convoy” sailed. Buckskin proceeded on her way, but ten of the others were captured. During her passage she captured a British privateer with a crew of sixty men. Johns paroled the sixty men and forwarded the parole to Benjamin Franklin, hoping it could be used in a prisoner exchange. Buckskin arrived in Bordeaux about the beginning of March 1779. A letter from an American merchant in Bordeaux, William MacCreery, to Benjamin Franklin, one of the American Commissioners in France, sought to obtain an exception to the French tariffs on exporting salt. MacCreery noted the Buckskin twenty-two 9-pounders, had a good crew, and “she Sails remarkably fast, having been constructed for Cruizing.” He also solicited the transportation of any American government goods going to Baltimore. Franklin replied on 18 March, stating that he would investigate the matter, but also pointing out that it was improper to request favors for private parties at a time when French financial aid was so frequently requested by the American government.

In April 1779 the Buckskin was still at Bordeaux, loading a cargo for Baltimore. MacCreery, on 17 April 1779, informed Franklin that he was going to sail to Baltimore in the Buckskin, and offered to take any dispatches that the American Commissioners in France wished to send to America. Buckskin sailed from Bordeaux on 21 June 1779, bound for Baltimore. She safely arrived in Baltimore and began preparing for another voyage to Bordeaux. In late December 1779 Buckskin lay in the Patuxent River, preparing to sail. She had taken on a cargo of tobacco and was again bound for Bordeaux. On 26 December one Thomas Ridout, embarked aboard the ship. He was going to France and was entrusted with certain dispatches for Franklin. A winter freeze set in and the Buckskin was held in the river for nearly two months, finally sailing about the end of February 1780. She arrived in Bordeaux on 3 April 1780.

Buckskin (or Buckskin Hero) was on her return voyage to Baltimore, when, on 9 November 1780, she was captured by HM Frigate Iris (Captain George Dawson), off Cape Henry, Virginia. She had a cargo of dry goods, clothing, liquors and general merchandise aboard. Buckskin’s crew was stated to be 128 men, and her battery to be twenty-eight guns. She was variously listed as 400 tons and 600 tons. Other sources indicate she had thirty-six guns in her battery. Buckskin was tried and condemned in the New York Vice Admiralty court in 1780-1781. She was listed as an American merchant vessel with a “cong,” a French pass, in these papers. On 27 January 1781, the Maryland Council approved a proposal to exchange Johns, then on parole at New York. [See Buckskin, Frigate]

2 Lord Grantham was the British Minister to Spain from 1771 to 1779.

3 General Hugh Mercer was killed while leading American troops at the Battle of Princeton on 3 January 1777. A privateer named the General Mercer was launched the following year out of Massachusetts. The vessel was captured in 1780.