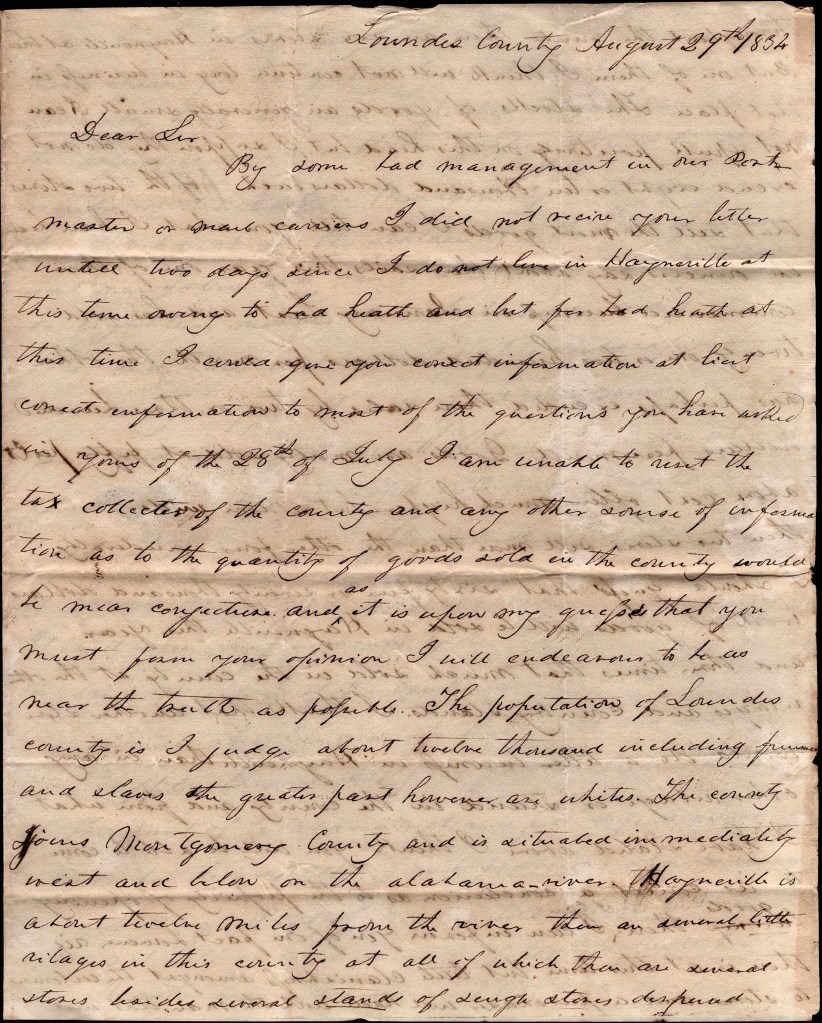

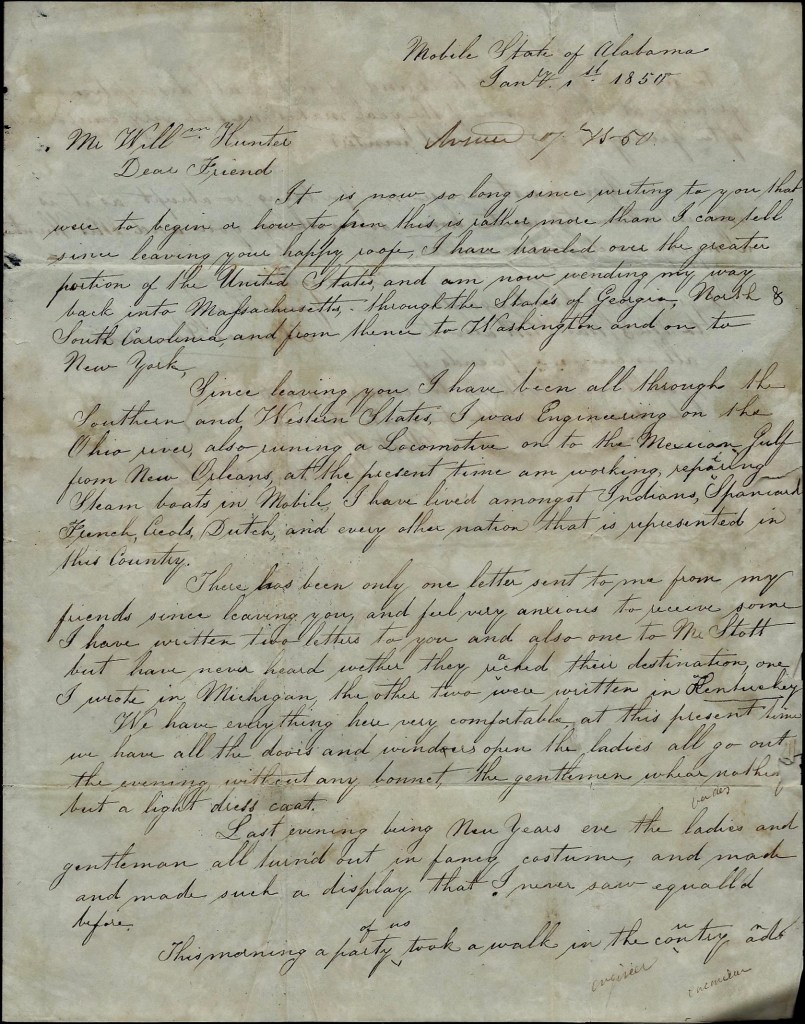

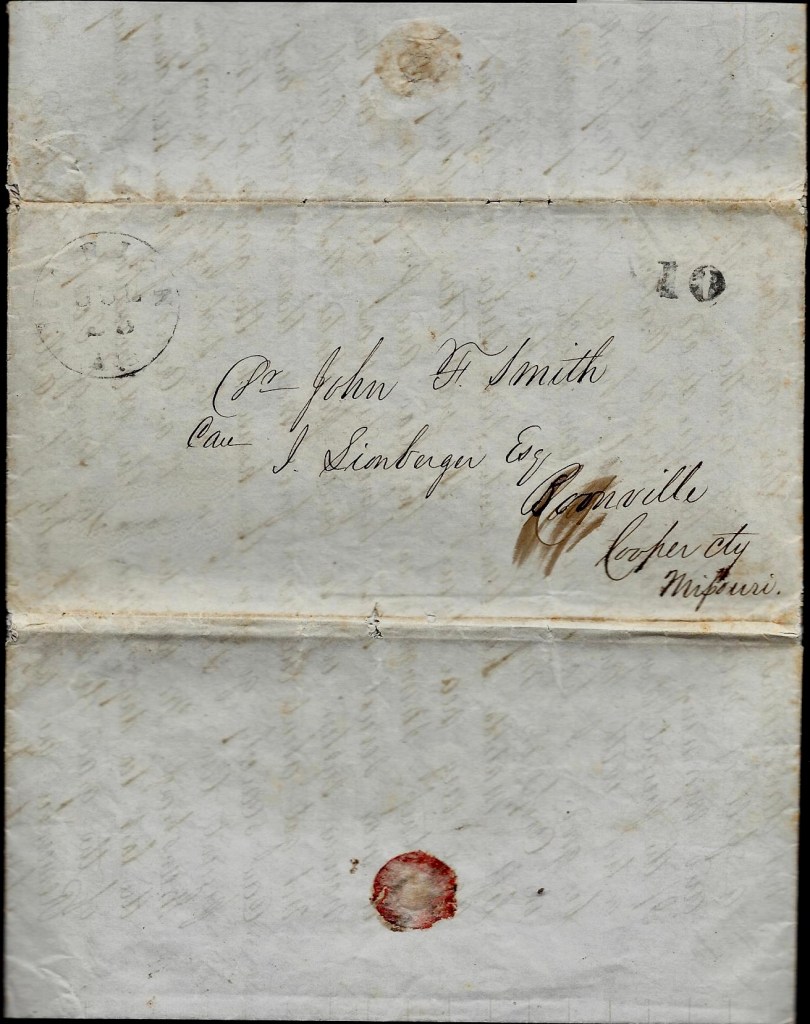

The following letter was written by John S. Sankey (Unk-1837), the son of John Thompson Sankey (1745-1819) and Ann Linton Thompson Daniel (1746-1810). He was married in Lowndes county to Patience Stephens on 27 December 1832. He was appointed Justice of the Peace in 1835 but he died on 10 May 1837 in Montgomery county, Alabama.

The letter describes the commercial business prospects for central Alabama in the mid 1830’s in response to an enquiry. Why Abijah Catlin, a prominent Litchfield, Connecticut, lawyer would have been enquiring remains a mystery.

Transcription

Lowndes County [Alabama]

August 29th, 1834

Dear Sir,

By some bad management in our post master or mail carriers, I did not receive your letter until two days since. I do not live in Hayneville at this time owing to bad health and but for bad health at this time, I could give you correct information—at least correct information to most of the questions you have asked in yours of the 28th of July. I am unable to visit the tax collector of the county, and any other source of information as to the quantity of goods sold in the county would be mere conjecture. And as it is upon my guess that you must form your opinion, I will endeavor to be as near the truth as possible.

The population of Lowndes County is, I judge, about twelve thousand including freemen and slaves. The greater part, however, are whites. The county joins Montgomery County and is situated immediately west and below on the Alabama River. Hayneville is about twelve miles from the river. There are several little villages in the county at all of which there are several stores besides several stands of single stores, dispersed throughout the county. There are six stores in Hayneville at this time, but one of them I think will not continue long in business in that place. The stocks of goods are generally small. I cannot speak positively on this head, but I suppose they do not exceed eight or ten thousand dollars each. Of the two stores that sell the most goods, I can tell you what I have heard the owners say about their sales this year. One of them commenced business in January last and has sold twenty-one or two hundred dollars per month. The other has perhaps exceeded these sales by two or three hundred dollars per month. Goods are mostly sold at fifty per cent above cost, often much higher, but seldom under. These two stores sell more than the other four individually. I should guess that sixty-five or seventy thousand dollars worth of goods will be sold in Hayneville this year, and three times that much sold in the county at the villages and country stands. I think that another store would do a better business in Hayneville than in any other village or stand in the county, and from what I have stated above, I think you will be able to come to as correct a conclusion as to the propriety of opening goods there. I can inform you of one fact, however,—viz, there is at this time but little clanishness amongst the customers to stores, and a purchaser will trade with the men that will give him the best bargain.

The Alabama river is a noble stream for navigation by steamers, but fruit is generally high. Sometimes competition brings it down until the passion is over and the combination formed by the owners. Montgomery on the Coosa river (the west branch of the Alabama) is the head of steamboat navigation and there is a little town about twelve or eighteen months old which is increasing in size and trade with almost unprecedented rapidity and many suppose it will equal Montgomery in a few years and surpass it much in time. I was once at that place and judge if proper enterprise is exerted by the people of the village for several years particularly by having good roads on the east side of the Coosa River, it will secure an immense trade to their little town. Much the largest portions of the Creek Lands (about which there has been so much row) lies nearer to that point and must get their supplies through that place from Mobile. The people of this part of Alabama, rich and poor, depend almost entirely for their clothing and provisions upon the merchants compared to that part of Georgia that you are best acquainted with. There is not half so much consumed of some products here as there. The northern and southern portions have little dealings.

The produce of the northern part of the state is carried down the Tennessee River then to New Orleans by the Mississippi. I am sorry that my situation is such at this time that I cannot give you a more exact statement in answer to several questions which might have been done if I was able to ride ten or fifteen miles. You must, however, excuse me as this is the best I can do at this time. I must stop as my paper is nearly out. I should like to hear what you conclude and when you design locating. If you should settle in another place than Hayneville, inform us.

Yours, — John S. Sankey